WHEN I REVISIT Brooklyn’s 5th Avenue, I am going back to a stretch I have traversed thousands of times. Each day between September 1971 and the fall of 1980 (the latter date gets a little fuzzy) I rode the B63 bus up and down the lengthy stretch to get to high school (Cathedral Prep in Bedford-Stuyvesant) and college (St. Francis in Brooklyn Heights) from my home in Bay Ridge, except for the days when I rode the B37 on 3rd Avenue, the more boring of the two bus routes, or used the BMT R subway.

Amazingly, never before had I actually walked 5th Avenue between Flatbush Avenue and Green-Wood Cemetery. I had seen it, but not fully experienced it. That made the lightbulb go off and the germination of a new FNY page, as I decided to present Fifth both in the sepia toned glow of lost youth and from a more objective outlook, a comparison of Fifth then and Fifth now.

It is tempting to say of Fifth Avenue that it is better now than it was. For many years Fifth Avenue was mired in poverty, even as the rest of Park Slope south of it began a slow comeback in the 1980s. Entire blocks were razed and there were empty lots, just as there were in the South Bronx of the same era. Hundred-year-old brick and brownstone housing was deteriorating. It was not until the 1990s that there was any momentum and the trickle of “urban homesteaders” who bought along 6th and 7th Avenues and the side streets in between began to invest in Fifth.

Gentrification has its benefits, but also its drawbacks. As property values and rents increase, the people who got in early are reaping great rewards. But people with incomes like your webmaster, who had earlier avoided streets like Fifth because of the former forbidding-appearing conditions, are now priced out with no hope of ever affording it, and some longstanding residents are being forced out by the changes. In microcosm it is the story of New York City itself. One extreme or the other, nothing in between.

So can you get me to say Fifth is better than it was from 1971 to 1980? The buildings have been spiffed up, there is an active local business scene (though the new ones are the cutesy, precious type that spring up when neighborhoods are first being gentrified). In the old days, people lived, worked and went to school here, not thinking they were merely scene-setters for a new group of urban professionals, and had to make way for their betters. Class envy?

The Fifth Avenue Committee is a nonprofit organization offering assistance to low-income residents who are facing higher rents.

GOOGLE MAP: Fifth Avenue in Park Slope: NORTHERN END and SOUTHERN END

Meat Me on Fifth

We are looking at Fifth Avenue’s northernmost end, at Atlantic Avenue, in 1962 (on the left) and in 1978 (on the right). Atlantic Avenue between 5th and 6th Avenues and Fort Greene Place between Atlantic Avenue and Hanson Place is the former Brooklyn meatpacking district; here, big names in the industry such as Swift and Armour packed poultry and meat products and if I’m not mistaken, there were slaughterhouses here as well. On those rare occasions when I walked to and from high school from here in the Super Seventies (about 6-7 blocks to the east on Washington Avenue) I would have to avoid huge hunks of beef swinging on meat hooks. Unfortunately during the 1970s I didn’t usually carry a camera. The platforms of the Long Island Rail Road Flatbush Avenue terminal are under the street.

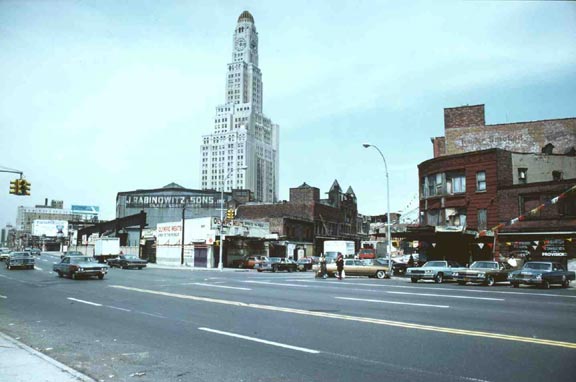

By 1980 the last of the meat houses was gone. In the picture at right, the buildings on the north side of Atlantic Avenue (one marked “J. Rabinowitz & Sons” and the railroad trestle, a last remnant of an LIRR elevated extension to the Fifth Avenue El (see below), would soon vanish and the entire block would remain empty and derelict for over twenty years. However, in 2005 it’s a different story…photos from arrts-arrchives

[2012: the top view is now dominated by Atlantic Terminal and its stores, while the bottom view is now the huge Barclays Center arena]

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Forest City Enterprises built the massive Atlantic Terminal and Atlantic Center shopping centers on eaither side of Fort Greene Place (5th Avenue’s northern extension from Atlantic Avenue). These two photos were taken in about the same place as the two at the top.

Underberg Building, 5th and Atlantic Avenues, lost to Atlantic Yards development; Barclays Center now stands on the site

photo by Doug Douglass

In the early 2000s, Atlantic Terminal and Atlantic Center builder Bruce Ratner was busy buying 23 acres of property along Atlantic Avenue from Flatbush to Vanderbilt Avenues and was poised to build residential and commercial buildings (including one that would eclipse the Williamsburg Bank tower as Brooklyn’s tallest) as well as a new arena, Barclays Center, for the Brooklyn Nets. Famed LA architect Frank Gehry was involved in the initial stages, but left the project early on.

Park Slope’s Lost El

Flatbush Avenue cuts through Park Slope grid at an angle, creating many irregular plots. Triangle Sports has occupied the only building in the triangle-shaped plot here for nearly sixty years (the actual building, though, has 4 sides). Triangle also had a Bay Ridge branch on 83rd and 5th for many years; your webmaster’s mother bought his Cub Scout uniforms there. (Above picture from Brian Merlis and Lee Rosenzweig’s Brooklyn’s Park Slope: A Photographic Retrospective)

Our principal interest in older shot, taken in 1914, is the structure in back of the Triangle building: the Fifth Avenue El. Brooklyn once had four elevated lines that did not connect with its subways except by transfer: the Fifth Avenue el, the Fulton Street el, the Myrtle Avenue el, and the Lexington Avenue el. None survived past 1969, when the Myrtle succumbed. Riding Fifth Avenue buses for over a decade, I had no idea it was once covered by an el; not till I became a subway and train enthusiast in the 1980s was I aware of this.

[2012: Triangle placed the building on sale]

The Fifth Avenue El, seen here in 1909 at 5th Avenue and 10th Street, was originally known as the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad and opened in 1889. Trains coming over the Brooklyn Bridge from Park Row would snake over el structures covering Adams Street, Myrtle and Hudson Avenues, then down Flatbush Avenue, turning onto Fifth. The el turned west for 2 blocks on 37th Street and traveled down 3rd Avenue, terminating at 65th Street; a small plaza called Stedman Square marks the terminal. Another branch turned east down 38th Street, branching into the West End el (New Utrecht Avenue) and Culver el (McDonald Avenue). The Fifth Avenue ceased operations in 1940, orphaning the Culver connection; it operated as a shuttle from 9th Avenue beginning in 1956, when the Culver el was connected to the IND tunnel ending at Church Avenue. Fifth Avenue El stops were at St. Marks Avenue, Union Street, 3rd Street, 9th Street, 16th Street, 20th Street, 25th Street, 36th Street, 40th Street, 46th Street, 52nd Street, 58th Street and 65th Street. (Above picture from Brian Merlis and Lee Rosenzweig’s Brooklyn’s Park Slope: A Photographic Retrospective)

It’s easy to say that the BMT 4th Avenue subway a block away put the Fifth Avenue El out of business. But the 4th Avenue was built in 1915-1916 by the same company that operated the Fifth Avenue, and the two lines coexisted profitably for almost a quarter century. Possibly, the Great Depression sounded the el’s death knell. Almost immediately after the el’s demise, its pillars along Third Avenue were employed to carry the roadbed of Robert Moses’ new baby, the Belt Parkway (assuring that Third Ave. would continue to be in the shadows –which would be extended all the way to Hamilton Avenue!) In the early 1960s, these el remnants would disappear as well, as the Belt in Sunset Park would be reconfigured as the Gowanus Expressway, leading to the new Verrazano Bridge. There’s a present proposal to sink the Gowanus underground in a new Big Dig. Good luck with that.

1924 BMT map showing Fifth Avenue El. The Fifth Avenue can be seen toward the bottom of the map.

Upper Fifth

O’Connor’s Bar, a Fifth-xture between Bergen and Dean since the 1930s, has a new awning, replacing an old-time calligraphic sign that had been there since the 1970s. Meanwhile, an ancient sign on the fruit and vegetable stand next door does survive.

Wendy Mitchell, in New York City’s Best Dive Bars, observes: “O’Connor’s has made the leap from hard-drinking old-man bar to hipster paradise .. now that the crowds are here, the place can become packed on weekends, but at off-times it still maintains a bit of its old man Brooklyn appeal.”

The House of Tuition, 5th Avenue south of Bergen

Storefront church. Upper 5th Avenue still has a number of these.

Restored stained glass, storefront, 5th between Bergen and St. Mark’s.

You can almost convince me on gentrification when you see great reclamation jobs like this one at 5th and Warren Street. This was one of those burnt-out hulks I used to ride past in the bad old days.

Guidebooks usually ignore the western Slope,since the Slope’s landmarked buildings cluster near the park. But here you’ll find a great mix of buildings, like this tiny two-story brick item on Baltic Street, just west of Fifth. Note that its occupants feel obliged to bar the windows.

The street was created in the 1980s when Key Food was built on 5th and new housing replaced empty lots on Baltic and Butler. This was the first shot fired in the ongoing reclamation project now so successful on Fifth.

Could the drive be named for the KC Royals’ sidearming relief pitcher in the 1980s?

No: it was named in 1988 for longtime Fifth Avenue Committee president Dorothy Quisenbury, who, as far as we know, was no relation to the late Dan Quisenberry. Where Gregory comes from…any takers?

Another reclaimed building on Fifth, this one on Sterling Place. Some streets in this area are named for Revolutionary War heroes, specifically those of the Battle of Brooklyn, fought in the vicinity in August 1776.

Pennsylvanian William Alexander (1726-1783) claimed to be a nobleman of the house of Stirling in Scotland, though the House of Lords in Britain rejected him. Despite that, or perhaps because of it, the Major General fought on the patriots’ side during the Revolution; in the battle of Brooklyn, August 27, 1776, he led a band of 250 troops from Maryland who engaged the British and Hessians, who had an overwhelming advantage in numbers, long enough to allow the bulk of the patriots to escape death or capture, though Stirling himself was caught (see Old Stone House, below).

The general is remembered by Sterling Place, which runs from Park Slope to Brownsville; the streets misspells his title.

Fifth Shift

Fifth Avenue is a demarcation line of sorts, as a number of cross streets change names here. St. Mark’s Place becomes St. Mark’s Avenue; Warren Street, Prospect Place; Baltic, Park Place; Butler, Sterling Place; Douglass, St. John’s Place; Degraw, Lincoln Place; and Sackett, Berkeley Place (though old maps show that Degraw and Sackett once extended to Brownsville, replaced by Eastern Parkway in the late 1800s.) The genesis of this ‘shift’ is conjecturable, since other streets do not change their names as they cross Fifth. Also interesting are the “Places,” which extend for miles over 3 or 4 neighborhoods (interrupted by Prospect Park). As a rule, one block streets or dead ends are called “Place.”

Fifth between Sterling Place and St. Johns Place featured Brooklyn’s best-known rock club in the early to mid 2000s outside Williamsburg and Greenpoint, Southpaw; despite the name, it’s on the right (east) side of the street. By 2005 the venue had presented both rock acts like Sleater-Kinney, Morningwood and the Go-Betweens as well as hip hoppers Big Daddy Kane and Slick Rick.

[Southpaw closed in early 2012]

A hint of the past can be seen directly above the club: the ghost of a Charles H. Fletcher Castoria ad.

Another in a string of magnificent 5th Avenue corner buildings, this one at Berkeley Place. (Remember the name: it will come up again later with a different spelling.) In Britian, the name is pronounced BAR-clay; there is a Barclay Street in lower Manhattan.

The White Cloud Laundromat. Remember the sign: it too will be seen again presently.

Two of Fifth Avenue’s older signs, on either side of Union Street, both interesting in their own way. “Fifth Avenue Pizzeria” is hand-lettered with care, with even spacing between letters: it was either done professionally, or with professional aid. Across the street is a classic signboard with slots into which pre-cut letters are arranged. Cleverly, the iron shutter gate cover has been painted the same color as the letters. I was drawn to both ads because each uses a classic Coca-Cola red and white bullet sign.

December 2007: The End of Donuts and Coffee. The next door Associated Supermarket took it over.

Union and President

There’s a brief burst of patriotism in this stetch of South Brooklyn; two lengthy streets are named President and Union, and further west, streets in Cobble Hill are called Congress and Amity. Strangely, there’s a Baltic, which seems unusual, but a few blocks north, you have Pacific Street and Atlantic Avenue; perhaps there was once a plan to name streets after oceans or seas, like the north-south avenues in Atlantic City, NJ.

Unaltered buildings, Union Street just west of Fifth.

President Street building. Its date of construction, 1886, is evident on the cornice. When the builders put in bay windows jutting over the sidewalk, they apparently had no idea the Fifth Avenue El would be built in a couple of years, rendering the apartments quite noisy.

Magnificent structure at Carroll and 5th, built in 1888 (again, one year before the el; so, viewing the building like this was impossible for the building’s first half-century, until the el went away in 1940). This, and the building front seen above at 5th and President a block to the north, were probably joined at some point in their history. The corner storefront is Café Moutarde, or as we say in the States, Mustard Eatery.

Carroll Street (like the one in Baltimore) is named for Maryland representative at the Continental Congress,Charles Carroll (1737-1832). He was the sole Roman Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, was at his death the last surviving signer, and the only one to include his hometown in the signature: “Charles Carroll of Carrollton.”

He is honored with a street name because of the Maryland troops who assisted in the Revolutionary Battle of Brooklyn at the Old Stone House in J. J. Byrne Park, between 3rd and 5th Streets and 4th and 5th Avenues.

What we now call the Old Stone House was originally constructed in 1699 by Klaes Arents Vecht, who had arrived from Holland in 1660. The house remained in the Vecht family until just prior to the American Revolution, when it was rented to an Isaac Cortelyou; his father, Jacques, bought the property in 1790, and the house continued on with the Cortelyou family until 1850 when it was sold to Edward Litchfield.

Apparently, Litchfield allowed the house to literally sink into ruin: by the 1890s only its upper floor was visible above ground level; after serving as a makeshift clubhouse for the Brooklyn Bridegrooms baseball team (who would becaome the Brooklyn Dodgers) playing in nearby Washington Park. The house was demolished in 1897, though its original construction was so tough that Gatling guns were used to force the old stones apart.

The house found an angel in Brooklyn Borough President John J. Byrne. The Old Stone House’s original foundations and brick were rediscovered, and Byrne, in one of his final acts as beep before his death in 1930, ordered its reconstruction in a park posthumously named for him in 1933. The Old Stone House received a thorough makeover in 1996 with new plumbing, electrics and roofing installed.

The Old Stone House played a pivotal role in the American Revolution. On August 27, 1776, during the Battle of Brooklyn, things looked dire indeed for the Americans, as the British and their hired hands, the Hessians, were overwhelming them in what is now the northern section of Prospect Park. Hoping to reach forts at Boerum Hill and Fort Greene, about 900 American troops retreated from what would be the Greenwood Cemetery area; they hoped to track northward. General William Alexander, aka. Lord Stirling, led a company of 400 Maryland troops that engaged British General Charles Cornwallis’ force of 2000 grenadiers and cannoneers at the Stone House to cover the retreat and, while many of the Americans were able to escape, Stirling was captured and 259 of the Maryland troops were killed. George Washington, observing the battle from what is now Cobble Hill, is said to have uttered: “What brave fellows I must this day lose.”

Signage

Back to signage: A wonderfully hand-lettered green and white Joe’s Shoe Repair sign at 237 is next to a remnant of the old Slope, His and Hers Social and Athletic Club. Across Carroll, the Knox Realty sign is standard-issue, except…

…for its lingering neon liquor store sign!

Macomb Street, running between 4th Avenue and Prospect Park West, was probably named for Alexander Macomb Sr. (1748-1831), a prosperous Revolution-era merchant born in Belfast, Ireland. Though he initially had Tory sympathies he built the mansion George Washington occupied in NYC between 1788-1790 when the US Capitol was located in Manhattan. Macomb owned vast upstate tracts.

Macomb St. was renamed Garfield Place after the US President James Garfield‘s assassination in 1881. Garfield was not initially killed by the bullet’s impact, but by treatment with unsterilized instruments, resulting in blood poisoning.

Carroll of Carroll-Turn

Fifth Avenue takes a slight jog southwest at Carroll Street, along with its brother avenues. It will make another slight southwest jog at Prospect Avenue.

I wish I knew more about these grand Fifth Avenue buildings, like this one at 2nd Street, but the guidebooks are silent about them; the Slope west of 7th Avenue doesn’t exist, according to them. As Fifth regains prominence, that situation may change. To find out anything about this stretch, you might want to consult the Sanborn property map collection at the Brooklyn Business Library (Sanborn maps online are not available to the public, as far as I know, and require passwords)

When I passed this storefront at 372 5th Avenue near 5th Street, I assumed it was an elaborate movie set (Spiderman III?) or an expensive joke, but it turns out “Brooklyn Superhero Supply” is a spiffed-up tutoring center for neighborhood kids, known as 826nyc, that opened in June 2004.

Why 826? It is an offshoot of an original center on 826 Valencia Street in San Francisco; it has a Pirate Supply Store, at which September 19 must be a big day. The whole thing was started by belles-letterman Dave Eggers of mcsweeneys fame.

Hints of the Old Slope

The New Slope is gradually filtering in. But some of the Old Slope remains… an American Legion hall and a barber shop with a hip hop graffiti signboard.

Both these signs remain extant from the 1970s; they are probably at least 20-30 years older than that.

Lighting the way

LEFT: at 5th and Douglass we see one of the few remaining remnants of a 1980s urban renewal strategy that saw new sidewalks and lampposts installed from Flatbush Avenue to 1st Street. The poles were four-sided and minimal in design. Some of these can be found on 7th as well. They have mostly been replaced by new octagon-shafted posts of a design common in NYC streets since the early 1950s.

RIGHT: Retro-longarm Type 24M Corvington pole. Originally prevalent from 1900 to 1960, new versions of this pole have appeared in an effort to prettify NYC streets over the last 10-15 years. It’s possible that the DOT thought this stretch of Fifth featured these poles in the early 20th Century, and while lower Fifth, below 37th Street, certainly did, this part of Fifth never had Corvs, but had a set of specialized poles…

We are looking east on 9th Street from under the Fifth Avenue El in 1928. The avenue, as well as other streets in South Brooklyn, had a distnctive set of cast-iron posts quite unrelated to those in other parts of NYC.

It’s quite telling that one of my first memories,from when I was 5 or 6, was spotting from a bus window one or two of these beauties that still remained on 5th on one of the corners just south of Flatbush Avenue. Till about 1960, Fifth had a mishmash of poles from different eras, until the DOT replaced them with octagonal-shafted poles.

Meanwhile, the building with the marquee is the Prospect Theater, at the time showing the feature film The Leopard Lady starring Alan Hale Senior (father of Gilligan’s Island‘s Skipper) and Robert Armstrong, who a couple of years later would capture King Kong.

The Prospect Theater as it appears today. It was designed by theater architect William McElfatrick and opened in 1914 with over 2000 seats, and survived to the late 1960s or early 1970s.

The building in the background is the Park Slope YMCA, where I took unsuccessful swimming lessons in 1968: your webmaster is a coward when it comes to water. If we were meant to swim, why, we’d have gills…

Forgotten Fan Mike Olshan remembers the Prospect Theater…

*The Prospect Theater (today it is Steve’s C-Town) was the scene of the first appearance by The Three Stooges. It was a vaudeville theater and the act was Ted Healy And His Three Stooges. Healy was a comedian working on stage, he had Shemp, Larry and Moe planted in the audience to heckle him and start fights with each other. They all went to Hollywood together, but then Healy cut the boys loose, believing he would do better in movies on his own. And he did get cast in some comic parts, you can see him as the intrusive American reporter in Peter Lorre’s excellent character study of a pathological masturbator titled Mad Love.

Well, you know what happened. Poor Ted got clipped in a bar brawl and was forgotten. The Stooges went on to screen immortality, with Shemp stepping aside for his brother Jerry (Curly), then stepping back in when Jerry became disabled. Interestingly, Shemp did better than Ted did as an independently-cast comedian, appearing in such non-Stooge movies as Africa Screams and Private Buckaroo. And he also directed a few films under his real name, Samuel Horowitz.

Two 5th Avenue mainstays, still with their old-time signs. Neergaard Drugs, on 9th St., is open 24 hours a day for those late night emergencies.

Laundromat near 11th Street. Same signmaker as the one above?

J. J. Friel Loans, advertising a Jamaica address.

Timboos, at the corner of 5th and 11th, sports the same sign it had when I was riding past every day in the early 1970s.

[Timboo’s later replaced it with a new sign, but the joint closed December 31, 2011]

On 5th near 13th Street is the old J. Michaels furniture store, now a Mandees. I bought a blue recliner here in 1987 that served, creakily in its last years, until 2001. The building has flourishes typical of late 1800s architecture.

At 16th Street, the former Berkley clothing. Its 1950s lineoleum and neon sign is still there, at least the piece jutting out over the sidewalk that’s too much trouble to take down. Compare spelling to Berkeley Place above.

5th and Prospect Avenues

Prospect Avenue was once called Middle Streetand forms the boundary between what some consider the North and South Slopes. Near Fifth Avenue, it’s dominated by the Grand Prospect Hall, built by John Kolle in 1892. It was originally an entertainment palace with assembly hall, theater, bar, restaurant and lodge rooms. After a 1900 fire, it was rebuilt and enlarged in 1903 with bowling alleys, a billiard room, a German-style oak-paneled beer hall, meeting areas, an open-air roof garden, dining rooms and a 40-foot-high ballroom, 75 feet wide and 125 feet long.

By 1981 the Prospect had fallen on hard times;that year, Michael and Alice Halkias purchased the builkding and have since sunk millions into making it Brooklyn’s premier catering hall.

Though I have never been inside the Grand Prospect Hall, I have one memory that stands out: in 1988, a woman who I had previously had an attraction to (and likely still did) was getting married, and invited your webmaster to the wedding. Unfortunately, she found out her and her fiancé’s finances apparently prevented them from having as many people as they would have liked, and I was lopped off the guest list. I wasn’t privy to where the reception would be till I rode past the hall in a car one Sunday, and there she was in her wedding dress on the sidewalk out front. Quelle surprise. Later, she and her husband had me over to dinner in Bensonhurst to make up for things, and subsequently moved to New Hampshire.

Mike Olshan on Grand Prospect Hall:

*Grand Prospect Hall was the location from which a weekly boxing match was televised live in the 1950s, sponsored by Gillette Razor Blades. Look sharp, feel sharp, be sharp! No doubt about this, I remember it clearly. And furthermore…the boxing ring is still there, in a room that Mike Halkias has kept locked and is not using. Lotsa space in that big old building, no surprise that some parts of it are locked up and preserved unused. I imagine a thick layer of dust and one or two big, heavy heavy RCA TK-60 black-and-white broadcast cameras on huge roller dollies.”

Out of the Slope

South of Prospect Avenue, north of 39th Street, and west of 5th Avenue we come to a neighborhood without a name. Some, especially real estate brokers, call if Park Slope South or the South Slope. Others call it Greenwood Heights, especially the area near the cemetery. Nobody has yet called it Sunset Park North. We’re definitely out of the Slope: frame houses replace attached brownstones on the side streets for the most part (though they will resume in Sunset Park south of 39th Street). John Manbeck, in The Neighborhoods of Brooklyn, places it firmly in Sunset Park, but since the park is 20 blocks to the south, I can’t. There’s one thing you do notice immediately:

While Greenpoint and Maspeth have a much more storied concentration of Poles, Slovaks and Eastern European immigrants, there’s also a large contingent here along Fifth between about Prospect Avenue and 25th Street, mixed with a Hispanic complement and a newer Asian movement.

The Macaulay Building, a large warehouse, announces its date of completion (1905) at the top like other period buildings along this stretch. Dahill Moving & Storage, painted atop another ad for a storage company, is emblazoned on a building across the street. Ads (like the J.J. Friel ad) were strategically placed on buildings so they could be seen by passngers on the long-vanished Fifth Avenue El. As it happens, Dahill, founded in 1928, is still in business as part of Mayflower.

The 1896 Hutwelker Building, a former stables, at 5th and 19th. You have to wonder why these elaborate building identifications were placed at the top, where no one could see them unless you happened to be looking up, or in a building across the street.

Many area businesses have been here for decade after decade, among them Eagle Provisions on 18th St., specializing in kielbasa and over 1600 varieties of beer.

A former furniture store at 5th and 19th appears to be an old theater. I noticed a faded sign on it advertising an old appliances chain, Friendly Frost; before P.C. Richard ascended to its current domination around town, there was Friendly Frost and later, Newmark & Lewis and the Wiz in the 1970s and into the 90s.

Greschler Hardware and Regio Bakery are also longtime fixtures. Unfortunately Greschler replaced its Victorian shopfront about a decade ago; Regio is still using its decades-old handpainted sign.

The brick St. John the Evangelist parochial school on 21st Street is of interest, particularly for the “primary” signs chiseled above the entrances. The church was established here in 1851, making it one of Brooklyn’s older parishes.

At left, the appearance of Mary to three children at Fatima, Portugal, in 1917 is represented in statuary.

Developers have recently noticed the “South Slope” and have erected 8 and 9-story luxury buildings that are not complimentary to the previous housing stock. More stringent laws may be needed to determine height and configuration of new construction.

Classic brick buildings are increasingly being marred by 21st-Century installations like cable TV dishes and cell phone towers.

RIGHT: 5th and 23rd. Diet Rite Cola is still around, though now rare in NYC.

5th Avenue in the 20s seems stuck in a time warp that ignores the go-go redevelopment found in Park Slope.

End of the Line

The McGovern-Weir greenhouse at 5th and 25th, plopped as it is across the street from Greenwood Cemetery stands out like a jewel in this otherwise nondescript Brooklyn corner. According to legend, the greenhouse, sporting a wrought-iron “Weir” at the top (with the added-on McGovern partner’s name) originally appeared in the St. Louis, MO World’s Fair in 1904. Cast a glance down 25th or 24th Street toward the waterfront and Lady Liberty lifts her torch in greeting.

Enter Green-Wood Cemetery through the Gothic Revival red sandstone main gatehouse at 5th Avenue and 25th Street. It was designed by Richard Upjohn, the architect of Brooklyn Heights’ Grace Church, and was constructed between 1861 and 1863. Look for the rich details: a double arch, three spires, religious reliefs with a Resurrection theme, and a bell that rings to announce every funeral procession. Also note that a colony of monk parrots has made its home in the central tower.

This page was photographed on October 3, 2005 and written October 7 and 8, 2005.

SOURCES:

Brooklyn’s Park Slope, A Photographic Retrospective, Brian Merlis and Lee Rosenzweig, Brooklyn Editions 1999

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

The Neighborhoods of Brooklyn, John Manbeck, Yale University Press 1998

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

New York City’s Best Dive Bars, Wendy Mitchell, Gamble Guides 2003

BUY this book at Amazon.COM