The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, opened in May 1950 and designed by Ole Singstad, remains the longest vehicular tunnel in the world after nearly 65 years in operation. Work got underway in 1940, but World War II diverted raw materials and manpower to the war effort and the tunnel did not continue construction until 1946. In the interim, NYC’s traffic czar Robert Moses attempted to scuttle the tunnel in favor of his dream project, a vast suspension bridge connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt (never a fan of Moses’ in any case) used an executive order to derail the bridge, citing security measures. It would be a large target for the enemy; such circumstances would be played out tragically several decades later with the twin towers of the World Trade Center. The tunnel was officially renamed for former NYS Governor Hugh Carey in 2012, but most New Yorkers are resistant to such renamings and stick to calling it the “Battery Tunnel.”

The early 1950s saw new lamppost designs appearing on New York City streets. The Art Deco, Machine Age and Art Moderne movements in architecture had given rise to new, streamlined forms with little to no extra ornamentation. Gone were the intricate wrought-iron scrollwork and filigree that had characterized such forms as the Bishop Crook and the longarmed Corvington lampposts that had dominated streets since the 1890s. New, octagonal-shafted posts painted silver gradually took over NYC streets beginning in 1950 and gradually replacing earlier forms.

Park Avenue north of Grand Central Terminal, though, gained its own exclusive design that, singularly, was used in Twin forms on the avenue sides and in single forms bordering the median. They were simply designed with brackets and a ziggurat-styled base. They also had “mini-me” fire alarm light brackets.

This is the same lamp at Park Avenue and East 56th taken a few years later in, I’d say, about 1962 or 1963. A couple of years after this, these unique Park Avenue lampposts were scuttled and replaced with another unique design of the time, the modular Donald Deskey posts that first debuted in 1958.

And that was that… none of those Park Avenue-design lamps remain in operation. Or are there still some survivors?

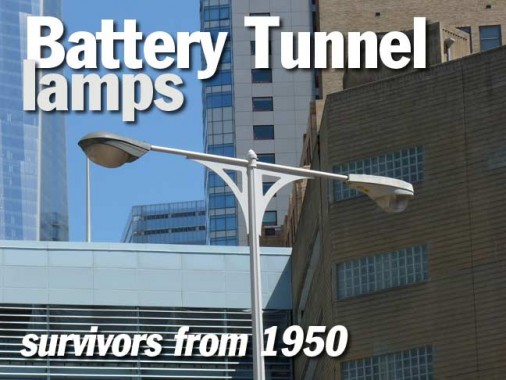

Returning to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, which still has a large number of its original streetlamps on the approach ramps in both Manhattan and Brooklyn, and they bear a very close resemblance to the Park Avenue lamps, other than being somewhat taller and with a bit less metalwork at their apices. Since they are on Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority property, NYC has no power to remove them.

The city has not felt a necessity to replace the lamps, since they have a streamlined, timeless quality.

There are also a number of these lamps, in Twin and single versions, at the Brooklyn side. I’m using here a Google Street View photo of the bellmouth area, but some years ago — I’m not sure if it was before or after 9/11/01 — I was prevented by a police officer from taking photos in the area, based on security concerns. I suppose such restrictions do not apply to Google!

Many of the posts preserve the General Electric M-1000 luminaires, rarely employed in New York City (I remember them being frequently found in Albany, New York). They look like the GE M-400‘s older and bigger brothers. The M-1000s are usually used in busy areas that need a larger coverage. With light-emitting diode lamps now assuming a greater and greater role, the Battery Tunnel M-1000’s days may be numbered.

The tunnel approach lamps aren’t the only survivors in the area. Local streets surrounding the tunnel also preserve a number of longarmed “Corvington” lamps that first appeared in the 1910s and were installed until the 1940s. After falling out of favor for a few decades, many NYC avenues gained retro versions of this design, but only a few originals can be found here. Two are found west of the tunnel, one on Washington Street and the other on Morris Street. But even these two differ from each other.

The example on Morris Street is the older of the two. It still has complete scrollwork between the mast and the shaft. Compare this post to…

… the post on Washington and Morris. The scrollwork is much reduced and it looks like a “decadent” version of the original. It was likely installed in the 1940s and cost-cutting associated with WWII forced the city to remove some of the ironwork.

Four more “Corvs” survive on the east side of the tunnel on Greenwich Street and Morris Street. They are in constant danger from truck traffic, but they have survived from at least the 1940s.

The pedestrian bridge that spans the tunnel and connects the two parts of Morris Street is also original to the tunnel opening in 1950 and still has its original davit lampposts. These originally carried incandescent “gumball” luminaires. Unfortunately the city has used its favorite bridge paint color, maroon, but the brand the city uses fades to pink in the sun just a few years after it’s applied. Rumor has it that the city will be replacing this bridge sometime soon.

1/1/16