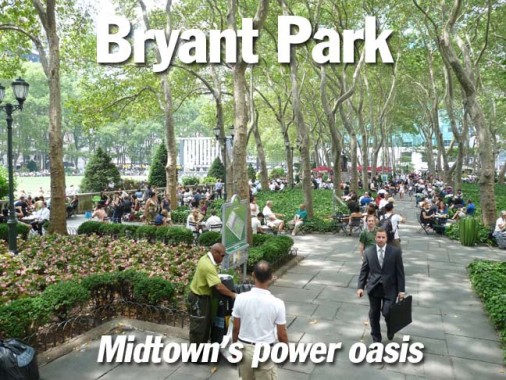

I do not remember Bryant Park during its legendary Bad Old Days of the 1970s and 1980s, when, according to all the chroniclings I have read, it was a ‘wretched hive of scum and villainy’, second only to the historic Five Points in its concentration of assorted miscreants: drug dealers, hookers, muggers, killers, bums (and some fit more than one category). During the Depression, an iron gate and a high hedge had been added to the park exterior, thereby insulating the interior from the surrounding Midtown neighborhood. For those who believe Manhattan was only cleaned up after Rudy Giuliani was elected mayor, Bryant Park began its turnaround in 1980 when the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation was inaugurated. The park was closed between 1988-1992 and acquired its present layout that year, that expanded its large center lawn and outside and inside walkways. The tables and folded chairs, which pretty much depend on the honor system to stay in the park (though the park is adequately patrolled) were also introduced during that time. The park’s Upper Terrace, which had been its most active drug market, was leased to the trendy Bryant Park Grill, which became an instant hot spot.

In the 1970s and 80s I did not get into Midtown that much. Since I am largely a yellow-bellied coward, I avoided Bryant Park because of its rep, and whenever I needed to catch a bus at the Port Authority, I’d take the R train to Times Square and use the underground passageway to 8th Avenue rather than dare the Deuce (this was also year before I started toting a camera everywhere, anyway).

As a matter of fact I did not see much of Bryant Park at all, though I’d been apprised of its improvements, until 2000 when I scored a job at the World’s Biggest Store and began using my lunch hours to wander about Forgottening. One April afternoon, I meandered into the park and there, performing on the stage before the big lawn, was Carly Simon. I was not the biggest devotee of her brand of soft pop, but marveled on how fun it was to be back working in Manhattan after several years working in Port Washington in Long Island. You wander into a park, and there’s world-class entertainment. Unfortunately it was one of the high points of my Macy’s stint, but that is a story for my memoirs if I ever attain true fame.

In July 2012, once again stumbling around Midtown, I again entered Bryant Park amid wondering when my latest job-free stint would be relieved, and in giving the park another look, found several items that have survived its evolution from the Gilded Age through the Bad Old Days and its emergence again into a new Gilded Age.

Just about all my entrances into Manhattan are via the Long Island rail Road tunnels into Penn Station, and I thence started walking north on 7th Avenue toward the park in a general direction. I must have passed this building thousands of times during my 4-year Macy’s stint but hadn’t before taken notice of its terra cotta exterior and, to be honest, its utter strangeness. There is a great show made of heraldic stylings, with two shields proclaiming it part of the Lerner Shops chain of women’s fashions.

Ephemeral New York claims:

In 1907, this once-huge mass market fashion chain—does the label even exist anymore?—opened on Seventh Avenue in the 30s as a plus-size retailer.

Further research, though, indicates that Lerner’s was founded no earlier than 1918 by Samuel A. Lerner (uncle of lyricist Alan Jay Lerner, of showbiz team of Lerner and Loewe) and Harold M Lane, and it became New York and Company around 2002. So, this may well be Lerner Shops’ flagship, but went up in 1918 and not earlier.

But a closer look at the place is rather bizarre. There are those four heads on the roof, the second of which is grinning maniacally, and there’s that male mannequin in the red dress on the second floor.

Freight entrance, 135 West 36th. Some more terra-cotta beauty, with a pair of peacocks. The building probably goes back to the late 1920s when buildings still added some rococo to even the side doors used by swarthy deliverymen, unshaven, with unflicked cigarette butts in their mouths, flaking ashes, bore elements of classic styling. The carven letters identifying the door are executed with precision and resemble the Goudy typefont.

Broadway, which is no longer broad, and West 36th. Broadway bears 2 lanes for traffic, a lane for parking, a lane with planters for idlers in the midday sun, and a green lane for bicyclists.

Friends Electric

At the corner of West 40th Street and 6th Avenue, the southwest corner of Bryant Park, after an absence of a few years, once again remembers the legacy of one of history’s great inventors.

Tesla gained great fame but his last years were not happy ones. He had never married, not paid much attention to his finances and died destitute at the New Yorker Hotel at 8th Avenue and 34th Street, where a memorial plaque was dedicated to him a few years ago. He loved feeding the pigeons in Bryant Park.

above from Lost New York, Nathan Silver

When you stand in Bryant Park, you stand in a Native American hunting ground in the pre-colonial era; a public space commissioned by NY Governor Thomas Dongan as early as 1686; a potter’s field in which unclaimed corpses were interred (1823-1840), and the “back yard” of the Croton Distributing Reservoir (1847-1890s).

1853 saw the construction of the massive iron and glass Crystal Palace (in response to London’s own Crystal Palace built in 1851), to house the “Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations” opened July 14 of that year with an inagural speech by President Franklin Pierce. 4000 exhibitors displayed the cutting edge industrial, art and consumer goods of the era, and the Crystal Palace developed into NYC’s premier tourist attraction. Despite all that the Palace lost $300,000 its first year. The building’s design was derived from London’s Crystal Palace by architects Georg Carstensen (1812-1857; a Dane, he assisted in the development of Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens, Europe’s first amusement park) and Charles Gildemeister. It’s remembered today as the New York City grand edifice that melted in 15 minutes…after it caught fire October 5, 1858. London’s Crystal Palace survived until 1936 when it too succumbed to a conflagration. However, all was not completely lost. Its intriguing use of iron helped convince a generation of architects, including NYC’s James Bogardus, to use wrought iron in the construction of roofs and building fronts, and the fruits of this inspiration can still be seen in NYC’s own flocks of iron-fronted buildings in Soho and other neighborhoods. The dome of the Enid Haupt Conservatory of the New York Botanical Gardens in the Bronx, as well as several other greenhouse buildings around town, rather resemble the Crystal Palace dome.

Military drills were held in Reservoir Square, as the yard was called, during the Civil War.

A fresh start

In 1884 Reservoir Square was renamed Bryant Park in honor of then-recently deceased poet, editor and civic reformer William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878). Famous since his teenage years for poems like “Thanatopsis” and the Civil War elegy “My Autumn Walk” he was for over 50 years the editor of The New-York Evening Post, which had been founded by Alexander Hamilton in 1801. In those days the Post, in contrast to its tabloid style of today, was an erudite, literary publication rather like today’s weekly The New Yorker.

Herbert Adams’ sculpture memorial appeared in 1911, protected by Thomas Hastings’ pedestal and columned dome. A stack of papers is on his lap, and a blanket draped across his knees makes him look like he is wearing a dressing gown. An inscription of Bryant’s “The Poet” can be found on the pedestal.

The statue is at the east end of Bryant Park, adjoining Bryant Park Grill.

The memorial is flanked by two decorative urns featuring cow skulls.

The New York Public Library, meanwhile, was opened in 1912, replacing the reservoir; some of the reservoir walls can still be found in a basement area of the library, and some of the library stacks lie under the park. The front steps of the library, including the sculpted lions Patience and Fortitude, are officially part of Bryant Park.

Long before its 1988-1992 restoration, Bryant Park had been redesigned in 1899, when the adjoining Croton Receiving Reservoir was demolished. Work later began on the New York Public Library to take its place. Bryant Park acquired terraces, public facilities, and kiosks, as well as these massive bronze lampposts that light the park entrances on West 40th and West 42nd Street and 6th Avenue. They bear acanthus-like carven ornamentation, and a quartet of rams’ heads on the squarish base, with clawed feet on the bottom. They are serious lamps and are no doubt heavy enough to prevent theft.

The lamps at the main entrance on 6th Avenue are a bit different, as they bear 5 luminaire globes, one big and 4 small, instead of the single large globe at the other entrances.

I cannot verify they were installed at the park’s 1899 renovation, and the internet seems to be silent regarding them. If you have any information about heir designer, date of installation, etc. let me know in Comments.

A pair of South American historic personages are remembered on the 6th Avenue side of the park, which is fitting since, as Avenue of the Americas, 6th Avenue honors members of the Organization of American States.

A geologist, poet, statesman and scholar, José Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva (1763-1828)was a leading contributor to the Brazilian Constitution of 1824. Brazil achieved its independence from Portugal–mostly peacefully–in 1822. Andrada became Brazil’s interior as well as foreign minister. He fell out of favor, however, the next year for opposing Brazilian emperor Don Pedro I’s policies and was exiled to France. Brazil’s constitution, featuring many of his ideas, was drawn up the following year.

José Lima’s sculpture of Andrada was presented to the USA as a gift by Brazil in 1954, the same year it took its place on The Avenue of The Americas. It was the winner of an open competition in Brazil.

Formerly at 6th Avenue and 42nd Street, Andrada’s statue, a 1954 work by José Otava Correia Lima, was moved to 6th Avenue and West 40th Street (Nikola Tesla Square) during Bryant Park’s 1990s renovations.

Benito Juárez (1806-1872) was a five-term president of Mexico between 1858-1872, repelling a French invasion and subsequent Habsburg rule that followed Juarez’ stoppage of interest payments on loans to France, England and Spain.

Today Benito Juárez is remembered as being a progressive reformer dedicated to democracy, equal rights for his nation’s indigenous peoples, his antipathy toward organized religion, especially the Catholic Church, and what he regarded as defense of national sovereignty. The period of his leadership is known in Mexican history as La Reforma del Norte (The Reform of the North), and constituted a liberal political and social revolution with major institutional consequences: the expropriation of church lands, the subordination of army to civilian control, liquidation of peasant communal land holdings, the separation of church and state in public affairs, and also the almost-complete disenfranchisement of bishops, priests, nuns and lay brothers. wikipedia

The sculpture, by Moises Cabrera, was dedicated on October 9, 2004, a gift from the Mexican state of Oaxaca, from where Juárez hailed.

Entering the park from 6th Avenue and West 41st Street, you are immediately greeted by a massive glazed granite fountain, which, thanks in part to an extraordinarily rainy April in 2007, was allowed to shoot great torrents the day your webmaster photographed it the next month. The fountain, designed by Charles Adams Platt, was installed and dedicated in 1912 to Josephine Shaw Lowell (1843-1905), a social worker and founder of the Charity Organization Society.

Hail the Black and Gold

AMERICAN RADIATOR BUILDING.

This West 40th Street iconic, neo-Gothic 23-story skyscraper was designed by Raymond Hood and André Fouilhoux for the American Radiator Company, and was later renamed the American Standard Building. It features black brickwork and gold leaf on its terra cotta friezes.

There are overwrought figures on the exterior that appear to depict figures undergoing great suffering, but were apparently meant to allegorically depict the transformation of matter into energy, while the black brick symbolized coal. The lobby also features black marble and mirrors. There was originally a display hall for American Radiator products. In 2001, the building became the Bryant Park Hotel.

Rene Paul Chambellan (1893-1955) was employed by Hood and Howells for the ornamentation and sculptures. Chambellan’s work also appears at other well-known NYC buildings such as the NY Life Insurance Building, the Chanin Building and the old NY Daily News building.

In what must be a hommage to the ARB, fences surrounding Bryant Park, as well as the railings on the subway entrance staircases, are black with gold trim on the fleur-de-lis ornamentation.

2 doors down from the ARB is the Engineers’ Club Building, constructed in 1907, via a donation from steelman/philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, for a social organization for American engineers. This was once the site of the Comstock School for Young Ladies, an organization known as a finishing school.

A couple more lamps, seen from the pedestrian passage that runs from West 40th to 42nd between 5th and 6th Avenues. The one on the left can only be described as a Type A twin, with a Type A park lamp (recognizable by a taller shaft than the more frequent Type B) topped by a double luminaire. The post on the right is featured on this walkway and no other part of Bryant Park.

Since a pedestrian walkway from W. 51st north to W. 57th was recently named 6 1/2 Avenue, I think the city ought to follow the trend and call this stretch 5 1/2 Avenue!

On this day the Bryant Park lawn was jammed as Broadway theatre entertainers worked the stage. Bryant Park’s large central lawn, formal pathways, stone balustrades, and borders of London plane trees are the work of Queens-based architect Lusby Simpson, the winner of a competition for the park’s redesign instituted by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses in the winter of 1934.

The planters along the balustrade that hold lush vegetation in the warm months are likely a product of that 1930s renovation.

New York’s first midtown carousel in the modern era, Le Carrousel of Bryant Park, produced by the Fabricon Carousel Company of Brooklyn, opened March 21, 2003. It features 10 brilliantly painted ponies, a frog, a cat, a deer and a rabbit. It’s $2.00 a ride.

The dour-looking bust of German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe incongruously faces the merry carousel.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was one of Germany’s greatest writers, as well as a playwright, essayist, translator and scientist. He worked on his greatest triumph, Faust, a philosophical work in which a Renaissance scholar enters into a deal with the devil, for over sixty years. Faust was based on a story by British writer Christopher Marlowe (a Shakespeare contemporary) but Goethe’s was a work that far transcended its source material.

The Faust legend is still being remade in countless versions, from Damn Yankees to Bedazzled.

(from the Faust Legends website)

This bust of Goethe was first cast about 1832 by Karl Fischer, and was obtained by the Goethe Club of New York in 1876 and was placed in the Metropolitan Museum. The original iron bust was recast as a bronze replica in 1934 and placed in Bryant Park.

Goethe’s name is often butchered by non-German speakers: it’s approximately, GER-ta.

“Don’t you know who I am?” the Buddha-like statue of Gertrude Stein seems to say, as midtown lunchers ignore her.

Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) was a poet and novelist whose Paris home became a gathering place for the leading artists and writers of her time, including Pablo Picasso, Henry Matisse and Ernest Hemingway in the 1920s and 1930s.

She is probably best known to those unfamiliar with her work for her commentary on Oakland, California: “There is no there there.” Stein was born in Allegheny, PA, but her family lived in Oakland for a time when she was a child. When she returned there many years later, she found that her childhood home had been knocked down…hence her reaction.

Among Stein’s works are Three Lives, Everybody’s Autobiography (which contains the Oakland quote) and The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, which despite its title was pretty much the story of Stein’s life until 1932. Jo Davidson’s sculpture was installed in the park in 1991.

No matter how rich or powerful you might be, 100 years after your death it’s anyone’s guess if anyone will still recognize your name. William Earl Dodge (1805-1883), the “Christian Merchant,” was a dry-goods manufacturer, a leader in copper and metals trade (Phelps Dodge Corporation), a civic leader, vocal opponent of slavery and an organizer of the Young Men’s Christian Association (the YMCA) and the National Temperance Society.

Originally in Herald Square in the triangle formed by Broadway, 6th Avenue and West 35th Street, John Quincy Adams Ward’s 1885 Dodge monument was moved to Bryant Park in 1941 to make way for the James Gordon Bennett Memorial “Bell Ringers Monument,” which itself was being moved from another part of town. At times, NYC can seem like a chessboard.

Bennett was president of the New York Herald.

HSBC Bank now underwrites Bryant Park’s famed book and magazine racks, which, like the tables and chairs is protected by the hnor system and the park’s security guards.

Coliseum Books, which found a home on 11 East 42nd Street after moving out of its longtime location on Broadway and West 57th Street in 2004, maintained a book stand in the park until it went the way of most bookstores in January 2007. Independent bookstores are finding it harder and harder to stay in business in NYC. The original Bryant Park Reading Room originally opened in 1935 and ran till 1944.

Ping pong, or table tennis players have a table on the West 42nd Street side near 6th Avenue.

The game originated as a sport in Britain during the 1880s, where it was played among the upper-class as an after-dinner parlor game. It has been suggested that the game was first developed by British military officers in India or South Africa who brought it back with them. A row of books were stood up along the center of the table as a net, two more books served as rackets and were used to continuously hit a golf-ball from one end of the table to the other. Alternatively table tennis was played with paddles made of cigar box lids and balls made of champagne corks. The popularity of the game led game manufacturers to sell the equipment commercially. Early rackets were often pieces of parchment stretched upon a frame, and the sound generated in play gave the game its first nicknames of “wiff-waff” and “ping-pong”.

A number of sources indicate that the game was first brought to the attention of Hamley’s of Regent Street under the name “Gossima”. The name “ping-pong” was in wide use before British manufacturer J. Jaques & Son Ltd trademarked it in 1901. The name “ping-pong” then came to be used for the game played by the rather expensive Jaques’s equipment, with other manufacturers calling it table tennis. A similar situation arose in the United States, where Jaques sold the rights to the “ping-pong” name to Parker Brothers. wikipedia

A number of movies are shown weekly on Monday nights facing the Bryant Park lawn during the summer months. To me, this selection appears a bit stale — watch Turner Classic Movies for any length of time, and you’ve already seen most of these — but they’re doing something right since the lawn is invariably packed on movie night.

Bryant Park’s restrooms, which probably arrived with its 1899 renovation, feature a cattle skull motif that also turns up on the urns that flank the William Cullen Bryant statue. Other than its likely allusioon to stability and strength, I haven’t been able to find out much about this symbol, which crops up in architecture of the late 1800s to just inside the 20th Century.

5th Avenue station entrance, a direct connection to the #7 Flushing Line, and a passageway also goes to the IND 6th Avenue Line. Those two wrought iron station lamps are unique in the system.

Let me yank something out of my memory hat. I am a rather frequent Boston visitor (though I haven’t gone since 2006) and the wrought iron here reminds me of the much more ornate wrought iron you find at the Copley Green Line entrance you find on Boylston Street. The 5th Avenue entrance is on the side of the New York Public Library — as the Copley station flanks the Boston Public Library.

#11 West 42nd, the 31-story Salmon Tower (York & Sawyer, 1927) houses NYU’s Midtown Center for Continuing Education. Note the months (with corresponding zodiac signs) around the entrance, and the figures above representing the professions. This was the final home of Coliseum Books. Jim Naureckas’ NY Songlines

Most buildings are set back at the top to allow sunlight below. The W.R. Grace Building (1974), at 1114 6th Avenue with a front entrance on 42nd, does the opposite with a swooping form, the widest part of the building at the base. It makes an ultramodern pairing with 1100 6th — but that ultramodern look is only cladding, since it was built in 1912!

You must be a ‘wich. I exited the park at the popular ‘wichcraft kiosks at the NW park entrance. The chain was founded in 2003, with popular TV chef Tom Colicchio a co-founder.

9/9/12