After chronicling Columbus Square at the Astoria Boulevard station on the Ditmars Boulevard Astoria el I found myself with a couple of spare hours on a brilliant August afternoon. Actually I had all the time in the world, as I was unemployed at the time. I never fully take advantage of a bad situation; when I was out of work the summer of 2011, I made a lot of forays but not as much as I could have, I imagine. But you can’t wish for too much time off.

Other than a walk down Ditmars Boulevard I have made only a few penetrations into Astoria north of the Grand Central Parkway over the years. It’s a change of pace from southern Astoria — one of the densest parts of the borough — and in many ways it resembles eastern Queens, with rows of attached houses and green lawns. There are historic interludes here though.

GOOGLE MAP: NORTH ASTORIA WALK

But first there is the matter of stoplights and lampposts.

Though NYC has used bulky guy-wired stoplight poles at major intersections since the fab Fifties, there is no Twin version of that post — so a different one has to be used when necessary, here where Astoria Boulevard meets the Grand Central Parkway at 32nd Street. The GCP is still nominally a Parkway here, but west of its junction with the Brooklyn Queens Expressway it’s Interstate 278/495, runs over the Triboro Bridge and feeds traffic to the Major Deegan and Bruckner Expressways.

Though the art of the painted wall ad may be“fading” from view in recent years, this is a new one on a blank brick wall facing the busy GCP traffic. Will it be allowed to remain for decades, fading out as it goes, or will another ad be painted on top of it?

Somehow the city missed replacing this vintage General Electric M400 that lights a GCP exit ramp. Introduced in 1958, these lights burn a greenish-white glow. In 2009, most NYC luminaires were replaced with a new version of the GE M400(seen at left in the above photo) and they missed very, very few.

Modest 2-story brick building on 32nd Street that missed the demolition for the GCP in the 1930s. I liked the bright red door.

Generations of maps from Hagstrom, Geographia,Rand McNally and dozens of other makes have been produced of this area of Queens and none, to my knowledge, ever show the stretch of 32nd Street between 24th Road and 24th Avenue, but it always has been as 24th Avenue is at the crest of a hill and the road was never built on it. Google Maps has corrected the error.

24th Road is one of those one-block Queens alleys I would take better note of if they actually had names. For example, before Queens streets were numbered it was called Cushing Place.

I rarely miss things like this. Stacked street signs like this in NYC are quite rare. In other cities they’re quite common but in NYC — not for nearly a century. It was done in NYC when street signs were considerably smaller, and ‘stacks’ persisted in Staten Island until the 1960s. For many years, different Queens communities had different genre of street signs, since Queens is really a grouping of small towns, the distances between having been long since filled by suburban housing tracts.

A look at the new park in the center of the block, atop the hill.

The sidewalk granting access to buildings on the east side of 32nd Street has to be accessed by steps.

Long flat building of a certain age on the west side of the street. Would like to know the story behind this.

A relatively unaltered building on 32nd Street just south of 23rd Avenue. The window lintels and roof corbelling are virtually the same as when built – over a century ago?

At 31st Street and 23rd Avenue the Astoria El terminates at the Ditmars Boulevard station, opened 7/19/1917. The station runs beneath one of the massive Hell Gate Arches, built from 1914-1917, that carry Amtrak and freight traffic into the Hell Gate Bridge. Here, the arch has been newly painted. As the NYCsubway.org page points out, the Ditmars Boulevard station has a protective platform canopy, but only under the arch!

31st has previously been known as Debevoise Avenue and 2nd Avenue.

The east side of 31st Street features a mural by the students of the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts, a new complex in the Kaufman Studios originally conceived by native Astorian Tony Bennett, who appears on the mural.

The school’s program consists of a rigorous academic curriculum and pre-conservatory studio education in one of the following art forms: instrumental music, vocal music, fine arts, drama and dance. Students are able to accomplish academic coursework and the intensive study of an art form in three or four years through an extended day format.

31st and Ditmars are the main shopping streets in northern Astoria. Rosario’s Deli (which is also a pizzeria) receives mostly 4 and 5 stars from yelp reviewers.

Old-style neon liquor store sign, west side of 31st Street. By and large, liquor store signs have kept old-style signs, neon and non-neon, that any other type.

There are detective stories in most building names. The Kindred Building on 31st Street is likely named for U.S. Rep. John J. Kindred (1864-1937), a Virginia native who moved to Queens and was elected to the House of representatives, serving from 1911-13 and 1921-29.

For a few decades in the 20th Century 26th Street was named for Kindred, as this 1946 Hagstrom indicates. It had previously been called Merchant Street. Neighboring Crescent Street, because it bends somewhat in its journey through Astoria, has never been given a number.

Vallone and Vallone is a general practice law firm founded in 1932 by the Honorable Judge Charles J. Vallone (narby PS 85 is named for him). Son Peter F. Vallone served as Speaker of the NYC Council, and Peter F. Vallone Jr. is a current [2011] City Councilman from Astoria.

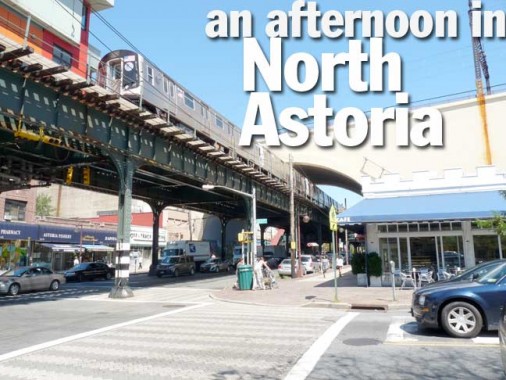

Ditmars Boulevard and 31st Street, the heart of North Astoria, or Ditmars. There are a variety of streets in NYC named Ditmars or Ditmas, the name of a family of colonial-era Dutch settlers. The descendant of one of those families, Abram Ditmars, was the first mayor of Long Island City in 1870. The earliest Ditmars ancestor was Jan Jansen Ditmarsen (John the Son of John from Ditmars) who immigrated to America from Holstein in Germany. The first Ditmars settled in Dutch Kills about 1647.

North of Ditmars Boulevard, 31st Street, freed from the el, becomes residential once more. This is a massive apartment complex that was nonetheless built along esthetic principles.

20th Road snakes in an east-west undulating route between 31st and 46th Streets, just south of 20th Avenue. It’s older than the street grid and was once known as Bowery Bay Road (and since there was another road called Bowery Bay Road that ran from Dutch Kills northeast to the East River that still exists in pieces, it was sometimes called Old Bowery Bay Road.)

Bowery Bay itself is a cove, or an indentation of the East River, just west of La Gaurdia Airport. The bridge to Rikers Island spans it, and it borders a wastewater treatment plant.

“Bowerij” were Dutch farms (NYC’s Bowery is named for them) and the bay may have been named for the colonial-era farm of Abraham Rycken, for whom Riker’s Island is named. Rycken’s farmhouse still stands, and it is the oldest privately-owned home in NYC.

20th Road at 35th Street

20th Road at 42nd Street. The peaked house in the distance was likely more impressive before it was shrouded in siding.

Lawrence Cemetery

Lawrence Cemetery, 20th Road and 35th Street, is one of two private Lawrence cemeteries owned by the family in Queens; the other is in Bayside, several miles east. This cemetery was established in 1703 when Major Thomas Lawrence was interred here. The family figures prominently in city and USA history, with governemnt and military notables; a NYC mayor is buried in the Bayside cemetery.

For 55 years [as of 2011], the Astoria Lawrence Cemetery has been maintained by a neighbor, James Sheehan, who inherited the property and the cemetery from his father-in-law.

Steinway Factory

In an era in which manufacturing is swiftly departing the NYC and American scene, it’s heartening to know that what many consider the finest pianos in the world are built in Queens. Henry Steinway (1797-1871), a German piano manufacturer, immigrated to New York City from Seesen, Germany, in 1853. Between 1870 and 1873, he purchased 400 acres of land in northern Astoria and built the spacious Steinway piano factory on what is now 19th Avenue from 37th-38th Streets.

….Henry and his sons, C. F. Theodore, Charles, Henry Jr., William, and Albert, developed the modern piano. Almost half of the company’s 127 patented inventions were developed during this period. Many of these late nineteenth-century inventions were based on emerging scientific research, including the acoustical theories of the renowned physicist Hermann von Helmholtz. Steinway’s revolutionary designs and superior workmanship began receiving national recognition almost immediately. Starting in 1855, Steinway pianos received gold medals at several U.S. and European exhibitions. The company gained international recognition in 1867 at the Paris Exhibition when it was awarded the prestigious “Grand Gold Medal of Honor” for excellence in manufacturing and engineering. It was the first time an American company had received this award. Steinway pianos quickly became the piano of choice for many members of royalty and won the respect and admiration of the world’s great pianists. Steinway Piano

It was Henry’s son William Steinway who became a renaissance man in Queens when he took over operations of the company upon his father’s death. He completed Steinway Village, which housed workers at the factory.

He was also a transit magnate in the early days of trolley car operations. In 1894, as President of the Steinway Railway Company, he electrified his Long Island City railway that terminated at Northern Boulevard and Woodside Avenue, in a station that still stands. The line was soon extended to Corona.

In the mid-1890s, Steinway began a trolley expansion that would bring his lines into midtown Manhattan. Unfortunately, Steinway passed away before the tunnels could be completed. Later, IRT pioneer August Belmont completed the tunnels, which even today are called the Steinway Tunnels. Excavated detritus from the tunnel was formed into a 100′ x 200′ island in the middle of the East River, first called Belmont Island, but later renamed U Thant Island.

A wealthy and financially adventurous man, he was involved in a number of other business ventures, especially in horse-car railroads in Astoria, New York, where in the early 1870s Steinway & Sons built another factory in the company town of Steinway across the East River from Manhattan. He and principal partner brewer George Ehret built the North Beach Amusement Park (originally called Bowery Bay Beach) which had the benefit of providing recreation and entertainment to Steinway & Sons’ piano-making workforce living nearby in Steinway Village. It also created a demand for Steinway’s network of streetcars, trolleys, and ferries that provided access to the park on land that is now LaGuardia Airport. William also assisted a number of entrepreneurs who established businesses and manufacturing plants on the Steinway holdings. He purchased a distributor of natural gas in the Astoria area, and was a principal figure in several banks throughout the region, especially the Queens County Bank, the Bank of the Metropolis, and the German Savings Bank. In the last decade of his life he became interested in the work of Gustave Daimler, and helped to capitalize the company which much later became Daimler-Benz. American History

1/8/12

Continued tomorrow on Part 2