No, it’s not what you think, this isn’t really “nude” Utrecht, and I didn’t stumble on a Spencer Tunick (link NSFW) tableau when out adventuring. I was actually on my way to Church Avenue (the results of which can be seen here) when I decided to indulge a fascination of mine for many years: the three blocks of New Utrecht Avenue that are uncovered by an elevated train. When riding the buses all over southern Brooklyn as a kid, I was on the B35 one day rolling up 39th Street and passed an elevated train over 10th Avenue instead of where it “should” have been, on New Utrecht Avenue. This called for some research.

New Utrecht Avenue runs southeast from about the intersection of 9th Avenue and 39th Street a few miles to 86th Street just past its intersection with 18th Avenue. For most of its length the West End elevated line shadows it. For many years, B and M trains plied the line, but several years ago when repairs to the Manhattan Bridge were completed and trains began running on both sides of it again, the alphabet soup of Brooklyn subway lines was re-stirred and the B was assigned to the Brighton line, buddying up with the Q, while the D wound up on the West End. By 2010, the M was running between two termini in Queens, Continental Avenue in Forest Hills and Metropolitan Avenue in Middle Village.

New Utrecht (pronounced, in Brooklyn, at least, “YOU-trekt”) Avenue was so named because it went to the Town of New Utrecht, founded in the 1600s and one of the six towns that existed in Kings County before all were consolidated into the City of Brooklyn in 1896 and then into New York City in 1898. The town of New Utrecht was named for Utrecht, Netherlands, the 4th largest city in that country. In Dutch, “Utrecht” is derived from two words that mean “old fort,” so that “New Utrecht” literally means “New Old Fort.”

I was surprised to learn during my research that New Utrecht Avenue existed long before the railroad that ran along it and the elevated train that replaced it ever existed. The road was laid out in the 1830s after some protracted negotiations with Dutch landowners, descendants of original settlers, and attained its full length in the 1850s. It was known in its early years as the Brooklyn, Greenwood and Bath Plank Road, as it originally had a wood roadbed and stretched from the southern edge of the City of Brooklyn at Green-Wood Cemetery and ran to Bath Beach, named for the British spa town on the Avon, famous in high-school British lit classes for the Wife of Bath, the randy, frequently-married heroine featured in Geoffrey Chaucer’s 14th-Century Canterbury Tales. This was a recreational area in Brooklyn too, as villas and yacht clubs clustered near the shore, until the Depression ended its run as a resort.

The railroad becomes part of the New Utrecht Avenue story in 1863, when a steam railroad built by Charles Godfrey Gunther, a former NYC mayor, was built from the entrance to Green-Wood Cemetery to Bath Beach. The line necessitated a transfer at 36th Street (just as today’s subways do from the D to the N and R) because steam railroads were forbidden in Brooklyn in that era. A horsecar line completed the run from 5th and 36th to 5th and 25th. The steam line was completed out to Coney Island in 1864, where it met the West End Hotel. After an 1885 reorganization the line became the Brooklyn, Bath and West End Railroad, was electrified by overhead catenary wire in 1893, was acquired by Brooklyn Rapid Transit in 1898, and finally, was replaced by the West End Elevated in November 1916. Unfortunately, Godfrey’s name never attached itself to subsequent iterations of his railroad the way Andrew Culver’s did to what is now the F train in Brooklyn.

Where’s the El?

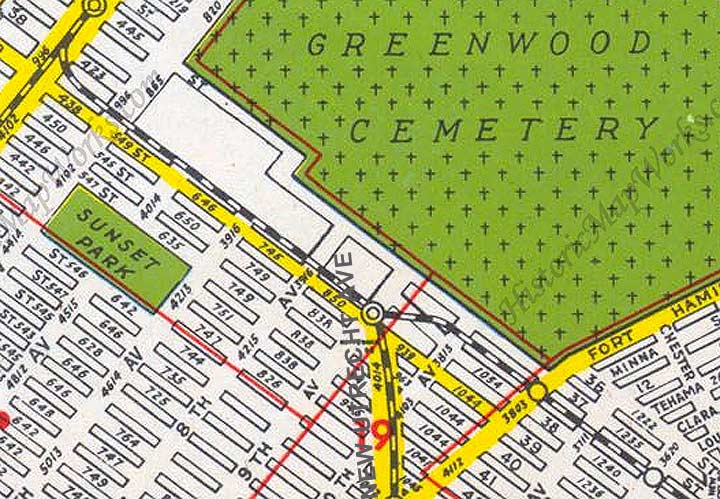

Getting back to my premise, when I was riding in that B35 bus all those years ago, I was mystified that the el was on 10th Avenue, not New Utrecht Avenue. My amazement is rooted on this Hagstrom map, here in a 1948 edition, but rendered like this until the hand-drawn map was discontinued in 1998 and succeeded by a computer-generated edition — it shows the West End El proceeding merrily up New Utrecht Avenue all the way to 9th Avenue, when in reality, it turns onto 10th Avenue at 41st Street, runs there for two blocks, and turns onto a right-of way north of 39th Street.

All of the hand-drawn street maps in common release for many years that indicated transit lines — Hagstrom, Geographia, and Colorprint (distributed by American Maps) perpetuated this error and continue to do so — Geographia, which still distributes hand-drawn editions, and Hagstrom, which started using computer-generated maps for NYC in 1998. It’s a small point, but these companies otherwise strive for accuracy.

One exception to this was the Belcher-Hyde maps, which showed tremendous detail not possible on other maps of smaller scale. In 1929 Belcher-Hyde produced what they called a “Brooklyn Desk Atlas.” For many years my experience with it was limited to a crumbling copy in the archives of the Brooklyn Business Library; several years later, Brian Merlis of brooklynpix showed me a pristine copy in his personal collection. However, Historic Map Works has had it online for a few years now. The desk atlas was likely high-priced for the time and did not compete with the mass-market maps produced by Rand McNally and other map makers in the 1920s.

On the atlas, elevated lines are shown by thin straight lines, interrupted to show street names, interspersed with dots. Note that here, the West End Line is correctly depicted as diverging from New Utrecht Avenue at 10th Avenue, following it for two blocks, then turning left.

Google Maps, correct about 95% of the time, gets the configuration right here, with the D train following its actual course.

So… why has this error been perpetrated all these years? I really do not have any idea. Hagstrom first produced NYC street maps in 1916, but I do not know if the earliest editions featured transit lines. That was the year that the surface line along the avenue ended and the el began service, so showing it running straight down New Utrecht Avenue may be a carryover from earlier maps showing that instead of the 10th Avenue detour. The answer may be that it was easier to draw the lines that way, but that hasn’t stopped otherwise accurate depictions on other transit lines.

9th Avenue

The first building located on New Utrecht Avenue is the 9th Avenue stationhouse serving D trains, the easternmost end of a large transit complex combining subway yards and a bus depot. Just east of the station, the West End swiftly rises to an elevated structure, where it remains all the way to Coney Island. Years ago when I first saw the station, it had a set of antiquated platform lamps:

When the station was renovated in 2012, these older numbers were removed and a new set of stanchions was installed that are quite sympathetic to, and resemble, the originals that were removed.

In addition, new station identifiers were installed on stanchions that look like massive versions of the lamp bases, a clever design idea.

Looking at the west end of the 9th Avenue platform. Because of shadows, it’s hard to see, but there is a set of tracks on the left that run into a now-shuttered lower level of the 9th Avenue station. It had a center platform, tiled walls that resembled other BMT stations (think of the express stations on the 4th Avenue line), large enamel navy blue and white plaques with the station name, “9th Avenue” hanging from the ceiling, and white and black enamel signs with the number 9 on supporting pillars. The lower level served Culver Line bound trains from 1919 to 1954, and Culver shuttle trains from 1954 to 1975, after which the lower level was no longer used for passenger service. NYC Subway has a few dozen photos of the lower level.

However, the lower level wasn’t quite finished after that, because in the final scene of the 1987 movie Crocodile Dundee it stands in for the IND 59th Street-Columbus Circle station in which Croc “walks” on the shoulders of a platform crowd to rejoin his girlfriend played by Linda Kozlowski.

I’ve often cited original IRT stationhouses at Bowling Green, 72nd Street and Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn as relics worthy of note, but I haven’t paid nearly enough attention to original BMT stationhouses erected in the 1910s when as part of the Dual Contracts that funded subway construction for both the IRT and Brooklyn Rapid Transit, dozens of such houses were built serving those parts of the line that were in open cuts. The Brighton Line (Q, B) has Prospect Park and Parkside Avenue, and the Sea Beach (N) has a whole series of them between 8th Avenue and 86th Street. There’s only one on the West End here on 9th Avenue and, after renovations in 2012, it’s a gem. For many years, the front entrance was blocked up despite the large “subway entrance” sign. The exteriors of these stations feature terra cotta with diamonds and circles that are frequently used as a BMT motif.

In a 2012 makeover, most of the original BMT (when built in 1916, BRT) decorative elements such as tiling and mosaics were retained, while new overhead lights, again using the original arts and crafts design, were installed. Most of subway design, in the IRT, BMT and beginning in the 1930s, IND, were under the supervision of architectural designer/engineer Squire Vickers. (I like to think that Jonny Ive has had a similar role in Apple Computers.)

In many BMT stations, the intricate mosaic work has several layers of dirt and can’t be readily made out. During the 9th Avenue makeover, the mosaics are revealed to be quite intricate and colorful, with circles and diamonds in buff, brown, aqua, light green and dark blue.

Skylights add some airiness to what could be an otherwise drab experience.

Back wall and bulletin board for frequent service changes, subway map and surveillance cameras.

When I first saw this installation on the outside fencing, I assumed it was a tribute to houseflies, but without color it’s hard to tell one bug from the other. It’s actually Christopher Russell’s “Bees for Sunset Park.” (We’re close to the undefended border of Borough Park and Sunset Park, which to me runs down 9th Avenue or Fort Hamilton Parkway.)

Russell:

The station is like a kiosk, and it reminded me of beehives — of people coming in and out of it, and doing their jobs. I began to think about the great gates that Gaudí did. He came from a family of ironworkers, and there’s a fantastic dragon gate he did in Barcelona.

Metalwork and gates were definitely an aspect of the Arts and Crafts tradition, and that was very much on my mind. I also thought about Mackintosh and his buildings in Glasgow. NY Times

9th Avenue reaches its eastern end at 37th Street and Green-Wood Cemetery. When I was a kid, I thought of 9th Avenue as a somewhat mysterious entity, since it did NOT extend into Bay Ridge. Because of a changing angle of street grid orientation, 10th Avenue follows 7th as you travel southeast on 86th Street, while 8th Avenue begins at 73rd and 9th Avenue at Bay Ridge Parkway, where its eastern path was interrupted as frequently as I perceived that the cartoons were by breaking news reports. 9th Avenue was stopped cold by Leif Ericson Square, and then by the open cut of the N train. Its only continuous stretch runs from the cemetery and 37th Street to 61st Street, where it meets the open cut.

Add to that the fact that in the 1970s, on my bicycling rounds I discovered that the very fence, where the arrow sign is located now, had a diamond shaped sign saying “DEAD END” on it. In front of a cemetery, no less! Never mind that it wasn’t really a dead end and motorists could proceed in either direction. Eventually the sign was removed.

I had despaired of finding a “DEAD END” sign in front of a cemetery ever again. But fear not. One exists here on the westbound Eliot Avenue in Maspeth as it runs between Mount Olivet and Lutheran (All-Faiths) Cemetery. When the road was built in the 1930s, apparently the city could only displace the bare minimum of territory in the cemeteries, so Eliot shrinks to two lanes. That means that one of the westbound lanes comes to… a dead end!

Just past the cemetery and the BMT stationhouse, the first order of business of the newly minted New Utrecht Avenue is to form a green triangle with 9th Avenue and 39th Street. While the Department of Transportation refers to this as “Heffernan Square” the Parks Department correctly calls it “Heffernan Triangle.”

I do not have any direct research on the Heffernan for whom the square is named. I gather that the Brooklyn Eagle reported that the triangle was named anywhere from 1932-1934 but the Eagle archives is now behind a paywall, so I’m not sure which year. My suspicion is James J. Heffernan (1888-1967) who was elected as a US Representative for the first of five terms in 1940. However, in 1933 he was serving as the Traffic Commissioner for the borough of Brooklyn.

If you know if it was another Heffernan, fire away in Comments.

“Nude” Utrecht

To be frank there’s not much to write home to Mother about on the two unshrouded blocks of New Utrecht Avenue. If hipsters invade the Sunset-Borough Parks border and want to open up a barber/haberdasher shop, or artisanal chocolates with recipes purloined from other companies, or organ meat restaurants with stuffed animal heads on the walls on New Utrecht Avenue, they can go ahead and call it “Nude Utrecht.” It’d be fine by me.

These three aluminum-sided dwellings appear to be quite old, and they do show up on the 1929 area map above as small yellow rectangles.

If you look at an overhead shot from Google Street View, this complex at NUA and 40th Street is shaped like a large check mark.

New Utrecht Avenue looking north toward the cemetery.

A Jewish grade school occupies the NW corner of NYU and 41st Street.

Here, though, the el swoops in off 10th Avenue and runs in the same path as the ancient steam railroad built by Charles G. Gunther in 1864. NUA will be in shadow all the way to 86th Street.

Backtracking up 10th Avenue (interestingly an el train runs on brief portions of a 10th Avenue in Brooklyn and also in upper Manhattan) I passed the site, at 40th Street, of one of my more evocative FNY photos…

When I passed the building in 2007, it appeared that the beauty parlor storefront had been there untouched for decades.

Finally, here’s the spot where I rode on a bus as a kid and was first mystified about what an el train was doing here…

1/31/16