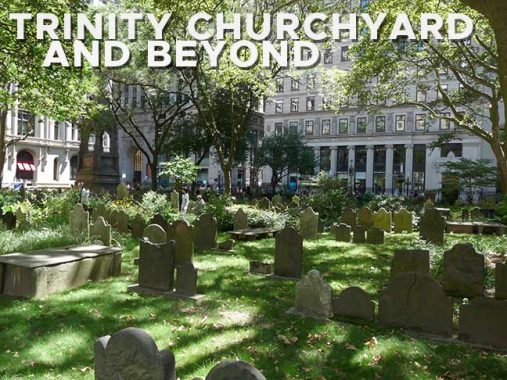

On a sunny late July 2022 Sunday, I decided to check out Trinity Churchyard and Broadway. I really had not spent any length of time there in a decade and certainly not since the Pandemic. Over the years I have actually been in, and conducted more tours in, Uptown Trinity Cemetery in Washington Heights, and my visits to the original flavor downtown have been relatively few. When I worked at Macy’s (2000-2004), we also had to work Saturdays during the holiday season and I recall one bleak December day when I took the train downtown and stalked around the churchyard on my lunch hour. I think overcast skies and relatively fewer people around is the best time to see Trinity Churchyard, and visible proof of that can be seen below.

Probably for security reasons, the old stones are more strictly guarded than in the past, with chain links completely lining the pathways; in other words, you can’t go on the grass anymore, making it tough to photograph inscriptions on stones that are angled away from the paths. I suppose there was an uptick in vandalism, forcing Trinity Church to do that.

The first mention of Trinity Churchyard as a burial ground was in 1673, over twenty years before the first Trinity Church was built from 1696-1697 when a small group of Anglicans living in Manhattan petitioned Governor Benjamin Fletcher for approval to purchase land for a new church. Approval was granted and the petitioners purchased land for the new church from the Lutheran Congregation in Manhattan.

That first church was burned down during a 1776 fire begun by invading British forces. The second church was built between 1788-1790, surviving another great fire in 1835, but was found to be inadequate for the needs of a growing body of worshippers, and so the third church, the neo-Gothic structure designed by Richard Upjohn, was consecrated in 1846. For many years, it was the tallest building in the city. The adjoining memorial chapel built from 1912-1913.

Until the Revolutionary War there were about 160,000 in the Trinity Cemetery churchyard. However, during the fires many tombstones were destroyed and others rendered unreadable.

Richard Churcher (1676-1681), the stone on the left in the first photo, died 16 years before Trinity Churchyard was incorporated. He is buried in what became the north churchyard. There are many icons that symbolize the shortness of life on his gravestone: a skull and crossbones, a winged hourglass, an imitation of a seventeenth-century English bedstead carved at the top of the stone. His grave is the oldest surviving in Trinity Churchyard. A relative, Anne Churcher (above), was buried next to him in 1691; she died at age 17.

“Sacred to the Memory of Adam Allyn, Comedian. Who Departed this Life February 16, 1768. This Stone Was Erected by the American Company as a Testimony of their unfeignd regard. He Posesed many good Qualitys. But as he was a Man He had the frailties Common to Mans Nature.” Everybody’s a critic!

Adam Allyn arrived in NYC with his wife in 1758. He made his American debut in Philadelphia’s South Street Theatre on July 20, 1759 in “The Recruiting Officer.” He also played in NYC, making his first appearance at the Beekman Street Theatre in November 1761.

The American Company, organized in 1758 by David Douglass, is considered the first American professional theater company. On February 15th 1768, the day of Mr. Allyn’s death, he was advertised to appear at 6PM as Old Philpott in a farce entitled “The Citizen.”

You can see by the photo that the best time to visit Trinity is on an overcast day in the winter, when shadows of fully leaved trees don’t play havoc with reading the inscriptions.

Gravestone Evolution in America

Sidney Breese (1709-1767) was Master of the Port of New York and subsequently took up mercantile pursuits and was called “a popular and hospitable man and a merchant of integrity.” The inscription is unusual: “Made by himself/Ha Sidney Sidney/Lyest thou here/I here lye.” On many of these stones you see the “long s” that was popular in orthography in the 1700s.

Mary Dalzell (d. 1764),

“Here lies the Body of Mary/Wife of James Dalzell/Of this City, who departed/This Life March 20, 1764/Aged 28 Years, 4 Months & 17 [days]/Adiew my dearest Babe & tender Husband/the time of my departure is now drawing nearAnd when I’m laid low in the silent Grave/Where the Monarch is equal with the slave/Weep not my friends I hope to be at rest/to be with Jesus Christ it is the Best.”

Grace Frost (1772-1797)

Dr. Peter Huggerford (d. 1795, age 43), his wife and son.

Mary Jessop, who died at age 25 (the grave also has her daughter Mary who died at 25 days) and Sarah Jauncey, who died at 45. The second stone has a winged angel, frequently found on 18th Century stones.

“Here lies the Body of Wm. Carlile/Son of Jon. & Mary Handy/Born Febry. 2nd, 1759, Departed this Life/Dec. 28th, 1759.

“Sleep lovely Babe, since/God hath Call’d thee Hence/We must submit to his/blest Will and Providence.”

The father, John(?) Handy was a member of the Masons, hence the square and compass motif on the top of the stone.

Maryanne (surname is worn off) died age 22.

“My parents dear, who mourn and weep/Behold the grave wherein I sleep/Prepare for death, for you must die/And be entomb’d as well as I.”

John Bates (1730-1770). Note crossed bones; there was likely a skull above them at one time.

Caroline “Lina” Webster Schermerhorn Astor (1830-1908), a prominent member of the Astor family and matriarch of the male line of American Astors, set herself up as an arbiter of “who’s who” as “nouveau riche” personalities entered society in the post-industrial revolution America. Mrs. Astor felt that the people who became rich from railroads and newly mechanized industries did not have the social standing of the older, more established families.

Assisted by social arbiter Ward McAllister, she started in the winter season of 1872-73 to build up her list of socially prominent New Yorkers, therefore designating twenty five patriarchs, who would define society, by inviting to each ball of the season, four ladies and five gentlemen. In addition to the thereby convened 250 people, an undefined number of visiting guests, prominent people from other cities, and debutantes would be invited directly by Mrs. Astor.

The Patriarch Balls held at Mrs. Astor’s mansions would go on until 1897, whereas Ward McAllister would organize them only until 1892. Of the last of these balls, held in the winter season 1891-92, Ward McAllister gave a list to the New York Times. For the first time after many years of guessing, the public was shown the official list of Mrs Astor’s Four Hundred and thereby the names of society’s sacred inner circle. [raken.com]

Mrs. Astor was buried in Uptown Trinity with the rest of the Astor family, including patriarch John Jacob. However, in 1914, this prominent tower in Trinity Churchyard was installed in her memory.

The Trinity Parish Yearbook of 1912 explains the symbolism of the Astor Cross:

“It is especially appropriate and significant that so striking a witness to the religion of Our Lord should be lifted up beside the Mother Church and in the midst of the dense crowds and the great business interests gathered in the lower part of the city…

The design has been prepared by Mr. Thomas Nash. The idea embodied in it is the genealogy of Our Lord according to St. Luke, as indicated by the figures of Adam and Eve, and then working around the upwards the figures are as follows: Seth, Enoch, Noah, Shem, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Judah, Ruth, Jesse and David, the whole structure culminating in the Crucifix, the Figure upon it being that of the Ruling Christ. The figure of the Blessed Virgin bearing Our Lord as an infant in her arms is placed on the back of the Cross. On the base of the monument will be the text from the First Corinthians, “The first man Adam was made a living soul, the last Adam was made a quickening spirit.”

Albert Gallatin (1761-1849) was a longtime US Secretary of the Treasury and US Representative. One of the three rivers that gives rise to the mighty Missouri in the state of Montana was bestowed his name by explorer Meriwether Lewis. A very short street off the Fulton Mall in downtown Brooklyn is called Gallatin Place.

Alexander Hamilton was born in Charlestown, Nevis and arrived in New York at about age 18 (his date of birth is uncertain; it is either 1755 or 1757) to attend King’s College, now Columbia University, after clerking at several firms and attending the school that later became Princeton University. He was quickly swept up by the fervor for independence that was gathering steam in the colonies, and served with distinction in the revolutionary army, eventually becoming the chief of staff of George Washington and the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He would go on to co-write the Federalist Papers that promoted the ratification of the US Constitution, and then became the USA’s first Secretary of the Treasury; he founded the Bank of New York, the nation’s first national mint, and in a foray into publishing, the New-York Evening Post, still published today as The New York Post. Hamilton never lost his attachment to New York City and in 1802 built the first house he had ever owned in upper Manhattan, in what was then completely rural land, on a hilly 32-acre plot on what would become West 143rd Street west of Convent Avenue.

Over the years Hamilton had rebuffed requests for duels from those he opposed politically or thought themselves wronged, but when he assisted Aaron Burr’s victorious opponent in the NY State gubernatorial election in 1804, Burr, then the sitting Vice President, challenged Hamilton and was acceded. The duel took place on the morning of 7/11/1804 in Weehawken, NJ. Hamilton fired first and missed; it is unclear whether he meant to miss or not. Burr did not miss and hit Hamilton in the abdomen. Hamilton was rowed back across the Hudson where he died of his wound at a friend’s place in Greenwich Village. Burr’s name is in general disgrace, though he is thought to be misunderstood by some historians. Hamilton is buried here, in downtown Trinity Cemetery.

Robert Fulton. See this FNY page.

The Lawrences were a prominent family in the early days of Queens, and produced some historically significant figures…for example, it was Captain James Lawrence (1781-1813) who uttered the immortal words “Don’t give up the ship!” while commanding the USS Chesapeake vs. HMS Shannon during the War of 1812. The Chesapeake was defeated; Captain Lawrence was killed; the war ended in stalemate. There are two extant Lawrence family cemeteries in Queens, in Astoria and Bayside. In Trinity, Captain Lawrence’s grave is in a prominent place by the Broadway entrance.

After leaving Trinity Churchyard, I headed up Broadway, but detoured to see the atrium at #60 Wall, a public space I never knew existed since I rarely enter buildings that aren’t specifically marked for public egress. The truth is, I’m usually thrown out or greeted with “CanIhelpyousir!?” The 60 Wall public space has been here since the 1980s, and is thought by architecture buffs to be a living fossil of 1980s design, as it’s mostly unchanged since it was built. I thought the climate controlled World Financial Center downtown was the lone space outside the New York Botanical Garden that you could see living palm trees in NYC, but they can also be found here. Until recently, Deutsche Bank called #60 Wall its HQ, but it moved to midtown, leaving the building mostly untenanted for now.

Update 1/26/24: This interior space will be redesigned and will no longer look like this.

The architect of 60 Wall Street, Kevin Roche, produced extremely detailed notes about the building. Writing by hand in 1984, he envisioned that its atrium — complete with water cascading over rocks, mounds of greenery and plenty of seating — would be “well-lit, bright and cheerful.” He also planned for “pockets of repose and quiet — refuges from the hectic pace of daily life in the district.” [NY Times]

For me my curiosity lay in the indoor subway entrance to the IRT 7th Avenue line Wall Street station (2,3), one of a few dozen around town. In 2014, FNY covered a particularly sumptuous one on Park Avenue South. I wonder if the station was always inside #60 Wall, before its atrium was built?

One of Manhattan’s most unique monuments gets stepped on thousands of times daily. William Barthman first set up a jewelry shop in the Financial District in 1884, and added a sidewalk clock on the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane in 1899. The clock was designed by Barthman and an employee, Frank Homm. When Homm died in 1917, no one knew how to maintain its singular design, and the clock was replaced with a more customary model in 1925 that’s been in place ever since.

The Barthman Clock has been attacked by vandals and trodden on for years, but it keeps on ticking with the help of an electric motor. An organization known as the Maiden Lane Historical Society set up a plaque in 1928 at Barthman’s depicting what Broadway and Maiden Lane looked like that year. In 1946, the NYPD estimated that 51,000 people stepped on the clock every day.

After moving up Broadway a few years ago, the jeweler now has an address in Brooklyn. But it made an arrangement with the current building to maintain the Barthman Clock, even though the unusual timepiece doesn’t have Landmarks Preservation Commission protection. The clock was not telling correct time in July 2022.

There is a short run of mid-size buildings on Broadway between Cortlandt and Dey Streets downtown — some of them have been around for over 150 years despite all the skyscrapering going on along Broadway north and south of them.

The Germania Building at 175 Broadway handily notes the date of construction on the cornice, as many late 19th Century buildings do. 1865 was the year the Civil War ended and Lincoln was killed. It was built by the Germania Fire Insurance Company; its cast-iron tower turns 157 in 2022.

The World Trade Center rose and fell just southwest of the Germania, and the Fulton Transit Center rose just to its north, but the Germania has fallen through the real estate cracks and carries on. Century 21, meanwhile, is planning to reopen its Cortlandt Street location in 2023, after being left for dead during the Pandemic in 2020.

St. Paul’s Chapel, Broadway between Fulton and Vesey, is hardly “Forgotten,” and as I write this on 9/11/22, I am aware that following the events of 9/11/01, it became a focal point of mourning for the victims of the terrorist attack. The church provided a round-the-clock relief ministry to Ground Zero rescue and recovery workers.

Following the September 11th attacks, it was a miracle that St. Paul’s hadn’t suffered any physical damage. Not even one window had been shattered. The building sat directly across the street from the World Trade Center yet survived unscathed. People started referring to it as “the little chapel that could.”

The church gave credit to a giant sycamore for saving it from damage. The tree stood in the corner of the property, taking the brunt of the debris. Only the church’s organ suffered serious damage, but it was quickly refurbished and put back to use. [911groundzero]

In the mid-1760s, NYC had sufficiently grown that the Episcopalian parish of Trinity Church began to expand uptown, and built St. Paul’s Chapel in 1766. When a giant fire broke out in lower Manhattan in 1776, most buildings in the area were destroyed, but a dedicated group of bucket brigaders kept St. Paul’s from burning down. Today, the new #1 WTC provides a 21st Century contrast to one of the few 18th Century buildings remaining in lower Manhattan.

Toward the north end of City Hall Park on Broadway south of Chambers Street, a look through the iron fence will reveal a rectangle marked by granite pavings. This is where the Bridewell Prison was in what is now City Hall Park. It was designed by Theophilus Hardenbrook in 1775. The jail, poorhouse and another building known as the “new Bridewell “were used by the British to house American prisoners of war. Construction was interrupted by the Declaration of Independence. The Bridewell, named for a London jail, was the most deadly of the prisons. It had no windows, only bars. The winter winds took the lives of hundreds of ill-fed patriots. Many thousands died in prison ships in the Harbor.

The sadistic William Cunningham was the provost marshal of the British jails. It is thought that Cunningham hung Nathan Hale, though the location of Hale’s execution is disputed. Cunningham is reported to have made a deathbed confession to starving 2,000 prisoners in the city as he sold their allotted rations for personal profit. He confessed to executing outright 275 American prisoners and “other obnoxious persons.” Women who visited the jails to speak to their husbands through the windows were beaten with canes and ramrods.

The Bridewell was used as a jail until its demolition in 1838. Granite blocks were incorporated into the new Manhattan Detention Complex (the Tombs). Its cornerstone can be found at the New -York Historical Society.

So nice I shot it twice is #287 Broadway at Reade Street, one of a number of handsome cast-iron front buildings found along the stretch north of City Hall. It was designed by architect John Snook and, as was fashionable in the year it was built, 1872, boasts a slanted mansard roof, a key element of French Second empite styling.

The Romanesque Revival #305 Broadway, at Duane Street, was finished by 1895 by architect William Hume for the Mutual Reserve Fund Life Association and built with a steel frame, revolutionary at the time. The indefatigable Tom Miller, Daytonian in Manhattan, has more. Though the first Duane Reade drugstore in Manhattan opened on Broadway between the two streets in 1960, this isn’t the original.

#319 Broadway at the NW corner of Thomas Street once had an identical twin across the street on the SW corner, both designed in 1870 by D. & J. Jardine. Over a century later that twin was replaced by a McDonalds, which was a mainstay for me when I was exploring this area in the pre-Forgotten NY era in the 1980s and 1990s. Next door, #321 Broadway dates to 1915 but looks much younger with a modern facade.

Yet another cast iron front special at #361 Broadway at Franklin Street, the James S. White Building was designed by W. Wheeler Smith and finished in 1882.

#427-429 Broadway, at Howard Street, was built in 1871 and designed by Thomas Jackson. It falls within the SoHo Castiron Landmarked District. If you have enough patience, read these Landmark reports: they’re really short histories of the neighborhoods that feature the landmarks.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

9/11/22