I’ve begun to think about “stuff” lately.

Forgotten New York celebrated its 20th anniversary this year, and I didn’t start on it until 1998, when I was 40 years old. This was just a few years after the World Wide Web started getting really popular; had the internet been around in the 1970s, think of how large Forgotten NY would be by now. If you’re keeping score there are 3,715 separate posts, which consist of tens of thousands of images, if you estimate ten images per page (many posts have one image but many have 100!) To cut to the chase, I’m thinking about legacy. In the immediate offing, I’m covered by the Greater Astoria Historical Society, which will continue the hosting if I’m run over by a streetcar or something. Long-term? I’m 61 now (in 2019), and hope to do this as long as I’m physically able. My energy levels are still as good as ever — I do a lot of walking and bicycling, though I can’t walk 20+ miles a day like some friends (to my frustration).

How will Forgotten New York be remembered when it ceases everyday production? Well, as a photographer and chronicler of New York city infrastructure, I’d be honored to be whispered about in the same breath as photographers Percy Loomis Sperr, Eugene Armbruster, Edgar “E.E.” Rutter, and the anonymous photographers who shot every property in New York City for tax purposes; their work can be found in the New York Public Library archives and in the NYC Municipal Archives. Their photography was primarily documentarian over esthetic: there wasn’t a budding Ansel Adams in the bunch. For esthetics, you’d be advised to turn to Berenice Abbott, who deftly managed to combine both everyday chronicling and beautiful photography, having been influenced by the great Parisian art photographer Eugene Atget and by artists Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. I don’t aspire to Abbott’s artistry, but I certainly aspire to the great documentary powers the other photographers I mentioned were able to achieve.

Remember, photography was an expensive, cumbersome business for all mentioned above. I have a camera with a small, thin chip in it that can record over 1,000 pictures depending on its setting, as well as a portable telephone that has an excellent camera almost as an afterthought. Street photography has never been easier. As far as modern work goes there’s Matt Weber, one of the best New York street photographers, and for night photography the best I’ve seen is Mitch Waxman, who sticks mainly to western Queens, especially the Newtown Creek area.

A few years ago, I got my mitts on nearly 1,000 photographs taken all over Queens between 1929 and 1940 primarily as a method of recording recent street paving jobs. Thus, the focus is on roadways, either those recently repaved or are about to be repaved. Everything else seemed to be done as a sidelight though, as you’ll see, some fascinating building interiors were also recorded as part of the project. I have a somewhat busy weekend with a tour scheduled, so I thought I would take a few of these and scribble something about what I’m seeing in each.

164th Street at Jewel Avenue, looking north, July 7, 1936

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, a trolley line connected Flushing and Jamaica, running originally through the farms and fields of Fresh Meadows. The above image was captured at 164th Street and Jewel Avenue in 1936, just a few months before service ended in 1937. In short order, the tracks were pulled up, the weeds paved over, a center median added, and 164th Street became the fast and furious stretch we know it as today between Flushing Cemetery and the Grand Central Parkway.

South of Grand Central Parkway the trolley line veered off 164th and rode on its own right of way to a terminal on Jamaica Avenue at about 160th Street. In the decades since, most of this trolley route has been either eliminated or hidden pretty well, but the four-lane width of 164th Street is a legacy of the route. As you can se there was one lane of traffic on the east side of the street, with the rest taken up by trolley tracks. This photo was about a year before service ended, and the line seems to be in decline, with plants and weeds sprouting between the tracks. For more information see Stephen Meyers’ book, Lost Trolleys of Queens and Long Island.

In the photo, the lengthy building seen on the right distance is still there in 2019.

Jewel Avenue is an unusual named street that runs from Forest Hills across Flushing Meadows-Corona Park all the way to Fresh Meadows. It’s the only remnant of a group of streets east of Queens Boulevard in Forest Hills named in alphabetical order that turn up on maps from the early 20th Century. The streets in sequence were named Atom, Balfour, Chittenden, DeKoven, Euclid, Fife, Gown, Harvest, Ibis, Jewel, Kelvin, Livingston, Meteor, Nome, Occident, Pilgrim, Quality, Ruskin, Sample, Thurman, Uriu, Verona, Webb, and Zuni; it’s likely the streets were only on the planning boards till they were built mid-century, by which time they carried the numbers (68th Road, 68th Drive etc) they do today. I don’t know why the Jewel Avenue name was kept; it’s one of the few non-numbered streets, along with Northern Blvd. and Roosevelt Avenue, that cross Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

The above photo was taken by the Somach Photographic Company, which also did a large amount of work recording what NYC streets looked like in the 1930s.

Ocean Promenade (Rockaway Beach Boardwalk) at Beach 101 Street

I cropped out the date on this photo to get my optimum width, but again, it’s sometime in the mid-1930s in late April. The season is just getting started at Gobel’s hot dog and hamburger stand. Note the barrel that was used to dispense Hires’ Root Beer. Silex coffeemakers debuted in 1915 and merged with Proctor Electric in 1960, creating the Proctor Silex company, which merged with Hamilton Beach in 1990.

The photos have largely yet to see the light, but in October 2018 I walked the length of the Rockaway Beach boardwalk, which aside from a short section by Riis Park near the Marine Parkway (Gil Hodges) Bridge, runs continuously from Beach 126th to Beach 9th Street (numbered streets on the peninsula get bigger from east to west). In 2012, Hurricane Sandy did a number on the old wooden boardwalk and it needed to be rebuilt virtually for its entire length. It’s now a state of the art seaside walk, but at the loss of the old “boardwalk” feel as synthetic materials were used instead of good old wood planks.

What is also missing are boardwalk-side vendors like this; I have a wealth of photos depicting these stands which numbered in the dozens. What happened to them? The closure of the Rockaway Playland amusement park in the early 1980s didn’t help, and today, not one remains. Also: “Specifically [Robert Moses’] 1939 road to nowhere called Shore Front Parkway. As part of the construction, no businesses or dwellings were allowed within 200′ of the boardwalk and a lot of homes, businesses and about half of Playland.

Capitol Diner, Lawrence Street, February 18, 1932

This E.E. Rutter photo of a roadside railroad-car style diner was taken in an era when fast food franchises such as Starbucks and McDonalds did not exist. Yet it can be said that the Dunkin’ Donuts of the world are the direct descendants of such road food stands, which evolved into steel and chrome diners. Such diners are now themselves dying out, as their owners retire and developers prefer to build multistory buildings in their footprints.

Yet, these small diners, the earliest of which were located in decommissioned railroad cars, were nearly ubiquitous even in downtown areas in the 1930s and 1940s; they’re all over scenes in the Municipal Archives linked above.

In 1969, the Department of Traffic (now Transportation) decided to rename 122nd Street, College Point Causeway, Lawrence Street, and Rodman Street under the single moniker College Point Boulevard. a short stub still bears the name Lawrence Street in Queensboro Hill. You have to be a little careful with the labeling on these photos; the “College Point Causeway” moniker only applied to the current stretch of College Point Boulevard on the diagonal stretch between 26th Avenue and the Whitestone Expressway; south of that, the bulk of the road was called Lawrence Street and that’s where this photo was likely taken.

On the ads, the Willys-Knight Company produced autos between 1915 and 1933. Willys, named for John Willys, developed one of the first “jeeps” used in World War II and the brand name survived until the late 1950s and a series of mergers. The Whippet was a popular model named for the racing dogs, in production between 1926 and 1931. And,

The Scranton & Lehigh Coal Company was one of Pennsylvania’s large coal companies, supplying the Northeast with anthracite and other coal products. The engines that powered Brooklyn ran on coal; everything from heating homes and apartments, to heating the offices, schools, and churches of the borough, to the huge boilers that powered the many factories in the city. Coal was the fuel that kept it all going until well after World War II. Even today, a coal furnace still turns up here and there; they were long lasting, powerful, but simple heat producers. [Brownstoner]

“Theater building,” Lawrence Street, February 19, 1932

Another Rutter photo from the same period, also labeled College Point Causeway, shows a former domicile that has been turned into a billboard for several local movie theaters and the features playing at the time.

On the top floor are bills advertising the Taft Theatre, opened on Main Street in 1917 Flushing and renamed after President William Howard Taft, who passed away in 1930. It was a first run theater, but could not compete with the nearby RKO Keiths and Prospect Theatres, and closed in 1955. Both the Keiths and the Prospect survived until the mid-1980s: the RKO Keiths shell building is still on Main and Roosevelt Avenue, awaiting redevelopment. The Loew’s Valencia in Jamaica has been a church for several decades, but its near-phantamagorical detail has been preserved.

As far as the features go, The Champ was a 1931 film directed by King Vidor about a broken-down boxer played by Wallace Beery (who won the Best Actor Academy Award) and his son, played by Jackie Cooper, who had a lengthy career: he played Daily Planet editor Perry White 47 years later in the first Christopher Reeve Superman. Little-remembered today, Marie Dressler earned a Best Actress nomination in Emma.

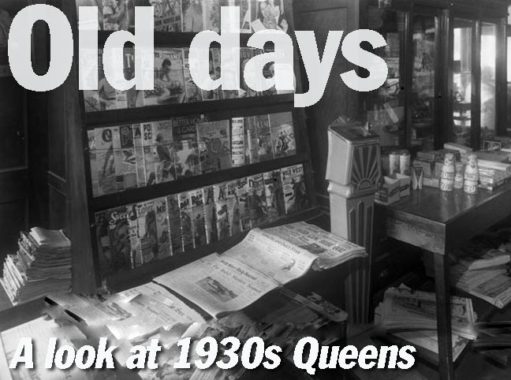

Newsstand, Cross Island Boulevard, July 22, 1938

This photo is slugged “Cross Island Boulevard” which is the former name of Francis Lewis Boulevard; when the Cross Island Parkway was built in the late 1930s, Cross Island Boulevard was renamed shortly afterward to avoid confusion.

Depicted is a typical newsstand of the period. The top shelf is full of romance and movie magazines, few of which survive today. Titles such as Popular Science, Better Homes and Gardens and Good Housekeeping are still in business today, but none of the newspapers shown, The Long Island Daily Star, The New York Sun, and the North Shore Daily Journal, are. The New York Sun was revived as a daily in the 2000s and still exists in online form.

Laurel Hill Boulevard and 47th Street, March 28, 1938

Nothing in this photo remains; the buildings on both sides have long been razed, and Laurel Hill Boulevard is now the service road on either side of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Changes were soon to come to this placid scene as the first Kosciuszko Bridge was spanning over Newtown Creek and the BQE was planned to connect Brooklyn and Queens. Once in Queens, the BQE was slated to follow the diagonal route of Laurel Hill Boulevard between the creek and Queens Boulevard, whereupon it would turn north to fork into two sections at Grand Central Parkway.

Laurel Hill Boulevard, named for a small neighborhood in Queens between Calvary Cemetery and 50th Street north of the LIRR Montauk tracks, dates back to the colonial era when it was paved with shells and known as Shell Road. It skirts the right end of Calvary Cemetery before following the BQE to Queens Boulevard.

James Gilder Bar & Grill, March 30, 1938

The James Gilder bar was located in one of the buildings depicted in 1938 that would soon give way to BQE construction.

Interborough Parkway, Cypress Hills Cemetery, January 27, 1932

The Jackie Robinson Parkway along with the Grand Central were the first of NYC’s “parkways” providing express (more or less) auto through-routing built within New York City. The “Jackie” unusually begins at the confluence of Jamaica and Pennsylvania Avenues in East New York, twisting through a convoluted route through the “cemetery belt” and Forest Park at the Brooklyn-Queens border, meeting the Grand Central at Flushing Meadows.

Here it is pictured as it was constructed in Cypress Hills Cemetery on January 27, 1932 in an E.E. Rutter photograph. Rutter chronicled the “Jackie,” which was called the Interboro Parkway until 1997 when it was renamed in honor of the first African American major league baseball player, who himself is interred in Cypress Hills. The parkway was rebuilt to handle modern traffic volumes from 1987-1992, eliminating the last traces of the original railings and overpasses seen here.

Metropolitan Beer Gardens, Metropolitan Avenue at Union Turnpike, June 28, 1933

Before the Interborough Parkway opened in 1935, narrow, two-lane Metropolitan Avenue was one of the main traffic routes connecting the Brooklyn waterfront and Jamaica. It was constructed as the Williamsburg and Jamaica Turnpike during the James Madison presidential administration in the 1810s and renamed Metropolitan Avenue after the Civil War. Union Turnpike (its name suggests it was originally tolled, as Metropolitan avenue had been) is a somewhat newer route and remained incomplete until the early 20th Century as an extension of Union Avenue, originally a short route in Glendale.

In the early 1930s, the Interborough Parkway was under construction, paralleling Union Turnpike for a portion of its route. No trace of the Metropolitan Beer Gardens exists today, and either the parkway construction or Prohibition (repealed in December 1933) may have done it in; beer gardens around town either went the speakeasy route or sold “near-beer” containing less than 0.5% alcohol by volume.

PS 63, October 30, 1929

Public School 63, which still exists today in a newer building (a massive edifice at Sutter Avenue between 90th and 91st Streets in Ozone Park) is pictured in a 1929 photo by E.E. Rutter. Though it’s slugged “Linden Boulevard” I can’t be sure it was located on that street as in the early 20th Century, Linden Boulevard, which has its origins miles to the west in Flatbush, was extended east through Queens in a halfhearted fashion; today Linden Boulevard exists in a number of separate pieces in Ozone Park, regaining traction for good in South Jamaica, where it runs continuously into Elmont in Nassau County along the former route of Central Avenue.

I suspect this photo was taken on Old South Road which decades ago was renamed in sections as Pitkin Avenue and Albert Road. Indeed, the present PS 63 is called the Old South School, which might cement it for you.

Soda Candy, Rockaway Beach Boulevard, April 26, 1938

Though Rockaway Beach Boulevard was rerouted in the 1970s a block north of this location and given extra lanes, a short, one-block stretch was left over and actually this portion of the road still exists. One thing you notice about this corner grocery is the Meadow Gold Ice Cream “privilege sign” in which a company would pay for a sidewalk sign, provided its product was prominently shown on the sign (several Coca-Cola signs around town in this category still exist. Meadow Gold, which also distributes other dairy products, is still found in several parts of the country.

Smith Brothers Ice Cream, Ditmars Boulevard and 23rd Avenue, East Elmhurst

One such Coca-Cola “privilege sign” can be found at this roadside grocery at Ditmars Boulevard and 23rd Avenue near Glenn Curtiss Airport, now LaGuardia Airport. In the forefront is a placard for Smith Brothers Ice Cream, a popular brand in the early 20th Century. This brand was not originated by the bearded fellows on the cough drop boxes, but company scion Richard Smith developed the Früsen-Gladjé, Chipwich, Eskimo Pie and other dessert brands.

Van Wyck Expressway at 95th Avenue, September 7, 1934

The furiously mustachioed Robert Anderson Van Wyck was the first mayor of Greater New York, serving from 1898-1901. His involvement with American Ice, a monopoly in the necessary commodity before the age of universal refrigeration, cost him his political career. Nonetheless when a major route was built between Jamaica Avenue and Rockaway Boulevard in the early 20th Century it received the name Van Wyck Boulevard. The Van Wyck family was prominent in Jamaica since the Civil War era; but the mayor’s family were originally from North Carolina.

In the early 1950s, NYC traffic czar Robert Moses built the Van Wyck Expressway along this route from Flushing Meadows south to Idlewild, now JFK Airport. The west side of Van Wyck Boulevard was retained, while everything on the east side was demolished; the buildings seen on the right side of the photo at 95th Avenue still stand. Since hundreds of residences were retained this is one of the few Expressways in NYC that have numbered addresses.

Van Wyck likely pronounced his name with a long “why” but today, most locals use the WICK pronunciation.

Lawrence Street (College Point Boulevard) at 36th Avenue, February 18, 1932

The Flushing Main Street station is so-called because there used to be a Flushing Bridge Street station located on the Long Island Rail Road Whitestone Branch, which operated from the mid-1800s to 1932, branching from the Port Washington line at Flushing Meadows and running north and east to Whitestone Landing at the East River at 152nd Street. After the LIRR unsuccessfully tried selling the line to NYC to operate as a subway line (presumably a connection would be made to the Flushing Line, today’s #7 train) the LIRR shut it down for nonridership.

This photo shows the branch as it crossed Lawrence Street, now College Point Boulevard; the Flushing Bridge Street station was just east of here. When the tracks and signals were cleared away, the one-block stretch of King Road would replace them.

Gas station, Whitestone Parkway, July 27, 1937

Among the items seen are a coin-operated public telephone, a Gulf calendar, and an ad for the upcoming World’s Fair to be held in Flushing Meadows in 1939. The Parkway gained expressway status some years after the Whitestone Bridge opened in the mid-1930s.

I’ll get back to recent photos — but from time to time, I’ll be showing some of these classics to indicate how much has changed and how much has stayed the same. You can find much more in the book I wrote with GAHS, Forgotten Queens.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

5/19/19