“Cortlandt” is a common name in the various NYC street directories and gazetteers, either with a “Van” or without. The street is named for the family of Oloff Stevensen Van Cortlandt, who arrived from Holland in 1637 and became a brewer, with the family eventually amassing a great deal of property and influence. His sons Stephanus and Jacobus became NYC colonial-era mayors. Jacobus purchased the vast estate in the northern Bronx where he built a mansion that stands to this day, and much of the estate became Van Cortlandt Park. Several roads bordering the park or near it were also named Van Cortlandt.

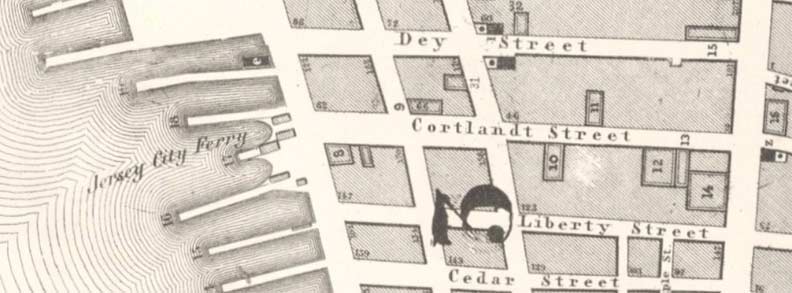

Since 1970 or so, Cortlandt Street has extended for only one block, between Church Street and Broadway. However, two subway stations, one BMT, one IRT, have stations located on Cortlandt Street. Why was Cortlandt Street considered important? The answer lies in its transportation connections. Since 1908, both stations have featured a connection to the Hudson Tubes that connect Lower Manhattan with Jersey City, Hoboken, and Newark. And, until mid-century, there was also a ferry that connected Cortlandt Street with the Jersey City waterfront.

Passengers could take ferries to Pennsylvania and West Shore Railroad stations in New Jersey and connect to lines that operated local and interstate service. However, a ferry at the west end of Cortlandt Street had been established much earlier, as early as 1764. Steamboats were in service as early as 1812, and reduced travel time across the river to less than 15 minutes. However, service was interrupted fairly regularly in the winters, which were somewhat colder then and ice regularly choked the river.

Additionally, there was a Cortlandt Street elevated train station at Greenwich Street until 1942.

Here’s a look at Cortlandt Street and Washington Street in 1908, a location that was demapped in the late 1960s as the old World Trade Center was built in place of all these buildings. A much closer look can be obtained at Shorpy, a site dedicated to selling old photos, but also reproduces them in large sizes with, thankfully, no watermarks. Based on that view, I can make these observations…

Looking at that image, we see the left side of the photo dominated by the Glen Island Hotel. A fire alarm and its indicator lamp and some derby-hatted idlers can be seen on the left. Further up the street are ads for the Gilsey House (Hotel) which is still there at Broadway and West 29th Street, and Omega Oil, an all-purpose liniment whose colorful ads can still be seen to this day in some spots. Further on, there’s an ad for Clysmic Water, the Poland Spring of its day. The company was based in Waukesha, Wisconsin and had some snazzy ads. Beneath it is an ad promoting the Broadway play The Witching Hour, which featured John Mason and ran from September 1907 to May 1908.

In the background we see one of the twin 22-story Hudson Terminal buildings, which some call the original Twin Towers. They housed offices of the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad which is now the PATH train. The tallest building on the right is the Singer Tower, housing offices of the sewing machine company. Designed by Ernest Flagg, the immense tower went up in 1908 and came down in 1967. It remains the tallest building that was demolished by design and not by terrorism. It was replaced at Broadway and Liberty Street by the rather nondescript US Steel Tower (now #1 Liberty Plaza) in the 1970s.

On the right is an ad for Virgin Leaf tobacco. Virgin Leaf, which could be smoked or chewed, originated in 1863 when David H. McAlpin purchased the trade mark from John Cornish. Ads for the brand, which could be seen rather frequently on buildings in Manhattan till fairly recently, also featured McAlpin’s name. The company, like others of its time, also distributed hand colored cards promoting the brand. Directly below the Virgin Leaf ad is one for Coca-Cola, which still uses the logo today.

Dooros Ice Cream, lower right, was no doubt a popular brand, but all trace of its existence has vanished from at least a cursory internet search.

Finally, at lower right, is the ticket office for the Pennsyvlania and other railroads. As we’ve seen, the Cortlandt Street Ferry whisked passengers across the river to railroad terminals on the New Jersey side.

Moving forward to 1925 or so, we see the Glen Island Hotel still there. If we could zoom in just a bit, we would see several storefronts given over to radio parts and radios in general. Broadcast radio programming began to take off in a big way in the 1920s, and networks still in existence today– NBC and CBS– had their origins at this time. ABC was developed later as an NBC offshoot. Many of the buildings are still the same, and the old 9th Avenue El was still shadowing Greenwich Street.

photograph by Berenice Abbott

Cortlandt Street looking west to the 9th Avenue Elevated station at Greenwich in the 1930s. By now, New York City’s “radio row” until its razing in the late 1960s. Dozens of wholesale and retail stores sold radios and electronic equipment. In that era radio was as important as television and later, the internet. Brand names like Heins & Bolet and Davega, forgotten today, were prominent on sidewalk signage.

Until 1942, the corner of Cortlandt and Greenwich Streets served double duty: there was an elevated train station above, and a subway station below. The el came first, as long ago as 1870, while the subway station, part of an extension of the IRT 7th Avenue Line south from 42nd Street, opened on July 1st, 1918.

After 1970, the Cortlandt Street IRT station opened directly into the underground complex of the original World Trade Center and didn’t have entrances on streets at all. In 2001, after the terrorist attack, the IRT Cortlandt Street station closed for the next 17 years. The reasons it took so long to reopen are myriad, but basically the area was a recovering war zone for the the first three years after the attack, and debris needed to be cleared out after the station itself was obliterated. Through service to South Ferry was restored in surprisingly short order, but there was no reason to rebuild IRT Cortlandt while construction work on the PATH station Oculus, as well as #3 and #4 World Trade Center between 2005 and 2014 was ongoing. The station reopened in September 2018 after those buildings were completed, and I took a look.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t around in the days when the original IRT Cortlandt Street mosaic designs were still on the walls. They were removed in a misguided modernization effort in the 1960s and 1970s when the original WTC was built, and a bland brick wall and generic Helvetica sign scheme was used thereafter. Here’s a shot of an original Cortlandt Street mosaic from NYC Subway that gives you a good idea what the station looked like originally.

We can see that the Cortlandt Street Ferry was selected as the representative mosaic design. The mosaic was either designed by Herbert Dole or by Squire Vickers, who served as the subways’ primary design chief from 1908 to about 1940. Hopefully the Transit Museum has one or two of these preserved — I think it does.

In recent years the Metropolitan Transit Authority has opened a number of new stations, such as at South Ferry, Hudson Yards (seen on this FNY page), Arthur Kill on the Staten Island Railway, and three new ones on the Second Avenue extension of the Q train. In addition a station renovation pilot program has been, or is in the process of, completely renovating stations such as 53rd Street and Prospect and Bay Ridge Avenues on the R train as well as all of the stations on the Astoria Line north of Queensboro Plaza; of those, 30th and 36th Avenues recently reopened.

Of the new stations listed above, in my layman’s opinion the only truly esthetically innovative stations are on the elevated Astoria Line, which are installing see-through, thick tempered plastic panels that open up the stations to a lot more sunlight than previously. However, other stations depend on a primarily white color scheme that gets somewhat monotonous. The new South Ferry station (which had to be rebuilt nearly from scratch after Hurricane Sandy flooded it in 2012) can’t compare with the old one, which was admittedly a few cars short of allowing ten cars to platform, but had a number of engaging quirks such as mechanical moving platforms, an oval station layout, and best of all, 1905-era Heins and LaFarge era terra cotta station name panels and bas reliefs. All of that is now closed off to the regular passenger; I hope the MTA can put a Manhattan branch of the Transit Museum there, though the idea hasn’t seemed to have been floated yet.

Always curious about the MTA’s new station offerings, I disembarked at Cortlandt Street a few days after it reopened. I was, again, underwhelmed immediately by the plainness of the station at the south end: plain white wall tiles, and columns painted gray.

However, the white-tile scheme does not extend for the entire station. Most of the walls on both platforms feature a bas-relief mosaic with raised letters — again in white, of course — known as “Chorus” and featuring language from the 1776 Declaration of Independence and 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights; the work was commissioned by MTA Arts and Design and was conceived by artist Ann Hamilton. New station lighting, while sufficiently bright enough for safety, is positioned to illuminate the new artwork.

The station includes new-style “countdown clocks.” While these have been in service on IRT lines for the better part of a decade. the new ones at Cortlandt Street are the first in the IRT to use LED lighting and a readout that looks like this.

Although it took 17 years to reopen Cortlandt Street, the station was not quite finished and work was still ongoing on the mosaic artwork as well as the staircases on the north end. However, these north end staircases open into what is still a construction zone amid the unfinished #2 World Trade Center and Ronald O. Perelman Center for Performing Arts.

I took a photo of the air vent here because Cortlandt Street, along with the IRT Grand Central Platforms, are unique in the system in that they recirculate cooler air into the stations to prevent them from becoming sweatboxes in the summer months. The pendant objects are security cameras.

I’d say the most innovative design at the new Cortlandt Street station is that the northbound side opens directly into the new, ribbed Oculus PATH terminal/shopping mall. The lengthy, arched entranceway looks like nothing else in the MTA.

I’m happy to have Cortlandt Street back — it’s modern, sleek, and looks like the 2010s, the era when it was built. I would’ve liked more of a nod to the station’s and region’s rich history, still. To me, like most of the newer stations, it’s an exercise in blanditude.

Back at street level, here’s 175 Greenwich Street, a.k.a. #3 World Trade Center, an 80-story glass-exterior tower 1,078 feet in height and designed by Richard Rogers. It was built between 2010 and 2017 with delays in financing and design pushing the project back, with advertising, management consulting and stock exchange tenants.

Me, I took note of the lamppost out front. Greenwich Street was pushed through the new WTC site, connecting its orphaned ends on the north and south. Since heavy construction is still going on at the north end of the complex, the road is closed there, and so no motorized traffic presently uses the route. I’d imagine traffic would be restricted even after construction is finished.

Even though standard issue octagonal lamps have been installed along Greenwich Street, the luminaire is the disk-like device that is usually found on the L-shaped poles found on lower Broadway and also on Jackson Avenue in Hunters Point. An interesting choice –I didn’t know these fixtures could be used on octagonal pole shafts. See the DOT Lighting Catalog for a full roster of NYC lamps.

A look north and south on the “new” Greenwich Street. Views include 123 Washington Street, a 570-foot luxury W New York hotel/condo, and the spindly exterior of the Oculus.

More glass at #4 World Trade Center, constructed between 2008 and 2013. Fumihiko Maki designed the 975-foot high tower which will serve as the headquarters of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which controls much of the transit infrastructure in the NYC metropolitan area except NY and NJ’s subways, buses and commuter railroads.

Like Greenwich Street, both Cortlandt and Fulton Streets were extended through the new WTC site, but for pedestrian traffic only. Cortlandt Street between Church and Greenwich Street was renamed Cortlandt Way.

Compare Cortlandt Way to the views of Cortlandt Street from 1908, 1920, and 1940, above. A bit of the old bustle is missing, no? Everything looks so sterile and anodyne. The old WTC was no bargain in that regard, either, with two vast towers standing in a large plaza, with most of the activity in the shopping mall in the basement.

Crossing Church Street, the aggressively Art Moderne 22-26 Cortlandt Street was constructed in 1933 [Walker & Gillette, architects] for the East River Savings Bank, established by attorney John Leveridge in 1848. The ERSB lasted over a century and a half before merging with Marine Midland Bank in 1995.

Only the extreme west end of Cortlandt Street near Broadway still has some of the flavor of the old, crowded streetscape of what must have existed in the eras of the photos at the top of the post.

That’s more like it! Some of the oldest buildings on lower Broadway can be found in the stretch between Cortlandt and Dey, though the upper floors are only still used in a couple of them. Most notably the 4-story Germania Building above the Century 21, built for the Germania Fire Insurance company in 1863. The name and date of construction are conveniently shown at the roofline. It’s one of Broadway’s handful of cast-iron front buildings. The insurance company went out of business in 1869, and the building has served myriads of tenants since, including Century 21, which obliterated the original bottom floor.

Compare the SW corner of Broadway and Cortlandt, a black-faced 743-foot tower that went up in 1973, replacing the Singer Tower. Cleary Gottlieb is the largest tenant with 11 floors.

I walked further–on Dey Street and West Broadway–but will save what I observed there for future posts. I’m still trying to make my Sunday feature pages shorter!

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

9/23/18