I’m in Red Hook about once every 4 years or so. When I lived in Bay Ridge I would sometimes bicycle in, but not that often, because it was ringed by a nearly impenetrable barrier of slums, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel entrance. Red Hook, known as South Brooklyn when, in the 1800s, it was indeed Brooklyn’s southern redoubt, has always been an animal all its own. It was easily demarcated by Hamilton Avenue from the regions to its north, now known as Carroll Gardens and Cobble Hill (but not until real estate men and developers of the mid-20th Century bestowed those names — it was all “South Brooklyn” till the mid-20th Century) and then by the BQE.

Red Hook was considered dangerous ground for lone intruders from Bay Ridge until the very early 2000s. For decades, it was a land occupied by gangsters and ruffians, but also by the only honest denizens who could compete with them and survive under their reign: the union workers and longshoremen who busied themselves in the great ports and docks that ringed the waterfront along the Erie Basin and Buttermilk Channel (so named because the channel was so choppy that a churner was unnecessary to render milk carried in vessels that used the strait between Red Hook and Governors Island).

There was also the Red Hook Houses to contend with. The yuppie gentrifiers of Brooklyn have found that the only thing keeping neighborhoods from completely going ‘one-percent’ is the presence of low-income housing in otherwise completely converted regions such as Cobble Hill, Fort Greene, and Williamsburg. In the 1970s and 1980s there were no gentrifiers to speak of in Red Hook, and your webmaster pedaled gingerly to the waterfront and back, noting the shabby, yet genteel housing and Belgian-blocked Coffey and Van Dyke Streets.

The gentrifiers, I’m now confident, will never completely convert Red Hook. There are, of course the trappings of gentrification along Van Brunt, such as the knickknack, ice cream and clothing stores along that row. However, the neighborhood has become more of a place for the yuppies to get their Fairway groceries, their (to me at least, unbuildable) IKEA furniture, and lunch from the Latin summer food stands set up along Red Hook Park soccer fields, and then skee-daddle back to Cobble Hill or Park Slope, leaving the Hook to the ethnics who’ve been there for the last couple of decades. They may have been mostly pushed out of Smith Street, but not Van Brunt and Richards.

What have been pushed out of Red Hook are several of the highlights that appeared in the Red Hook section of the ForgottenBook in 2006, such as the Revere Sugar refinery, the St. John’s Lightship (that had always been partially sunk, anyway) and the Todd Shipyards and its massive dry dock. These have been mostly replaced, or caused to be carted away, by the aforementioned Fairway and IKEA stores. However, as we’ll see, the wheels of change move slowly — for example, the trolley car collection assembled by Bob Diamond and intended to be used in a museum or put to use as a rail link to downtown Brooklyn lie rotting in the sun, as they have been for years.

Court and Nelson streets, strictly speaking, is in Carroll Gardens, not Red Hook, but prior to the coming of the BQE the two neighborhoods (anyone who uses the word ‘nabes’ should be locked in a room with rabid opossums) had more cross-pollination. PJ Hanley’s Bar has roots in the former Norwegian domination of this pocket, as a tavern has been here since 1874. It was purchased by an Irishman, Jack Ryan, in 1898 and there he remained for 60 years, operating as a speakeasy during the prohibition years. The place has been in the Hanley family since 1956.

In 2012, PJ Hanley’s website is still charmingly ‘under construction.’

Harold L. Ickes Playground, Hamilton Avenue between Van Brunt and Woodhull Streets. While the name Harold Ickes is known for Harold McEwen Ickes’ variety of roles in the Clinton administration including Deputy Chief of Staff, this park is named for his father, Harold LeClair Ickes (1874-1952) who was Secretary of the Interior for FDR beginning in 1932.

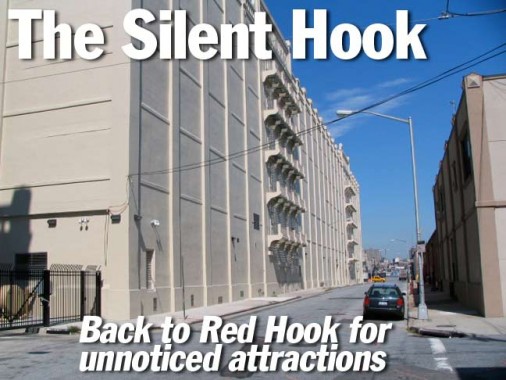

New York Dock Company

Together, these two buildings at 62 and 160 Imlay Street form a sort of huge backdrop along Red Hook’s western front. The New York Dock Company built two massive buildings here that served as railroad sheds, warehouses and loft space in 1912, give or take a year. 62 has been given a new cream paint job and serves as storage space for auction house Christie’s, with millions of dollars of artwork stored within. 160 has been allowed to decay and fall apart, waiting for reuse.

Abandoned NYC took a look inside.

Trainweb will keep you enchanted for hours with details about the New York Dock Company, which was in business from 1901-1983, including numerous photos of Brooklyn’s now nearly deceased freight rail.

All quiet along the Imlay front. You can see the contrast here between the renovated Dock building and the un-renovated one.

Verona Street looking east from Imlay. The street is still Belgian-blocked and the railroad tracks that served the Dock buildings are still in place. More about that ‘big R’ later.

Continuing along Visitation Place we find at #88 the Red Hook Community Justice Center in the school formerly associated with the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church around the corner. One Catholic school has been forced to close after the other as they lose funding — a shame, since Catholic schools have been shown to offer superior educations to the public schools by some reckonings.

Launched in June 2000, the Red Hook Community Justice Center is the nation’s first multi-jurisdictional community court. Operating out of a refurbished Catholic school in the heart of a geographically and socially isolated neighborhood in southwest Brooklyn, the Justice Center seeks to solve neighborhood problems using a coordinated response. At Red Hook, a single judge hears neighborhood cases from three police precincts (covering approximately 200,000 people) that under ordinary circumstances would go to three different courts—Civil, Family, and Criminal…

The Red Hook story extends far beyond what happens in the courtroom. The courthouse is the hub for an array of unconventional programs that contribute to reducing fear and improving public trust in government. These include mediation, community service and a youth court where teenagers are trained to resolve actual cases involving their peers. The Center also has a housing resource center, which provides support and information to residents with cases in housing court, and an AmeriCorps program, the New York Juvenile Justice Corps. Court Innovation

Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church

On Richards Street between Verona St. and Visitation Place, in dark Manhattan schist.

The Roman Catholic Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary was established in 1854 to serve the Irish and Italian dock and factory workers in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn. The first church, located on Ewen [now Verona] and Van Brunt Streets, was dedicated by Bishop Loughlin on October 29, 1855.

A second church, built of gray stone and measuring 175 feet long by 60 feet wide, was erected in 1878, but was destroyed by fire on July 12, 1896.

The present Gothic church was built in 1896 on Richards Street between Verona Street and Visitation [Place], and is across the street from Red Hook Park. A two-alarm fire damaged the interior of the church on December 30, 1949 when a 9-year-old boy accidentally dropped a hot taper into the creche in front of the altar. NYC AGO

For those unaware of Catholic tradition, The Visitation is the visit of Mary (the mother of Jesus) with her cousin Elizabeth (the mother of John the Baptist) while both were pregnant, as recorded in the Gospel of Luke, 1:39–56.

In 1909, Tremont Street was changed to Visitation Place in honor of the church. Red Hook has had more street name shifts than most neighborhoods; along the way, Luque(e)r has changed to Commerce, Leonard to Lorraine, Grinnell to Creamer, Ewen to Verona, Church to West 9th, Partition to Coffey, Elizabeth to Beard and Osage to Reed.

I’ve told the story of the mysterious “R” on the billboard atop this 7-story building at Richards and Verona before, in 2011, but here it is again…

When former owner John Turano bought the building in 1978, the previous business to occupy the site was paper-goods manufacturer E.J. Trum, and Trum’s gigantic sign occupied the frame. When Turano attempted to pull down the letters to install his own sign, the “R” wouldn’t budge, and the lone “R”, and the period that went after the E, have been a part of Red Hook’s landscape for 22 years.

The building is still marvelously intact and looks pretty much the same as it did when it was a factory, even though it’s now residential.

I have a feeling, though, that the sign is of recent vintage (it was there in 1999 but how old was it then?), lettered there by people who know about the building’s history.

Heading south on Richards Street I spotted this mansard-roofed specimen at Pioneer. French Second Empire building styles, marked by slanted roofs like this, were popular in the 1860s, so the building could be that old. Richards Street is named for Colonel Daniel Richards, a leading port developer in mid-19th Century South Brooklyn.

Unusually, Red Hook Park comes in two chunks. The smaller one, since renamed Coffey Park, is between Dwight, Richards, Verona and Pioneer, while the southern one, much larger, is the home of the soccer fields that attract spectators from all over town, and the food carts that do likewise. That Red Hook Park is also home to the Red Hook public pool, is generally between Lorraine, Halleck, Clinton and Columbia Streets.

In 2009 most of NYC’s lamppost luminaires were replaced with new versions of the General Electric M400. I found this 1960s GE M400 at the Pioneer street park entrance. It has a plastic diffuser bowl; most are glass.

Other than the Red Hook Houses themselves, there isn’t much in the way of apartment buildings in Red Hook, so this 6 story what I imagine is a walkup is a standout here at Richards and Sullivan.

For obvious reasons, this sign on Coffey Street, outside the residence of artist Cheryl Stewart, was taken down in May 2011 after bin Laden was shot dead by US Navy Seals. It will be included in the collection of the 9/11 Memorial Museum at Ground Zero.

This unusually-shaped building on Van Dyke street near Richards was built as the Brooklyn Clay Retort and Fire Brick Works.

From the ForgottenBook:

This long, low building … has a distinctive exterior, consisting of 20” thick stones, reminiscent of some churches. It originally was the storehouse of the Joseph K. Brick Company, founded in 1854 to produce items used in gaslighting. Brick originated the fire clay retort, a device used to produce gas used for illumination; gaslighting began to be widely used in the USA around 1850.

Clay retorts were instrumental in the production of gas from coal. The heated retort freed the volatile or gaseous matter contained in the coal. These gases were then carried through a series of pipes and appliances which condensed, washed, and scrubbed the crude gas, and by mechanical and chemical means removed the impurities from the product and made it ready for commercial use. These works may be the very first in the USA to produce fire bricks and clay retorts.

The storehouse was restored in 1995 and 1996 and was the first landmark building designated in Red Hook.

You may remember Rocky Sullivan’s, a microbrewery at Dwight and Van Dyke Streets, as the Liberty Heights Tap Room. Sullivan’s took over the space in 2007.

This historic warehouse built by William Beard in the 1860s has become a mini-artists’ colony with a number of galleries run under the umbrella of the Brooklyn Waterfront Artists’ Coalition. Each May, the pier is the site of the Waterfront Arts Festival. It is also slated to become home to Fairway Market, a project not without controversy as its detractors say it would bring unwelcome auto traffic to the quiet neighborhood.

The building is divided into sections by 12-16″ thick brick walls. The building itself is supported by massive square yellow pine posts supporting heavy girders. Its interior is fascinating not only for the art shows, but as a representation of unaltered Civil-War era construction.

Like its partner the Beard Street Pier, the warehouse dates to the Civil War era and stored grain, coffee, mahogany, nuts and tea. On the top floor, donkeys pulled a pulley system used to hoist 100-lb. coffee bags in the pre-elevator era.

The warehouse is accessed by a walkway on Beard Street south of Van Brunt.

While the Beard Street Warehouses, another vast warehouse built by Beard have become the Fairway Supermarket, the collection of trolley cars assembled by Bob Diamond and the Brooklyn Historic Railway Association, in hopes of running a trolley line along the Brooklyn waterfront possibly as far as Old Fulton Street at the old Fulton Ferry site still is parked outside, in about as an illogical site for storage as can be conceived. The cars are open to the full ravages of salt water, winter storms, and assault by vandals.

The project has been the victim of capriciousness from local politicians, who first support the project, then undermine it.

Sunny Balzano’s decades-old institution on Conover between Reed and Beard Streets has been in place here for over a century.

Ask a car service to take you to “the bar” in Red Hook, and you’ll wind up at an unassuming little place by the river, near some railroad tracks that go nowhere. The beatific, Beatniky owner, Sunny, greets you warmly from beneath a mop of gray hair and a portrait of his great-grandfather, who opened the bar in 1890. Since then, the place has gone through various incarnations, as a restaurant and a longshoremen’s hangout, but now, says Sunny, “it’s just a meeting place for folks—painters, writers, musicians, plumbers—who care about each other so much they don’t mind the trip.” NY Magazine

On one of my Forgotten NY tours, held a few times each year, Forgotten Fan Mike Olshan introduced us to Sunny Balzano, whose family’s bar on Conover between Beard and Reed Streets has been a Red Hook waterfront institution for three generations. Sunny treated us all to a brew as we bellied up to a bar that faced several pieces of his own artwork. His family has owned the business for decades, with his uncle John keeping the bar open every day until 6PM, serving sandwiches and Italian food to longshoremen and dock workers. Gradually, the Red Hook docks became silent as the shipping industry moved across the harbor to New Jersey, depriving the old place of many of its old customers, but Sunny and John discovered that a new clientele of artists and musicians from nearby Williamsburg was coming to the bar. After John passed away in 1994, Sunny ran it as a nonprofit club featuring musicians and local performers, opening Friday nights only, and after acquiring a new liquor license and renovating the bar, Sunny was able to open a couple other nights a week as well. The bar is now a neighborhood gathering place for its new breed of customers, many of whom don’t know it’s a family institution. Sunny opens Wednesday, Friday and Saturday evenings. If there’s a gentle man with long, flowing gray hair behind the bar, ask Sunny about the old place…he’ll regale you with tales of old Red Hook.

Scene from Van Dyke Street and its ancient architecture and Belgian blocked street. Some things in Red Hook never change…

…but as this mess on Conover proves, change is ever ready to come if it is permitted to.

Pier 41

Pier 41, also known as the Merchant Stores, was developed by Col. Daniel Richards as a shipping and warehousing center in the late 1870s. For many years it was home to Morgan Soda, which distributed the White Rock brand. Presently Pier 41 is home to Flickinger Glassworks (a glassblowing company), other small industries, and the famed Steve’s Authentic Key Lime Pies.

A selection of newer versions of ornate wall lamps, complete with radial-wave reflectors, has been installed along the walkway, and a sign that resembles the Department of Transportation’s green and white signs identifies a “Barnell Street” but no such street is on the map.

Erie Basin: A store selling antique jewelry on Van Brunt and Dikeman Streets has taken the name of the massive harbor and storage depot, considered the southern terminus of the Erie Canal, developed by William Beard.

Fort Defiance, a cafe/bar across the street from Erie Basin, also commemorates a piece of Red Hook history:

General Israel Putnam came to New York on April 4, 1776 to assess the state of its defenses and strengthen them. Among the works initiated were forts on Governor’s Island and Red Hook, facing the bay. On April 10, one thousand Continentals took possession of both points and began constructing Fort Defiance which mounted one three pounder cannon and four eighteen pounders. The cannons were to be fired over the tops of the fort’s walls. During May, Washington described it as “small but exceedingly strong”. On July 5, General Nathanael Greene called it “a post of vast importance”, and three days later, Col. Varnum’s regiment joined its garrison.

The Sproule map shows that Fort Defiance complex actually consisted of three redoubts on a small island connected by trenches, with an earthwork on the island’s south side to defend against a landing. The entire earthwork was about sixteen hundred feet long and covered the entire island. The three redoubts covered an area about four hundred by eight hundred feet. The two principal earthworks were about one hundred fifty by one hundred seventy-five feet, and the tertiary one was about seventy-five by one hundred. On July 12, the British frigates Rose and Phoenix and the schooner Tyrol ran the gauntlet past Defiance and the stronger Governor’s Island works without firing a shot, and got all the way to Tappan Zee, the widest part of the Hudson River. They stayed there for over a month, beating off harassing attacks, and finally returned to Staten Island on August 18. It would appear that gunfire from Fort Defiance did damage to the British ships. wikipedia

One of Van Brunt Street’s charming storefronts, complete with sleeping cat.

I have a hard time resisting taking pictures of this ancient Van Brunt storefront, whose odd collection of artifacts has a thicker layer of dust each time.

Yet another cleverly named establishment, the liquor store Dry Dock honors one of Red Hook’s former landmarks.

The Todd Shipyards, also known as New York Shipyards, fronted along Beard and Halleck Streets west of Columbia and once sported the largest dry dock on the east coast. The Monitor, the first ironclad vessel from the Civil war era, was once repaired there. The yards featured brick structures with heavy timber posts and machine that had 1920s-era Bauhaus industrial design highlights with skylights and 20-foot-tall windows.

Philip Lopate in his book “Waterfront” describes an incident in which the crew of a damaged Central American freighter were detained here for 6 months until its owner could pay for repairs. Its crew was too afraid to venture into the Red Hook streets for provisions.

Of course, Todd Shipyards, and its dry dock, were uprooted a few years ago to make way for an IKEA furniture store, parking lot, and Erie Basin-facing waterside park.

A peek down a Red Hook side street at another clay retort and its now-inactive smokestack.

One of Red Hook’s charming aspects is that some of its businesses put up colorful directional signs directing shoppers to their locations, in these cases, Pier 41.

The Kentler International Drawing Space takes its name from the name on the building pediment, which in turn honors German immigrant haberdasher William Kentler, who established his business in 1854 and built this building on Van Brunt in 1877.

The Hope & Anchor was established on Van Brunt and Wolcott in the mid-2000s. I’d like to think it was named for the Hope & Anchor in London, an early punk/new wave bastion…

Red Hook Memorial Doughboy: This memorial, which honors those local heroes from Red Hook who died while serving their country in World War I, was dedicated in 1921. Augustus Lukeman (1872–1935) was the sculptor commissioned by a war memorial committee, which solicited voluntary contributions totaling $10,000 from the citizens of the Third Assembly District for the sculpture. Arthur D. Pickering was the architect who designed the granite pedestal. NYC Parks

This liquor store on Van Brunt and Sullivan has a more old school vibe than the Dry Dock seen earlier.

A pair of low-rises on King Street. This is typical of the humble private houses found on Red Hook side streets.

Red Hook Bait and Tackle Shop (Pioneer and Van Brunt) was indeed a bait and tackle shop before its owners took over in 2004 and opened a bar/music venue. Its website has a capsule history of Red Hook.

Kevin’s is “an adorable eatery noted for its seafood specialities” operated by chef Kevin Moore.

The Transoms of Red Hook (FNY 2004)

Red Hook Trolley Revival (FNY 2000)

6/18/12