I had a job interview in Soho during the week [June 2012] and after it was over, there I was in the dead dog 95° heat in Soho in my good suit jacket, good pants and dress shoes. This was an outfit not far removed from what I usually wear on FNY voyages of discovery — I have not worn shorts outdoors since 1966, when I was nine. (I gave up dressing like a child before I was no longer a child.) I had my Panasonic Lumix, as always, because you never know. I decided to walk the length of Prince Street, because I knew that street has some historic artifacts, as well as a couple of surprises. I went east on Spring to the Bowery and then a block north, and then Prince all the way to 6th Avenue.

After the British evacuated NYC in 1783 after the Revolutionary War was over, the City decided to expunge most official names associated with the Crown. King’s College became Columbia College, later Columbia University. Duke Street became Stone Street. Queen became Pearl. King George became William.

Some names have remained Briticized to this day — the county names of Kings and Queens, as well as Brooklyn’s King’s Highway, which lost its apostrophe long ago. There’s also Prince Street, which has stubbornly remained royal. Guidebooks say it’s a leftover from when the Brits were in charge, but by 1783, Manhattan was undeveloped, except for a few isolated patches, north of the City Hall area. The earliest map I can find with a Prince Street is this one from 1803, and that was just on paper — the eventual street layout looks quite different. So, I’m not sure what the story is. (And before you say King Street, that Soho street northwest of Prince honors Rufus King (1755-1827), the statesman and abolitionist who served in the US Senate and ran unsuccessfully for vice president and later, president, losing to James Monroe in 1816.)

NEW MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, 235 Bowery opposite Prince Street. I have yet to visit the major new art museum, which opened its doors in 2007. It’s been uniformly praised by architecture critics and its designers, Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, were chosen as 2010 laureates in the Pritzker competition, the biggest prize in the architecture game. Your webmaster, though, is a Philistine, and to me the building looks like 6 aluminum boxes stacked on top of the other, haphazardly. I’d have to go inside, though, to really pass judgment. The New Museum was founded in 1977.

The NW corner of Prince and Elizabeth Streets is dominated by a 6 floor what I assume is a walkup. The Italian restaurant on the ground floor has a very faded sign that is barely legible.

When you walk around Soho, store signage is a big part of the experience. Both of these establishments, a café and a high-end shoe store, use spare, stark signs with Copperplate-like lettering and a black and white color scheme.

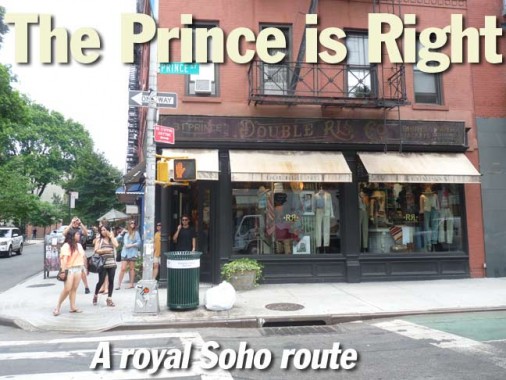

The sign on the corner store at Prince and Mott, Double RL (Ralph Lauren) & Co., has created a tribute to ancient, floridly-lettered signs from the 19th or early 20th Centuries that sometimes turn up when newer signs that were on top of them are removed. Its California sister store does something similar.

OLD ST. PATRICK’S CONVENT and GIRLS’ SCHOOL, 32 Prince, was built as the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum from 1825-1826 in a Georgian-Federal style.

The Roman Catholic Benevolent Society, established in 1817, was the oldest charitable institution in the Archdiocese of New York. At that time, parentless Catholic children were lost to the faith if they were taken in by Protestant orphan societies. From the beginning, the society was administered by the Sisters of Charity. The first building, located at Prince and Mulberry Streets, opened with 30 inmates, but within a few years was overcrowded. In 1826, a new building was erected on Prince and Mott Streets, but by the 1840s, it, too, was badly overcrowded as was St. Joseph’s Half-Orphan Asylum on West 11th Street. In 1845, Archbishop John Hughes appealed to the city for land on which to build a larger facility, and was offered the entire block between Fifth and Madison Avenues from 51st to 52nd Streets. The deed, signed on August 1, 1846, directed that the rent would be one dollar per year as long as the property was used to house orphans. At that time, Fifth Avenue was not paved and the area was relatively uninhabited. A few years later, in 1852, Archbishop Hughes would purchase the block directly to the south for a new cathedral that was begun in 1858 but not consecrated until 1879. American Guild of Organists, whose website is a godsend for church-oriented information.

OLD ST. PATRICK’S CATHEDRAL, 260-264 Mulberry Street between Prince and East Houston.

For the full scoop on this venerable church building, see my December 9, 2010 ForgottenSlice.

Jesus may have been able to clear the moneychangers out of the Temple in Jerusalem before He was crucified there, but so far, He’s done nothing about the ones who have set up outside Old St. Pat’s high wall, built to keep out the anti-Catholic mobs and Know-Nothings in the Gangs of New York era of the mid-1800s who threatened to burn down the place. (I’d imagine the pushcarts are there with the full cooperation of the parish).

That high wall clashes with the world of the early 2010s, where stories-high advertisements and street art compete for attention.

One of the abiding mysteries of eastern Soho, for me at least, is why the NW corner of Prince and Mulberry has been an empty lot for as long as it has. It’s some of the most desirable properties in town, so its owner must be charging something astronomical to build something there. Anyone from the Curbed world want to venture a guess?

Prince and Lafayette Streets. There are still a lot of building ‘rears’ (these face Crosby) facing Lafayette, which is one of the youngest north-south streets in the area. It was created within a few years of 1900 by extending Lafayette Place south from Bleecker along the paths of the former Marion and Elm Streets (pieces of which still exist as Cleveland Place and Elk Street, among others).

This is approximately the spot where President James Monroe died on July 4, 1831. Presidents Adams and Jefferson had died on July 4, 1826.

SE and SW corners, Crosby and Prince Streets. Crosby, which runs from Howard north to East Houston west of Broadway, is the home of Housing Works and its Bookstore Cafe, the ch-chi Crosby Street Hotel, and an increasing number of boutiques, but has always had a rough and ready appearance:

While SoHo swells with shoppers and strollers, Crosby Street works for a living: There’s a wholesale produce market, hardware stores, warehouses, delis, and loading docks for the big box stores on Broadway. At noon, white-uniformed chefs huddle for a smoke break at the back entrance to the French Culinary Institute, and delivery trucks idle on the sidewalks. Crosby Street

Pictured are a trio of campaigners from the 1880s, still working hard after over 120 years.

Lest anyone think the street was named for the greatest recording artist of the 20th Century, it was named for a philanthopist named William Bedlow Crosby, a grand nephew and chief inheritor of Henry Rutgers, who owned hundreds of acres of land in Soho in the late 18th and early 19th Century.

Three separate institutions on the SW corner of Mercer and Prince: 94 Prince, Fanelli’s Cafe, and the neon Fanelli sign, which has seen generations of duty. 94 Prince, a 5-story brick building, looks a bit out of place next to its cast-iron front brethren — the building first appeared in 1857 when it was built by Herman Gerken, a German immigrant landowner. In both the previous wood building to occupy the site and the brick structure after, groceries were sold from a shop on the ground floor. At the time, alcoholic beverages including hard liquor were sold in general stores of this type. The rest of the building was divided among living and manufacturing space.

The ground floor 94 Prince continued to be used as both a place to buy liquor and as a tavern through a succession of owners beginning in 1863. A Nicholas Gerdes operated the tavern from 1878-1902, and his name remains inscribed in the transom over the front door; his liquor licenses decorate Fanelli’s walls. Michael Fanelli arrived in 1922 with Prohibition in full thrall, operating the place as a speakeasy until repeal. (The “café” sobriquet was first used during Prohibition to fool the coppers.) The Fanelli family owned the bar until 1982 when it was sold to Hans Noe.

(information from Richard McDermott, who has voluminously researched NYC’s venerable taverns, including Mc Sorley’s on Eat 7th Street. Another thorough description can be found in Ellen Williams & Steve Radlauer’s Historic Restaurants and Shops of New York)

109 Prince, SW corner Greene. I call many of the cast-iron front buildings in Soho “wedding cake buildings” since they appear to be multi-tiered confections.

Ornate cast iron facades were originally used to spruce up pre-existing buildings, kind of like brickface and stucco, but was later used in new construction as well. There are approximately 250 cast iron buildings in New York City, most of them in SoHo and mostly dating from the mid to late-1800′s. An American invention, cast iron facades were not only less expensive to produce than stone or brick, but also much faster, as they were made in molds rather than carved by hand, and stuck to the face of buildings. In addition, the same mold could be used for multiple buildings and a broken piece could easily be recast, making it a very efficient decorative method. Because iron is pliable, ornate window frames could be designed, while the strength of the iron also allowed for enlarged windows that let floods of light into buildings as well as high ceilings in vast spaces with only columns necessary for support. sohomemory

112 Prince, on the south side of the corner, was completed in 1890 and is accented by a trompe l’oeil painting by Richard Haas. See if you can spot the cat in one of the open windows when you pass by.

120-126 Prince is a two-story brick building that has a pair of what appear to be authentic century-old metal signs. See this FNY page from May 2010 for a closer look.

The NW and NE corners of Prince and Wooster feature two apartment towers that appear similar in appearance — there is likely a story behind that.

Vesuvio Bakery is at 160 Prince Street in SoHo. The green facade is one of the distinctive images and colors of downtown NYC which inhabitants would recognize immediately – the shade of blue-green is so striking that nearly everyone that sees the shop comments on the color. The bread is handmade daily and presented simply by being piled up in helplessly beautiful stacks in the windows. The shop is a fixture of the old Little Italy in NYC which has survived many generations, a tremendous feat in this city of constant change, and is still family-owned.

Recently, a few small tables and a wider variety of food have been added. This place became special by preserving itself on its own intimate terms while the neighborhood has gentrified exponentially around it. Seeing it is like taking a few seconds of a visual calming and restorative meditative break. NY Daily Photo, 2006

The bakery was a Soho institution between 1920 and 2008, and presented the same face to the neighborhood for decades — and still does, after its takeover by the City Bakery, which reopened it as Birdbath Bakery in 2009.

Get a discount if you arrive by bike? What if you walk in? That’s green, too.

I wonder what posessed the owners of these 2 buildings on Prince opposite Vesuvio Bakery to paint their buildings the identical shade of pink.

There are other pink or magenta buildings around town as well [Ephemeral New York]

These 3 establishments, all clustered together on Prince near Thompson, follow the philosophy that to be truly successful, you have to know what you are first.

St. Anthony’s Convent, on Prince and Sullivan, was built in 1955 but is associated with the St. Anthony of Padua Parish, established in 1859, the oldest parish in NYC associated with Italian immigrants.

Father Fagan Square/Park was established in 1928 when 6th Avenue was extended south along the new IND Subway. The buildings on the left originally had Macdougal Street addresses, but were renumbered for 6th Avenue. Father Richard Fagan, a parish priest at St. Anthony’s, perished in a fire at the rectory in 1938 while saving the lives of two fellow priests. He was 27 years old.

Hate to end on a down note, but Prince Street ends here at 6th, where Charlton Street begins.

6/25/12