Lispenard is one of those only-in-New York street names you find downtown, such as Desbrosses and Laight — neither of which I am sure how to pronounce. I think it’s the only street that begins at West Broadway and ends at Broadway — it runs just two blocks.

Like most of those only-in-New York street names, it was named for an original landowning family, or a person associated with Trinity Church. In this case, the street was named for either Anthony Lispenard (1640-1696) or grandson Leonard Lispenard (1714-1790). Anthony Lispenard was a refugee from 17th Century France, as many French Huguenots emigrated to the Colonies in the 1700s. He became an alderman, and assemblyman and a treasurer of King’s College (which developed into Columbia University). He married into the Rutgers family (the Lispenards also intermarried with the Bleeckers) and came to own much of the property that is now west of Broadway and south of Canal. Unfortunately, back then much of that was swampland, which became the source of troublesome mosquito infestations before the area was developed and built up with the aid of landfill.

It was a wild spot, remaining in a primitive condition — part marsh, part swamp — covered with dwarf trees and tangled underbrush. Cattle wandered into this region and were lost. It was a dangerous place, too, for men who wandered into it. To live near it was unhealthy, because of the foul gases which abounded. About the year 1730, Anthony Rutgers suggested to the King in Council that he would have this land drained and made wholesome and useful provided it was given to him. His argument was so strong and sensible that the land — seventy acres, now in the business section of the city — was given him and he improved it. At the northern edge of the improved waste lived Leonard Lispenard, in a farm house which was then in a northern suburb of the city, bounded by what is Hudson, Canal and Vestry Streets… Nooks and Corners of Old New York, Charles Hemstreet, Scribner’s 1899)

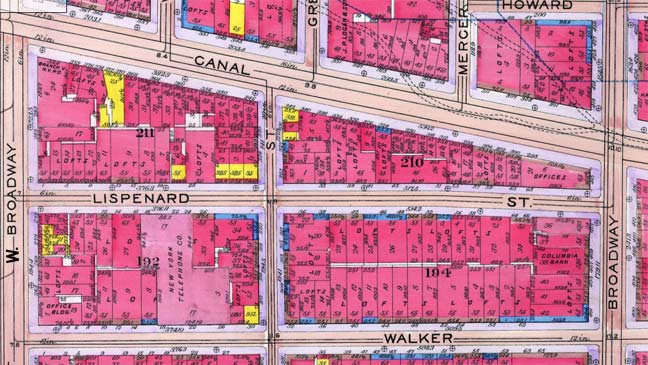

Something had always puzzled me about Lispenard Street. It’s not perfectly straight — there is a very slight bend to the southeast as it approaches Broadway, about one degree, maybe two. You can see that reflected on this atlas plate. I researched what happened: when Lispenard was laid out and opened in 1809 it took an abrupt turn to the north and met Canal at Mercer Street. In 1821 it was decided to close that bend and run Lispenard straight through to Broadway. Apparently that wouldn’t have left room for anything to be built on Broadway between Lispenard and Canal because of the latter’s slanting route. So, it was given an ever so slight jog to allow more room…

The First National City Bank of New York building (which later became Citibank) has occupied that little bit of territory on Broadway between Lispenard and Canal for many years. This triangular space was once the location of Brandreth House, a hotel run by one Doc Brandreth, a dope peddler who later did time in Sing Sing. On the hotel’s steps on July 23, 1859, Virginia Stewart was shot and killed by her lover Robert C. MacDonald, who had pursued her from North Carolina. He killed himself with opium while awaiting trial in the Tombs. NY Songlines

A waiter had been shot and killed at the Brandreth House one year earlier. [NY Times]

This is a grouping of 5-story office buildings built in 1866 and 1867; most have their dates of construction written on their rooftop pediments. 1st floor fronts are made of cast iron. The grey building in the center, which says “Erected 1866,” was built for Daniel and Ambrose Kingsland, oil and shipping merchants. Daniel was president of Chemical Bank and a patron of the Broooklyn Academy of Music. From 1851-1853 Ambrose Kingsland was mayor of New York under the Whig banner from 1851-1853, and while in office he appropriated funds for what would become Central Park.

Even though this block of Lispenard Street is landmarked, that doesn’t mean things can’t fall into disuse and decay; witness the ground floor of #43. It’s aged rather genteel-y, though, with its iron Corinthian columns gradually rusting, and accumulated street scrawlings and stencillings adding to an aura of painless starvation. Like most buildings on the north side of Lispenard this is actually the back end of a building fronting on Canal Street, in this case, #324. The Canal street end was built in 1864 while the back end on Lispenard was added in 1876.

Pearl Paint, the art supplies favorite at 308 Canal Street, once had this branch, the Pearl Craft Center, at #42 Lispenard. In 2012 it still had the trademark Pearl Paint ground floor red paint job. Pearl opened in 1933 and its main branch on Canal is still doing well.

While I mentioned #40 Lispenard above, #38, on the right, is actually just one of the frontages for this building, which is actually L-shaped and wraps around the corner building at Church and Lispenard to another front at #315 Church Street, and it was also built between 1866-1869 for the Kingsland brothers; in fact the pediment of the Church Street front is marked…

…”The Kingsland Buildings 1967.” Other buildings from the same era, 1865-1870, are along the east side of Church Street, while the west sude of Church Street doesn’t have any comparably aged frontings because of a 20th Century street widening project.

This dental office at #44 Lispenard has gone out of their way to celebrate Halloween. The real horror begins when you get in the chair and on comes the drill.

Yelp.com gives them a panning…

#39-41, the Clark Building, is the back end of #332 Canal Street, is an 1883 Queen Anne-style loft built for John J. Clark, a restaurant chain owner.

#38 Lispenard is home to Civil Service Books, a surviving indie bookshop. It apparently once had a much older handpainted sign it has since lost since it moved to Lispenard Street.

Thousands of wannabe Civil Service workers trek to Worth Street in Lower Manhattan to buy so-called exam passbooks, a veritable CliffsNotes for exam prep, at the one store in the city that sells such wares: The Civil Service Bookshop. The mother-daughter outfit has been around for 60 years continuously serving “working people,” as owner Roslyn Bergenfeld said. WNYC.org, referring to its original location at 89 Worth Street.

She Sells the Books on the Civil Service [NYTimes]

I like a place that knows what it is. Barber Shop, #33 Lispenard. I should do a page on the different varieties of barber poles. The red stripe in the barber pole once signified arterial blood and blue, venous blood, as medicinal bloodletting used to be handled at barbershops, which doubled as surgeons during the Middle Ages. Beginning in 1163 in Europe, the clergy was banned from the practice of surgery and barbers took over those practices.

Next to 33 Lispenard. The amazing thing is there are no misspellings.

Church Street comes to its northern end at Canal Street, but not before transferring much of its traffic to 6th Avenue, which runs northbound beginning at Franklin Street.

#9 and #11 Lispenard, which do not fall in the street’s landmarked section and hence, there’s no online information about them. #11 resembles #43 (see above) so, I’d guess it was built sometime in the 1870s.

This is Lispenard Street’s west end, where 6th Avenue meets west Broadway. The building in the center, 39 6th Avenue, is in the new Hilton Garden Inn chain, a reasonably-priced lodging about a block away from the Tribeca Grand, which is unreasonably-priced.

At the NW corner of West Broadway and Lispenard, Nancy Whiskey Pub shares a building with the Pepolino Italian restaurant.

“At the best dive bars, misery and dread are balanced by elation and poorly reasoned optimism. Rot and decay hang in the air, but so does self-affirmation. The patrons and the help relate to each other like dysfunctional family members, bitter and defiant one moment, gentle and supportive the next.” –Ben Westhoff in New York City’s Best Dive Bars, in which he gave it 5 bottles.

This massive behemoth was previously called the AT&T Long Lines Building, though now it’s leased to Verizon, T-Mobile, and other firms. It was built in 1932 by a pre-eminent Art Deco architect, Ralph Walker. The great 27-story height was required to hold long-distance telephone lines. The lobby boasts a world map in mosaic and the ceiling has artwork featuring long-distance telephony to the world’s continents. I’d like to get in there sometime.

See the lobby in the Gallery on the building’s official website.

After leaving Lispenard Street I wandered up 6th to the triangle formed by Laight, Canal, and Varick. For many years this was a forlorn asphalt expanse with nothing at all built there, so naturally, I didn’t photograph it. Of course, now that it’s built up, I can’t do any photographic comparisons.

Capsouto/Cavala Park was developed in 2009 and originally named Cavala Park, but it was renamed the next year for neighborhood restaurateur (Capsouto Freres) and activist Albert Capsouto, who had died in 2010. The centerpiece of the park is a 114-foot-long waterfall sculpture by artist Elyn Zimmerman, which pays homage to the actual canal that once ran long what became Canal Street.

“Cavala” was a whimsical portmanteau combining the first two letters of Canal, Varick and Laight Streets, which the park borders.

For me the most interesting aspect of this park are the stainless steel plaques showing maps of this area throughout history from 1796 on. This map shows the former Collect Pond in today’s Foley Square and the drainage ditch to the Hudson River that became today’s Canal Street. At the northeast section, the X formed by Cross and Orange Streets later became Five Points, the city’s worst slum for much of the 19th Century.

Note at the bottom of the map the smaller body of water called Little Collect Pond. Duane Street was laid out to take a southeast jog to avoid the pond, which was drained long ago, but the bend in Duane Street is still there.

This map from 1803 shows the Collect Pond drainage trenches. Canal Street was not yet fully laid out.

By 1921 the map approximates the modern one, but 6th Avenue was yet to be laid out; it pretty much runs down the middle of this map vertically, from the D in Grand to the Y in York. It was extended south in 1928 when the IND Subway was built.

On the left, the NY Central Freight Depot was replaced by the Holland Tunnel entrance/exit roads in the late 1920s, as well.

This is a reproduction of an 1800 print that shows Broadway extending over the canal where Canal Street would be built. When, in the mid-1910s, Squire Vickers, the pre-eminent subway art director from the mid-teens to 1940, was looking for mosaic designs for the BMT Broadway subway, he chose this print:

This mosaic plaque was designed by Jay Van Everen; the BMT Canal Street station opened 1/5/1918.

The scene is described in Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes‘ New York Past and Present: 1524-1939:

The Arch, or Stone Bridge was probably erected during the Revolution to facilitate access to the fortifications near the Collect Pond. By 1782 Broadway (or Great George street, as it was then called) had been formally extended across and beyond the ditch, clearly indicating the existence of a bridge at this time. The lage double house on the SW corner of Broadway and Canal Street is the “Stone Bridge Tavern” often referred to in writings of he period. The canal ditch ran from the Collect to the North [Hudson] river at Canal Street and to the east river at Catherine Street. In early times it supposed to have been navigable in canoes. It was formalized and a sewer constructed through the street in 1819.

via Lee Stookey’s Subway Ceramics.

You’ll be seeing more of these park lamps around as new parks are built around town. They are used frequently in new parks instead of the classic Henry Bacon Type B post, which was designed by Henry Bacon in 1911. This is officially (to the Department of Transportation) known as the Flushing Meadows pole, despite the fact that they were first introduced in Canarsie Beach Park in Brooklyn in 2004.

Some English and Danish food terms (some in Bodoni Black) have appeared on this building at the corner of Laight Street and St. John’s Lane. Aamanns-Copenhagen, billed as NYC’s first authentic Danish restaurant, will be opening in the space sometime in 2013.

St. John’s Lane, which runs between Beach and Laight Streets west of 6th Avenue, is one of Manhattan’s rare surviving back alleys. Read more about it on this FNY page.

Though it’s one of the busiest streets running south in Tribeca, Varick Street is still paved in Belgian blocks at the Holland Tunnel approach. Colonel Richard Varick was a Revolutionary patriot and later, mayor of NYC from 1789-1801. He was an aide-de-camp to Benedict Arnold but professed ignorance to Arnold’s treason.

Up ahead is One Hudson Square on Canal between Varick and Hudson Streets. It was built in 1930 as the Holland Plaza Building for the printing trades (I interviewed unsuccessfully there in the early 2000s for a job with a printer). Among the current tenants are Adelphi University, New York Magazine, and Getty Images.

One Hudson Square will also be the home of the Jackie Robinson Museum. Robinson, of course, became the first modern-era African-American major league baseball player in 1947 for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and played with excellence for ten years. When he was traded to the New York Giants after the 1956 season, he retired because he had already accepted an offer from Chock Full o’Nuts and his game was beginning to deteriorate from his diabetes.

In the early 2000s the approach roads to the Holland Tunnel were given a set of these unique dual light posts that appear nowhere else in the city.

There’s a parcel bounded by Grand, Canal, Varick and 6th Avenue that has lay empty for a few years now. Apparently the asking price is rather high. For now, you can see the towers of Tribeca from here, including the AT&T tower on 6th Avenue.

Some leftover painted signs on Broome Street just east of Varick.

2012, meet 1870: a billboard for the 2012 James Bond vehicle adjoins Waring’s Building.

With that, it was time for the train.

10/22/12