The Works Progress Administration Guide to NYC is a dense, 700-page volume with tightly-spaced type in a small but readable Garamond font, with a generous use of maps, art and photographs, describing New York City as it was in the 1930s. The Federal Writers’ Project, during the Depression years, put a lot of unemployed writers and photographers to work producing series of books describing various American locales; the New York guide is the most famous of the bunch, and has been reprinted a number of times since it was first issued, most recently in 1995.

The scope of this publication is fully described in Research NYC History. I can tell you that I first encountered it in grade school during my visits to the local library in Bay Ridge, where the first edition was on the shelves. In 1982, I obtained the Random House reissue, which featured new cover art but otherwise retained the original publication of 1939, with a new introduction by urban chronicler William “Organization Man” Whyte. The New Press issued it for a third time in 1995.

In late 2019, the online NYC Municipal Archives flooded thousands of tax photos from 1940 from all 5 boroughs onto the World Wide Web. Most were hurriedly done and were not artistic and scope; just for tax identification purposes. The photographers didn’t turn in Ansel Adams -level quality — they just got the job done as quickly as they could. (I would have enjoyed being a part of both the Federal Writers project and the tax photo initiative had I been around then.)

Since both the Archives 1940 tax photos and the WPA Guide are in the same era — produced only a year apart — the lightbulb went off in my cranium, and I decided to take some of the more esoteric references in the Guide and match them up with what I could find from the Municipal Archives. Sort of like that Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups commercials from the 1970s in which chocolate and peanut butter found their way to each other.

Francis Bannerman, 501 Broadway

A weakness of the WPA Guide — and it’s a doozy — is that the maps contain area highlights that are numbered. However, the corresponding numbers are not listed in the text, so you often have to go scurrying to the main index to find an item numbered on the map. I suspect it’s baked into the design with the desire being for the reader to absorb the whole text instead of cherry picking.

Anyway, Bannerman’s Museum is mentioned at 501 Broadway. It’s part of Francis Bannerman and Sons’ firearms firm, founded in 1865 by a former Civil War naval officer. The museum featured exhibits tracing the history of modern weaponry and at the time (1939) included a flag belonging to General “Lighthorse” Harry Lee; a flintlock that belonged to Napoleon I; and a guidon, or forked pennant, of the 7th US Cavalry in the Battle of Little Big Horn, which did not turn out well for General George Armstrong Custer.

Though the Bannerman Museum is long-gone, a rococo armory Francis Bannerman built on Pollopel Island upstate on the Hudson River still exists in ruined form, and has been a destination for generations of urban explorers.

Church Goods, Barclay Street

Back in 2007 I wrote about the shrinking Flower District and Sewing Machine repair districts, each located between West 23rd and West 28th Streets west of 6th Avenue. NYC formerly had a large number of what I call “fiefdoms” or concentrations of businesses all offering the same services or selling the same things. Some, like the aforementioned, or the large Garment wholesaling district, are still around, while others, like the Meatpacking District, have shrunk to ghosts of their former selves.

In the 1930s on Barclay Street between Church and Washington Streets there was a concentration of “ecclesiastical supply stores,” selling vestments, chalices, missals, and the like. It likely sprung up in association with St. Peter’s Church, one of the oldest Catholic parishes in NYC, established in 1786 with the present church building dedicated in 1838. Nearby were the downtown Washington Retail Produce Market and the “butter and egg district” along Duane Street, dealing in dairy products but also nuts; the recently shuttered Bazzini importing business was a part of that scene.

Only St. Peter’s itself now bears witness to the old “Ecclesiastic District.”

St. Nicholas Church, 155 Cedar Street

Constructed about 1820 as a private dwelling, this Greek Orthodox church stood in the shadows of the World Trade Twin Towers between 1970 and 2001 when the building collapsed during the terrorist attack on September 11 that year. Greek immigrants established St. Nicholas in the building in 1916. For may years, the church sponsored the “Rescue of the Cross” ceremony on January 6, when a small wooden cross was thrown into the freezing Hudson River to be rescued by some of the more youthful parishioners. The ceremony was later amended so the cross could be pulled to safety using a white ribbon.

Cost overruns and fiscal chicanery have the project to build a new St. Nicholas on the new WTC plaza in abeyance; an incomplete building stands as the project got started, but hasn’t been able to be completed.

Ye Olde Chop House, 118 Cedar Street

For many years this was the oldest restaurant in New York City. It was founded in 1800 so at 108 Cedar and later moved a few doors down to 118, and by 1940 it was fully 140 years old. In the 1970s, it spent its final few years at 111 Broadway (a.k.a.One Trinity Center) at Thames Street. Lost City has a postcard view of the interior.

Today, 108 and 118 Cedar are occupied by the mostly featureless High School of Economics and Finance.

Davega City Radio, Cortlandt Street

Beginning in the 1920s, Cortlandt Street between Church and Washington Streets was New York City’s “radio row” until its razing in the late 1960s. Dozens of wholesale and retail stores sold radios and electronic equipment. In that era radio was as important as television and later, the internet. Brand names like Heins & Bolet and Davega, forgotten today, were prominent on sidewalk signage.

FNY took a deep dive on Cortlandt Street in 2018.

United Fireworks, Park Place

In the 1930s, there was a concentration of retail and wholesale fireworks businesses along Park Place east of Church and along Church between Barclay and Murray. Then as now, legal fireworks were big business at carnivals, circuses and celebrations, especially around July 4. These shops first arrived in the 1880s, as ‘works were shipped across the Hudson from New Jersey factories.

In this photo, note the newspaper delivery truck, and on the right, the World’s Fair license plate; the Fair was held in Flushing Meadows in 1939-40 and again 25 years later, in 1964-65.

In the modern era, things have considerably quieted down along Park Place.

Sporting Goods, Chambers Street

Similarly, sporting goods, featuring everything from baseball bats to hockey masks to sporting rifles were sold in a concentration of retail businesses along Chambers between Broadway and West Broadway. The strip features plenty of restaurants these days, but a look on Street View revealed nary a sporting goods place.

Old Beekman

WPA Guide: “On the northeast corner of Gold and Beekman Streets is the Old Beekman, a tavern and coffee house where General Grant is said to have imbibed his favorite Peoria whiskey.” The Southbridge Towers housing project occupies the site today. Here’s a 1921 view with a painted sign indicating that the Old Beekman was established in 1827.

Olliffe Pharmacy, Bowery

The William J. Olliffe Pharmacy was established in 1805 at #6 Bowery off Chatham Square between Doyers and Pell, during the Thomas Jefferson administration, and remained in business, in the same spot, for over 175 years, finally succumbing in 1982. The Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 15, 1896, features the story of the venerable drugstore’s first 90 years in business.

Olliffe Pharmacy in 1896

Municipal Archives photo of Olliffe’s in 1940.

Olliffe’s a short time before it closed, in 1982. The address #6 Bowery still exists, but is occupied by a newer building, Abacus Federal Savings.

Peter Cooper House

Peter Cooper (1791-1883) was the industrialist-inventor whose conceptions resulted in the transatlantic cable, the steam railroad engine, and Jell-O. He established Cooper Union, the architecture, art, and engineering school still going strong in Cooper Square, Manhattan. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery; the site of one of his glue factories on Maspeth Avenue in Williamsburg is now a park.

#9 Lexington Avenue, at the southeast corner of East 22nd, was Cooper’s home for a time in the late 1800s. The entrance had two lamps at the doorway, a distinction usually reserved for NYC mayors: however, Cooper’s son-in-law, Abram S. Hewitt, was NYC mayor from 1887-1888. Cooper’s descendants lived in the building until 1938. The space is now occupied by the Park Gramercy, a high rise apartment building.

Teutonia Restaurant

158 3rd Avenue, between East 15th and 16th Streets, is listed in the WPA Guide as the Tutonia Restaurant, one of many halls, clubs, galleries and restaurants servicing the German population of the East Village in the early 1800s. The restaurant was marked by the “Germania Hall” neon sign in this 1940 photo. Nearby Scheffel Hall, which is still marked with ancient iron signage, was another such establishment.

What caught the Guide‘s notice, though, wasn’t the Teutonic history of the place, but rather its association with the United Homing Pigeon Concourse, reportedly the biggest racing pigeon organization in the country, which also met at the hall. Check the American Pigeon Journal, January 1921.

Lüchow’s

The south side of East 14th Street from Irving to 3rd Avenue is currently dominated by the bland NYU University Hall (with a Trader Joe’s on the ground floor), built in 1998 over the bones of old Lüchow’s (complete with ümlaüt) the grand old German eatery, a hangout for piano man William Steinway, Enrico Caruso, Cole Porter, O. Henry, Al Smith, and Victor Herbert; it was the Elaine’s of its time.

Luchow’s opened when Union Square was New York’s theater and music hall district. It consisted of seven separate dining rooms, a beer garden, a bar, and a men’s grill. One room was lined with animal heads; another displayed a collection of beer steins. Must have been a serious dining experience. Of course, when the city’s fortunes turned in the 1970s, so did Luchow’s. The restaurant shut its doors for good after a mysterious 1982 fire. [Ephemeral New York]

Next door is the massive marquee and frontage for the City Theatre, designed in 1909 by Thomas White Lamb. It was given an Art Deco makeover in the 1930s, but had closed by 1952.

Rhinelander Gardens

What a shame Rhinelander Gardens, formerly 112 to 124 West 11th Street just west of 6th Avenue, are no longer around. Similar to residences on some streets in Carroll Gardens, the houses were set back from the street, with fronts featuring cast iron balconies reminiscent of the ones in the French Quarter in New Orleans.

The buildings were designed by James Renwick, who designed the great Grace Church and St. Patrick;s Cathedral, in 1854. Thy take advantage of large plots permitted here by a triangular wedge in the street grid pattern. The Rhinelander family originally owned the plot.

The Gardens were gone by the 1950s, and the space is now occupied by PS 41.

Ohrbach’s

Nathan M. Ohrbach founded his moderately-priced department store in 1923 on East 14th Street near Union Square, pitting it in direct competition with the nearby S. Klein. From the beginning the store’s emphasis was on clothing and accessories. An early gimmick was even prices (opposed to the usual .97 or .99 prices).

In 1954 Ohrbach’s moved from the Union Square area to the locale I was familiar with it, West 34th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues, where it competed with Macy’s and Gimbel’s, which were long established on 34th Street. After expanding to California and New Jersey, fortunes for the store began to turn by the early 1970s, and the chain soldiered on until 1987.

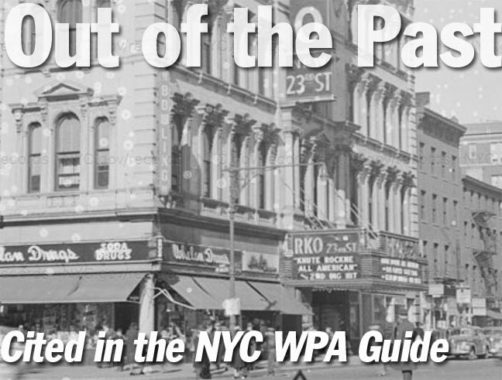

RKO 23rd Street

What in 1940 was the RKO 23rd Street Theatre had already reached an advanced age and was on its second life. The theatre,on the northwest corner of West 23rd Street and 8th Avenue, went back all the way to 1868, when Cincinnati entrepreneur Samuel Pike built an opera house and named it for himself.

After financier Jay Gould obtained the theatre, it was renamed the Grand Opera House. In 1938, RKO took over the building and hired Thomas Lamb Associates to convert it to a movie theater, renovating it completely to what we see in the 1940 Archives photos. The theater soldiered on until 1960, when it burned down a short time after closing for business. The space is now occupied by a low-rise building home to the Dallas barbecue restaurant. Cinematreasures has an earlier photo of it in more of its heyday.

Flower District, West 28th Street

The Flower District had its beginnings as far back as the 1870s, when flower dealers congregated near the East 34th Street Ferry. In those days the Long Island Rail Road had its western terminus in Long Island City and many goods, including those from the flower farms of Long Island, were shipped across the East River. In the 1890s, though, the flower wholesalers moved here, in an area concentrated on 6th Avenue between West 26th and West 29th, to serve the theater and entertainment area, which was here at the time, as well as nearby Ladies’ Mile (between 14th and 23rd) 5th Avenue hotels…and the brothels of the Tenderloin District, of which 6th and 28th was the epicenter.

The Flower District is now pretty much constricted to West 28th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues, as well as a few spots on 6th south of West 29th. I first stumbled on it when I had an editorial job at 5th Avenue and 20th and stumbled on it during my lunch break. A few years later, I was working a block away on West 29th, and went a block south to get away from it all.

Kauffman Saddlery, East 24th Street

This incredible stable building on East 24th Street east of Lexington Avenue was part of what was known as “Stable Row,” a district where horses, carriages and carts were rented out, even after the age of the horseless carriage began in earnest around 1915. According to the WPA Guide, the strength of the various horses for rental was gauged by running them up and down the block, hitched to wagons with locked wheels, by the whip.

The Kauffman Saddlery also functioned as a sort of museum, since it exhibited the minuscule carriage belonging to General Tom Thumb (Charles S. Stratton, 1838-1883), one of the shortest men in recorded history. But how did he find a horse small enough to pull it? Tom Thumb made a living by appearing in P.T. Barnum’s museums; in fact, he made quite a bit of money and even helped Barnum out of financial difficulties. At his tallest, he was 2’11.” The coach is now on display at the Witte Museum in San Antonio, TX.

United Dressed Beef

Turtle Bay, in the East 40s and 50s from Park Avenue east to the East River, likely takes its name from a Dutch term meaning “bent blade,” probably referencing the shape of the shoreline. It is somewhat hard to believe it now, but along the waterfront slaughterhouses had to be razed in the 1940s to make way for the United Nations complex on 1st Avenue. These days it’s a residential neighborhood prized for its peace and quiet — longstanding residents have included Katharine Hepburn and Irving Berlin.

One of the East Side meatpacking plants was United Dressed Beef, on 1st Avenue and East 45th Street. There were slaughterhouses elsewhere around Manhattan, too: West 39th Street between 9th and 10th Avenues was formerly sub-named “Abattoir Place,” and you know about the old West Side Meatpacking District that has become a shopping, dining and museum mecca.

5th Avenue Finlandia

Both of NYC’s strongholds for Finnish immigrants have just about disappeared. Finns joined other Scandinavian immigrants in Brooklyn in the early 20th Century, because of then-plentiful jobs on the docks on Brooklyn’s East River front, as so many imported goods were shipped in and out from there; the work has largely moved to area container ports, and Brooklyn (and Manhattan’s) shipping has largely gone away.

While Danes and Norwegians gathered in Bay Ridge and Sunset Park, Finns lived in northern Sunset Park, north of the park itself on the side streets between 7th and 8th Avenues. A couple of traces of that era remain. The the cooperative apartment building was conceived there, and some of the buildings are still in place; above one doorway is inscribed the Finnish phrase alku toinen (Beginning II); alku I was in stenciled goldleaf on an adjoining building, but it has since disappeared.

A second Finnish neighborhood existed in Harlem in the early 20th Century, concentrated on streets between 5th and Lenox (now Malcolm X Boulevard) in the upper West 120s.

There were jewellery shops, clothing stores and restaurants as well as a bakery and a beauty parlour.

Several Finnish clubs and associations were established; the most notable was Fifth Avenue Hall on the corner of 127th Street and Fifth Avenue. Starting in 1917, it formed the headquarters of a local Finnish Socialist party, but many without political affiliation used its billiards room, library, restaurant and dance hall. Expats mingled here on weekends, and romances sparked; many met their future partners at community gatherings.

Among these couples were Anja and Mauno Laurila, who both moved to the US in the 1950s and met at a party organised by a mutual friend in Harlem. By the time Anja moved to New York, Fifth Avenue Hall had already closed, immigration was slowing down and Sunset Park had taken over as New York’s remaining Finntown; when the couple got married in 1958, they too relocated to Brooklyn. [This is Finland]

Fifth Avenue Hall, 2056 5th Avenue at West 127th, is now … cooperative apartments, but with no trace of its Finnish legacy.

Savoy Ballroom

Harlem’s best known musical venue was the Savoy Ballroom, 596 Lenox Avenue at West 140th Street. Some of the biggest names in big band and jazz played the Savoy including Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Benny Goodman, Jimmie Lunceford, Dizzy Gillespie, and Fletcher Henderson. The Savoy was owned by Jewish businessman Moe Gale, but operated by African American Charles Buchanan. It was in business from 1926-1958. A nondescript commercial building occupies the site today, and the Savoy’s former presence is noted only by a small plaque affixed to a park railing.

A long succession of dance fads were launched from the Savoy that swept the nation and overseas in response to ever changing music trends from dixieland, ragtime, jazz, blues, swing, stomp, boogie-woogie, bop to countless peabody, waltz, one-step, two-step and rhumba variations. Among the countless dance styles originated and developed at the Savoy were: The Flying Charleston, The Lindy Hop, The Stomp, The Big Apple, Jitterbug Jive, Peckin’, Snakehips, Rhumboogie and intricate variations of the Peabody, the Shimmy, Mambo, etc. [Savoy Plaque]

That’s it for today — since the WPA Guide encompasses NYC’s five boroughs, perhaps I’ll do future FNY pages based on the WPA Guide‘s coverage.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/29/19