By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

This piece originally appeared in FNY in April 2010, but was never transcribed when I switched to the WordPress platform the following year. Sergey updated the article in February 2015.

The Rockaway Peninsula of Queens never disappoints an urban explorer. Physically separated from the rest of New York City by water, it often feels like a forgotten sixth borough. Located at the city’s southeastern corner, Far Rockaway marks the end of the city’s longest subway line, boardwalk, and the start of the peninsula’s local street numbers.

Cornered by Seagirt Boulevard, Nassau Expressway, and East Rockaway Inlet, this corner of Far Rockaway forms a tight enclave, connected to the rest of Queens by just one road- Seagirt Avenue. The first numbered street, Beach 2 Street actually lies within the town of Lawrence in Nassau County.

In this 1898 map, Atlantic Beach was attached to the Rockaway peninsula by a thin sandbar. The future East Rockaway Inlet was known as Bay of Far Rockaway.

The phantom that is Hog Island existed as a sandbar just off the coast. It led a brief 30-year existence as a summer resort. Constantly reduced in size by storm waves, it was abandoned in late 1895, and in the following year, it went the way of Atlantis. Once in a while it deposits its gifts ashore, in the form of old whiskey bottles and smoking pipes.

Coastal beaches and barrier islands are almost as fluid as the water that surrounds them. Their forms are shaped by currents over the centuries. Along the southern shore of Long Island, the current flows westward, carrying its sands towards Atlantic Beach. If left alone, it is possible that the inlet could again be plugged by sand, reuniting Nassau and Queens.

The current also has extended the Rockaway Peninsula further west over the past century, completely shielding Jamaica Bay from the open waters of Atlantic Ocean.

In contrast to the city’s heavily-used beaches, at the confluence of the inlet and the ocean, towering dunes mark the beginning of a healthy barrier island. The hardy dune grass seeds deposited atop shell fragments hold the sand together, creating a primary dune. Behind the dune, species that are less tolerant of sand and salt spray begin to grow.

The primary dune also softens the impact of storm surges that threaten the human development in the background. At the same time, primary dunes cannot sustain too much weight. Stepping onto the dune can break the roots that hold the sand together. The dune would then collapse like a house of cards, undoing years of natural dune construction.

To protect the dune, the city should fence it off, but I hear that our parks budget keeps getting battered by stormy economic conditions.

Boaters beware: the confluence of East Rockaway Inlet and the Atlantic Ocean is full of sandbars that can strand a vessel.

The inlet is constantly dredged, and its wave-free beaches appear safe for swimming. But step into the water, and it’s very deep, and fast-moving. On the right above, appears to be a memorial for a drowned youth. In the background is Atlantic Beach Bridge, a toll bridge that marks the eastern terminus of state highway 878 also called Nassau Expressway.

Across the inlet, Silver Point Park still has a few bungalows and a private beach club. Having a jetty at the tip of Long Beach Island makes it an ideal spot for surfing. The park is open for local residents only.

The Ocean Promenade has its beginning in concrete, resembling a speedway. It extends west towards Beach 126th Street in the Belle Harbor neighborhood.

Many of the residents in these massive projects are elderly Russian Jews, but they often feel isolated there, in contrast to the tight-knit Brighton Beach, which gained fame as the Odessa of Brooklyn, named after the famed Ukrainian seaside city.

Most of the local population comprises of Orthodox Jews and African Americans, with a few Latinos and Irish.

The public plaza, known as O’Donohue Park, at Beach 9th Street, marks the starting point of the city’s longest waterfront promenade. A war memorial by the local Jewish War Veterans chapter looks towards the ocean. Prior to its acquisition by the City in 1942, O’Donohue Park was a private community of summer homes and common space at the foot of Jarvis Lane, which later became Beach 9th Street. The land was purchased by Mary O’Donohue in 1868 and her heirs continued to develop the property as a summer beach destination. In 1925, developer Isaac Zaret purchased the property, naming it O’Donohue Park with the intention of building fifty homes on the site. The plan failed to materialize and by 1938, it had fallen into foreclosure.

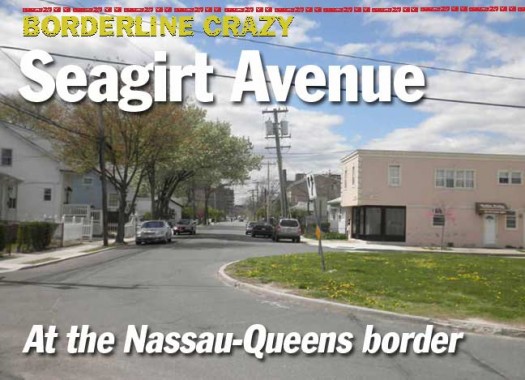

Seagirt Avenue

“Seagirt” is an old English term for “surrounded by the sea.” At Beach 9th Street, Seagirt Avenue merges into its outgrown child, the pedal-to-the-metal Seagirt Boulevard, which was built in 1952 as a successor to the old coastal avenue.

Believe it or not, this Q113 bus offers a one-seat ride to downtown Jamaica on the mainland of Queens. It’s only an hour away by bus. Car services and buses are a must around here. With its sizable elderly population, access-a-ride vans can also be frequently spotted.

Before 1952, Seagirt Avenue was the main path in and out of this enclave, which was separated from the rest of Far Rockaway by wetlands. Once the new Atlantic Beach bridge was complete, a sand strip across the wetlands became the high-speed Seagirt Boulevard. Since then, Seagirt Avenue and its waterfront homes have become a quiet backwater.

During my visit to Seagirt Avenue in April 2010, I passed by the abandoned Coronado Court bungalow colony, where tenants had a backyard stream for dipping their feet, or for a swim, the beach on the inlet is a short block away.

Before Cancun and Punta Cana became affordable for the average working New Yorker, the bungalows of Brighton Beach and the Rockaways served as the ideal summer home. With air travel becoming more affordable and white flight to the suburbs, the city proposed razing the shacks to make way for housing projects. Wholesale condemnations took place, but the projects never came, and the homes sat empty. Squatters and vandals took over these shacks. But all is not lost, and there are local preservationists fighting to preserve this slice of vacation history. At their height, some 100,000 bungalow units turned the peninsula into a seasonal city. Bungalows were once as plentiful on the Rockaways as brownstones were in Park Slope.

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy in October 2012, nothing remains of Coronado Court.

The Coronado bungalows overlook Bridge Creek, which separates this heel of Far Rockaway from the rest of the neighborhood. In 1995, the city obtained ownership of property lots along the stream, designating the land as “Seagirt Avenue Wetlands,” preserving the stream from further development. The red line on the far right of the map is the city line, and 9 homes along Beach 2nd Street have their backyards in New York City, but front porches and addresses in Nassau County. They must pay taxes to both jurisdictions.

The Roman numeral system does not have zero, and the Beach numbering system in the Rockaways does not have number one. Its first number is Beach 2, continuing to Beach 227th Street at Breezy Point, a private enclave at the western tip of Rockaway Peninsula.

Similar to other major metro area bridges, Atlantic Beach Bridge has its own defining sign, shaped like a peanut.

This street corner sits on the county line, and uses city-issued street signs. In contrast, most Nassau County street signs are also green, but much smaller, sitting atop their own poles, rather than lampposts. Like Lawrence, the Nassau hamlets of Elmont, Bellerose, Floral Park, and New Hyde Park, also allow a few city numbered streets to penetrate into their domains.

If there ever were plans for a Beach 1st Street, that land was eaten up in 1950 for the present Atlantic Beach Bridge.

The bascule drawbridge to Atlantic Beach flies above the well-kept tip of Beach 2nd Street.

A tiny private beach is tucked behind the hedges.

In this photo, I am standing entirely in Nassau County. The city line is just a few feet to my right.

By boat, once your eastward vessel crosses under the bridge, East Rockaway Inlet becomes Reynolds Channel. Just as many major streets change names once the cross the county line, so does this waterway.

The Lawrence Cove Association runs this private beach between Beach 2nd and Beach 3rd streets. The city line enters the water in the middle of the crescent-shaped cove.

Far Rockaway has always had a curious relationship with its wealthier Five Towns neighbors. To distance themselves from their neighborhood image of tough housing projects, some local residents address their homes as “West Lawrence,” while still enjoying the lower taxes of New York City. This is similar to how some residents of Riverdale write “Riverdale, NY” while most residents of that borough address their homes in “Bronx, NY.”

Of particular interest, the local Orthodox Jewish community is now experiencing rapid growth, with young families drawn to Far Rockaway’s relatively affordable suburban lifestyle. Being a coastal area on the city’s eastern fringe, 10 minutes from JFK Airport, it may well be New York City’s closest point to Israel. Looking out to sea, I squinted, but still could not see Tel Aviv.

At one point, Rockaway residents even contemplated seceding from the world’s greatest city, citing neglect.

Looking west into the city from the city line, Seagirt Avenue begins here. Many of the homes on this once-heavily trafficked road date back to a time when Lawrence Cove was a summer vacation mecca. This traffic circle at Seagirt Avenue and Beach 2nd Street straddles the city line.

Beach 2nd Street crosses over Bridge Creek to connect with Seagirt Boulevard and Nassau Expressway. Looking east, Bridge Creek dips beneath the toll plaza of Atlantic Beach Bridge. Operated by Nassau County, it is the last cash-only toll crossing in the state and a source of annoyance to drivers. As locals describe it, the cash-only toll was kept in place by Atlantic Beach residents eager to keep city folks out of their village.

Looking west onto Bridge Creek, the Roy Reuther Houses dominate the skyline. The tallest structure on the Rockaway Peninsula, it was built in 1971 under the auspices of the United Auto Workers. It is mostly occupied by retirees. This view from the Beach 2nd Street Bridge straddles the city line. The bridge is in Nassau, but this marina is within the city.

Signs pointing towards this peninsula often say the destination in plural. Everyone new to the city asks why there’s a The in The Bronx, but why is the peninsula addressed in the plural as The Rockaways? I suppose that it is a way to describe all the peninsular neighborhoods together in one grouping.

State Route 878 is a stub of an ambitious proposal to extend interstate highway 78 from the Holland Tunnel in Tribeca, above lower Manhattan, across Williamsburg Bridge, elevated above Brooklyn, and through southern Queens towards Atlantic Beach as Nassau Expressway.

Short of crossing the ocean itself, highway builder Robert Moses also sought to bring more traffic to the barrier islands with a ribbon of coastal parkways going from the Rockaways eastward through Fire Island.

Thankfully, his plans never saw the light of day. Instead, a healthy bike trail now supplements the lightly-used highway.

Sergey Kadinsky’s new book, Hidden Waters of New York City, is now available for pre-order.

2/3/16