After exploring that odd corner of Queens where every street is named 60, my day wasn’t over. I lit out into eastern Maspeth and got as far as Elmhurst before becoming mad with the relentless, strength-sapping 80-degree heat.

Because it cannot claim a subway line, Maspeth is relatively outlandish territory for most New Yorkers or even novice amateur NYC area urban explorers. It is basically south of Woodside, west of Rego Park, and east of Williamsburg, separated from the latter by the noxious and noisome Newtown Creek. When living in Bay Ridge, I would often launch sorties of exploration by bicycle to far-flung (to me) NYC outposts. I’d call them “Journeys to Adventure” after the 1950s-90s syndicated TV travelogues narrated by Gunther Less which ran for 39 years. (If you remember those, you have a good memory.)

Maspeth was fairly straightforward to reach; I would enter from Greenpoint and then travel south of the cemeteries. I didn’t like to take Flushing Avenue, because until recently, the city didn’t bother to replace the pavement and it was a rattly road for sure. There’s a steep hill between Maspeth and Woodside, and even as a kid, I made it my mission to stay away from hills on a bike. (The exception was Prospect Park in Brooklyn, because a steep northward climb on the east side of the park would be rewarded with a swift downhill run on the west side.)

Of course I was bicycling before it became a political statement and I have never waved the bloody shirt for more bike lanes or bike rentals and whatever else the city is doing the last few years. However, I digest.

This is the route I took on the day’s walk: WAYFARING: MASPETH-ELMHURST

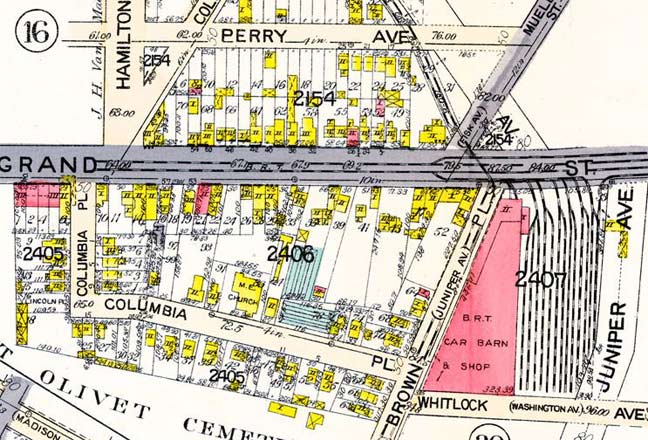

There is an L-shaped route between the intersection of Grand Avenue and Hamilton Place and Brown Place. If you look at old maps, like this one from 1915…

…the whole street was known as Columbia Place. Earlier, or perhaps later, the east-west portion was called Lincoln Place (actually on this map the little dead-end piece on the far left is marked Lincoln Place). These days, it’s 66th Street (north-south) and 58th Avenue (east-west). Also on this map, the Long Island Expressway, which arrived in the 1950s, eliminated the trolley car barns that had formerly been here, and the expressway sheared off Brown Place’s intersection with Grand Street (now Avenue).

I invaded this hidden corner because, except for the occasional occurrences of aluminum siding, these little woodframe houses, many of which have porches, make the street look pretty much the same as it did in 1915, with a notable exception: the Methodist Episcopal Church that served as the block’s centerpiece was torn down several years ago and replaced with modern tract housing, built with low costs in mind.

The many-gabled house at the corner of 58th Avenue and Brown Place, with exquisite detailing on the ground floor and porch, was constructed by Gustav Haflinger, a Maspeth butcher, in the 1880s. Elsewhere around Maspeth, houses that are documented to have belonged to the town’s blacksmith, florist, druggist, etc. can be identified, though some are heavily altered from their early days.

Mount Olivet Cemetery crowns one of Maspeth’s higher hills. From a western redoubt on Eliot Avenue and Mt. Olivet Crescent, the towers of downtown Brooklyn can be seen. The cemetery was founded in 1850 in large part through the efforts of US Congressman and founder of old St. Saviour’s Church James Maurice, whose name is on a major route between Maspeth and Woodside. The cemetery boasts rolling hills and a variety of flora, and was conceived along the lines of then-fashionable “burial parks” such as Green-Wood and Woodlawn Cemeteries. Permanent residents of the cemetery include gangster Jack “Legs” Diamond, boxing champ Tony Canzoneri, cosmetics magnates Helena Rubinstein and Prince Matchabelli, and Maurice himself.

Seen here from Brown Place; main gates are on Grand and Eliot Avenues. The short street zigzags along the cemetery’s northeast side. It was originally a part of Juniper Avenue which later became 69th Street.

Caldwell Avenue begins its run east from 69th Street and Mt. Olivet Cemetery. There’s a building with a tower on the southeast corner that must have been prominent at one time. Anyone know what it was?

Though here it sits in the place of 59th Avenue, Caldwell has never been given a number, because it later turns southeast and intersects several other numbered avenues. Older maps show it as Johnson Avenue. Maps from about 1915 show a street grid here that was never fully implemented, though some of the proposed names, such as Caldwell and Eliot, were used later on.

During my long bike trips to Queens from Bay Ridge beginning in the 1970s I would typically use the Caldwell Deli (which I’m sure used a different name then) at 69th Place for water or juice break. I was surprised to see not much has changed here. it’s still very basic and no-frills, complete with the old pressed-tin ceiling; the place hasn’t been homogenized and 7-11’ed.

From here I would pretty much get to Rego Park or perhaps Flushing Meadows Corona Park before turning around to go home. To do that I would have to go through the Queeens neighborhoods I had just come thorough, then Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Fort Greene, Park Slope, Sunset Park and Bay Ridge, all without a bike lane. Sometimes I’d argue with doorers. I lived.

Caldwell Avenue here enters an area formerly called Nassau Heights, though that name isn’t in much use anymore and many locals call it Juniper Park. At 71st Street, formerly a southern extension of Mazeau Street before the LIE separated it, there is a bend in the road and Caldwell plunges southeast. There’s an odd building with a wood deck on the second door and an elongation on the side. this was probably a former tavern or roadhouse and the long extension likely held a couple of bowling alleys.

I would bicycle east against traffic here. In modern bicycling parlance this is called “salmoning” and is frowned upon. I usually didn’t do it either, but I found Caldwell a nice easy road without much traffic, so I made an exception.

The south side of Caldwell gets along without a sidewalk for a short distance at 71st Street.

Just north of that, the sidewalk reappears, but the houses are built along a different angle from the street; it’s as if there had been a street there, but traffic engineers eliminated it.

I didn’t explore it fully but 75th Street has a collision fence running along its east side. The NY Connecting Railroad runs several dozen yards east of the street, which had recently been repaved in June 2013.

Caldwell Avenue is bridged over the NY Connecting Railroad between 75th and 76th Streets. The railroad is a freight line connecting Brooklyn and Queens to the mainland (Bronx) via the Hell Gate Bridge. It was built during the great flurry of railroad activity in the first two decades of the 20th Century that gave us Pennsylvania Station, the Sunnyside Yards, and the Hell Gate Bridge. The Connecting Railroad ends at Fresh Pond Yards in Glendale, with a collection to the New York & Atlantic, formerly the Bay Ridge LIRR Branch, which ends at the East River in Bay Ridge.

I walked the NY Connecting with the late Bernard Ente and the Electric Railroaders’ Association in 2004, and rode the NY & Atlantic in 2009.

A sample of the attractive attached brick residences that dominate the side streets of Juniper Park. When built in the 1940s, they struck the right balance between utilitarian needs and esthetics. Today, all that green space in the front is considered wasted space by both developers and modern house hunters, who prefer to use the front lawns to park sport-utility vehicles.

Caldwell Avenue Tudor with castle-like cobblestone entrance.

Silver Barn Farms, Caldwell Avenue and 80th Street, is one of Juniper Park/Middle Village’s most popular supermarkets, independently owned for over 40 years.

In 1967 the dairy, Silver Crest, which was located where Walgreen’s is today [one block south], placed outdoor milk machines next to their business. Those machines proved to be very popular with the public. As a result of their popularity, in 1969 the Schwartz family opened a small retail store, which was located on 80th Street, just south of Caldwell Avenue and which operated from 1969 to 1971 and this endeavor also proved to be a big success.

Seeing the handwriting on the wall and the need for a full-fledged retail business, the Schwartz family then bought the property immediately north of their small retail store which was across the street on Caldwell Avenue and in 1971 that move, created the Silver Barn Farms retail store that we have today. Previously there was an A&P Supermarket at that site and back in the day it was a baseball field and, in 1940, the local swimming hole. Juniper Park Civic Association

Nearby, on Eliot Avenue and 80th, is one serious Art Deco building hosting an independent drugstore that seems to be holding its own despite the presence of the giant Walgreens across the street.

The busy 80th Street hosts many attached brick houses, some with especially well-maintained lawns.

When I first began exploring this region by bike in the 1970s, the Pullis Memorial, Juniper Boulevard South and 81st Street, was in sorry shape, but by 1996 the site had been restored and protected.

Though western Queens is well-known for its vast cemeteries, there are also a number of very small ones. The Pullis Farm Cemetery was once the property of farmer Thomas Pullis, who purchased 32 acres in the area in 1822. Pullis prohibited the sale of the cemetery in his will, and it continues to be marked and protected. A memorial marker has replaced the cemetery’s old tombstones.

Juniper Valley Park itself dates only to the 1940s, when NYC acquired 100-acre Juniper Valley Swamp to settle a $225,000 claim in back taxes against gangster Arnold Rothstein, who, it’s believed, had the Chicago White Sox in his back pocket in 1919 when the Sox threw the World Series against Cincinnati. The old swamp is now one of Queens’ most beautiful parks.

Juniper Civic delivers the goods again, with a more detailed history.

Dry Harbor Road is another route that defeats the grid, running between 80th Street at St. John’s Cemetery and Woodhaven Boulevard and Alderton Street and because of that, it too kept its old name. And an unusual name it is. According to NYC Parks, the name goes back to the colonial era: when settlers looked over a valley and saw homesteads there, they looked like boats in a sea of green … a “dry harbor.” (I’m not sure I believe that, but that’s as good an explanation as any.) Hungry Harbor Road in Rosedale may have similar origins.

A bit south of Juniper Valley Park is my favorite street name in Queens: naturally, Juniper Valley Road. The swamp where the park was later built was full of juniper trees, but some maps erred and called it “Jupiter Valley.” One of the streets on the proposed grid I mentioned earlier was to be called “Jupiter Avenue.”

Here’s a close-up of the Tudor at Dry Harbor Rd. and 82nd Street. I’m not sure glass block windows go with a Tudor, but you decide.

1929 map showing the place where Caldwell Avenue ends at Dry Harbor Road. The street grid that would soon be built surrounding the two routes is shown in dotted lines.

Electro-Matic stoplight signal controller, Dry Harbor Road and 84th Street. Here’s a video explaining how they worked.

Leo F. Kearns Funeral Home, Dry Harbor Road and Woodhaven Boulevard. The Kearns family has been in the funeral business for several generations, since Thomas L. Kearns opened a storefront funeral parlor in Bushwick, Brooklyn in 1900. Thomas’ son, Leo, began a funeral business in Ozone Park in 1926; he was later joined by his brothers, and the Rego Park funeral home shown here opened in 1955.

Roman Catholic Resurrection-Ascension Church, 61st Road off Woodhaven Boulevard. The church was instituted in 1926, with the cornerstone for the present church-school combination building laid in 1938. The name honors Roman Catholic tenets that hold that Jesus Christ arose on Easter Sunday after His crucifixion on Friday (Resurrection) and was taken bodily into heaven later (Ascension).

True to my usual practice I was attracted to the various letterforms found on the building, most in a serifed ecclesiastical tradition; in a more ornate form, this kind of lettering goes back to medieval texts like the Book of Kells.

Two figures holding banners, likely pertaining to the Resurrection and Ascension, are mounted beside the front entrance. Since they are not bearded, they are likely angels and not Christ himself.

(I wonder why there has never been a traditional rendering of Christ without a beard.)

More lettering at the front and auditorium entrances.

Fast and furious 8-lane Woodhaven Boulevard runs from Queens Boulevard at the Long Island Expressway south to the Rockaway peninsula, changing its name to Cross Bay Boulevard at Liberty Avenue. It could never be guessed from its modern-day roaring traffic, but when it was first traveled in the mid-19th Century it was a bucolic two-lane cart path called Trotting Course Lane, since it led to racetracks in Woodhaven such as Union Course.

Similar to what was done with Brooklyn’s Kings Highway in the 1920s, in that decade traffic engineers, sparked by the popularity of the auto, widened Trotting Course Lane into the present 8-lane behemoth.

60s attract: old pals 60th Avenue and 60th Place intersect at Woodhaven Boulevard again, as they did in western Maspeth (see link at top of page).

I’ve discussed the giant Elmwood Theatre neon sign on Queens Boulevard ad infinitum — the sign is still there even though the theater is now a church — but if you walk around to the back of the theater, on 57th Avenue, there’s this painted sign with nice serifs.

Quiet Seabury Street now is home to one and two-family residences, but I have old photos showing large estates there that have all vanished. This is the parish house for the First Presbyterian Church of Newtown (see below). The brick building was constructed in 1931. It is also an Elmhurst HQ for South Asian Youth Action.

Here’s a handsome Federal-style house on Seabury Street and 54th Avenue. Under the entrance pediment you will find an etched glass sunrise motif.

First Presbyterian Church of Newtown, Queens Blvd. and 54th Avenue:

This congregation dates back to 1652. Rev. John Moore (whose descendant, Clement Clarke Moore, penned the poem, “The Night Before Christmas”) was the first minister of the congregation. The church was involved in the signing of the Flushing Remonstrance, which was instrumental in establishing freedom of religion in the colonies. The church building has had many incarnations. The current Gothic style brownstone and granite structure was built in 1895 with $70,000 left to the church in the will of one of its elders. The architect was Frank A. Collins. The cornerstone, laid in 1893, contains a time capsule. Juniper Civic

When the church was built, Queens Boulevard was still the 2-lane Hoffman Boulevard, and when the road was widened to its present width in the 1920s the church had to be picked up and moved back several yards.

I always include the church signboard, if it’s old-fashioned enough.

Elmhurst’s World War II memorial stands in the front churchyard.

ForgottenTours have met at The Georgia Diner for at least two postgame shows. The neon sign features a peach. The circular Macy’s Department Store and parking garage can be seen in the rear.

Yelpers rank it 3 stars in general.

7/21/13