I like to visit Boston every few years (I haven’t gone since 2006 — a lack of time and now, money has prevented a trip since then) and I usually stay in Brookline, a suburb/small town west of town famous for being the birthplace of John F. Kennedy. The town is throughly urbanized in spots, while very small town like in other places — for example, you sometimes encounter verdant squares like Longwood Mall (above) — it’s a public park, but unlike those in NYC, because it’s completely grass and trees, maybe a pedestrian path, and the surrounding roads are sans sidewalks.

We don’t have anything like that in NYC — it’s a megalopolis and too heavily urbanized for the Longwood Mall style layout to work well — but you do occasionally come across compact parks that occupy a single square block or two. I was meandering around Greenpoint with Miss Heather and husband Sanford a few weeks ago and came across one of my NYC favorites, Monsignor McGolrick Park, which can be found between Russell and Monitor Streets and Driggs and Nassau Avenues.

The park features winding paths that are separated from the grassy malls by iron railings, as well as numerous benches that the area homeless find attractive, as well as three substantial public monuments, which I will discuss in turn here.

The park was set up by the City of Brooklyn in 1889 with a funding assist from assembly Winthrop Jones; when it opened in 1891 the park was duly named Winthrop Park — possibly, there was a pre-existing Jones Park. The park was renamed Monsignor Edward J. McGolrick Park, in honor of the pastor of the nearby St. Cecilia’s Roman catholic Church from 1888 until his death in 1938. McGolrick, an Irish immigrant, was a major fundraiser for the parish, which built new church, convent, rectory, hospital, lyceum, school, and playing field under his direction.

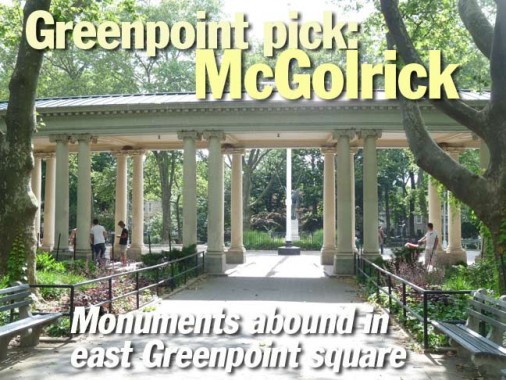

In 3 consecutive decades over a span of 29 years, three major additions were made to Winthrop Park. The first of these was executed in 1910: a triumphant crescent-shaped shelter pavilion designed in 1910 by famed architectural firm Helmle and Huberty. The brick and limestone creation features an elegant wood colonnade connecting two buildings. Each building served as a comfort station, one for men, and the other for women. The pavilion was designed to invoke the feeling of 17th and 18th century French garden structures. The structure is currently listed on the National Register and is protected as a New York City landmark. It was reconstructed in 1985 — some critics felt it strayed too far from the original design, so it was again rebuilt in 2001. It was declared a NYC landmark in 1966.

The partnership of Frank Helmle and Ulrich Huberty executed some of Brooklyn’s most beautiful buildings, including St. Barbara’s Church, the tallest building in Bushwick, as well as the Tennis and Boat Houses in Prospect Park.

Greenpointers who served in World War I are remembered by this Angel of Peace statue by German immigrant Carl Augustus Heber, dedicated in 1923. On three sides of the pedestal are inscribed names of major battles: Argonne, Somme, Chateau Thierry.

Here, in a park that is still at the heart of working-class Brooklyn, the “angel of victory” carries the palm and holds out the olive branch. Like all our angels she is young and beautiful, and her face, tipped slightly askance, bears that indefinable look of longing and exaltation that seems to come from another world, bearing hopes that we would never dare but for her blessing. The pedestal’s words ring with the soul of the Great War innocence, beginning: “To the living and dead heroes of Greenpoint who fought in the World war because they loved America…” –from Out of Fire and Valor, Cal Snyder

The John Ericsson (Monitor and Merrimac) Monument by Italian immigrant sculptor Antonio de Filippo, dedicated in 1938. The Swedish-born engineer Ericsson (1803-1889) designed the Monitor, the USA’s first ironclad vessel, at Greenpoint’s Continental Iron Works in 1861, and engaged the Confederate States’ Merrimac at Hampton Roads in 1862. Less than a decade after the battle, William Street was renamed for the famed warship. 2012 is the sesquicentennial, or 150th anniversary, of that naval battle, which ended in stalemate.

I have always been fascinated by abandoned luncheonettes; Sanford showed me this one, complete with its 1950s plastic lettered sign and Coca-Cola plaques on the north side of the park, corner Nassau and North Henry. I couldn’t shoot the interior through the window, because of too much sun glare, but it looks untouched since it closed years ago–everything is still in place.

Attached homes, North Henry Street. When the city of Brooklyn annexed Williamsburg(h), Greenpoint and Bushwick in 1855, this street was just plain Henry, but it was given the name North Henry so there’d be no confusion with Brooklyn Heights’/South Brooklyn’s Henry Street, a few miles to the southwest.

However, despite the fact that Brooklyn has two West Streets, two West 9th Streets, two Atlantic Avenues, two Stewart Avenues, etc., confusion doesn’t reign.

Church of Christ at Greenpoint, 199 North Henry. I know next to nothing about this modest neighborhood church–its website is no help about the building, as most church websites are worship-directed and don’t talk about architecture.

Across the street, a lady bares gifts.

Norman Avenue and North Henry Street. As elsewhere in Greenpoint and North Brooklyn, a factory has been converted into artists’ space.

The Newtown Creek Wastewater Plant, aka. digester eggs, aka Shit Tits, dominate views in Greenpoint and in Hunters Point, across Newtown Creek. The plant actually has a visitors center, which has become one of Brooklyn’s top ticket attractions. They are lit purplish-blue at night.

The digesters […] process up to 1.5 million gallons of sludge everyday. Each egg, clad with low reflectivity stainless steel, is 145 feet high and 80 feet in diameter. The eight eggs were welded on site from pieces that were brought from Texas and fabricated by Chicago Bridge and Iron. It took three months to assemble each one. Although the weight for each egg is around 2 million pounds when empty; it is calculated that they may weigh up to 32 million pounds when processing sludge. The blue lights illuminating the eggs were designed by artist Hervé Descottes of L’Observatoire International, an American/French company. Hervé Descottes is known for lighting projects ranging from the diverse architecture of Steven Holl and Frank Gehry, to local projects such as Lincoln Center, the Highline, and Columbus Circle. The first four eggs came into service on May 23 [2008] and the rest will come online by the end of the year. NYC

The massive Miller Building stands sentinel on Greenpoint Avenue east of the digester eggs. Now used for warehousing, the exact origins of the Miller Building, and the identity of Miller, are shrouded in mystery and legend. Mitch Waxman of the Newtown Pentacle has peeled back the layers and approached the truth.

And elsewhere in Greenpoint…

I snapped photos of such scenes and signs that attracted me, such as this Catholic War Veterans post on Lorimer Street, whose hand-lettered sign features an Irish cross.

This is an ancient faded FTD Florist sign at Meeker Avenue and Lorimer. No doubt supposed to attract the attention of whizzing motorists on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

There are two species of fire hydrants painted with flags in red, white and blue on NYC streets. By far the older are those commemorating America’s bicentennial (200th anniversary) in 1976, which tend to be quite faded; and these, which were done in the aftermath of the 9/11/01 terrorist massacres.

Pete’s Candy Store, on Lorimer, is quite unprepossessing when closed, sporting some old Coca-Cola medallions. Like the old Y. Berra axiom, nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded — I was turned away by the crowds when I tried to attend one of the bar’s popular trivia contests, which I’m confident my team would have won.

Engine 229, Richardson Street, one of Brooklyn’s many century-old brick firehouses. The company was organized as Engine 29 in 1890 and renumbered 229 in 1913. The company has been featured in the CBS-TV drama Blue Bloods.

Brooklyn Fireproof Sash & Door Company, 97 Richardson just west of Meeker. The date of construction, 1907, can be found on the cornice. The company was apparently out of business by 1941. The company made metal attachments to doors to check the spread of fire — sheetrock and asbestos were also used. Walter Grutchfield has the whole story.

The magnificent 19th Police Precinct building, on the corner of Herbert and Humboldt Streets, has been put to use as affordable rentals after a lengthy period of abandonment. The stable, next door, is also marvelously intact.

St. Cecilia school, Monitor Street

On Monitor Street the former St. Cecilia parish school was the former home of artists’ studios until the Church kicked them out in the summer of 2011.

Saint Cecilia’s School opened in 1906 under the guidance of Monsignor McGolrick in the newly constructed School building. The School was a result of those in Greenpoint’s working class community and was among the largest parochial schools in the United States during the 1930s and 1940’s. From the 1970s to 2006, Sister Miriam S.J. lead the school, and has left her mark as a legend. She led with true sincerity and was loved by students and staff alike. Due to declining enrollment beginning in the 1970s, the parish school eventually fell on hard times by the early 2000s, culminating with the 2008/2009 School Year when only 222 students registered. With only 107 students registered for September 2009 and a current as well as future six digit debt, it was determined that the school could no longer be operated and the new pastor, Rev. James Krische, had no choice but to close the Parish School after it had served the Greenpoint community for 101 years. The closing came as a surprise, causing conflict, unrest and saddness in the parish community. wikipedia

Thus, the building has seen both its school and studios close in the last few years.

7/1/12