On February 21st, 2012 I was laid off from a job I fought hard to obtain, and fought hard to keep. The following day I went where many Brooklynites over the decades have gone for solace and to forget: Coney Island. I had lunch at Nathan’s, which is packed and jammed 7/365 no matter the weather. I was also there to photograph Coney Island’s dwindling collection of over a century-old trolley poles, which are somewhat endangered since recent construction has eliminated several of them.

Most trolley lines in Brooklyn vanished just a few years before I was born (in 1957–I know I should not reveal my true age lest I be written off as a prematurely out of touch and outdated crackpot, but sometimes it’s essential contextually). Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, his successors, and NYC’s chief Regent and transportation czar, Robert Moses, were wedded to the notion of King Auto and the internal combustion engine, and buses had replaced trolleys in almost every case by 1956. A few trolley buses hung on in Williamsburg, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick until 1960, but these last Triceratops were at length replaced by the “new-look” GM fishbowl buses that were beginning to take command. When you think about it, NYC eliminated its trolley lines with a brutal and savage efficiency.

No fewer than three of Brooklyn’s trolley lines converged in Coney Island, at the same depot that now serves the D, F, N and Q subway lines. The #31 traveled from a large trolley terminal building (that’s still there) at 2nd Avenue and 58th Street south and southeast mainly by 5th Avenue, 86th Street and Stillwell Avenue; the #36 was an east-west route that traveled from Sea Gate to Sheepshead Bay along Surf Avenue, and the #73 was a special route I’ll describe later. And, if you count the Brighton Beach terminal that was south of Neptune Avenue and West 8th Street, the total number of trolley routes rises to seven.

According to Tricia Vita of the Coney Island blog Amusing the Zillion, trolley service began on Surf Avenue in 1893; service ended on the #36 Surf Avenue line on December 1, 1946. The Coney Island Chamber of Commerce petitioned the City Council to allow the poles to remain, without the catenary wire, so that holiday decorations could be easily run between them on a non-electric wire. And so, the poles have stood sentinel through Coney Island’s wave after wave of changes, its ups and downs, for nearly 120 years.

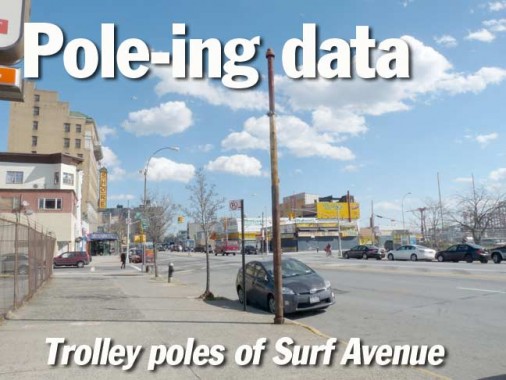

Of the 64 poles that were allowed to stand between West 5th and West 21st, we now have 43 poles remaining, as the Brooklyn Cyclones’ MCU Park construction and recent teardowns by Thor Equities claimed several. As the rust permeates them they will probably become unstable and will get torn down. They’re worth a look, if only to ponder what they have figuratively witnessed over the century.

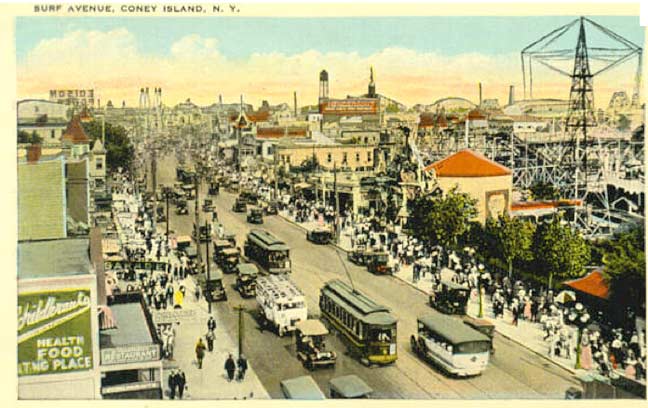

A postcard view of Surf Avenue looking east from about West 16th, where Steeplechase Park was located. You can clearly see a pair of trolley cars plying the center of the street. The tracks were set amid Belgian blocks.

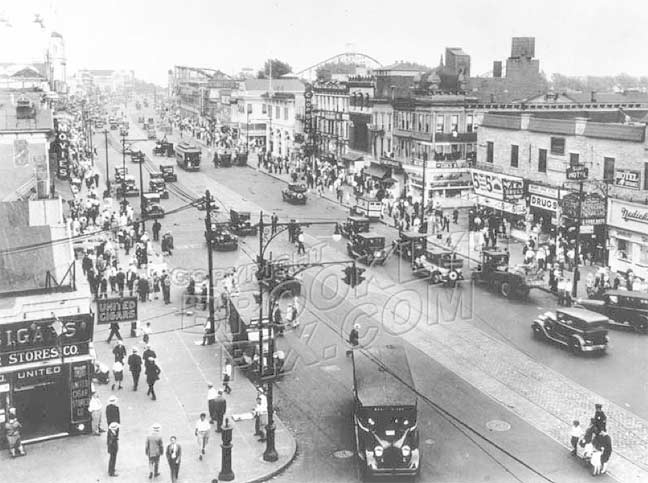

Surf Avenue looking east from the Loew’s Theatre at Stillwell Avenue in the Dirty Thirties. Just about everything in this photo has now been torn down, except for a couple of buildings on the south side (on the right) in the center, under the Cyclone, which is of course still there.

On the right, what looks like a cop on horseback crosses a kid on Surf Avenue. You can see a trolley car a couple of blocks ahead. All the guys wear straw hats. brooklynpix

In the early 1940s tracks pass by the Cyclone. From Stan Fischler, Confessions of a Brooklyn Trolley Dodger

A car picks up passengers outside the old BMT subway terminal at Surf and Stillwell. Note that you had to come out to the center of the street to get on. Today, you’d be steamrolled by the Surf Avenue would-be hot rodders. OK trolley fans, what make? Stan Fischler, Confessions of a Brooklyn Trolley Dodger

Surf Avenue looking East from West 12th. The old Luna Park, which was operated continuously in season from when it opened in 1903 to when it burned down in 1944, is on the left. A new Luna Park, which built an entrance gate that closely resembles the old one, opened on Surf Avenue’s south side in 2010.

Everything in this photo, except the trolley pole on the right, has vanished. brooklynpix

Kids heading for the beach cross Surf Avenue at West 15th in 1956. Surf Avenue has evolved. The trolleys have gone, but one pair of tracks has still not been paved over. The Loew’s is still showing movies (can you imagine a day at the beach, dinner at Nathan’s and a movie? You could do that once). Note the poles on the left and right. They’ve been painted kandy-kolored red, blue and yellow, and sheaves of flags are festooned on specially affixed holders.

The peaked roof in the center belongs to Henderson’s Dance Hall, which was torn down in 2010 and replaced with a one story bland structure. Nathan’s holds forth as it has since 1916. brooklynpix

This is the same pole in 2012, still bearing traces of the kandy-koloring.

Another trolley pole on the south side. Surf Avenue has become very wide open west of the amusement area, as a lot of buildings have been torn down with no replacements; there’s a lot of school bus parking lots.

MCU (Municipal Credit Union) Park, formerly KeySpan Park (when you have a corporate sponsor, the name of your ballpark changes every few years) is the home of the Class A Brooklyn Cyclones, an affiliate of the New York Mets. A statue outside the park, unveiled in 2005, recalls Dodgers shortshop Pee Wee Reese’ show of solidarity with Jackie Robinson when he broke the MLB color barrier in 1947, and was subjected to taunts and attacks from other players, especially ones from the South.

Outside MCU Park, all the trolley poles on the south side of the street were removed during construction, but resume at West 19th and continue to West 21st. The trolley poles west of that were presumably removed after the line shut down in 1946. The line continued to West 37th Street and the entrance to the private complex Sea Gate. West of here, Surf Avenue is dominated by drab high-rise people storage units.

A sentinel from the 1890s continues to oversee Surf Avenue in front of a particularly depressing old folks home.

Trolley poles, as a rule, unlike NYC’s cast iron lampposts from the 1890s and onward, are generally devoid of ornamentation or embellishment except for a top knob. Some poles were used to carry flags and still have the holders.

The bases have a slightly wider section. You can see the effects rust and sea spray have had. I see traces of a possible white paint job.

If you walk up a side street (this case West 17th) from Surf, just south of Mermaid, you find particularly lengthy driveways with the backs of buildings facing them. This is the route of the Nortons Point Trolley (#73), which left the Stillwell Avenue terminal via a rampway, descended to street level and continued in its own right of way all the way to the tip of Sea Gate via a shuttle trolley. Sea Gate originally featured a casino run by a fellow named Norton where the current lighthouse is located. His name has stuck all these years. The trolley ran until 11/7/1948, about two years longer then the Surf Avenue line.

While it was running, western Coney Island had a decidedly different, much more small-town atmosphere, before all the high rise monsters arrived in the 1950s and 1960s.

I don’t think any of the Norton’s Point trolley poles have survived but you never know.

An excerpt from a 1929 Belcher Hyde atlas of Coney Island. Note the black and white striped lines on Surf Avenue and the right of way: they depict trolley tracks. These maps are invaluable as a depiction of what was there in 1929, with everything down to the house numbers delineated, but of course, they’re a time capsule.

Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace, Mermaid Avenue and East 17th Street. The parish has been in existence since 1901. The surprisingly thorough parish history contains an anti-Mosesian narrative:

Over the decades, the destinies of the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace and America’s Playground would be inevitably intertwined. Coney Island lost Dreamland to a massive fire in 1911. In 1944, Luna Park from Surf Avenue to Neptune Avenue suffered the same fate. The surviving section of the park from Neptune Avenue to the subway yard continued to operate for the remainder of the season; then it, too, closed. During the decades of the fifties, sixties and seventies (the era of Robert Moses’ much-

Through the longtime devotion and generosity of the Tilyou family to the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace, they were restored that spring in time for the annual “Catholic Day.” However, the escalating crime and gang violence, as well as the overwhelming competition from Robert Moses’ 1964 New York World’s Fair was too much to overcome and the great “funny place,” Steeplechase, closed forever. Moses’ triumph was complete; he had successfully helped eliminate the last of the three great Coney Island theme parks. At the moment of its closing, two bells sounded that indicated the passage of time, and the numerous lights went out for the last time. In 1965, the Tilyou family sold the park to developer Fred Trump, who then subleased some of the property to small independent ride operators and concessionaires…

In 2000, the abandoned Thunderbolt was suddenly condemned and demolished by the City Buildings Department as “unsafe” on the orders of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (he saw it an “eyesore” next to the new Keyspan Park), just before the City Council was about to meet with property owner Horace Bullard and consider landmark status and funding for restoration and new operation. Fortunately, were two bright spots that kept classic amusements from leaving Coney Island forever in spite of the City’s efforts to wipe them out completely. One was the establishment of Astroland Park in 1962, built on the site of the old Feltman’s Hot Dog Emporium, by Dewey and Jerome Albert. The Albert family later took over management of the National Historic Landmark Cyclone rollercoaster in 1974 after it was purchased by the City of New York. The other was when Tarrytown pushcart vendor, entrepreneur, restaurateur, and very frequent Coney Island vacationer Denos Vourderis purchased and saved the former Ward’s Kiddie Park in 1981.

Give that link a look — it definitely highlights the recent history of Coney Island in a refreshingly pointed manner.

At the northwest corner of Surf Avenue and West 16th is the last vestige of the Seven Seas Restaurant, now a parking lot.

Directly in front of it is a snapped-off trolley post.

The present set of Nathan’s red, green and yellow neon signs have been in use since at least the 1950s. Though Nathan’s is now thought of as a fast food place, the Coney Island flagship has the most varied menu, offering a large range of seafood from clams to frog legs. As you can see on the sign, it’s still identified as a delicatessen. In recent years, Nathans has attracted national attention every 4th of July for its famed hotdog eating contest.

Remember the photo above of Surf Avenue and West 12th? Here’s the trolley pole, the only thing remaining from the photograph. Discount furniture stores have replaced the carousel and the old Luna Park; the Houses named for the park form the backdrop.

This 1917 building at Surf and West 12th was originally a Child’s Restaurant and today is home to the Coney Island Museum and Sideshows By the Seashore, a taste of Coney Island’s old sucker-born-every-minute atmosphere.

Affixed to the building are works by Coney Island’s first lady of poster art, Marie Roberts.

Born and raised in Coney Island, Marie’s family has had strong ties to the community for several generations and her art reflects this deep bond with the landscape. She says that her “father’s family was involved in Coney Island at the turn of the 20th century; my grandfather was acting battalion chief of the Coney Island District until his death in 1924. My Uncles Harry and Guy were at Dreamland the night of the fire. I have an uncle buried in the Gravesend Cemetery. My father claimed he never got out of the 6th grade because he was too busy watching the horses cross the finish line at the Gravesend track. My Uncle Lester was the talker for the Dreamland Circus Sideshow in the 1920’s.” For the Love of Brooklyn

In front of the new Luna Park and Cyclone, the old trolley poles have been put to work carrying electric wire and sidewalk spotlights, and a new red, white and blue paint job in the order of the former red, yellow and blue.

The Cyclone rollercoaster, which I have never ridden since I am a sniveling coward, has been part of the Coney Island scene fro 9 decades. The Dewey Albert on the street sign is the owner of the famed Astroland amusement park, of which the Cyclone was a part from 1962-2008. The Cyclone was declared a NYC Landmark in 1988 — the Thunderbolt, opposite the old Steeplechase Park, wasn’t, which enabled its decline and destruction by the city in 2000.

The success of 1925’s Thunderbolt and 1926’s Tornado led Jack and Irving Rosenthal to buy land at the intersection of Surf Avenue and West 10th Street for a coaster of their own. With a $100,000 investment, they hired Vernan Keenan to design a new coaster. A man named Harry C. Baker supervised the construction, which was done by area companies including National Bridge Company (which supplied the steel) and Cross, Austin, & Ireland (which supplied the lumber). The Cyclone was built on the site of America’s first roller coaster, known as Switchback Railway(which opened on January 16, 1884). The final cost of the Cyclone has been reported to be around $146,000 to $175,000. When the Cyclone opened on June 26, 1927, a ride cost only twenty-five cents compared to the $8.00 in the 2011 season. wikipedia

In the background we can see one of the two Brightwater Towers, a high rise constructed in the 1960s.

The only rollercoaster I ever rode was a relatively modest one indoors at the Mall of America in Minneapolis in 1993. I didn’t particularly enjoy it and got none of the thrill rollercoaster fans get on these things, but don’t let me stop you.

Double-barrel elevated train action north of Surf Avenue and West 10th. Because of track capacities at the Stillwell terminal, the express Brighton (the B) makes its last stop at the West 8th Street station. In the background are the Luna Park Houses, built behind the old amusement park locale.

The last pole remaining as you go east on Surf Avenue is at West 5th Street and Asser Levy Park. Older maps show it as Seaside Park, one of Coney Island’s oldest, having been acquired as parkland in the 1880s. It was renamed for one of the first Jewish settlers in New Netherland: he and his associates arrived as refugees from Brazil in 1654. Levy became the first Jew to own real estate in North America. The park is famed for its Seaside Summer Concert series; attractions in the 2011 series included Aretha Franklin, Joan Jett, and the Monkees, with Davy Jones making one of his final appearances.

These poles were removed in the summer of 2019.

3/4/12