I feel like doing another quick Sunday page this week instead of beginning a multi-parter, so I’ll draw on some images I got while visiting friends on Stockholm Street in Queens, just a couple of blocks from the Brooklyn border in June 2017. For decades the bastion of working class families with some industry and warehousing on the blocks north and south of Flushing Avenue (those businesses along Flushing Avenue replaced a row of colonial-era houses) I was also in an area that has attempted to rapidly gentrify, or hipsterfy, over the years. Almost sixty now (I have been hard at Forgotten NY since about age 40), I have to guard against calling anyplace that has restaurants, bars and entertainment catering to a younger crowd gentrifying. The latter term, as far as I know, refers to a situation in which outside developers attempt to change the cast or nature of a neighborhood by bringing in high-priced real estate, driving out people of modest means. No doubt, some of what is happening in what I’ve been calling “North Ridgewood” is part of this, while part of it is a natural progression. In any case, I’m an infrastructure commenter; on demographics, I’m on shakier ground.

There are plenty of streets that have more than one subway stop in NYC, but for me one of the most notable has been DeKalb Avenue; one of the two, which opened in 1916, is a major interchange between two separate BMT lines, one going down 4th Avenue in Brooklyn (R) and the other going down Flatbush Avenue (Q). The N and D, which also travel on those streets, bypass DeKalb, but that was not always the case in the past. Both trunks can switch to either the Manhattan Bridge or go through a tunnel to Manhattan.

The other DeKalb Avenue station opened here on the Canarsie BMT in 1928 on Wyckoff Avenue in Ridgewood (my criteria for Bushwick versus Ridgewood is simple; Bushwick is Brooklyn, Ridgewood is Queens, though it has been more complicated than that in the past). The landscape surrounding the two DeKalbs couldn’t be starker; the “downtown” DeKalb leaves you at Long Island University, the former Paramount Theater, along with the iconic Junior’s Restaurant a block from the Fulton Mall, the area now chockablock with anonymous glass towers. The Bushwick DeKalb leaves you along a major shopping spine loaded with apartment buildings, like the ones at the Stockholm Street exit shown above, constructed between 1900 and 1920. The demographics here are mainly Hispanic; classic “German” Ridgewood now commences further south. Streets in these parts bear Revolutionary War heroes’ names; Baron Johan DeKalb (1721-1780; he gave himself the title) was an Alsatian German soldier who arrived in the USA in 1777, fought with George Washington and was with him at Valley Forge, and perished after being taken prisoner by the British after the Battle of Camden in 1780.

Wyckoff Heights Medical Center at Wyckoff Avenue and Stockholm Street. I’m not sure there is a “Wyckoff Heights” — perhaps it’s a term made up by the hospital, since we’re between the two worlds of Bushwick and Ridgewood? The hospital was instituted by the Plattdeutsche Volkvest Verein, an organization of German immigrants, in 1889. Indeed it was known originally as the German Hospital when it opened, but anti-German sentiments forced a name change during World War II. I am unsure when this modern building opened.

Other name changes forced in northeast Brooklyn by WWI included Stanwix Street (Bremen) and Wilson Avenue (Hamburg).

I find Wyckoff Avenue interesting — I have chronicled it twice: once in 2010, the other time in 2016.

Stockholm Street, and the surrounding neighborhood in Ridgewood, is dominated by the twin-towered St. Aloysius Roman Catholic Church at Onderdonk Avenue. It was built between 1907 and 1917 (Francis Berlenbach, arch.). The parish celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2017; however, it has been seeking funds to restore its bell towers. The church is the largest building in the city constructed with Kreischer brick (see below). At 165 feet in height its twin campaniles are rivaled in the general area only by the Spanish Baroque St. Barbara’s R.C. Church at Central Avenue and Bleecker Street, eight avenues to the south. The twin towers can be seen as far away as Calvary Cemetery, a fair distance to the north across Newtown Creek.

Stockholm Street is a rare Landmarked District in Queens, a distinction granted in 2000.

I had always been under the impression that Stockholm Street in Bushwick and Ridgewood was so named in honor of a putative Scandinavian community that may have resided there. There was certainly a large one in Bay Ridge and Sunset Park.

I was wrong though; Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss’ handy Brooklyn By Name states that Stockholm Street was named for the Stockholm brothers, Andrew and Abraham, who provided land on which the Second Dutch Reformed Church, built in 1850 and still standing at Bushwick Avenue and Himrod Street (see this page) was built.

Pauline LeBlond, meanwhile, was a Ridgewood resident (1918-2006) who lobbied for years, ultimately successfully, to get the distinctive homes on Stockholm Street recognized by the LPC. The Department of Transportation had no capital B’s available when they made up the honorary street sign.

I always found Dutch names in NYC fun to say… Onderdonk, Knickerbocker, Amsterdam. Onderdonk Avenue was named for the Dutch Colonial Onderdonk family; their farmhouse, the original part of which dates to about 1710, is the last colonial-era house on Flushing Avenue still standing, home to the Ridgewood Historical Society.

Follow the yellow brick road to one of my favorite blocks not just in Queens, but in all of NYC. The street’s main claim to fame is a charming landmarked block boasting 36 homes built with yellow brick from the Balthazar Kreischer kilns of Staten Island.

There are similar rows of yellow brick houses elsewhere in Ridgewood and in Long Island City, but only these have the added attraction of thin, Doric-columned porches. The yellow-brick homes — which sit on the northeastern end of the street, between Onderdonk and Woodward Avenues — were nearly all constructed between 1907 and 1910, when German-Americans and immigrants from Germany were developing Ridgewood. The homes were developed by the architectural firm of Louis Berger & Company and built by Joseph Weiss & Co. Previously I had thought that the original yellow brick paving used Kreischer bricks, but according to Landmarks, the original bricks on Stockholm Street were produced by the S.B.T. Company, a major manufacturer of clay products, located in Clearfield, Pennsylvania. The yellow bricks were replaced by smoother versions with the same color in the late 1990s. Meanwhile, Type G telephone pole lamppost masts were installed by the city a few years later.

The King of All Buildings looms over Cypress and Seneca Avenues in Ridgewood looking west. Here is the view from Hart Street and Cypress.

Since I never spend much time on St. Nicholas Avenue (another street in Ridgewood-Bushwick with a Dutch theme, along with Onderdonk and Irving; author Washington Irving wrote extensively in fact and fiction about Dutch Colonial New York) I walked north on it here, and found the corner of Troutman Street, where Scott Avenue branches out and goes north at an angle.

This allows me to get into a bit of street map geekery and raise some questions that I don’t have answers for.

To me, it’s odd that Scott Avenue plunges south of Flushing Avenue. Flushing Avenue, which was straightened from a curving route called the Brooklyn-Newtown Turnpike in the late 1800s, is the dividing line between two street grids, north of it Williamsburg and East Williamsburg, and south, Bushwick-Ridgewood. But Scott Avenue reaches into (North) Ridgewood to the junction of Troutman Street and St. Nicholas Avenue.

Meanwhile, a few blocks west…

Knickerbocker Avenue also defies the grid, this time plunging north from the Ridgewood street grid into East Williamsburg, ending up at Johnson and Morgan Avenues.

I did a little research and both streets conformed to their respective grids until about 1900. However, 1912 maps show them in their present configurations, so both extensions took place between 1900 and 1912. The reasons why both streets were extended is unknown to me, but perhaps, someone has the information, and if so, feel free to post in Comments.

St. Nicholas Avenue and Troutman Street are great repositories of modern street art in (North) Ridgewood, but first, here’s some ancient painted art, an ID for Putnam & Company Ladders, which left the premises long ago– though Putnam Rolling Ladders, around since 1905, is still very much in business. I also knew I’d seen something about Putnam Ladders before–and I had, on Crosby Street at Howard in SoHo.

The SW corner of St. Nicholas Avenue and Troutman features a colorful wall art tribute to Brooklyn, alongside the new Idlewild bar, formerly called The Bodega; it’s likely a neighborhood bodega, or grocery store, was originally in this spot.

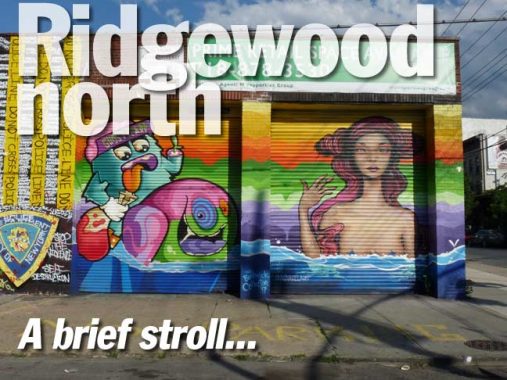

The artwork on St. Nicholas Avenue and Troutman Street was produced by a variety of artists under the Bushwick Collective umbrella; officially, we’re a block west of the Brooklyn-Queens line, so officially in Bushwick.

The accidental curator of the collective is Joseph Ficalora, a Native of Bushwick and Brooklyn. In 1991, Joseph’s father, Ignazio Ficalora, was killed on the way home from the family steel fabrication business. He was murdered for a few dollars in his wallet and the gold chain he had around his neck. At the time Joseph was only twelve years old. A few years ago, in 2011, Joseph experienced another tragedy, the loss of his mother, who battled a brain tumor for four years.

Joseph is now learning to heal from his years of growing up in a dirty and crime-ridden neighborhood by transforming the neighborhood and the walls of Bushwick into a safe & hip outdoor gallery. He has learned to wrangle the permits needed to legally display hundred of artist’s work. There is so much artwork to see you won’t be able to stop talking about it for days to come. [Free Tours By Foot]

On the Putnam Ladders wall. The image on the left came first. Also note the “Howard Street” address on the roofline.

Anyone know what’s going on here, with the skulls, moose or elk antlers, and “BHM”?

The Rookery, named for a communal gathering and breeding place for crows or rooks, is a wine and beer bar with exterior seating carved out of what was once a busy manufacturing and warehousing area; it’s become “on-trend” to create restaurants and bars in what the owners consider to be “industrial wastelands.”

More Troutman Street art from Bushwick Collective

Another ploy used by local restaurateurs is to make the exterior look as gritty as possible, with perhaps one small sign pointing out the entrance; in this case, Lot 45’s menus advertise its prices, which don’t seem to be listed online. Reviews are up and down.

Sea Wolf, identified only by small signs on the Wyckoff Avenue side with a picture of a wolf fish on them, is replete with Bushwick Collective art and has two sides open for al fresco dining. Its menu is readily available online.

Fittingly a mermaid is depicted on the Troutman St. wall opposite the seafood restaurant.

At Wyckoff and Troutman an ingenious solution is reached when the artist ran out of space: continue it on the sidewalk.

The Cobra Club on Wyckoff is an indistinguishable storefront, except for its weathered wood shingle sign.

From its self-description it’s hipster as hipster gets:

The Cobra Club is a bar. A coffee shop. A venue. A yoga studio. These titles may seem contradictory, at odds even, but we believe they are interconnected when you accept a diverse and dynamic life. These are all the things we love in life, and we have brought them together in one space to coexist and compliment one another.

Welcome to The Cobra Club. Yoga for your dark side, spirits for your soul. [Cobra Club]

I have something to admit to you. Those who know me for awhile will not dispute this. I have been 59 years old since I was 12. The Cobra Club seems far outside my usual realms.

The Jefferson Street subway station has been here on Wyckoff Avenue since 1928. Along the Canarsie Line (enjoy Manhattan service this year and next before the 15-month shutdown) there are a number of fairly obscure entrances (it took me quite awhile to find the one at Aberdeen Street). You’ll notice the difference for modern subway stops, like the ones just opened on 2nd Avenue.

That kicks it in the head for the Sunday page…

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

8/6/17