Though I had been in Flushing repeatedly (for Mets games and to visit my friend Gary) it wasn’t until 1993 that I got more intimately familiar with the neighborhood, as I moved there to get closer to a job in Port Washington, Nassau County. My building was a few blocks away from the Long Island Rail Road station FNY is taking a look at today — the (to some) inexplicably named Broadway station. While all boroughs have a Broadway — Manhattan and the Bronx share theirs — Broadway in Queens runs from the East River at the Socrates Sculpture Park on Vernon Boulevard straight to the heart of Elmhurst at Queens Boulevard. All this, of course, is miles to the west of fab Flushing. Yet here the Broadway LIRR station sits. How can this be?

Until about 1920, all of Northern Boulevard from the Flushing River to the city line in Little Neck was named Broadway. West of the Flushing River, Northern Boulevard was known as Jackson Avenue, because it was built as a toll road by John Jackson in the 1850s from the waterfront through Astoria, Woodside and the Trains Meadow area now called Jackson Heights. East of the Flushing River there was an already-existing trail that had likely been used by Native Americans for centuries prior to the incursion of the white man. The road connected Flushing as well as the farms and fields east of it as far as Roslyn, and sometime in the 19th Century, it acquired the name “Broadway.” East of what would become the Queens-nassau county line in 1898, it was called the North Hempstead Turnpike, which made sense, since it ran through the town of North Hempstead, originally in Queens, later in Nassau.

The above map is from 1909 and shows the LIRR Port Washington line as it runs through the area. I’ve inserted ‘modern’ street numbers on a couple of the streets, which were originally numbered from 1 to about 30 in Flushing, but were renumbered as Queens acquired a single overall street numbering system beginning in 1915. Both Crocheron Avenue, named for a local landowning family, and Sanford Avenue, named for US Senator Nathan Sanford (1777-1838), who resided in Flushing, have kept their old names.

The first family member to live in the area was John Crocheron, a farmer whose will dates from 1695. His long line of distinguished descendents include: Henry Crocheron, a Congressman from 1815 to 1817; Jacob Crocheron, a Congressman from 1829 to 1831; Nicholas Crocheron, a member of the 1854 State Assembly; and Joe Crocheron, a horse racer and gambler who was as renowned as Cornelius Vanderbilt and August Belmont. NYC Parks

Crocheron is another one of those NYC names, like Joralemon and Cortelyou, which have tricky pronunciations that could be considered counterintuitive. As far as I know, it’s correctly pronounced “CRO-sher-on.”

Above: Rickert-Finlay office building, Northern Boulevard and 162nd Street, in 2013

You can see the name “Rickert-Finlay Realty Company” on the above map. In 1906 the developers set about building up vast swaths of northeast Queens, from Flushing to Little Neck, as the former farmland became residential property. The anticipated opening of the Queensboro Bridge (1909) made the heretofore sleepy county ripe for new residents. The immediate area became known as Broadway-Flushing, and the region north of the railroad that was developed by Rickert-Finlay remains some of the most exclusive and beautiful neighborhoods in New York City. Longtime area residents, whose houses still adhere to the Rickert-Finlay Covenant of 1906 restricting what types of houses can be built in the area, have battled tooth and nail with new residents and immigrants, who want to build their preference of houses. Who comes out on top will determine whether Broadway-Flushing retains its century-old flavor.

The Broadway station achieved its present condition in 1913 when the grade crossings on 22nd Street (now 162nd Street) and Broadway (Northern Boulevard) were both eliminated. It was quite an involved operation. To do this, the tracks had to be placed on an embankment and, east of about 165th Street, an open cut, an elevated bridge in Auburndale and another open cut in Bayside, as the contours of the territory differed greatly. That wasn’t the only thing that had to be done, though. Both 162nd Street and Northern Boulevard had to be extensively excavated and an artificial slope constructed so that traffic had at least 1 ten-foot height to pass under the embankment, which was placed on a concrete and iron trestle.

Above is a 1920s postcard look at Depot Road just east of Northern Boulevard. Two streets named Depot and Station Roads accompany the railroad for several blocks in the area. Not a great deal has changed since the postcard was produced. The pedestrian entrance seen on the right was restored to service in 2007, and the two station buildings as well as the 3-story multiuse building on the left are still there, too. The right side of the photo, under the trestle, has been occupied by a florist for several years.

A Google Street View shot from the recent past shows that the center median has disappeared with the right side used for parking. The buildings on the left must have been built just after the postcard was produced.

This is a postcard made in 1907 showing the north side of the Broadway station facing Depot Road. As you can see, runabouts were easily able to pull up trackside and deposit passengers. In the background you can see some of the homes lining the north-south streets in Broadway-Flushing. At this time the line still ran at grade (on the surface) and was still single-tracked.

What’s now the LIRR Port Washington Branch was built by the Flushing Railroad in 1854 and was extended as far as Great Neck by 1866. After a series of mergers and acquisitions, the Long Island Rail Road had acquired the branch by 1875. The line was extended to Port Washington in 1895.

The 3-story apartment building seen in the postcard still stands on Depot Road, facing what is now the westbound track of the railroad. More on Depot Road below.

Looking north on 162nd Street toward Northern Blvd. The elevated trestle across both 162nd Street and northern Boulevard has been recently completed, with massive concrete pillars holding up the trackbed. Now the roadbeds on both streets are being depressed under the overpass. gthis entailed the complete replacement of the water mains and other pipes. When complete 162nd Street would run to the left of the pillar in the center of the photo. The Broadway station is off to the right of the picture.

The scene from about the same location looks like this about one century later. 162nd Street developed into the main north-south shopping street. Buildings went up on both sides of the street shortly after it was directed underneath the LIRR overpass.

This is 164th Street looking north across the tracks from just north of Northern Boulevard in 1913. Here, the railroad has remained at grade with the street, but the crossing has since been eliminated. There is a pedestrian underpass in this location now. Only the handsome Broadway station building is the same today, and it, too, has been altered somewhat. To the right of the photo, the Broadway-Flushing post office, which was never given a name and is still called “Station A” was built some decades later.

By the 1920s the crossing would look like this. A passenger crossunder was built beneath the tracks. The station featured pebbled concrete railings and when I first encountered it in the 1990s, bolts that held iron station lamps in place could still be seen. I have more views of the “old” Broadway station before renovations below.

After extensive renovations completed in 2007, the crossunder looks like this. The red windows shelter a wheelchair ramp that connects to the crossunder. You can see the roof of the station building in the background.

When I first started boarding the LIRR from this station in 1993, it was in a state of disrepair and by the early 2000s had begun to literally crumble away. In fact much of the westbound platform had to be closed because it was tumbling down onto the tracks. Sometime in the 1960s the platform had been extended east to service up to 12-car trains, and that portion of the platform was in good shape. Except for new railings and lighting, it was left alone. It was a good thing it had been built, because, as we’ll see, the older portion was simply jackhammered into oblivion and a completely new one built.

Before renovations, the Broadway station featured an interesting curio from the LIRR’s salad days: a separate “house” that served as a waiting room on the eastbound side. By the 1990s, it was reduced to serving as a urinal for local vagrants and youth, and was unceremonially demolished in 2006. On the westbound side, a simple lean-to served as a bench. However, on that side the station house gave adequate shelter because even though the ticket office was closed most of the time, you could get under the eaves during rain or snow. That feature is still there. The LIRR has also installed metal seats, but they do get pretty hot in summer.

I got this photo in 2006. At this point the station house renovations and improvements had just been finished. However, you can see the decrepit condition of the platform, and a complete transformation was in the offing.

Thus the MTA completely destroyed the old part of the station to the last stone, and built new pilings and platforms. While doing this, the renovated station house’s windows were boarded up so no cracks could develop. The eastern end of the station that was built in the 1960s filled in yeomanly but for about a year, you had to enter in the rear of the train.

The second photo shows the reconstruction as well as the old platform on the left, that would in turn also be replaced.

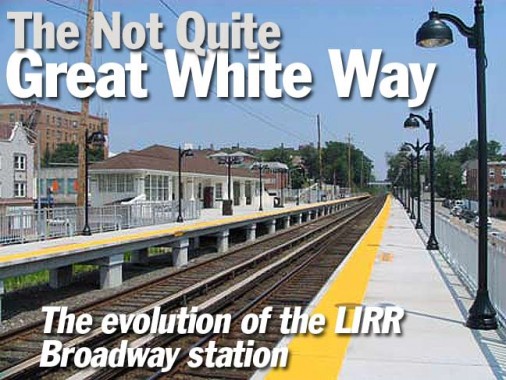

So, during my entire tenure using the Broadway station, 1993-2007, I dealt with a crumbling, decrepit structure that cast shame upon the greatest metropolis in the country. After I moved to Little Neck, Broadway was transformed into a state of the art suburban rail station, with new lighting, handicapped access, public address, railings and shelters.

Broadway also participated in the MTA’s Arts for Transit program, with the installation of Jean Shin‘s “Caledon Remnants” which appears on the stationhouse as well as sprucing up the old concrete entrance stairs first installed after the grade cross elimination in 1913:

Fragments of traditional Korean ceramics are arranged into mosaic murals of vase silhouettes on the façade of the Broadway Long Island Railroad station in Flushing, Queens. Located in the heart of a vibrant Korean-American community, the abstract, green-blue silhouettes enhance the beauty of the Celadon itself, while the overall piece speaks to the rich, yet fractured, cultural history of the Korean diaspora. The pottery remnants were imported from Icheon, Korea as part of a cultural exchange. Jean Shin

Depot Road, along with 162nd Street, was originally the first urban center in the area and features some interesting architecture. This Flemish-style stepped building at 164th Street is mixed-use with apartments and a ceramics studio on the ground floor.

This mixed bag of architectural forms featured now-stopped up dormer windows. The houses were likely built in the 1920s.

A lengthy wheelchair access shelter was built during station renovations in 2007.

Depot Road looking west toward Northern Boulevard.

This ceramic sign inexplicably survived for decades at the Depot Road Manhattan-bound entrance steps. The MTA had completely forgotten about its existence and left it in place …

..until the renovations, when it was replaced by standard signage. I hope the old one has a place of honor in someone’s collection.

Some photos courtesy Bob Andersen of LIRR History and Victor Annaloro.

2/9/14