During the waning light of November 2015, we had a spectacular midweek day — it could have been the day after Thanksgiving — and word had come about a brand spanking new pedestrian and bicycle connection between Port Morris, Bronx over the narrow but significant Bronx Kill into Randalls Island, a considerable expanse in the East River lying, along with Wards Island, to which it was annexed by landfill, between the three boroughs of Manhattan, Bronx and Queens. Naturally I got on my horse, so to speak, and made my way over. It was a fine day for it as the Randalls Island Connector, as it is called, was completely empty with just a few other souls making their way across…

GOOGLE MAP: PORT MORRIS TO THE UPPER EAST SIDE

At the end of Part One I had just finished making my way across the new Randalls Island Connector, the newest crossing between Manhattan and the Bronx, and was taking a look around.

Randalls and Wards Islands used to be separate islands in the East River between Manhattan and Long Islands until they were joined by landfill in the 1930s around the same time the Triborough Bridge was under construction. Randalls (for the purposes of expedience I’m eliminating the apostrophe, but it can appear with and without it) has had many names over the years, from the Native American name Minnahanonck to Montressor’s Island, after the British Army engineer who purchased it in 1772 and farmed the island with his wife until the Revolutionary War, when the British used it to make amphibious assaults on the surrounding territories. The island was sold to John Randel in 1784 and sold again to New York City by his heirs in 1835.

Like most of New York City’s isolated islands it was used to stash “undesirables” such as “inebriates,” orphans, and paupers. Long-demolished buildings housed them as well as recuperating Civil War veterans and what came to be known as juvenile delinquents. It wasn’t until the 20th Century that the islands began to be thought of as places for recreation. Downing Stadium was constructed in 1936 and served as a venue for sports events and concerts until 2002; briefly, it was home to the New York Cosmos soccer team in 1975, when the team signed Pelé. In 2005 Downing Stadium was replaced by the smaller Icahn Stadium which I’ll talk about presently.

There’s a network of roads on Randalls and Wards Islands, and until I took a ForgottenTour onto the island in 2011 for the 75th Anniversary of the Triborough Bridge I was unaware that they had names (consult the Google Maps route of this map linked above). I’m still unaware of when these roads got their names or when they got them, but I imagine the NYC Parks department had something to do with it.

At the end of Part 1, I showed a large area of ballfields which carry the formal name Sunken Meadow; the loop road surrounding them also carries the name. In Hidden Waters of New York City, FNY correspondent Sergey Kadinsky avers that Sunken Meadow Island was part of a trio of East River Islands that were combined into one by landfill, but I haven’t seen any other references to it — it seems to be completely forgotten, except by Parks.

One of the new-ish guard booths along Central Road. On my rare visits, it has not been occupied.

A look at the Triborough leg that spans the Bronx Kill. The main truss is 383 feet (117m) in length, while the approach is much longer, at 1217 feet (371m). The light tower overlooks two ballfields between the Triborough and the Bronx Kill Hell Gate Bridge span. Note the ramp proceeding down from the bridge stanchion on the right…

It’s the pedestrian-bike ramp connecting the bridge with Randalls Island. It’s perpetually in the shade and has not aged well, and if you’re a little east of here, the new Randalls Island Connector is rather more inviting.

At this point Central Road becomes Bronx Shore Road. I didn’t intend to press too far west, but there’s an interesting artifact here you should take a look at…

Just off Bronx Shore Road is the official headquarters of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. It’s pretty well guarded so I’m using a shot I got in 2011, when the authorities knew a tour would be coming through. The Moderne building opened in 1936, and for many years it was the location of the office of NYC traffic czar Robert Moses. Ironically, Moses did not drive and had to be chauffered to the building from Manhattan every day.

I found this NY Times reference from 1982 which lists this building as one of the locations where bridge tokens could be purchased in the pre-EZ Pass days.

The toll for the Triborough, Bronx-Whitestone, Throgs Neck and Verrazano-Narrows Bridges and Queens-Midtown and Brooklyn-Battery Tunnels is now $1.25 if paid in cash. A packet of 20 tokens costs $22, reducing the cost of each trip to $1.10.

Let that sink in for a second!

Another look at the Bronx Kill and a set of boxcars on the Oak Point spur in the Bronx.

Known as NY Reference Route 900G, the Harlem River lift span cionnecting Manhattan and Randalls Island was the longest highway lift bridge on the planet when opened in 1936. It is 770 feet (235m) in length, the main truss span is 310 feet (94m) in length, and the towers are 210 feet (64m) in heights. It can be raised to 135 feet (41m) above the river.

The Triborough was the last major bridge that Robert Moses deigned to include pedestrian and bike paths on (fearing riffraff and crime, the Traffic Czar did not put them on the Whitestone, Throg(g)s Neck and Verrazano-Narrows Bridges). These little viewing porticoes were included on both bridge stanchions on the Bronx Kill leg.

Back on Central Road, here’s the marvelously restored Discus Thrower statue, which stood on the Downing Stadium entrance plaza between 1936 and 1970. It was sculpted in 1924 by Kostas Dimitriadis for the Olympic Games held in Paris that year, and was returned to Randalls Island and fitted with a new base and pedestal in 1999 and rededicated in a ceremony that included Olympic discus thrower Al Oerter and marathoner Grete Weitz.

You always want to look at the fine print. Here’s the mark of the foundry in Paris where the statue was forged, directed by Alexis Rudier and his son, Eugene. The best known work produced at the Rudier forge was Auguste Rodin’s “The Thinker.”

There’s also an Astoria, Queens connection here, as the statue’s restoration was handled in 1999 by The Modern Art Foundry on 41st Street opposite the Steinway Mansion. The foundry was begun by John Spring in 1932.

I can never shoot enough photographs of the huge concrete stanchions that support the Hell Gate Bridge railroad tracks on Randalls Island. Scenes from a number of films including 1971’s The French Connection were filmed with the tracks in view.

Reverse arch spans on the Hell Gate Bridge.

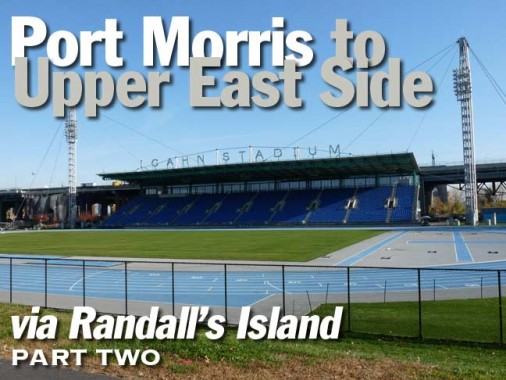

Yes, Icahn

Icahn Stadium, opened April 23, 2005, offers an extremely fast 400-meter Mondo Super X Performance running track, flanked by covered spectator seating for 5,000 and features modern locker rooms, showers as well as fitness, exercise and meeting rooms. A premier FIFA certified soccer field to the north of the Stadium has been built with an artificial surface, fencing, lighting and bleachers. Icahn Stadium is named after American businessman Carl Icahn. The New York Relays and other track and field events take a premier place in the schedule. The station isn’t large enough, however, to accommodate the large rock and orchestral concerts that Downing Stadium did.

Wards Island

Like Randalls Island, to which it is attached by landfill, Wards Island has been known by many names: the Native American Tenkenas, or “wild lands”; “Buchanan’s Island” and “Great Barn Island,” corruptions of the name of an early settler named Barendt; and Wards, for brothers Jasper and Bartolomew Ward, its owners following the Revolutionary War. The brothers founded a cotton mill and built a wooden span crossing the Harlem River in 1807 that lasted about 14 years before it was blown down in a storm. After 1840, it was used, like Randalls and Blackwell’s (now Roosevelt) Island as a relocation point for potters’ field remains, as well as a spate of asylums for ‘inebriates’ and ‘insane.’ The The New York City Asylum for the Insane opened on Wards Island in 1863, and its descendant, Manhattan Psychiatric Center, remains on Wards Island in a classic hospital building constructed in 1954. Interestingly it carries the address 600 East 125th Street, though it is really opposite 110th.

Wards and Randalls Island were once separated by a channel known as the Little Hell Gate (the real Hell Gate is about a mile to the south, at the southern end of Wards Island). A salt marsh, matching the one on the northern end of Randalls Island, is now maintained where the channel used to be. A boardwalk bisects the marsh, which provides Harlem River views.

The boardwalk leads over Little Hell Gate Bridge, which spans a short inlet: the only remnant of Little Hell Gate.

The view from here looks across to the Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics on Pleasant Avenue in East Harlem. Located in the building formerly occupied by Benjamin Franklin High School. It is one of Manhattan’s most academically accomplished high schools, graduating 97% of its senior class as recently as 2009.

The beetling Manhattan Psychiatric Center looms over the salt marsh. From here, you can go left, toward Central Road, more ballfields, and the pedestrian/bike bridge to Astoria across the Triborough, or turn right which leads to a pathway along the Harlem River and the 103rd Street Bridge to the Upper East Side.

Buildings of 1199 Housing Corp., a.k.a. East River Landing, a fairly new Corbusian affordable housing project on 1st Avenue between East 106th and 110th Streets.

Progressing apace along the Harlem River Pathway between the river and the well-fenced-off Psychiatric Center.

The Bronx Museum of the Arts has installed not-very-readable circular signs along the pathway.

The remains of a concrete jetty along the Harlem River shoreline.

At the southern end of Wards Island, Bob McCullough Field and the pedestrian path along East River Lane have unparalleled views of the classic Triborough Bridge link between the island and Astoria, Queens.

When I first walked in Wards Island in 2007, the pedestrian paths were not as, shall I say, manicured, and a dusty path that must have gotten quite muddy in wet weather led past the 953-bed capacity Charles H. Gay Center which has been billed as the largest homeless shelter in New York City.

There was plenty of open space to watch the orange sky and few fall buildings to block the view. A large football field with artificial turf lay across the street but the residents weren’t on it. It was used by a coed flag-football league that came on and off of Ward’s Island on rented school buses.

Inside the shelter, [Stephan] Ruffil shared a room with 15 strangers. Lights go on at 6 a.m. and most of the residents are out by 8 a.m. Some of the shelters (though not Charles H. Gay) lock bedroom doors from 1 p.m. to 6 p.m. to encourage residents to get out and look for work. Curfew is at 10 p.m. and if residents aren’t back, they end up spending most of the night outside.

After Ruffil headed in, a large man on a wheelchair came out. He was heading to 125th Street and Lexington Avenue to buy cigarettes. Daniel Ampo, 51, showed up early for the M35 because there’s only room for two wheelchairs. If there are more than two, and there often are, he’ll be forced to wait for the next bus. [“The Men Who Ride the Homeless Bus,”City Limits]

The late afternoon light was perfect to illuminate the blue of the Harlem River and the crimson of the changing trees.

A look south towards Midtown and the Queensboro Bridge. In the right foreground is Mill Rock Island, the site of the largest planned explosion in NYC history.

In 1701, John Marsh built a mill there that gave the island its name. The island was later squatted on by Sandy Gibson, who operated a farm on the island. At that time there were in fact two islands, Great and Little Mill Islands.

In 1885 the US Army detonated 300,000 lbs. of explosives on adjoining Flood Rock; that island had been the most treacherous impediment to East River shipping. It was most likely the most forceful explosion in NYC history and was felt as far away as Princeton, NJ. The decimated Flood Island was used to fill the space between Great and Little Mill Islands, producing Mill Rock.

Between the 1960s and 1980s there were various plans to make Mill Rock a park, but it didn’t work out. Too many rats.

Is it me you’re looking for? Before crossing the 103rd Street, or Wards Island, Bridge, here’s a look at what you see after you’ve crossed it onto Wards Island. It is a 2015 sculpture by Sharon Ma and according to the accompanying Parks department sign , it’s made of “florafelt, wood and succulents.” Florafelt is planting soil arranged vertically, while succulents are plants that have moist, fleshy parts.

The Ward’s Island pedestrian bridge was opened May 18, 1951, spanning the Harlem River to Ward’s Island at about East 103rd Street. It was designed to accommodate visitors to Wards and Randalls Islands’ park, stadium, psychiatric hospitals, and athletic facilities. It is a lift bridge: the center span, between the towers, can slide up to allow taller ship traffic to pass, though this happens rarely. Until 2015, when High Bridge reopened, this was the only pedestrian bridge crossing a major river in New York City. Also, until a couple of years ago the span would close for business in the cold months, but as Wards and Randalls underwent dramatic improvements, the decision was made by the city to keep it open year round.

The city retains the ability to close the bridge when necessary.

New LED lampposts have been installed replacing the previous davit-style posts.

The span’s two towers resemble large tuning forks.

A look from the walkway over the Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive, encompassing the Wards Island, Triborough and if you look closely, Hell Gate Bridges.

About as good a view of the Psychiatric Center you’ll get except from the inside. Maybe I’ll have my chance someday.

An overly complicated ramp system — the better to accommodate wheelchairs — leads directly to a playground beside the FDR Drive.

The East Harlem School, 309 East 103rd, is a striking building opened in 2008 and designed by Gluck & Partners.

“Full Circle” at 175 East 102nd Street, between Lexington and 3rd Avenues.

There is a subway stop at East 103rd and Lexington Avenues, which is at the crest of one of Manhattan’s steepest hills. It’s surprising to find hills like this south of Washington Heights; after the grid system began implementation in the early 1800s, most of Manhattan’s steeper hills were excavated and evened out.

This stretch of Lexington contains a number of curved-mast octagonal-shafted lampposts, among the first generation installed in the 1950s. These workhorses have carried a number of different luminaires, the latest being these VRDNs from Eaton Industries. They are among a number of light emitting diode lamp brands now being installed in NYC.

The NYC Transit bus depot on Lexington Avenue between East 99th and 100th is named for the Tuskegee Airmen, the nickname of the formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the United States Army Air Forces. They were the first African-American military aviators in the United States Armed Forces, formed in Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1941.

Reaching the 96th Street station, I figured it was time to kick it in the head– till the next journey to adventure.

4/10/16