I had always been under the impression that Stockholm Street in Bushwick and Ridgewood was so named in honor of a putative Scandinavian community that may have resided there. There was certainly a large one in Bay Ridge and Sunset Park.

I was wrong though; Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss’ handy Brooklyn By Name states that Stockholm Street was named for the Stockholm brothers, Andrew and Abraham, who provided land on which the Second Dutch Reformed Church, built in 1850 and still standing at Bushwick Avenue and Himrod Street (see this page) was built.

Bushwick and parts of Ridgewood long ago were nicknamed Old Germania Heights; dozens of breweries and German beer halls used to dot the landscape on the side streets. While there are still many Germans in NYC, former strongholds such as the East Village, Yorkville, and this area have evolved and changed over the decades.

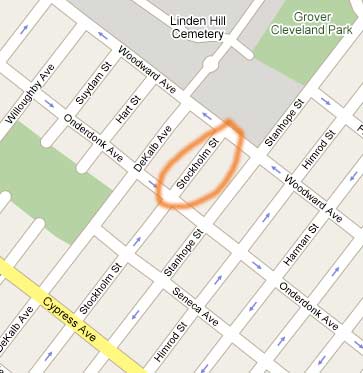

I have long been intrigued by one block of Stockholm Street in particular, the one on its northeastern end between Onderdonk and Woodward Avenues. We are officially in Queens, but the boundary is purely political.

You literally follow a yellow brick road on Stockholm Street. It is paved with dark yellow or bright brown bricks. While other streets in Brooklyn and Queens boast worn or uneven Belgian blocks (the type celebrated on my “Cobblestones” section) and in very rare cases, red brick, this is the only street in either borough bearing exposed yellow brick. The street is ballasted by St. Aloysius Roman Catholic Church on the southwest at Onderdonk and Linden Hill Cemetery on the northeast.

Stockholm Street’s main claim to fame is its 36 homes, on both sides of the street, built with yellow brick from the Bathazar Kreischer kilns of Staten Island. There are similar rows of yellow brick houses elsewhere in Ridgewood and in Long Island City, but only these have the added attraction of thin, Doric-columned porches.

When Stockholm Street was placed under the protection of the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2000 (meaning that no teardowns or drastic alterations can happen on the block, the LPC erected a sign on the block stating:

Thirty-five of the houses were constructed between 1907 and 1910, when German-Americans and immigrants from Germany were developing Ridgewood. The houses feature full-width wooden porches with columns, projecting bays, uninterrupted cornice lines and bricks produced by the Kreischer Brick Manufacturing Company of Staten Island. They were designed by the architectural firm of Louis Berger & Company and built by Joseph Weiss & Co.

As we see in the photo on the top, though, some unfortunate changes have been made to some of the Stock-homes before legislation prohibiting such alterations was passed. There’s a well-known expression, “a man’s home is his castle,” but your webmaster is in favor of aggressive legislation that would save NYC homeowners from themselves.

St. Aloysius Church, built by architect Francis Berlenbach between 1907-1917 at Onderdonk Ave. and Stockholm Street, is the largest NYC building constructed with Kreischer brick. At 165 feet in height its twin campaniles are exceeded or rivalled in the general area only by the Spanish Baroque St. Barbara’s R.C. church at Central Avenue (8 avenues to the south) and Bleecker Street.

Stockholm Street reaches its northeast end at Woodward Avenue and Linden Hill Cemetery, a Jewish cemetery occupying a roughly square area between Woodward and Metropolitan Avenues and Stanhope and Starr Streets (the NW corner is the independent Lahawith Chesed cemetery). Interred here are the longtime Republican NY senator Jacob K. Javits (1904-1986) and Joseph B. Bloomingdale (1842-1904), founder of the titular department store.

Can you spot the King Of All Buildings?

As if people need to be told. In 2008 they do.

Faces of Linden Hill. Placing photos of the deceased on tombstones is a recently revived practice, here and in nearby Mt. Zion Cemetery.

The end of DeKalb Avenue. Even though Brooklyn and Queens each have some very long streets and avenues, it’s slightly disorienting to see an avenue you know from a completely different neighborhood turn up here; DeKalb Avenue to me is rather more familiar from its downtown and Fort Greene stretches, but it makes its way east and northeast all the way to Ridgewood, as do its partners Willoughby, Greene and Gates Avenues. At Woodward and DeKalb we find a handsome cemetery gatehouse.

DeKalb does have subway stops both downtown (serving the B, M, Q and R lines) and in Bushwick (serving the L).

Photographed April 20, 2008; Page completed April 21, 2008.