As you can see on this Dripps Atlas plate from 1867 (zoom in for a closer look) , in the ‘beginning’ there were nine streets that ran up the Lower East Side, parallelling the East River all the way to Corlears Hook… South, Front, Water, Cherry, Monroe, Madison, Henry, East Broadway and Division. These streets, as well as their cross streets, Catharine, Market, Pike, Rutgers, Jefferson, Clinton, Montgomery, Gouverneur, Scammel, Jackson, and Corlears, were jam-packed with cold-water tenement houses, all of them filled with families — making the Lower East Sde one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in Manhattan.

Beginning in the 1930s, the grid was interrupted as large “towers-in-a-park” housing projects were built, one by one — the Al Smith, LaGuardia, Rutgers, Vladeck, Knickerbocker, Corlears Hook Houses. Entire blocks were eliminated and, in some cases, entire streets, such as Oak, Front and Scammel, and some streets such as James and Monroe were reduced to a block or two. (It’d be fun to create a Random Name Generator of the neighborhood, since you can get famous names like Henry James or James Monroe. )

One street, though, seems to have preserved much of its old tenement flavor, Henry Street, which along with Rutgers Street was named for Revolutionary-era soldier and wealthy landowner Henry Rutgers. I walked the entire length of the street during a brief time in the winter of 2014 when the temperature edged above freezing and the glaciers retreated.

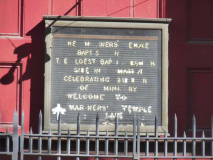

Henry Street’s entire length has been preserved from Oliver Street northeast to Grand Street at Lewis. The first prominent building to be seen is the Ionic-columned Mariners Temple Baptist Church — a very old church, but not Henry Street’s oldest. The Mariner’s Temple was built in 1845, though the parish, serving a congregation of sailors and maritime workers and their families, goes back to 1785; there has been a church in this location just about since the streets themselves were built just after the British colonial era ended. The cornerstone of the first church on the premises has been preserved and can be seen above the front entrance.

As maritime activity shifter to the deeper waters of the Hudson, the early Church continued its ministry and gained an additional name, “The Mother of Churches.” As Swedish, Italian, Latvian, Russian, and Chinese immigrants moved through the Lower East Side, Mariners’ gave life to the first Swedish, Italian, Russian and Chinese Baptist Churches, as well as the Norwegian-Danish Mission of New York City…

From the middle to the late 1900s, Mariners’ Temple continued to be a spiritual center for all ethnic groups in the neighborhood. In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Mariners’ reached beyond the spiritual realm to address the political needs of the community. Locally, there was picketing of low-income housing thought to be urban removal rather than urban renewal. Nationally, Mariners participated in the famous “March for Jobs and Freedom” held in Washington, D.C. in August 1963…

By the early eighties, the congregation was mainly Chinese and African-American, with separate services held for each. Later, the Chinese congregation moved into its own church in the area. In May 1992, the congregation paid off the mortgage on the church building and celebrated the title transfer from the American Baptist Convention/Metro NY to the Mariners’ Temple Baptist Church congregation.

Today, there are two unique congregations at Mariners’: the Sunday morning congregation and the congregation from Lunch Hour of Power (LHOP), which was established in the 1980s under the pastorate of Rev. Dr. Suzan Johnson Cook. The LHOP congregation, which is comprised of government and corporate employees in the surrounding area, worships at noon on Wednesdays. Mariners Temple Baptist Church

Across Henry Street from the temple is another venerable edifice, PS 1, the Alfred E. Smith School, named for the “Happy Warrior” NYS Governor who grew up in the neighborhood as a boy. It was built in 1897 as Grammar School No. 1.

Henry Street looking northeast from Oliver Street

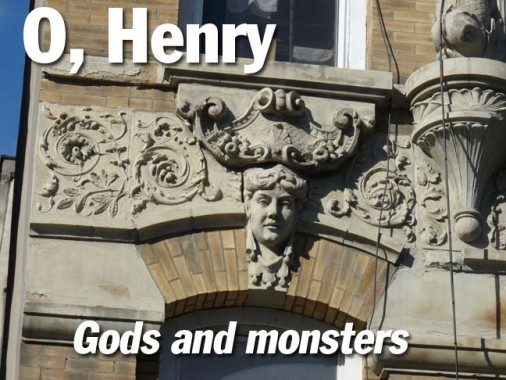

#39, 41 and 43 are an interesting trio of tenement buildings on Henry Street. 39 and 41 are a matched pair, still with their original scrolled iron railings. A bearded paternal head (Zeus?) overlooks the front door, flanked by two female busts. Shouting bearded figures appear below pedestals on the third floor windows.

#43, meanwhile, in brilliant red brick with green cornices and white trim plus the word “Manhattan” at the roofline has cherubic figures on the pilasters at the front entrance. A roaring feline-appearing monster guards the keystone above the entrances, while other roaring creatures appear on both sides of each floor above the first.

At the SW corner of Henry and Market Streets is what was originally the Georgian Market Street Reformed Church, which was built in 1819 — it will celebrate its 200th anniversary soon. The windows are made up of multiple panels –35 over 35 over 35. This is now the First Chinese Presbyterian Church, which shared the building with the Sea and Land Church until 1972.

The brick and stone Georgian-Gothic church at 61 Henry Street was built in 1817-19 as the Market Street (North) Reformed Church on land donated by Colonel Henry Rutgers. In 1864, the Dutch Reformed Church disbanded. The church building was then bought by Hanson K. Corning in 1866 and it was transferred to the Trustees of New York Presbytery to be occupied by the Church of Sea and Land which served the seamen community in the area. In 1951 the First Chinese Presbyterian Church moved to its current location by sharing the building with the Sea and Land Church. The Sea and Land Church was dissolved in June of 1972, and in 1974 the Presbytery transferred the building as a gift to the First Chinese Presbyterian Church. In 1966, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated both the church building and its Erben pipe organ to be historic landmarks. The church building has the distinction of being the second oldest in New York City. NYC Organ Project

Pike Street is a southern extension of Allen Street (which in turn transfers its traffic to 1st Avenue at East Houston Street. When Allen Street was widened and given a center median in the 1930s, the median was extended south on Pike Street, which becomes Pike Slip near the East River to commemorate its former life as a docking slip for vessels. Pike’s Peak in Colorado, as well as this street, is named for missionary and explorer Zebulon Pike. He was killed in 1813, fighting the British in Canada during the War of 1812.

According to NY Songlines, the Sung Tak Buddhist Association at 13 Pike Street was once

the Pike Street Synagogue, a Classic Revival building from 1903 that housed the Congregation Sons of Israel Kalwarie. Eddie Cantor was bar mitzvahed here in 1905.

This is the northeast corner building at Pike and Henry. Once again, a large amount of festoonery, prominent cornice, large window lintels, and a sheltered entrance. A goddess (Cybele, perhaps?) presides over the entrance, but above her on the second floor is a snarling beast. What do these mixed messages mean?

There’s a lot going on at #111 Henry next door. A pair of sullen beasts guard the front door, but their vigilance is tempered by a pair of potted flowers on the pilasters. Two goddesses overlook the second floor windows, while a pair of wriggling fish appear beside the third floor windows. Note how the window treatments are different on every floor. Finally, a green man can be seen just under the cornice on the roofline.

At #117, the front stoop railing and bannister are still in place, though they need paint. Time has worn down the presiding god or goddess above the door to a rather simian appearance.

Why all these human heads and gods above the entrances? My guess is that they are supposed to represent the Roman tradition of lares and penates, household entities who protected hearth and wealth.

At #123 is a real find, a doorway flanked by a pair of mermaid-like caryatids. But they aren’t in the best of shape. One of the lovely mermaids has had an arm broken off, while the other one has completely lost her head. The geezer over the window has weathered badly, as well. The rest of the building looks as if it was subject to a bland makeover awhile back, eliminating whatever other decoration it had.

Henry Street between Pike and Rutgers, looking southwest toward the Manhattan Bridge, Woolworth Building and #1 WTC.

#135 and #137 Henry, modest brick walkups. One is a shul, Congregation Sons of Moses, while the other is home to Immigrant Social Services Inc. Scenes from the movie A Price Above Rubies were filmed at the shul in 1998, while the remains of Shmulka Bernstein, who ran what was at the time the only Chinese kosher restaurant in NYC, are buried within the plot. Henry Bookbinding, noted for custom handcrafted restoration of prayerbooks, is located in the basement of #135.

info from The Synagogues of New York’s Lower East Side, Gerard Wolfe, 2013 Fordham University Press

New Life Now Chinese Missionary Baptist Church, #136-138 Henry. I noted the presence of a classic neon cross “Jesus Saves’ sign. I wonder if it lights up at night.

At Rutgers Street we come to yet another very old, but repurposed, church building. The present St. Teresa Roman Catholic Church was built in 1841 as the First Presbyterian Church of New York. It is made of handsome Manhattan schist. The plot where it stands was donated by Henry Rutgers himself. St. Teresa’s parish assumed control very early on, in 1863.

There has been a church at the present site since 1798 when Henry Rutgers deeded out lands for development as New York City continued to expand beyond its old boundary at Wall Street. The church that was established was a Presbyterian church, and after several years of growth, it built the current structure in the early 1840’s. At that time the neighborhood was well established, and moderately prosperous, with the East River docks just a few blocks south. With its new building, Rutgers Presbyterian Church was there to stay.

However in the 1840s the first waves of Irish immigrants began arriving because of the potato famine. They flooded the neighborhood, changing what was a middle class protestant enclave into an Irish Catholic slum. The residents of the Lower East Side began to move, and with it them, the congregation of Rutgers Presbyterian, eventually settling at 73rd and Broadway, where it exists today…

St. Teresa’s had always been a poor parish, worshiping in an old building for which there had never been sufficient funds for proper maintenance. As a result, in 1995 the interior vaulted ceiling of the church collapsed, and 60,000 pounds of plaster fell, breaking through the floor into the basement parish hall. The congregation worshiped for months in a local synagogue, but eventually found the money to repair the floor so that they could worship in the church albeit in the basement. The future looked bleak. There was no money to repair the main church, and many argued that St. Teresa’s should be closed. However, the pastor at the time, Father Dennis Sullivan, and his parishioners were determined that St. Teresa’s would not close. After the school had been condemned and closed in 1942, it had been torn down and eventually become a parking lot, used by the church and neighborhood residents. The late 1990s were a time of rising property values, as New York City began to revitalize and the Lower East Side began to gentrify. Thus through the sale of the parking lot and adjacent air rights, the parish began extensive renovation of the church, including a new roof, new interior appointments salvaged from what was left from the old, and as the crowning glory of the church the restoration of three murals painted in the 1880s, depicting St. Patrick teaching the pagan kings of Ireland, St. Teresa’s teaching her sisters and the crucifixion. The church was reopened in the early winter of 2002 and solemnly rededicated by His Eminence Edward Cardinal Egan in early 2003. St. Teresa

A playground and a school building on Henry between Rutgers and Jefferson Streets are named for Jacob Joseph. In actuality they are named for two Jacob Josephs; the school for the first Jacob Joseph (1840-1902) who served as chief rabbi of New York City’s Association of American Orthodox Hebrew Congregations, a federation of Eastern European Jewish synagogues; and the playground for Captain Jacob Joseph (1920-1942), a great-grandson of the rabbi, who was killed in action in World War II at Guadalcanal.

Behind that red door opposite the Jacob Joseph playground is the rather presumptuously-named World Buddhist Center. Though the Lower East Side was predominately Jewish in the 20th Century, Chinatown has been continuing to spread east, north and west from its epicenter at Canal and Lafayette.

1880s-era undulating brick apartment building at Henry and Jefferson. The bay windows allow apartment dwellers to look up and down Henry Street. Unfortunately the decorative cornice has been torn off on the Henry Street side.

A mythological scene is displayed above the Henry Street entrance. Cupid and Psyche, perhaps.

Street trees appear for the first time on Henry east of Jefferson. In the neighborhood, there’s also a Clinton Street, so lower Manhattan features President William Jefferson Clinton’s full name.

The north side of Henry features an assortment of brick apartment buildings that were handsome in their day.

Wise heads prevail at #191 Henry Street.

I can’t vouch for the interiors, but here are two more examples from the golden age of tenement building. And the more soot and grime on the outside, the more character it has.

At Montgomery Street/Samuel Dickstein Plaza, you’re in Waldland. From Dickstein Plaza you can see a building with a back porch.

A back porch in New York City? They built houses with back porches in 1827, when 263, 265 and 267 Henry Street first appeared. In 1893 Lillian Wald started the Visiting Nurse Service here with philanthropist Jacob Schiff, an institution that is still going strong today. Wald also started the Henry Street Settlement, an organization bringing a wide range of arts and social services to its community. The Settlement has grown in its over-100 year history to encompass 18 buildings — an it continues to expand. Oddly, both Lillian Wald and Jacob Schiff had NYC thoroughfares named for them, but both have fallen into disuse: Lillian Wald Drive had been East Houston Street between Avenue D and the FDR Drive, while the middle lane of Delancey Street between Bowery and The Williamsburg Bridge had been known as Schiff Parkway.

The Henry street Settlement hopes to convert the former Engine Company 15 firehouse at 269 Henry Street (built in 1883) into a community center. The fire station moved a few blocks away to 25 Pitt Street in 2001. It’s among one of the handsomest firehouses (or former firehouses) in town, with liberal use of terracotta, which appears to be imitating burning flames.

I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine

The original name of St. Augustine’s Episcopal Chapel at #290 Henry near Jackson Street was All Saints Free Church, which is still carved over the front entrance. It too was made from Manhattan schist, like St. Teresa’s as well as First Chinese Presbyterian Churches (see above). It was completed in 1829. In “free” churches, rent was not charged for pews. In 1949, the congregation merged with St. Augustine’s Chapel of Trinity Church, then located at 107 East Houston Street, and the new combined congregation used the building on Henry Street.The parish became independent of Trinity in 1976.

301 Henry Street, of the Henry Street Settlement, consist of “Helen’s House” and “Pete’s House.” Helen’s House opened in 1991:

The building known as Helen’s House is named in honor of Helen Hall, who followed Lillian Wald as Head Worker of Henry Street Settlement in 1933. She directed the Settlement for over 30 years and was an author and activist concentrating on social reform in policies focusing on homelessness and municipal shelters. Today, Helen’s House provides emergency housing for mothers or fathers with children up to the age of seven…

Pete’s House, the earlier of the two structures, originally held a pair of row houses that were altered over the years for multiple housing. By 1920, the two original buildings were functioning as a small synagogue. The Settlement acquired the property, and with extensive alterations converted it into a youth center. The project, funded by Edith and Herbert Lehman, was named Pete’s House in memory of their son Peter, who had worked as a volunteer youth leader at the Settlement. During World War II he was an officer in the U.S. Air Force, and was killed in England in 1944. Henry Street Settlement

Charles and Stella Guttman Building, Henry Street Settlement, completed in 1962. I usually don’t like 1960s architecture — I consider it cold and forbidding — but this building is an exception to that rule.

The four-story with basement structure has white glazed brick, blue and yellow terracotta spandrel panels and limestone columns and copings clad across the upper front facade. The original renderings of the building called for a glass curtain wall between the columns across the first level at the street level. Instead, the architects used blue tiles showing animal and jungle fantasies designed by the children from the Settlement’s art programs. The prominent limestone band above the first level is carved with the benefactor’s names. The interior lobby retains the original multi-color glass one-inch wall tile, which was very popular during the period. The addition upgraded the youth center with an elevator, HVAC system, gymnasium, classrooms, and library that more than doubled the Settlement’s capacity to serve the youth in the community. Henry Street Settlement

Henry Street ends at Grand Street, the Corlears Hook Houses and a gaggle of CitiBikes.

3/2/14