I took a number of walks in mid-December before a 2+ week deep freeze set in after Christmas, and a few of these occurred on some days that were quite overcast. In the warm months I prefer to walk in brighter weather, but in the cold months I don’t mind so much, as the sun angle from November until mid-February can create some very harsh shadows, with a sharp contrast between light and dark. I have neither the equipment or inclination to carefully set up each shot with umbrellas or other light-baffling stuff, so I just lighten them up in Photoshop a smidge. On this day, no need for any of that as we had a resolute cloud cover from start to finish.

Though I was familiar with Foster Avenue quite a bit from bicycling around Brooklyn as a youth before my move to Queens in 1993, I had never walked most of its length until this particular foray. I found some interesting items, and hopefully you’ll agree. I would up traversing it from McDonald Avenue east to Kings Highway. Foster Avenue continues northeast into Canarsie, but that stretch (much of which is rather boring) will have to wait for further adventures.

GOOGLE MAP: PARKVILLE TO BROWNSVILLE

When I ended Part 1 I was walking east on Foster Avenue and had gotten as far as Flatbush Avenue, about halfway on my trip. I have yet to walk the entire length of Flatbush Avenue looking for interesting infrastructure, but it’s on my list of things to do — taken as a whole, Flatbush Avenue runs from the Manhattan Bridge southeast, south and southeast again to the Marine Parkway (Gil Hodges) Bridge, where it plunges across to the Rockaway Peninsula past Floyd Bennett Field to Fort Tilden. Clearly this would be a walk for maximum daylight and would have to be undertaken during the warm months when daylight is at a maximum.

Flatbush Avenue attained its present form, at least on the map, in the post-Civil War era and is a straightened version of both Kings Highway, which originally ran from the Brooklyn waterfront southeast and then southwest to the Town of New Utrecht, and Old Flatbush Road. It encompasses worlds, both infrastructurally and demographically. It is named for the Dutch Town of Flatbush through which it ran. The word was originally the Dutch vlacke bos, “wooded plain.” “Bos” also appears in Bushwick, which means “town in the woods.” Over 20 years ago, journalist Allen Abel walked Flatbush Avenue’s length and wrote about it in Flatbush Odyssey, a book that was highly inspirational in my decision to begin this website.

In the photo above, the real estate at Flatbush and Bedford Avenues–the two lengthiest streets in Brooklyn–necessitates a mini-Flatiron of triangular proportions. Foster Avenue cuts across that X-shaped intersection.

Passing Flatbush Avenue, Foster Avenue assumes Avenue E’s old pathway and we plunge into East Flatbush. It’s ironic that in the Town of Flatbush’s lettered avenue scheme, E is skipped. It’s a casualty of the late 18th Century and early 20th Century developers to slap British-sounding monikers on what were previously anodyne lettered avenues. Hence, Avenue A became Albemarle; followed by Beverly, Clarendon, and Dorchester. The scheme was continued on Farragut Road, which presumably honors Admiral David Farragut, and the descriptive-sounding Glenwood Road. Weirdly, Avenue D was permitted to keep its name east of Flatbush Avenue, slotting in between the former Avenue C, Clarendon Road, and the old Avenue E, Foster Avenue; Dorchester Road is found only west of Flatbush Avenue.

Early in the 20th Century, Avenue E was renamed for the road that continued its path west of Flatbush Avenue, Foster Avenue. The origin of the Foster name is something of a mystery. In Brooklyn by Name, Benardo and Weiss aver that it was named for an 18th Century settler, James Foster, but I have found nothing else about him on the World Wide Web. Perhaps a deep dive into the Brooklyn Historical Society would uncover something.

2023: Fortunately, Joe Enright, a meticulous researcher, uncovers the truth in The View from Argyle Heights.

East Flatbush is a convenient name for a rather wide region carved out of the former Towns of Flatbush and Flatlands, found roughly between Flatbush Avenue and Ralph Avenues and from Foster south to the diagonal Flatlands Avenue, whence it becomes the neighborhood of Flatlands, named for the former town.

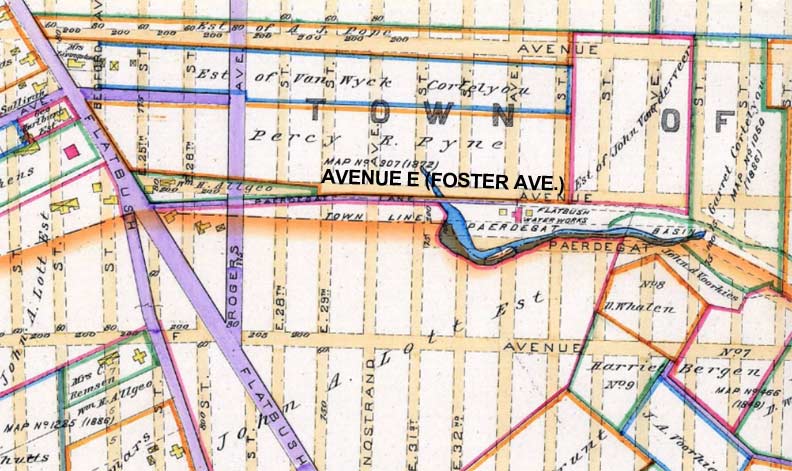

The map above shows the lay of the land around 1890. Purple roadways are paved, and beige paths with dotted lines are still just lines on paper. As you can see the Lott family still owned quite a bit of territory in what was still mostly pastures and estates.

These peaked and porched buildings on Foster and East 25th Street mark the couthern edge of Vanderveer Park, one of a number of enclaves, now most forgotten, such as Vanderveer Park, Manhattan Terrace, Matthews Park, Slocum Park and Yale Park.

Vanderveer Park, which was begun in the 1892 and was developed in five phases, was financed by the Germania Rail Co. and predated Prospect Park South, which is often referred to as the first such community in Flatbush. At the turn of the century, Vanderveer Park was significantly larger than all of the surviving Victorian Flatbush enclaves. The isolated Victorians around Sears in Flatbush were also part of Vanderveer Park.

Vanderveer Park was a development sponsored by Henry A. Meyer’s Germania Real Estate Company, which in 1893 purchased acreage from the Vanderveer Farm. At the time there was talk of a Flatbush annexation to Brooklyn (which happened in 1894) and Meyer set about covering newly-cut streets with ornate Victorian-era buildings. The name Vanderveer Park survives in the Vanderveer Park United Methodist Church at Glenwood Road near East 31st Street. And, there had been a Germania Place, connecting Campus Road and Flatbush Avenue north of Avenue H at Brooklyn College, but in 1959 it was changed to Hillel Place to honor the nearby Brooklyn College Hillel building, named for the first century AD Jewish religious philosopher. Lastly, Vanderveer Place remembers the name for a one-block street east of Flatbush Avenue and north of Avenue D.

I always associate Rogers Avenue with Prospect Heights and Lefferts Gardens, but there’s also a considerable Flatbush stretch, in which it slots in the place of East 27th Street; while the old Town of Flatbush had an East and West numbered streets scheme, with the streets running north and south with the “East” and “West” streets on either side of McDonald Avenue or West Street, there are occasional avenues running north to south that supplant the numbers.

Curiously, local merchants have slapped the name “Clarendon Meadows” in this neck of the woods. The name is one of the British-sounding names affixed long ago. Clarendon is also the name of an old-fashioned, blocky type font and a number of towns in the British Commonwealth and the USA bear the name as well.

I had no idea how huge the complex Flatbush Gardens was until it took me a good 15 minutes to walk through it from Nostrand Avenue to East 36th Street along Foster Avenue. The place is huuuge, as the commander in chief might say. It was developed from 1949-1950 and consists of 180 separate units containing over 2500 apartments. Among its former residents in Barbra Streisand, who lived here in the 1950s and attended Erasmus Hall High School on Flatbush Avenue.

A very faded sign indicates Flatbush Gardens’ old name, Vanderveer Estates.

Growing up in Brooklyn, I had heard of the Catherine McAuley Catholic girls’ high school but had no idea where it was (East 37th Street north of Foster). The school, which closed in its original incarnation in the spring of 2013 after 71 years, is now the Cristo Rey (Christ the King) High School, not to be confused with its much larger counterpart in Middle Village, Queens. The school was named for the woman who founded the Sisters of Mercy in 1831 in Dublin, Ireland after she inherited the equivalent of 1 million dollars from a former employer. As the entablature indicates it was once “Catherine McAuley Commercial High School” because many of its graduates entered the workforce.

Paerdegat Park, which makes up the entire block between Foster Avenue and Farragut Road between East 40th Street and Albany Avenue, has one of Brooklyn’s Dutchiest of Dutch names, a transliteration of paard gat, “horse gate.” Its original use in Kings County was for Paerdegat Creek, which one ran from about where East 31st Street and Foster Avenue would be laid out southeast into Jamaica Bay. In the 1920s its northern section was filled in and the southern end dredged to make it available for shipping as the Paerdegat Basin, which today runs only as north as Flatland and Ralph Avenues, where we today find the Bureau of Sewers, seen on this FNY page. The land was acquired by NYC for public park use in 1941.

Also: refer to the 1890 Kings County map again, and check the Flatbush Water Works at the approximate location of Foster Avenue and New York Avenue, located near the Paerdegat Creek (a.k.a. Bedford Creek) headwaters. The Flatbush Gardens complex would rise later at this location.

A selection of churches along Foster Avenue between Albany and Utica Avenues.

The preponderance of the word “jerk” in store signs in Caribbean-American neighborhoods (this one at Foster and Utica) may be confusing to some, but the explanation is simple. Jerk is a style of cooking native to Jamaica in which meat is dry-rubbed or wet marinated with a hot spice mixture called Jamaican jerk spice, and “jerk chicken” and “jerk pork” restaurants are frequent in these parts. The word comes through Quechua Native American and Spanish term charqui, “dried meat,” and can also be found in the snack called jerky. I found Jerk chicken scrumptious, though beware, mine at times had the chopped up bones left in and I had to be careful eating it too quickly.

I’m unsure if Hecht’s Hardware, Foster Avenue and East 53rd, is still open, but a small piece of original handlettered signage (all right angles) is peeking through.

Foster Avenue ends its eastern progress, in East Flatbush, anyway, at Kings Highway a block east of here. But that’s not all there is of Foster Avenue. If you head south on Kings Highway about a mile, past the LIRR Bay Ridge branch overpass (a very strange layout), Foster Avenue continues as a divided 4-lane road northeast into Canarsie. Much of it, until you arrive at about Remsen Avenue, is quite boring indeed as it travels through industrial and wholesaling wastelands, so I skipped that section and headed north along Kings Highway.

At Ocean Avenue, Kings Highway, which had been a busy shopping stretch although a conventional two-lane avenue in Gravesend, absorbs busy Avenue P’s traffic and becomes a busy, pedal-to-the-metal 6-lane behemoth, roaring northeast into Brownsville. Before 1924, though, this was a minor unpaved route, curving through farms and old houses from the Dutch Colonial era, ending at the now-eliminated Hunterfly Road in East New York. In the early 1920s, the city and Brooklyn, under boro president Edward J. Riegelmann, decided to respond to the auto age and greatly widen and expand Kings Highway, adding multiple lanes.

In the colonial era, this wasn’t even Kings Highway — it was another route called the Road to Flatlands Neck. Kings Highway comprised sections of what are now Flatbush Avenue and the current Kings Highway, which turned west and ran as far as Bay Ridge. Over time, sections of Kings Highway west of Bay Parkway were eliminated and Flatlands Neck Road became Kings Highway’s northeast extension in the late 19th Century. But it wasn’t until 1924 that the road truly began to come into its own.

In the shot above we see one of Kings Highway’s Twin double-mast octagonal poles. They are rarer now, but there are still pockets of resistance that include Kings Highway and Union Turnpike in Kew Gardens Hills.

Note the circled Kouwenhoven Station at the bottom of the map. This photo from around the same time shows the station — pretty much a shack by the side of the tracks. The LIRR Bay Ridge Branch was a passenger line until 1924, after which it was alternately elevated and placed in an open cut and became freight-only. I rode the line in 2009 and offered observations. The road that is planked as it crosses the line is today’s Kings Highway. Photo from the collection of LIRR historian Ron Ziel

Nearly a century after the passenger LIRR line closed, East Flatbush is still not served by mass transit rail (though its bus lines have a free transfer to subways). Periodically, there are plans floated for a new crosstown Brooklyn-Queens-Bronx transit line to be built on the line, but they are not universally lauded. Meanwhile, mapmaker Vanshnookenraggen has put together a fantasy map of what the subway map would look like if every rumored or fantasized-about subway line was ever built, though it does not include the proposed “Triboro RX.”

North of Foster Avenue on the east side of Kings Highway are a pair of streets with curious names that first appeared on maps in the 1950s. The first is Whitty Lane, which runs through to East 56th Street and features brick attached homes on both sides of the street.

The second is Joide Court, which dead ends (with a loop at the end of the street) in the midst of Clarendon Gardens, a seven-building post-war apartment complex fronting on Kings Highway, Avenue D and East 56th. The anonymous brick buildings resemble Flatbush Gardens referenced earlier.

The names could be that of the developer or in the case of Jodie Court, the son or daughter of one.

There’s one in every crowd. A homeowner on Kings Highway opposite Clarendon Gardens has added their own unique touch to one of the attached brick homes. This part of Brooklyn was mostly developed after WWII — yet, until the mid-20th Century it was interspersed with farmhouses dating to the Dutch Colonial era. Some survive, others moved to museums, while others were torn down.

The street grid of the Town of Flatbush was first laid out on paper in the post-Civil War era, but the streets weren’t built in these parts until the first decades of the 20th Century. Kings Highway runs across this grid at a very sharp angle; it came first, as colonial settlers might very well have used a Native American trail as its route. Here in East Flatbush, small unnamed green spaces fill the angles in spots. They look drab in December, but add a necessary touch of green in the warm months.

The intersection of Kings Highway and Clarendon Road, the former Avenue C, has an infrastructural relic of which few are aware. The westbound Clarendon has a short angled pathway that gets traffic onto Kings Highway, which motorists can use without getting stopped by a light.

The Department of Transportation doesn’t mark it but this is a remnant of the old Canarsie Lane that I talked about earlier (marked Canarsie Avenue in this 1929 Belcher Hyde map). The road dates back to the colonial era and before, and connects Flatbush and Canarsie. Portions of the road still exist including Cortelyou Road on the south side of Holy Cross Cemetery; a marked section of Canarsie Lane that runs past the Peter Claesen Wyckoff House, the oldest in NY State, at Clarendon Road and Ralph Avenue; and the aforementioned Canarsie Road which runs from avenue M and East 92nd southeast to Seaview Avenue.

If you look at an aerial view of East Flatbush, Canarsie Lane’s path is still quite evident!

Now a rarity in NYC, these “boulevard variations” on the classic Donald Deskey lamppost were used on medians of especially wide roads, such as Kings Highway and expressways around town. They haven’t been produced since the 1970s, and they have gradually been replaced over the years.

Sometime in the 1980s, the decision was made to place some extra-large, economy-size street signs on Kings Highway where it meets Beverley Road, Tilden Avenue and Snyder Avenue. Possibly, traffic studies showed that motorists could see larger signs better as they were speeding along Kings Highway. These large size signs did not catch on elsewhere in the city. In the 1990s, large signs with upper and lowercase letters were hung on traffic signals, Los Angeles-style

The truly massive Samuel Tilden High School, which opened in 1930, and the namesake Tilden Avenue are named for NY State Governor (in 1875-76) Samuel Tilden, a Democrat yet a Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed opponent. In 1876 he won the Democratic nomination for President, won the popular vote vs. Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, but lost in the Electoral College, in an election result similar to the ones in 2000 and 2016. The street was renamed in the 20th Century from Vernon Avenue. In addition, the apartment building where my family and I lived in Bay Ridge at 83rd Street and 6th Avenue is named Tilden Court.

Tilden’s house at 15 Gramercy Park still stands and a statue of Tilden, dedicated in 1926, can be found at Riverside Drive and West 112th Street.

In order to save the New York City government money during the Great Depression, Samuel J. Tilden High School, Bayside High School, Abraham Lincoln High School, John Adams High School, Walton High School, Andrew Jackson High School, and Grover Cleveland High School were all built from one set of blueprints. Muralists Abraham Lishinsky and Irving Block painted a gigantic work, “Major Influences in Civilization” in the school’s auditorium in the 1940s.

Occasionally Kings Highway will surprise you. On the right is a 2.5 story frame pre-WWII building fitting within the triangle formed by Kings Highway and East 55th Street. It shows up on this 1929 atlas plate.

This pair of signs on the northbound Kings Highway lanes at Church Avenue tells motorists that NYS Route 27, which runs along Linden Boulevard, is coming up next. NYS 27 was routed along Linden Boulevard beginning in 1934 when Linden Boulevard was built out to its current width.

When behemoths meet! The only place in Brooklyn where two 6-lane street level roadways intersect is at Linden Boulevard and Kings Highway, an intersection that did not exist until the 1920s, when Linden Avenue was extended east to Kings Highway from Flatbush Avenue. I had been under the impression that Linden Boulevard and Kings Highway were widened at the same time, and may have stated as much in earlier FNY pages. That wasn’t quite the case.

But the city wasn’t finished with Linden Boulevard! Just as the city of Brooklyn kept annexing towns and Greater New York absorbed Brooklyn, so Linden Boulevard was pressed on and on into Queens, with roads in Ozone Park, South Jamaica, St. Albans and Rosedale all renamed Linden Boulevard by the mid-20th Century. Even the former Central Avenue in Elmont was renamed Linden Boulevard up to its junction with the Southern State Parkway, where Linden Boulevard finally comes to its eastern end.

However, Linden Boulevard doesn’t run continuously. It goes in fits and starts in Ozone Park, where there are a couple of dead ends named Linden Boulevard. Period maps also show it merrily plunging through Aqueduct Raceway, which obviously didn’t happen. My guess was that the city once had grand plans to make Linden Boulevard a 6-lane roadway out to Nassau County, but political realities got in the way just after the work got started. It’s one of the most puzzling situations I’m aware of in NYC, as I haven’t run a cross the smoking gun of documentation to prove it. If you can point me in the right direction, do so in Comments!

Willmohr Street is another puzzler; it runs northeast from the Kings-Linden intersection 8 blocks to East 98th Street. Until the 1930s, maps show it as the western end of Newport Street, which now begins at East 98th and runs east into East New York. In fact, maps from the 1910s show it as Linden Avenue before it was turned into a Boulevard and rerouted. What all this shows you is that names were in flux before they were constructed and they were just lines on maps. But who was Willmohr?

Continuing along Kings Highway, at Lenox Road you find some more unexpected Deco (as I did on Avenue H in Part 1). This is somewhat the worse for wear after perhaps 80 years.

Oddly, on other wide NYC boulevards like Linden or Ocean Parkway, the street lighting is pretty unified, i.e. the DOT settled on one style and stuck with it, but Kings Highway is all over the place with double masts, single masts, cobra necks and even “boulevard Deskeys,” as we have seen. This is the 1980s version of the Twin double mast, used most frequently on expressways but rare on local streets.

Parking is apparently at a premium on the East Flatbush-Brownsville border. You can park your SUV but please, curb your dog and keep off the grass.

The East Brooklyn Community High School, Kings Highway and East 96th, features some interesting architecture (1970s, maybe?) rad murals at the front entrance.

From Comments: The East Brooklyn Community High School at 9517 Kings Highway (East Flatbush/Brownsville border) used to be the B’nai Israel Jewish Center. The arches in the front of the building were meant to represent the two tablets upon which the Ten Commandments were inscribed.

At East 98th Street, it looks like Kings Highway is about to sweep into Brownsville — but its northern progress is stopped cold here and its 6 lanes become a mere four and the road changes names to Tapscott Street. A block away, Tapscott’s 4 lanes make a swerve and traffic is delivered onto Howard Avenue, whose 4 lanes then connect with Eastern Parkway after 3 northward blocks. It’s a nifty bit of traffic engineering that follows the original path of the Road to Flatlands Neck. To me, though, it was odd to not call the 4-lane road Kings Highway at least all the way to Howard Avenue.

I would have plunged further — these are realms where I am not normally found — but the light and my feet were failing me, so I went for the nearest elevated subway stop. East 98th Street, under the el carrying the #3 and #4 trains, is the western edge of Brownsville.

Brownsville and East New York are neighborhoods of eastern Brooklyn delineated in great part by the Bay Ridge branch of the Long Island Rail Road. In the north, Brownsville runs from East New York Avenue, on the Bedford-Stuyvesant border, south to its border with Canarsie at the railroad; East New York begins at the railroad and continues east to the Queens line at Ozone Park, with the neighborhoods of Highland Park and Cypress Hills to its north and Jamaica Bay on its south.

Though Dutch immigrants had established some homes and farms in Brownsville and East New York in the 1700s, the area did not gel as a community until the early-to-middle 1800s. East New York was developed by John R. Pitkin, a Connecticut merchant beginning in 1835, while Brownsville is named for Charles S. Brown, who subdivided it in 1865.

Time to kick it in the head at the Saratoga Avenue station. But here you can continue along on Livonia Avenue, as Sergey Kadinsky will be your guide to NYC’s only street that is completely shrouded by an elevated train.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

1/13/17