It all goes back to those bus rides I used to take with my mother, father or grandmother on the B63 bus in Brooklyn that runs, then as now, all the way down 5th Avenue from Bay Ridge to Atlantic Avenue. There are items filed away in the Forgottenbrain at age 6, 7, or 8, when I was fashioning lampposts out of pencils, spoons and those little lightbulbs you find in flashlights, imitative of the big posts that went by as we rode. I noticed other things besides lampposts, such as the old, decrepit-looking stone house in the park at 5th Avenue and 3rd Street, or the fact that the sidewalks on 3rd were a lot wider than the other streets. The old house, and the odd width of 3rd Street both have a lot to do with today’s mystery guest, so sign in, Edwin Litchfield…

In many ways Litchfield is the father of Park Slope, since, while converting Gowanus Creek into the Gowanus Canal beginning in the 1850s, he also purchased a full one third of all the land between the canal and what is now Prospect Park, eventually, along with other landowners, hiring architects to draw up lots and cut through streets. The opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 led to a housing boom and by 1900 many of the beautiful brownstone buildings we see today had been built.

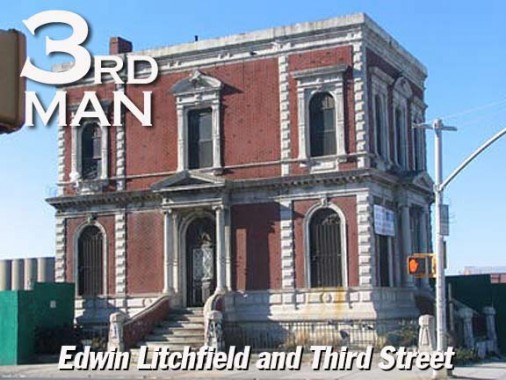

There it stands at the corner of what much of America believes Brooklynites pronounce Thoid and Thoid, catercorner to a brick wall supposedly belonging to old Washington Park, where the Brooklyn club in the short-lived Federal League played; alone by a garbage-clogged side channel of the Gowanus Canal on the SE corner of a chemically contaminated expanse slated to become, of all things, a Whole Foods supermarket – it’s the former home of the Brooklyn Improvement Company, founded by Litchfield for the express purpose of dredging the Gowanus Creek, then a fresh stream, and making it vessel-worthy. I’m not sure whether to thank him or not, since for the latter half of the 20th century when its flush pumps were in disrepair, the canal became so foul that it turned the color of Pepto-Bismol and became known as Lavender Lake.

Built in 1882 by the NY & LI Coignet Stone Company and leased to Litchfield, the Brooklyn Improvement office will be incorporated into a new Whole Foods site, that like most large construction projects is not without controversy.

While praising Litchfield, we have to consider a building he nearly destroyed, a block and a half away.

What we now call the Old Stone House was originally built in 1699 by Dutchman Klaes Arents Vecht. The house remained in the Vecht family until just prior to the American Revolution, when it was rented to an Isaac Cortelyou; his father, Jacques, bought the property in 1790.

Officially known as the Vecht-Cortelyou House, the Old Stone House played a pivotal role in the American Revolution. On August 27, 1776, during the Battle of Brooklyn, things looked dire indeed for the Americans, as the British and Hessians were overwhelming them in what is now the northern section of Prospect Park.

Hoping to reach forts at Boerum Hill and Fort Greene, about 900 American troops retreated from what would be the Greenwood Cemetery area; they hoped to track northward. General William Alexander, also known as Lord Stirling, led a company of 400 Maryland troops (this is the Maryland state flag) that engaged British General Charles Cornwallis’ force of 2000 grenadiers and cannoneers at the Stone House to cover the retreat and, while many of the Americans were able to escape, Stirling was captured and 259 of the Maryland troops were killed. George Washington, observing the battle from what is now Cobble Hill, is said to have uttered: “What brave fellows I must this day lose.”

The house continued on with the Cortelyou family until 1850 when it was sold to Edwin Litchfield, who allowed the house to literally sink into ruin. By the 1890s only its upper floor was visible above ground level; after serving as a makeshift clubhouse for the Brooklyn Bridegrooms baseball team playing in nearby Washington Park, the house was demolished in 1897, though its construction was such that Gatling guns were used to force the old stones apart; in those days they didn’t fool around, building houses to last whose designs somehow never look kitschy or out of place.

The house found an angel in Brooklyn Borough President John J. Byrne. The Old Stone House’s original foundations and brick were rediscovered, and Byrne, in one of his final acts before his death in 1930, ordered its reconstruction in a park posthumously named for him in 1933. The Old Stone House received a thorough makeover in 1996 with new plumbing, electrics and roofing installed. Colorful Maryland state flags wave at the old house, in honor of the regiment. The Old Stone House’s stock has risen as Park Slope’s has in recent years: it’s now a premier history museum.

Surprisingly, another Old Stone House in Georgetown, Washington, DC resembles this one and is nearly as old.

Walking Third

This stretch keeps its bluestone sidewalks that came very early in the street’s evolution, and decades-old wrought iron gates. NYC doesn’t have service alleys, and so trash has to go right in front.

As mentioned before I noticed at a young age that Third Street’s sidewalks are a lot wider than on parallel streets. I haven’t used a tape measure or anything but I’d estimate they’re about double the normal width from 4th to 6th Avenues, and again from 7th to the park. Between 6th and 7th, the sidewalks shrink to normal width but the roadbed widens to compensate.

So, what’s going on?

The answer lies in a grand project by Litchfield to create a wide carriageway between his Brooklyn Improvement office (the small building we’ve seen at 3rd Avenue and 3rd Street) and his mansion at the top of the Slope, now in Prospect Park (which we’ll see later). Excavations for the roadway, however, did damage to the Old Stone House, which wound up with its entire first floor buried with only the top floor exposed to air. It was then demolished in 1897 and revived from the dead in the 1930s, with the only remnant of Litchfield’s carriageway being Third Street’s unusual width.

Francis Morrone in An Architectural Guidebook to Brooklyn:

The two blocks of 3rd Street between Seventh Avenue and Prospect Park west comprise one of Park Slopers’ most beloved streets. I suspect that many a Park Sloper would say he likes it as much as he does Montgomery Place (which we will cover on a subsequent Forgottenpage). It is partly its stately width, partly its shady trees, and partly its houses. As for the last it is well to note that none of 3rd Street’s houses is itself exceptional…

…and then, of course, Morrone goes on to describe how exceptional they are.

Facing Byrne Park: no slouch either… I’ve always loved the metronomic repetitive ticktock of Brooklyn’s attached housing. Baltimore, Boston, Washington, Philly and smaller towns in the northeast have notable blocks of houses like this, but the builders of Brooklyn did it best.

Not greatly exceptional, in an entire neighborhood full of stretches like this. Your webmaster was just skunked again on a MegaMillions drawing, this one for $370 million. How else does anyone else afford this kind of splendor, I’d like to know.

I shot a working gaslamp. Other buildings here feature such lamps, but of the ones on 3rd Street, this was the only one not electrified. NYC used working gaslamps to illuminate public streets from the 1870s or so until the mid-1910s, when electric lamps finally overcame them.

Forgotten Fan Peter J., who lives on 3rd Street, says:

Many of the gas lamps are still working with gas–few are “electrified.” Most have “mantles” which glow to give off light. There are about 10-12 working gas mantle lamps on the street. The one you pictured is the only one in the “flame” style. It was recently renovated by our friends.

Not the Kitties to Mess With

Some people know how to make an entrance but Prospect Park‘s creators, Frederick Olmsted, Calvert Vaux and their army of landscapers, architects and sculptors, made a lot of them. The two bronze panthers at 3rd Street are relative latecomers, having arrived in 1898 by the chisel of Alexander P. Proctor. The marble pedestals are courtesy Stanford White, who also created the two giant pillars at Bartel-Pritchard Square 12 blocks south.

Litchfield Villa, built in Italianate style and originally named Grace Hill for Litchfield’s wife, was completed in 1857 by architect Alexander Jackson Davis. It boasts a 4-story square tower, a 3-story polygonal pavilion, and cylindrical turrets. A side porch features supports with a corn and wheat motif.

When the villa was built on a 280-foot rise, Litchfield and his family could look down the gentle slope then occupied by fields and farms toward Gowanus Creek, which the magnate would soon be straightening into a canal.

The city of Brooklyn took title to the property to include in Prospect Park while Litchfield was on a European vacation in 1869. The city leased it to him till 1883, when he left the USA after Grace’s death.

Sources:

Francis Morrone, An Architectural Guidebook to Brooklyn, Gibbs Smith 2002

Clay Lancaster, Prospect Park Handbook, Walton H. Rawls 1967

Photographed February 24, 2007. Page completed March 8, 2007.