Your boy has bronchitis two weeks after receiving a second Covid shot, so I’m taking it easy. Instead, it’s time for another Sunday with Sergey Kadinsky…

By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

Queensboro Bridge is the only toll-free crossing between Queens and the island of Manhattan, so it’s not a surprise that the traffic here can be sluggish during rush hours. Passenger vehicles have the option to use the upper level, where trucks are not allowed. Its views of the city have been used in film montages as long as the bridge has been in operation. Less documented are the approach ramps to the upper level that have the appearance of a miniature highway. The furthest ramp from the bridge begins at Thomson Avenue, which used to run deep into Queens but was mostly absorbed into Queens Boulevard. The remaining piece of Thompson connects Queens Boulevard and Van Dam Street to Jackson Avenue, running across Sunnyside Yard.

The approach ramp here runs between condo towers and former factories, narrow enough for us to imagine how the expressway would have appeared had it been constructed in Midtown. The tall building with the phone number on it is Linc LIC, a rental tower built by Rockrose, the most visible of the builders that transformed Long Island City into an upscale high-rise residential community.

At 23rd Street, the miniature highway gets a second deck that connects the bridge to 21st Street. Its appearance here mirrors the elevated Flushing Line #7 subway train that parallels it for one block. What really makes this system of ramps unique are its sharp 90-degree turns that force drivers to slow down.

The ramp was completed in 1931, but it took nearly a generation before it appeared in Hagstrom atlases, perhaps because it blocked views of the streets beneath it. In this image from the Municipal Archives, we see workers carefully painting the ramp. Around them are billboards naming the manufacturers in this neighborhood. At the time, Silvercup was not a film studio, but a bakery defined by its silver-color cupcake holders. Initially, the ramp terminated at 21st Street, and a decade later it was given a branch that reached to Thomson Avenue. Until 1942, the Second Avenue El trains also used the upper deck on its run between Manhattan and Queens. Following the removal of the train tracks, traffic lanes were expanded on the upper deck and a portion of the ramp on the Queens side was given a second deck.

Kevin Walsh does not drive, so while I have access to the deck of this viaduct in my car, he’d likely have more interest in what’s underneath. In this case, it’s a DOT storage yard. That’s often the case with such leftover parcels of land, where DOT, DSNY, and NYPD store their vehicles. One can imagine this space transformed into a linear park protected from the rain, but then where would city agencies park their trucks, tractors, and cars? They are essential to the workings of this city.

But if you wish to see a pocket park underneath this unnamed highway, there’s one at the split of Hunter Street and 26th Street that has plants, benches, and bike racks. In the background is the elevated Queensboro Plaza station serving the Astoria and Flushing lines.

At the corner of 43rd Avenue near this pocket park is Dutch LIC, completed in 2017. This upscale residential tower has triangular trusses on its ground floor that pay homage to the industrial history of the neighborhood. There is also a functional reason for this design. Besides the acute angle of the street corner here, beneath it is the R train tunnel that snakes around Queens Plaza. This truss distributes the structure weight away from the corner where the subway tunnel makes deep foundations impossible. The building’s name is in tribute to the nearby Dutch Kills stream and the area’s first colonists.

Prior to Dutch LIC, this corner hosted a rowhouse and a single-story office of Asbestos Workers Union Local 12, which had a charming mural honoring its members. The birthplace of Labor Day, NYC earned its reputation as a “union town.” Their center of activities is in LIC, where many labor unions have their offices. My first union job was during college, as a Gray Line tour guide, which is affiliated with TWU Local 225. At my city job since 2014, I’ve been a member of CWA Local 1180 and SSEU Local 371. I’ve also resided for eight years at Electchester, which is associated with IBEW Local 3. I take pride in my union membership!

Speaking of buildings with triangular edges, no two sides at the “meticulously-designed” Bevel LIC on 42nd Road appear the same. Its designer, the architectural firm ODA, has buildings across the city in its portfolio, along with projects in Canada, Israel, Russia, and Korea, among other countries.

A block to the west of Bevel is LIC’s cousin of the famous Starrett-Lehigh Building, with its wraparound windows and orange brick floors. In this neighborhood of labor union offices, it’s an ideal location for the Apex Technical School, where one can receive training in auto repair, welding, construction, HVAC, and plumbing. This is where blue-collar careers are celebrated. For many years, Apex had television ads featuring Neil Elliott, a bald middle-aged pitchman with a mustache. His appearance resembled my father, who was also a trained car mechanic before he switched gears to become a programmer.

[I seriously regret not learning a practical trade. –Ed.]

I returned to Linc LIC, the building with the phone number to take in the view of Midtown and the Queensboro Bridge from a 20th floor apartment. For now it is unobstructed, but I can imagine in the near future when more towers will sprout between this window and the East River, and then the value of this apartment will diminish a bit.

Returning to the street, I checked the sundial monument at the gore of Crescent and Hunter Streets. Kevin first reported on this humble memorial in 2009. Its gnomon is gone. Beneath it are plaques with four heroic individuals. Maria Hernandez, the Bushwick resident who was killed in 1989 fighting drug traffickers, and Brian Watkins, the Utah tourist who lost his life in the subway in 1990 fighting off muggers attacking his family. Hernadez also had a park in Bushwick named for her, and Watkins has tennis courts carrying his name at East River Park. The other two didn’t make the national headlines. I couldn’t find anything online about educator Joseph E. McGrath. As for surveyor Vincent C. McNeill, the City Record notes that he died in 1944.

The triangular merging of Hunter and Crescent Streets is matched by the CUNY Law School building, which has a rounded corner on its south side and a triangular slice corner facing Crescent Street. Previously located on the campus of Queens College, the law school arrived at its new LIC site in 2012, in a postmodern facility designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox. One of its pluses is proximity to the historic LIC Courthouse, and being one subway stop from Midtown.

Next to the law school is Skyline Tower, which constructed a new entrance to the Court Square station for the public. Three subway lines converge here: the Queens Boulevard line (E, M), Crosstown Line (G), and the Flushing Line (7) above them. Each line used to have its own station, which were later united by transfer tunnels and combined under a single name.

On 23rd Street beneath the elevated tracks are a set of row houses with stoops and ornate fences, that predate the construction of the subway line. One by one, such structures are facing demolition as glass box towers take their place across this neighborhood.

Looking west on 44th Drive, we see the contrast in design between these turn-of-the-century walk-ups and the luxury glass building next to them. This boxy beauty replaced a set of small buildings that included the office of Sheet Metal Workers Local 137. A couple of blocks to the south, Teamsters Local 808 also gave up its office building in 2017 to a luxury condo developer.

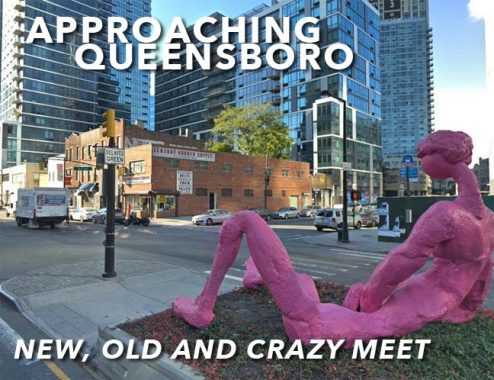

Eager to see something familiar in LIC that has not yet been knocked down, Century Rubber Supply still commands the corner of Jackson Avenue and 43rd Avenue. Jackson was given a green median a few years ago, along with a public sculpture, Ohad Meromi’s $515,000 Sunbather, installed in 2016 amid much outcry.

At 44-28 Purves Street is The Forge, a self-described “village-in-a-building” that seeks to include as many amenities as possible inside this 386-foot tower. In a nod to the local graffiti scene, one mural-covered wall from this site was preserved in the lobby. This concept is also found at 5 Pointz LIC, another luxury tower built on the site of the city’s best-known graffiti-covered factory, where the lobby serves as an art gallery.

One industrial relic that still commands attention on Purves Street is the Sculpture Center, which lovingly preserves the brick interior of this former trolley repair shop. It is one of the city’s lesser-known museums, and being on a dead-end street in the shadow of apartment towers contributes to the feeling of being an art insider when visiting this institution. There’s a lot of history in LIC concerning art, industry, and organized labor.

[I also have a supply of new photos in the Queensboro Plaza area; I walked there from Sunnyside through Calvary Cemetery recently. I plan to feature them soon, but the coughing will need to stop. –Ed.]

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

4/18/21