BY SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

SINCE the demolition of Shea Stadium in early 2009, Forgotten-NY has been documenting hidden train station signs that directed travelers to this former ballpark. With Citibank paying $20 million annually for the Citi Field name, there are a handful of honors for lawyer William Shea. Having campaigned to create a National League team in this city following the departure of the Dodgers and Giants, the Mets organization regards Shea as its founder.

The road bordering on the western side of Citi Field’s parking lot is Shea Road, an honor bestowed after the demolition of Shea Stadium. The city’s multiple agencies recognized that since its construction for the 1939 World’s Fair, this road did not have a name on the map and it needed one to direct motorists and report accidents. Having been informally known as Shea Road, the city made this name official.

The road runs from 126th Street, which is co-named for Tom Seaver, around Citi Field, to its southern end at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. There, Shea Road meets Meridian Road, which circles the central core of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. A few yards before this intersection, it passes underneath the LIRR Port Washington Branch, next to which is the Shea Substation that provides electricity to this train line. The MTA worked hard to erase Shea’s name from its stations; the 7 train and LIRR stations are known as Mets-Willets Point, but this hidden substation continues to honor Bill Shea. It is sandwiched between the tracks and the Olmsted Center, where Parks Department administrators, architects and engineers have their offices.

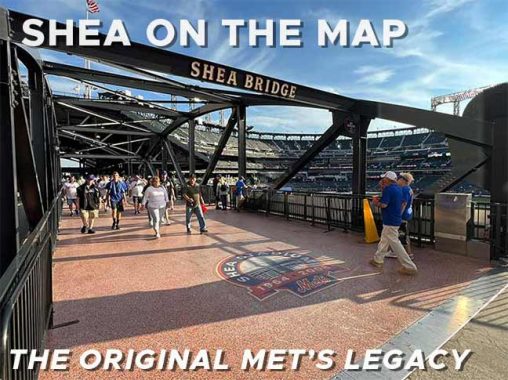

Citi Field is certainly not forgotten, but for a post-millennial stadium, it has its architectural quirks. Numerous fan websites have documented elements that commemorate Ebbets Field, Polo Grounds, the old Shea Stadium, the Home Run Apple, among other things. My favorite item at Citi Field is Shea Bridge, a miniature replica of Hell Gate Bridge behind the bleachers that has a plaque honoring Mr. Shea. The ballpark also has Shea’s name in a medallion on the outfield wall next to the retired numbers of notable Mets players.

Near the Shea Substation is the New Amsterdam Gate to Flushing Meadows. A stele next to this underpass lists heads of state who attended the World’s Fairs of 1939-1940 and 1939-1964. As the world was preoccupied with a global was in 1939, the only foreign leaders who traveled to this park for that fair were King George VI of Great Britain and Anastasio Somoza, founder of a political dynasty in Nicaragua. Among the attendees of the second fair here were three monarchs who later lost their crowns: Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran, Mwabutsa IV of Burundi, and Palden Thondup Namgyal of Sikkim. The last one had a personal connection to this city: his wife Hope Cooke lived in Manhattan before meeting the prince on a trip to India. Following the abolition of the monarchy and Sikkim’s annexation by India in 1975, Cooke returned to New York. She worked as a tour guide, wrote articles about the city’s history, and a book on her experience as a queen. I’m sure she’s familiar with Forgotten-NY.

This city doesn’t have a lot of traffic circles. Kevin documented some of them in 2019. Olmsted Circle honors the landscape architect of Central Park and Prospect Park, among numerous other parks. The building behind it is the Olmsted Center, the only building on Shea Road, but its address is listed as Roosevelt Avenue, as it has been since it was built in 1963 as a temporary office for the World’s Fair administration. In the past decade, the building was expanded and upgraded with sustainability and flood protection in mind.

We usually think that the only remaining structures from the 1939 World’s Fair are the Queens Museum and the Coney Island Parachute Jump. Behind the Olmsted Center is its garage, which was also built for this event. It is used by the Parks Department, unseen by the public. Behind the garage is the world’s largest tennis stadium.

The parking lot for Citifield is one of the largest in the city, bigger than the mega lots of Riis Park and Orchard Beach. Every couple of years we read of plans to build a casino, shopping center, or housing here. But this parking lot is public parkland leased to the Mets. In the off-season it is used for concerts and festivals. If it were to be developed, state law requires compensation by developing new parkland nearby.

I remember when Kevin published an essay on short roads that appeared as boulevards or highways. Shea Road has this look with its median separating the two directions. It is the most visible reminder of William Shea on the map.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

7/24/23