I was circumnavigating Gramercy Park (a small parcel of a private park between East 20th and 21st Streets and 3rd Avenue and Park Avenue South), preparing for a possible tour or new ForgottenBook Again entry. Mere commoners are not permitted into Gramercy Park. You must be a keyholder at any of the buildings surrounding the park to enter it (and some selected buildings in the area, as we will see). On this early summer day, though, the foliage combined with scaffolding so completely obscured Gramercy’s buildings that I beat a retreat after a cursory walk and headed south on Irving Place.

Irving Place, like nearby Madison Avenue, is named for a historical figure. Unlike Madison, though, the person Irving Place is named for was still among the living at the time, and was at the height of his literary career. Washington Irving (1783-1859), who met his namesake George Washington while a young boy, was popular both in the States and in Europe for his essays and fiction, and was the creator of Ichabod Crane, Rip van Winkle, and the tricornered Father Knickerbocker, NYC’s mascot.

Union Square, Irving Place and Gramercy Park, as well as Lexington Avenue, the northern extension of Irving Place north of the park, were laid out and begun by developer Samuel Bulkley Ruggles beginning in 1831. They all were originally part of his property.

GRAMERCY PARK.

[Ruggles] purchased the Gramercy land from former NYC mayor James Duane. Ruggles drained the swampy land, and from the British Trinity’s St. Johns Park, he borrowed the idea of a private park. He gave the new lot owners a key to their own private tax-exempt park or ‘pleasure ground,’ as parks were then called. This enhanced the value of the surrounding land. (Housing was not built around the park until the 1840s.) Ruggles went on to develop Union Square. In 1838, he served one term in the state legislature. He was sponsored for the Canal Board by his friend Governor William H. Seward, and served on it for 18 years. He supported work on the Croton Aqueduct system.

With Edward Curtis, he constructed warehouses on the Atlantic Docks in Brooklyn. This 1851 project was a financial failure, and it ended Ruggles’ real estate career. He was a trustee of Columbia College from 1836 to 1881. As a businessman, he was a director and comptroller of the New York & Erie Railway Company. He was part of the board of directors of the Panama Railway Company in 1849.

In 1862, he was appointed commissioner for the Union Pacific Railroad. Ruggles was a delegate of the United States to the International Monetary Conference at the Paris Exposition of 1866. In 1869, he represented the United States as delegate to the International Statistical Conference at The Hague. Ruggles served as the trustee of the Astor Library. He was the author of numerous reports on transportation, commerce and monetary policy, including ‘Report upon the Finances and Internal Improvements of the State of New York’ (1838) and ‘International Coinage’ (1867). He visited his lifelong friend and associate Peter Cooper regularly until his death. He is buried in Trinity Cemetery. Museum Planet

STUYVESANT FISH HOUSE, Irving Place and Gramercy Park South. This is the second “Stuyvesant Fish” house in the general area: there’s another one on Stuyvesant Street, a few blocks away. The one on Stuyvesant Street was lived in by Nicholas Fish, married to Elizabeth Stuyvesant, hence the hyphen. This one was lived in by family scion Stuyvesant Fish, hence no hyphen. It was built in 1845 and lived in by Fish until 1900, and it was later occupied by famed publicist Benjamin Sonnenberg beginning in 1931.

I’ve always loved the corner apartment building at 81 Irving Place and 123 East 19th — it’s festooned with dozens of terra cotta gnomes. And more gnomes.

For this 14-story apartment house, architect George Pelham, one of New York’s most active apartment-house designers, exploited the requirements of the zoning law to create an exuberant design [in 1929-1930] with dramatic setbacks and a striking rooftop pavilion surrounding the water tower. The building, planned with 107 small apartments, is faced with brick, often laid in intricate patterns to add excitement to the facades. The building is ornamented wth beige terra-cotta detail of a very high quality. Terra-cotta features include columns, balconies, and gargoyles embellished with animal heads, monsters, and other fanciful detail. NYC Architecture

The big-eared one seems to be influenced by cartoonist R.F. Outcault’s 1890s creation, The Yellow Kid.

THE GRAMERCY, Irving Place and East 18th Street. Most of Irving Place’s buildings were originally two to four-story walkup buildings but interspersed are apartment buildinsg, such as this one built in 1899. It has since been converted to luxury apartments.

The building on the left is a new building built in 2009. According to Jim Naureckas’ Songlines, residents of this building have keys to Gramercy Park, which sort of contradicts its exclusivity.

“TWIN CROOK.” As far as I know, this is the only Twin Bishop Crook in NYC, at the SE corner of Irving Place and West 18th Street. In the early 20th Century cast iron era, there was a specialized Twin post made to illuminate two sides of a street at once, and Bishop Crooks were never twinned. After the classic lamps’ comeback in the 1980s, Twin versions of the long-armed Corvington posts became commonplace, and there were even new Twins produced (mainly along West 40th and 42nd streets and 6th Avenue around Bryant Park) and along Central Park West. But this is the only Twin Bishop Crook.

Note also that the sidewalk side of the diffuser bowls are blacked out so harsh light doesn’t enter the buildings facing the lamps, and the two different Bell luminaire styles. On the left is the Bell introduced in the 1980s when castirons made their comeback, while the one on the right matches the older Bell styling of the 1940s.

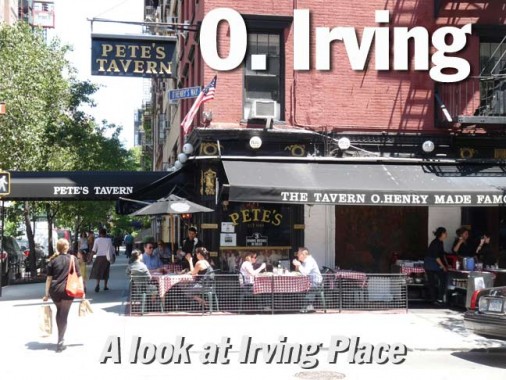

PETE’S TAVERN, Irving Place and West 18th, NE corner. There are a number of taverns in NYC jostling and vying for the title of the city’s oldest bar. McSorley’s, on East 7th and Cooper Square, claims the title. But there’s also the Bridge Cafe in the Seaport neighborhood. Pete’s Tavern has also joined the battle. It’s all a matter of semantics, as Pete’s is billed as ‘New York’s Oldest Original Bar.’

The building it occupies was built in 1829 and featured a grocery (in previous centuries liquor was sold and consumed in groceries) by 1851, with a more specific saloon called Healy’s in place by 1864. It was operated as a flower shop hiding a speakeasy during Prohibition days, after which Peter “Pete” Belles purchased it, giving the place the famed name. Since the 1950s, an Italian menu has been featured, though traditional bar food like burgers and steaks are sold too.

Before and after Prohibition Pete’s was frequented by literary types such as William Sydney “O. Henry” Porter (as in the old Lion’s Head and White Horse Taverns in Greenwich Village).

The 1910 12-story high-rise across the street from Pete’s illustrates the changes that have come to Irving Place over the years. The space was occupied in the 19th Century by the smaller buildings you see to its left and right.

Besides mixed-use buildings, Irving Place also features purely residential buildings such as this group of stooped buildings constructed in the mid-1840s.

I’m featuring the building at East 17th housing the Casa Mono, or Monkey House, Restaurant becuase it has a hidden Forgotten NY element.

Above the door, notice the metal letters spelling out the address.

IRVING HOUSE, SW corner Irving Place and West 17th. Despite a local legend, there is no evidence that Washington Irving lived here at 122 Irving — although Edgar Irving (reputed by some as his nephew), lived at #120, next door — and had a son who he named Washington. The building was constructed in 1844.

Beginning in 1892, the building was occupied by actress Elsie DeWolfe, who became a prominent interior decorator, and her partner, literary agent Elisabeth Marbury, who jokingly called themselves “The Bachelors.” The story of the Algonquin Round Table, with its collection of writers, actors and wits, is often told — but no so much The Irving House, where The Bachelors invited George Bernard Shaw, Sarah Bernhardt, and Oscar Wilde in for tea, among other luminaries of the times. It’s possible that DeWolfe began the rumor that Irving had lived here.

One of the handsomest historic plaques in town can be found mounted on the building — it even has its own lamp for nighttime illumination. It features Irving in profile, his birth in New Amsterdam, the future NYC in 1783, his death in Tarrytown in 1859, a scene from his collection Bracebridge Hall and depictions of Rip van Winkle and Ichabod Crane.

Its assertion that “This house was once the home of Washington Irving” is all wet, though. At the bottom are the inscriptions “New York, 1934” and “Fecit A. Finta,” indicating the work of Hungarian sculptor Alexander Finta (1881-1958)

WASHINGTON IRVING HIGH SCHOOL, across from the Irving House, was constructed from 1911-1913 as Girls’ Technical High School with C.B.J. Snyder, the premier architect of NYC shools, its primary designer. The insides are like a museum, preserving a generous sampling of furnishings and art.

From my Open House 2005 page, which depicts the interior:

[The interior] features beautiful oak panelling in the lobby and a series of murals, one 1915 series in the lobby by Barry Faulkner, a gift to the city by the Municipal Arts Society depicting scenes from early Manhattan; another from the same year on the back wall of the auditorium by illustrator Robert Knight Ryland depicting Dutch and Indians trading; a 1932 series in the front of the auditorium of female figures resembling the Greek Muses by J. Mortimer Lichtenauer; and a 1932 series on the staircases depicting old and new Manhattan by Salvatore Lascari.

Friedrich Beer sculpted this bust of Irving, which was originally installed in Bryant Park in 1885 and moved here to Irving High in 1935.

8/17/12