This all got started with a screen capture from Forgotten NY correspondent Sergey Kadinsky, who sent me a photo of a strangely-named Queens street and asked me if I knew where it was. Of course I knew, but it was a neighborhood I hadn’t been in for over a dozen years, the one just across the subway tracks from Kennedy Airport formerly called Ramblersville but now referred to as West Hamilton Beach. It’s built on the swampy and saturated ground surrounding old Hawtree Creek, which has been tamed into a canal — but tends to leach out after a heavy rain and flood the streets.

Mapmakers have always had a difficult time depicting the area accurately, since it’s a semiprivate area. When I was in there in 2000, I felt like plenty of sets of beady eyes were on me. Bespectacled, baseball-capped grotesques prowling about with cameras are not often seen in this area, considered remote by all but its residents. It’s likely that throughout the decades, other surveyors have experienced the patina of hostility as well, and so West Hamilton Beach (I always think of blenders when typing the name) doesn’t really show up on commercial maps as it really is (this has also happened in semiprivate areas like Riverdale and Harding Park in the Bronx). There had been a Hamilton Beach settlement east of the tracks, but it was cleared out when airport construction began in the 1940s.

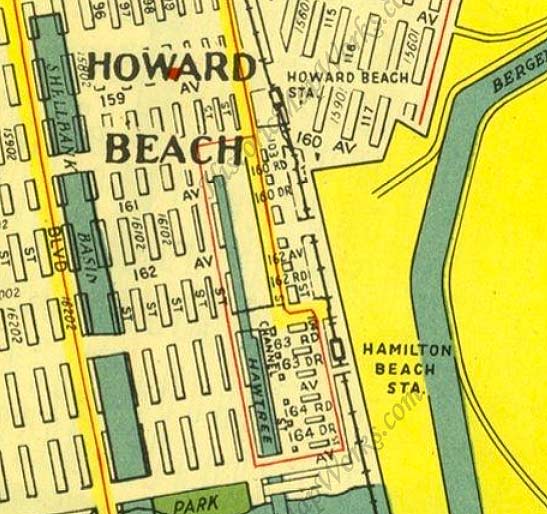

West Hamilton Beach, is west of the LIRR Hamilton Beach station shown here on this 1949 Hagstrom map. (The station, just a shack and a clearing by the tracks, closed in 1955, and the line was then purchased by the Transit Authority and converted to the NYC subway system.) The vertical road by the tracks and the intersecting dead end streets provide a generalized idea of the street layout, but the depiction of Hawtree Creek without a tributary is completely wrong. Note the bridge shown at 165th Avenue at the bottom — we’ll get back to that.

West Hamilton Beach in 1924, left, and in 1966, right. The neighborhood is west of the vertical line of the railroad tracks in both photos. (The image is covered with watermarks as a reminder that I’m not supposed to be using it like this.) As you can see, Hawtree Creek or Basin has a pair of tributaries that affect the street grid. Only maps produced in the last 30 years or show depict it. As such overhead views became more greatly disseminated on Google views, etc. mapmakers had to get more realistic when showing this area. And thus…

… Google, on both its satellite and map views, can now depict West Hamilton Beach as it truly is. It’s a small settlement squeezed between the subway tracks and Hawtree Basin, quite true, but there’s a distinct separation caused by the two small channels, or tributaries, that the basin gives rise to. The common road between the two is 102nd Street, which is bridged across the northernmost one by the Lenihan Bridge (see below) and then another road, Russell Street, carries traffic, including the Q11 bus, which runs down Woodhaven and Cross Bay Boulevards from Queens Plaza and has a complicated route down here. In effect, there’s a North West Hamilton Beach and South West Hamilton Beach, though nobody refers to them as such.

To access this remote settlement (by neither car nor boat) you take the A train of lore and song south to the Howard Beach station, originally a bare bones LIRR stop that was adapted for the subways in 1956 and then extensively modernized in the early 2000s with the arrival of AirTrain, an express rail system to the JFK Airport terminals. Prior to AirTrain, a shuttle bus rattled through the parking lots and eventually got you to your terminal, hopefully in time to catch your plane. (more photos of the station throughout its history available at the link.)

The small cluster of streets surrounding the Howard Beach station are known as Coleman Square and constitute the area’s main shopping and dining district, though most residents have cars and prefer to travel west to Cross Bay Boulevard to meet such needs.

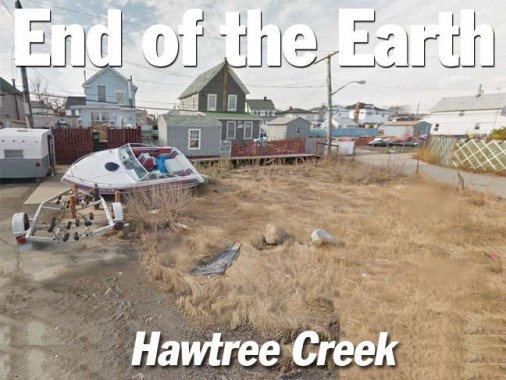

By the way, I got the photos for this page from Google Street View and crudely edited out the street names depicted on the shots, though not in this case.

Hawtree

A number of streets and bodies of water in southern Queens are called Hawtree this or that: Hawtree Basin, Hawtree Avenue, Hawtree Street, and Hawtree Creek Road, a very old road in south Jamaica that originally led to the creek. “Hawtree” is an old word for “hawthorn” as in the tree, and we can surmise that there were plenty of hawthorns around when European navigators first surveyed and mapped the region in the early to mid-1800s.

This 1909 map shows pretty much nothing yet built in this area, save the railroad, which arrived in the 1860s, and a few shacks along the creek near where the railroad bridged over it. However, property lines had already been diligently divided up. Note the name “Wm. J. Howard.”

Howard Beach was established in the 1890s by William J. Howard, a Brooklyn glove manufacturer who operated a 150 acre goat farm on meadow land near Aqueduct Racetrack as a source of skin for kid gloves. In 1897, he bought more land and filled it in and the following year, built 18 cottages and opened a hotel near the water, which he operated until it was destroyed by fire in October 1907. He gradually bought more land and formed the Howard Estates Development Company in 1909. He dredged and filled the land until he was able to accumulate 500 acres by 1914. He laid out several streets, water mains and gas mains, and built 35 houses that were priced in the $2,500–$5,000 range. wikipedia

Most of the area collectively known as Howard Beach would remain marshland until after World War II when the familiar suburban tract houses lining the grid pattern streets were built. Even they have a precarious existence, as the entire region was severely flooded by Hurricane Sandy in October 2012.

South of Howard Beach, 102nd street crosses a few oddities:

Broadway

Broadway looking east from 102nd Street

All five boroughs have a Broadway (the Bronx Broadway is a continuation of the Manhattan Broadway) but Queens is blessed with two. However, the West Hamilton Beach Broadway is a far cry from the Great White Way, or even the other Queens Broadway, which runs from Astoria to the heart of Elmhurst. This Broadway is lined with modest one-family houses and seems to be frequently flooded.

The intersection of Broadway and Bridge Street, proceeding north from Broadway east of 102nd Street.

West of 102nd Street Broadway comes to a dead end at Hawtree Basin. Many families in this area own boats, as you might expect, and vessels of several sizes and makes can be seen along the side streets and in accompanying yards.

Church Street is a short dead-end leading north from Broadway, west of 102nd Street and paralleling it.

Ramblersville-Hawtree Memorial Bridge

The 102nd, formerly Lenihan, Bridge carries traffic south over a Hawtree Basin inlet into West Hamilton Beach.

Sergey Kadinsky:

On the northern side of the footbridge, Hawtree Basin splits into three branches, the longest originating near the train tracks. The only road linking West Hamilton Beach to mainland Queens is 102nd Street, which crosses the northernmost branch of the inlet using a short and narrow. It is likely the shortest automobile-accessible crossing in the city with an official name. For much of the 20th century, it was known as Lenihan Bridge, named after local Alderman John Lenihan, who served from 1924 to 1935. He was remembered in his time for promoting transportation to the isolated enclave. In 1967, the City Council made the bridge name official.

The narrow bridge and its neighboring dead end roads often appeared in newspaper accounts as a traffic hazard. In October 1914, the New York Times reported on the death of motorist George Greenburg and passenger Rose Graber, who were traveling to Far Rockaway from their Brooklyn homes. Making a wrong turn into West Hamilton Beach on a rainy night, he drove off a bulkhead into the water. The vehicle rested in eight feet of water. Investigators found an open knife and a cut on the car’s tarp, suggesting a failed struggle to escape the drowning.

In February 1952, Queens resident Charles Langenfeld of Richmond Hill and Charles Haag, Jr. of Howard Beach drove their convertible through the wooden bridge railing, drowning in Hawtree Creek. The bridge was narrow, short and had a sharp turn at its southern landing.

Prior to 1995, West Hamilton Breach was one of a handful of neighborhoods in the city that was not connected to its sewer system and all residents had to rely on private cesspools to store wastewater. The much-anticipated installation of sewers required a controversial replacement for Lenihan Bridge in order to accommodate trucks carrying construction materials. Augustine Barry, a homeowner whose property abutted the bridge, opposed the project because a temporary bridge would be placed within four feet of his home. For Mr. Barry, the project smacked of injustice as he had moved to West Hamilton Beach 40 years earlier after his prior home was demolished to make was for the Long Island Expressway in Elmhurst. Apparently for his family, relocating to this isolated enclave could not keep him safe from the city’s power of eminent domain.

The construction of the temporary bridge resulted in cracks on the foundations of Barry’s home. Diesel exhaust from passing buses added to the aggravation. In June 2006, the city’s Department of Buildings declared the home unsafe, ordering Mr. Barry and his wife Ann to vacate. The city’s chief engineer, Robert J. Rohayne offered his Brooklyn apartment to Barry, but it was turned down. He chose to sleep in his car instead, in order to guard the home and its chickens from potential vandalism.

The story had a happy ending a year later. ”All’s well that ends well,” said the city’s Transportation Commissioner, Christopher R. Lynn. The city repaired the home to a tune of $455,000. Estimating the cost of the house at $150,000, Mr. Barry was pleased to move in but felt sorry for the taxpayers who footed the bill. As his brother Eugene summed it up, “”All’s well that ends well, sure. But this all could have been avoided.”

A final chapter in this bridge’s saga is the change in name for the bridge. In 2001, Lenihan was long forgotten and the crossing was renamed Ramblersville-Hawtree Memorial Bridge to honor seven soldiers from the neighborhood were killed in the Second World War.

Russell Street also comes to a dead end at Hawtree Creek. However, east of 102nd Street it is the only connector to the main street of the southern section of West Hamilton Beach, which is…

… 104th Street, which runs alongside the A train, formerly the Long Island rail Road Rockaway Branch.

Several dead end streets emanate west from 104th Street and, until fairly recently, I thought they all had number names, such as 163rd Avenue, Road and Drive, 164th Avenue, Road and Drive, and so on. However, back in the 1970s, Hagstrom maps began to list different names for a couple of these streets, and riding past on the subway, you saw different names on the signs, as well.

First Street (which is spelled “First” on the street sign, not “1st”) is the only diagonal street in the neighborhood, running from 104th southwest to Rau Court (see below). This makes three streets in Queens named “First” or “1st,” all of them quite short: 1st Street in Astoria, which runs from 26th Avenue to just past 27th, at Astoria Houses near the East River; 1st Street in Meadowmere, the very last bit of Queens as you are traveling south on Rockaway Boulevard before attaining the Five Towns (it is accompanied by 2nd and 3rd Streets) and First Street, here in West Hamilton Beach, which stands oin its own, unaccompanied by a Second Street.

Far away, in Gravesend, Brooklyn, there’s also a First, or 1st, Court off Coney Island Avenue, without any other similar numbers. South of that, there had been a 1st, 2nd and 3rd Places in Gravesend, and they’re gone for over 75 years — but can be seen on old maps.

Dunton Court, south of First Street.

Rau Court, which along with First, is the only street west of 104th that doesn’t dead-end. The pedestrian bridge from Howard Beach crossing Hawtre Creek (see below) also empties onto Rau Court.

I have a feeling the name is pronounced to rhyme with “how”, because a 1970s Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher named Doug Rau pronounced his name like that, though I could be wrong. (Rau wasn’t well-known or a superstar by any means, but his statistics today would probably earn him a multimillion dollar contract.)

Doug Rau argues with Tommy Lasorda during the 1977 World Series

Davenport Court stands in for 163rd Avenue. The West Hamilton Beach Volunteer Fire and Ambulance Corps headquarters is located on the corner of 104th Street. Established in 1928, the Corps celebrated its 85th anniversary of service in 2013.

The original quarters was a house located on the same lot where the current building stands. It was converted into a garage which would be come the firehouse. Through the years many changes were made due to the variations in apparatus. The original building stood until 1992 to make way for the new building due to an unsound foundation. During construction the quarters was relocated into a trailer which still stands on the property and is in use by a non for profit organization.

The current quarters stands two stories high and is divided into two different apparatus bays. The fire bay has one door and fits two fire apparatus side by side. Firefighter gear, work bench, battery chargers as well as spare SCBA bottles are located in the fire bay. Best access to the fire bay from the second floor would be via the original pole from the original firehouse. The ambulance bay also fits two EMS apparatus side by side but each vehicle has its own bay door. Also located in the ambulance bay is a backup generator, EMS storage, equipment storage, a restroom and a mess sink. On the second floor, we have a bunk room with three bunk beds, an officers office, house watch, full size bathroom, kitchen, lounge and meeting room. HBVFD

Sergey Kadinsky:

In October 2012, Superstorm Sandy caused extensive damage in the neighborhood, resulting in the loss of all but one of the ambulances belonging to West Hamilton Beach Volunteer Fire Department. Within a year, the department raised funds and received donated vehicles, increasing its fleet to nine vehicles comprising of five ambulances and four fire trucks.

Burlingame Court is identified by a relatively new sign accompanying the one identifying it as 163rd Road. The names are apparently interchangeable. Area residents, let me know which street name is preferred on these side streets — the number, or the name?

James Court, or 163rd Drive.

164th Avenue has retained the name, though the official Department of Transportation street signs must be relatively new — many of these dead ends have amateur signs with the street number scrawled on them nailed onto telephone poles!

164th Road, a.k.a. Calhoun Court.

At 164th Drive/Moncrief Court, heavily protected by barbed wire, is an MTA substation, containing electrical relays for the third rail accompanying the nearby A train.

The DOT capitalizes the C in Moncrief on the street sign, but that’s probably an error. The name reminds me of Sidney Moncrief, the Milwaukee Bucks’ 1980s star basketballer.

Lockwood Court, or 165th Avenue, is the last dead-end along the strip. All the numbered avenues continue west of Hawtree Basin in Howard Beach, and 165th Avenue is the highest numbered avenue in the sequence (the lowest is 2nd Avenue, which consists of a couple of dead ends in Whitestone.)

As Sergey explains, 165th Avenue used to run directly into Howard Beach via a traffic bridge over Hawtree Basin, but no longer:

Prior to 1963, West Hamilton Beach had a second automobile connection with Howard Beach at 165th Avenue, also known as Lockwood Court. The bridge was a notorious traffic hazard, resulting in the death of a local motorist in 1956. A year later, the city banned buses and trucks from using this bridge, described in news reports as “decrepit.”

It was replaced in 1963 with the present Hawtree Basin Bridge (above), a pedestrian crossing in the form of a bright blue arc across the channel at Rau Court.

As global weather patterns suggest an increase in large storms, environmental and urban planning groups proposed a combination of manmade and natural barriers to mitigate storm surge damage. The natural element involves introducing reefs and marshes to serve as sponges in absorbing massive waves. The manmade element is inspired by existing examples in the Netherlands, where movable barriers are located at the mouths of streams. In this case, barriers installed at the mouths of inlets along Jamaica Bay would keep storm surges away from homes along the shore of Hawtree Creek and Shellbank Basin.

12/22/13