Dyckman is a big name in upper Manhattan — bookkeeper Jan Dyckman arrived on these shores from Westphalia (then under Prussian control) in the late 17th Century, married into the Nagle family and gradually controlled much of upper Manhattan Island. His descendants were prominent US patriots — the British burned down the original Dyckman homestead at what became Broadway and 204th Street, and his great grandsons built the farmhouse that still stands today.

Street names in Inwood were named for early area settlers such as the Dyckman, Nagle, and Vermilyea families — acre for acre, there are more named streets in Inwood than numbered. Dyckman Street stands in for 200th Street (when the IND Subway was built in the 1930s, its Dyckman Street station on Broadway was given the number 200, but that’s the only place you’ll find 200th Street in Manhattan. And, there’s no 200th Street in the Bronx, either — it’s replaced by Bedford Park Boulevard).

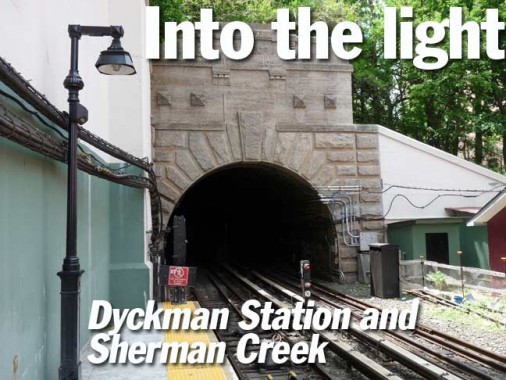

In May 2013, I noted the Parkside Avenue BMT subway station‘s dual nature, partly in a tunnel, partly in an open cut. The IRT’s Dyckman Street station goes Parkside Avenue one better — it emerges from a tunnel onto an elevated trestle.

At Dyckman Street The IRT emerges from, and enters, a tunnel under High Bridge Park inscribed with the title Fort George and the dates 1776 and 1905. Fort George, originally Fort Clinton, was built by US patriots at about where George Washington High School stands at Audubon Avenue and West 192nd Street. Though the British eventually captured the fort, Colonel William Baxter and his Bucks County Pennsylvania militia were able to hold off British general William Howe’s troops long enough for Washington’s troops to escape to New Jersey (much of the Revolutionary War in 1776 in the NYC area consisted of Washington escaping to fight again).

In 1895, entrepreneur Joseph Schenck and his partner, Marcus Loew (later founder of a movie theater chain) opened the Fort George Amusement Park at the end of the old 3rd Avenue trolley line on the old fort site:

During its heyday this Gotham wonderland would boast two Ferris wheels, three roller coasters, nine saloons, a pony track, several hotels, a casino, five shooting galleries, a tunnel boat ride, two music halls called the Star and the Trocadero, fortune tellers and more frankfurters, peanuts and pretzels than you can imagine. My Inwood, which features plenty of photos and postcards of the park

However, as “civilization” crept north to Inwood, the park’s noise became increasingly distasteful and the park came under attack from arsonists, who unsuccessfully tried to burn down the park in 1911, but succeeded two years later. By then Schenck and Loew had sold their interests and went on to the motion picture industry. The site then became part of High Bridge Park.

The “1905” date on the tunnel wall simply refers to the date of construction: the NYC subway, that had begun construction in 1900, arrived in Inwood that year. Compare the extended length of time it’s taking to extend the #7 Flushing Line one stop and the BMT 3 stops on 2nd Avenue. The Dyckman Street station opened March 16, 1906.

There are a pair of blue, green and white tiled Dyckman Street signs on the northbound side. They resemble IND-style signs installed from 1928-1950 or so, but I believe these go back to the station’s 1906 origin. The lettering is the same as what used to be on other station ID plaques found attached to the guardrails, but those have since been replaced by standard MTA black and white stuff:

The older tiled signs had suffered from years in the elements, from the weather to birds, so I’m glad they’re restored as part of the present ongoing (May 2013) renovation of the Dyckman station. Some of the protective cellophane was still on the tiles.

A new set of platform lampposts has been installed. The trend lately is for the MTA to copy former subway lighting schemes, replacing the purely utilitarian models from the 1970s. They follow the pattern of the classic fixtures, which had been mounted on the guardrails as in this 1978 photo.

The new design scheme has even carried over to the utility poles carrying electric wiring.

On the southbound side the station adjoins what resembles an Italianate-style building: an electrical substation, constructed along with the subway (see Joe Brennan in Comments).

Inwood’s streets are almost uniformly lined with multi-unit apartment buildings like these on Nagle Avenue.

Station canopies have been shored up, but the design has pretty much been left the same on the overhead sections.

Around town, new modular walls have been installed on elevated stations that allow for identifying signage as well as openings to the outside world protected by wire screens. Stained glass or other types of artwork can be included too. It’s a lot more esthetic than the old corrugated metal walls that can still be seen on unaltered stations.

Just as the southern end of the station exits/enters a tunnel, the north end is elevated over Nagle Avenue. In between, the station is on a slanted embankment. It’s a very ingenious arrangement — as original IRT engineers had to cope with different elevations, some of the stations are the system’s deepest, some are the shallowest, and in the case of 125th Street, some briefly emerge on a viaduct.

I had heard the Dyckman Street station had reopened after a lengthy period for renovations, but was disappointed to find the entrance was still under construction. I’ll have to return in a year or so to see what it looks like when finished.

This is the embankment portion where the elevated going north begins…

… at the confluence of four streets: Hillside Avenue, Dyckman Street, Nagle Avenue and Fort George Hill.

Fort George Hill is a one-way street ascending a very steep hill in High Bridge Park from Dyckman Street to where it meets St. Nicholas, Audubon and Fort George Avenues at West 193rd Street. It’s a rather tough walk uphill.

The road is one of Manhattan’s oddities. It’s the only street in Manhattan, and perhaps NYC, to be called “Hill,” not Avenue or Street. It has also spent time as 11th Avenue and also as the northern part of St. Nicholas Avenue, as seen on the 1914 map.

In 1962 it was renamed “Fort George Hill,” which was somewhat redundant as there was already a Fort George Avenue.

The upper Manhattan map is a strange beast, as two north-south avenues that don’t get north of West 59th Street resume their courses north of Dyckman Street: 10th Avenue, which runs north to Broadway and West 216th, and 9th Avenue, between West 201st and 208th and again from West 215th to Broadway and the Harlem River. Oddly, the two avenues, which are on the West Side near the Hudson River south of 59th, find themselves on the far east side of the island near the Harlem River here.

10th turns into Amsterdam Avenue at West 59th and runs continuously to Fort George Avenue, which curves to join Fort George Hill at St. Nicholas Avenue. I don’t have the measurements, but it’s likely that 10th/Amsterdam is the longest avenue that travels along the island’s Y axis, beginning as it does at West Street and Little West 12th. 9th Avenue becomes Columbus Avenue, but only goes as far north as West 110th at Morningside Park.

At one time, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th all continued to upper Manhattan as numbered avenues, but beginning in the 1890s city fathers started messing around with the names, as 6th became Lenox, which became Malcolm X Boulevard. 7th and 8th hung in there above Central Park till the 1970s, but then became Adam Clayon Powell Jr. Blvd. and Frederick Douglass Boulevard; 8th became Central Park West along the park, while 10th became Amsterdam and 11th became West End Avenue. For those latter, there must have been a bit of Manhattan snobbery invloved, as the downtowners wanted to differentiate themselves from the uptowners, or vice versa.

In any case I followed Dyckman east to 10th and found a very difficult pedestrian crossing, as the Harlem River Drive dumps its traffic onto 10th and Dyckman here. Fortunately the city has provided a pedestrian bridge.

Entering through a parking lot driveway on the east side of 10th Avenue, I found the semi-naturalized walkway beside Sherman Creek, a short inlet of the Harlem River north of High Rock Park. When I was just starting out FNY when the world was young, ForgottenFan Jon Halabi tipped me off to Sherman Creek, which was marked “marina” on a then-current Hagstrom map. What we found was a yacht graveyard full of discarded ketches and pleasure boats. I wasn’t able to get close up and didn’t have an 18X zoom lens, so the yacht graveyard was recorded only in my mind.

The spot marked “marina” on the old map is currently occupied by a massive Con Ed substation on Academy Street east of 10th, which in fact has been made even more massive the last couple of years.

The short trail along Sherman Creek’s south side affords views of the Bronx as well, including campus buildings of Bronx Community College and the dome of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

Word recently came that the city wants to expand its composting program, but one of the few compost heaps in Manhattan can be found in the eastern part of Sherman Creek Trail. Another compost area can be found in northern Central Park near the Andrew Green Bench — you can tell by the odor.

The creek, as well as Sherman Avenue, are named for a settler family in the early 19th Century about which not much is known. Sherman Creek was originally called Half Kill (the Harlem River was the Great Kill).

Swindler Cove Park is a recent addition to the Sherman Creek public area, found south of the creek along the mighty Harlem and east of the Harlem River Drive.

An oasis of native natural habitats, Swindler Cove features an urban forest, one of the only saltwater marshes on the island of Manhattan’s shoreline and an abundance of wildlife to explore and experience along the Harlem Riverfront. Today, thousands of children from neighboring P.S. 5, other New York City schools and youth from the neighboring New York City Housing Authority’s Dyckman Houses development participate in a wide spectrum of environmental educational programming while using Swindler Cove as an outdoor classroom.

From 1996 to 1999, NYRP removed tons of garbage, rusted-out cars, sunken boats and construction debris from this waterfront site. Then, in 1999 – in partnership with the State of New York Department of Transportation and acclaimed landscape designer Billie Cohen – NYRP transformed the land into a lush array of restored woodlands, wetlands, native plantings and a freshwater pond, accented by a gracious pathway. New York Restoration Project

Has this park really been in place since 1999? Perhaps I haven’t paid attention — I’m not up this way that often.

The Peter Jay Sharp Boathouse, which sits on s a 300-ton barge anchored to the Harlem River bed, was constructed by Robert A.M. Stern Architects (designed to resemble the Central Park Dairy with board and batten styling) and opened in June 2004. Storage for racing shells is provided and the boathouse is the setting for rowing lessons along the river. Offices for the Row New York are also located there.

Additional photos by Nathan Kensinger in Curbed.

Although the city is increasingly using new “Flushing Meadows” poles developed in 2004 for park paths, he 1911 Henry Bacon classic is still in use here; it is augmented with a couple of decorative vegetation hangings.

NYC hopes, eventually, to ring the entire island of Manhattan with bike and pedestrian paths. Some areas will be tough nuts to crack, especially those with Con Ed power installations and the United Nations area along the East River. The path is well established along the Harlem River in High Bridge Park.

Housing projects like the Dyckman Houses, seen here on 10th Avenue, often act as a check against pie in the sky development dreams.

Sign on Academy Street along the north end of Sherman Creek.

My walk today was a little abbreviated. I am on my back to the #1 train at West 207th. The University Heights Bridge, which I’ve written about, is seen in the distance.

If you’re in the area, check out The Famous Jimbo’s Hamburgers at 10th and West 207th. A filling lunch at a nice price. It’s one of a chain in upper Manhattan.

6/29/13