When NYC was still subject to the British Crown there were a number of streets downtown named Queen, Duke, and other royal titles. Pretty much all of them were wiped off the map after the USA won independence for good and all in 1783 and the British evacuated the country and NYC in particular. Queen became Pearl, King George Street became William (for early NYC mayor Wiliam Beckman), Crown became Liberty, and so forth. There are a couple still around, though — Prince Street in SoHo is one, and Nassau Street is another.

Nassau Street was named by 1696 for the House of Orange-Nassau in the Netherlands, which extended back to the Charlemagne (he ruled western Europe from 768-814 AD). King William III of England, the person for whom the street name was bestowed, became king in 1689 and was Dutch by ancestry; his wife, Mary, was British. William’s army had forced Mary’s father, King James II, out of power. Dutch royalty remains to this day in the House of Orange-Nassau.

Nassau was also an old name for Long Island. Dutch explorers originally called it t’Lange Eylandt, or Long Island, but then during William III’s time the British took to calling it Nassau Island. After US independence the name Long Island was restored, but when a new county was formed for three eastern towns of Queens in 1898, it was decided to name the new county Nassau. The capital city of the Bahamas, meanwhile, was named thus in 1695, also for William of Orange.

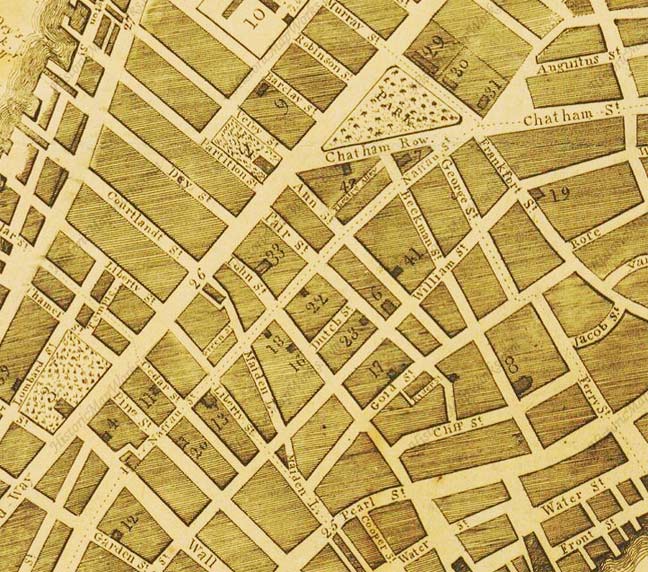

This colonial-era map from the late 1700s shows Nassau Street running north from Wall and Broad Streets to Chatham Row and George Street, today’s Park Row and Spruce Street. The current orthography was still using the “long s” which died out about 1800.

Like Greenwich Street, Trinity Place/Church Street, Broadway, and William Street, a subway line runs under Nassau Street, a BMT line built in 1913 that crosses the Williamsburg Bridge and then an el running down Brooklyn’s Broadway, then on Jamaica Avenue, terminating at Parsons Blvd. and Archer Avenue. The Nassau Street BMT is probably the least patronized of downtown Manhattan’s north-south subway lines, and has suffered some deterioration over the years, especially evident at the Chambers Street station.

The first building seen when walking north on Nassau Street from Wall is, of course, Federal Hall, completed in 1842. This building replaced the second NYC City Hall, built here in 1700 and later remodeled extensively in 1788-1789 (by Pierre L’Enfant, the architect/urban planner who laid out Washington, DC) when it became the first United States Capitol building, a function it held for one year. George Washington took his oath of office as President at that building. It came to be called the original Federal Hall.

The old Federal Hall gradually fell into disuse and disrepair, and it was sold and subsequently demolished in 1812. Thirty years later, in 1842, the United States Customs House was built on the spot, joining the likewise Greek Revival U.S. Assay Office that had been built from 1823-1826. The old Assay Office was demolished in 1915, but it’s still recalled by a sidewalk plaque, and its façade was dismantled and later reconstructed in the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue.

John Quincy Adams Ward’s monumental Washington sculpture was dedicated in 1883. There is a smaller bas relief of Washington in prayer at Valley Forge on the right side of the steps, dated 1907.

For me, a curious aside at Federal Hall is a plaque featuring the state of Ohio. It commemorates the Ohio Company of Associates, consisting of former revolutionary war officers and Massachusetts soldiers, formed in 1786 to plan the purchase and settlement of lands along the Ohio River. Massachusetts attorney and minister Manasseh Cutler negotiated with Congress, which passed the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 that divided the western lands into territories. Cutler and partner William Duer negotiated two contracts that led to the settlement of Ohio with the first settlement at Marietta in 1788.

Nassau Street, as seen from Liberty, runs generally north. Like the parallel Gold Street, it takes a couple of angles from a straight line, and also has some gentle dips (they’re too shallow to be called hills). All that probably speaks to the presence of a stream along which Nassau Street was laid out in the 17th Century.

At the NW corner of Liberty and Nassau is the Federal Bank Reserve of NY Building [York & Sawyer, archs], completed in 1924 and consisting of Indiana limestone and Ohio sandstone. Five stories are below street level with subterranean vaults, containing the gold reserves of many nations, resting on bedrock. There is more monetary worth stored here (over $90B) than in Fort Knox, Kentucky. The bank is the foremost in the dozen that make up the Federal Reserve System.

Around 2000, an organization called the Downtown Alliance was commissioned to produce street signs and billboards featuring local highlights for the tourist trade. The street signs are distinctive, black and white with a font easy to read (it’s one of the new fonts whose name escapes me), and a house number guide, but the standout feature is a photo of a nearby landmark, in this case Federal Hall and the J.Q. Adams Washington sculpture. I wish this could be the model for NYC street signs in all five boroughs.

On the NW corner of Nassau and Liberty is the one-time Sinclair Oil Building. Sinclair used a dinosaur as its mascot, and tall, stylish masonry towers coated with terra cotta like this are dinosaurs in their own right, as most towers built these days are glass-fronted (making them especially vulnerable to windstorms such as Sandy). Later called the Liberty Tower, it was converted to apartments in 1981. Finished in 1910, it seems now like a dry run for the nearby taller Woolworth Tower that came along in 1913. At the entrance, note the pair of alligators tying to shinny up the building.

After running and losing for Vice-President in 1920, Franklin D. Roosevelt worked in this tower for the Fidelity and Deposit Company before entering public life again as NYS Governor and a 4-term US President.

NW corner Nassau and Maiden Lane: 33 Maiden Lane, partially designed by Philip Johnson as a massive office castle in 1986 with corner “tubes.” The Federal Reserve Bank (see above) owns the building.

On a page I did in 2012 on 46th Street, I pointed out a building that’s just 12.5 feet in width. This is wider than that, but it’s still quite narrow. Just south of Maiden Lane, named for the women who used to wash clothes on a now-vanished stream. A number of East Coast streets have Maiden Lanes, but this is the original one.

By some accounts, this building, at 63 Nassau Street south of John Street, was built in the 1860s by an early giant of cast iron architecture, James Bogardus (1800-1874). His use of cast iron to cover building exteriors later led to steel-frame construction. In the Soho area, you’ll find dozens of distinctive buildings with such cast-iron cladding. A short street near Fort Tryon Park in far upper Manhattan is named for Bogardus, far from his architectural innovations.

Note 63 Nassau’s patriotic depiction of Ben Franklin. The empty spaces between the two Franklins on 63 Nassau Street used to contain two similar portraits of George Washington. How or why did Washington disappear? Sloppy renovation, I suspect.

Cockcroft Building, NW corner of John and Nassau Streets. In 1916, a historic plaque was placed on the building by the Maiden Lane Historical Society to commemorate Nassau Street’s association with William of Orange. The plaque read:

Nassau Street

Known originally as

“The Street that Runs by the Pye Woman”

And was named in honor of

The House of Nassau

Whose head at the time was

William the Third

King of England

And sometime Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic

Nassau Street became identified with

The jewelry trade

More than half a century ago.

Erected by the Maiden Lane Historical Society, 1916

Since I only researched this after passing by I don’t know if that plaque has survived the years.

The Cockcroft Building went up in 1907, but the land had been owned by the Cockcroft family since the colonial days.

Nassau Street from John north to Spruce is a pedestrian mall during the week. It’s lined with lunch places, variety stores, clothing shops, that attract the office workers from other downtown streets. Nassau used to have a couple of strip joints that brought in the Wall Streeters at lunch hour but I didn’t see any of them on this 2012 walk. Nor did I see any sort of jewelry row as there was in 1916. Nassau Street had also been renowned for its stamp dealers over the years, beginning in the Roaring Twenties, but they seem extinct as well.

The John and Nassau Downtown Alliance signs here show the tall-masted ships of the nearby South Street Seaport, along with the Brooklyn Bridge. John Street is named for John Haberdinck (or Harpendinck), a local shoemaker during the Dutch days before 1664.

This has been a billboard for a midpriced women’s clothing store for a number of years, but the abiding mystery for me is what that “L” stands for. It’s the same script L that Laverne sewed onto all of her outfits on Laverne & Shirley.

Now, back in the 1870s, they were building incredible edifices. This one took a good 20 years to get right. The Bennett Building, on the NW corner of Fulton and Nassau, was 6 stories with a mansard roof when first built, was raised to ten stories in 1888, and extended north to Ann Street (second photo) by 1891. There’s a texture here with the recessed front windows and curved corner windows that can’t be matched by today’s glass boxes. The Bennett family produced James Gordon Bennett who ran the New York Herald; Bennett sent reporter Henry M. Stanley to Africa to find missionary/explorer/abolitionist David Livingstone in 1871.

Handsome 1890s-era building, SE corner Fulton and Nassau.

On the southwest corner of Fulton/Nassau is the Fulton Building (1891) classified as a Renaissance Revival building with brick, limestone and terra cotta. It was designed by the same architectural firm that later built the Macy’s flagship store at Herald Square.

The Keuffel & Esser Building, 127 Fulton Street, is shrouded in scaffolding as of 2012, hiding its rich architectural details. The building is landmarked, so they should still be there when the scaffolding comes down.

Architects DeLemos and Cordes used this as a dry run for their later, more massive edifces, the Siegel-Cooper and Macy’s department store buildings on uptown Ladies’ Mile. Above the ground-floor storefront here, you can see the cast-iron detailing: renderings of drafting implements and for some reason, a winged wheel.

For decades, before the era of pocket calculators, if you had to figure a complicated mathematical equation, you needed a slide rule, and that’s what Keuffel and Esser, K & E, produced. The company, established in 1867, also made compasses, transits, surveying equipment and other instrumentation, and are still going strong.

A very faded at for K&E can be seen on this building on Ann Street around the corner.

Keuffel & Esser

Drafting materials

Surveying instruments

Measuring tapes

Another of Nassau Street’s smaller buildings, No. 86 1/2, just south of Fulton.

There is yet another faded ad above it, but all I can make out is the address, 86 Nassau Street.

#1 World Trade Center, under construction in 2012 looking east on Fulton Street. Late in the year, afternoon sun glances right off it, producing, in effect, another sun. This must play havoc on westbound Fulton Street traffic, especially if the sun visor is ineffective.

Ann Street was named for the wife of Captain Thomas White, an 18th Century landowner, and runs through his former property. White Street, uptown in Tribeca, is also named for Thomas White, though Thomas Street is not; it was named for a member of the Lispenard family.

Theatre Alley issues north from Ann Street west of Nassau and runs 1 block north to Beekman. For the past few years it’s been adjacent to construction as a new building arises on Ann, and #5 Beekman (see below) is under renovation. Perhaps, it will be revitalized as its cousin, Extra Place, was uptown.

From FNY’s downtown alleys page:

Theatre Alley, running from Ann to Beekman just east of Park Row, at one time was the back entrance to the old Park Theatre (originally the New Theatre), which fronted on Park Row. It stood from 1798 to 1820; after a fire the theatre was rebuilt the next year, and stood till 1848, when it once again burned down. At that time the Park Theatre was beginning to lose out to other theaters springing up along the Bowery uptown. The Astors, who owned it then, elected to not rebuild it.

John Howard Payne, composer of “Home, Sweet Home” was a frequent performer at the Park as a dramatic actor, as wasEdmund Kean and his son Charles Kean, Junius Brutus Booth (father of famed actor Edwin Booth and Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth) and Tyrone Power (1795-1841), an antecedent of the famed screen actor of the 1930s and 1940s. Charles Dickens was feted at the Park on a visit to New York in 1842.

Today Theatre Alley is nondescript and usually covered by scaffolding; I happened by on a day when the usual scaffolds had been removed, looking north from Ann Street. For several years a curious stencil has appeared on a building wall near Beekman advertising the Victoria Theatre, with “vaudeville’ and “photoplays” added. It’s just an art project, originally done for a movie shoot, since there was never a Victoria Theatre here, and certainly never a movie theater. The stencil is reminiscent of the old marquee for Variety Photoplays on 3rd Avenue and East 13th, razed in 2005. Mapping Theatre Alley

#12 Beekman, originally the Morse Building, NE corner of Nassau, completed in 1880 with a 1902 addition. The 10-story Morse Building is one of New York’s earliest surviving high-rise office buildings and was one of the first ‘modern’ tall buildings. It was built as a speculative venture by the nephews of Samuel F.B. Morse, whose early experiments with the telegraph were conducted on this site.

Potter Building, NW corner of Nassau and Beekman. Completed in 1886 [Norris Starkweather, arch.] , this was one of the first towers in Manhattan to extensively employ terra cotta on its facade. It was preceded by the headquarters of the New York World newspaper, which burned down in a scene vividly recounted in in Jack Finney’s fantasy novel Time and Again (why wasn’t it ever filmed?) The Potter Building was also the first NYC buildings to be thoroughly fireproofed (by its developer Orlando Potter).

At the SW corner of Nassau, Temple Court (or #5 Beekman) has been called one of NYC’s lost treasures. Completed in 1883, it joins the Potter Building as an early adopter of fireproof building methods. Amazingly, its nine-floor atrium with cast-iron balustrades was completely abandoned for many years. It’s being redeveloped now, after many years of neglect. The building was built by banker/Irish immigrant Eugene Kelly, who had amassed the nineteenth-century equivalent of $630 million by the time he died.

Many of New York’s foremost urban photographers have been granted access to the amazing atrium and have produced photos of this space that are truly incredible.

I almost forgot the cigar-store Indian at the cigar store on Beekman and Theatre Alley.

Because of the general illiteracy of the populace, early store owners used descriptive emblems or figures to advertise their shops’ wares; for example, barber poles advertise barber shops, show globes advertised apothecaries and the three gold balls represent pawn shops. American Indians and tobacco had always been associated because American Indians introduced tobacco to Europeans, and the depiction of native people on smoke-shop signs was almost inevitable. As early as the seventeenth century, European tobacconists used figures of American Indians to advertise their shops.

Because European carvers had never seen a Native American, these early cigar-store “Indians” looked more like black slaves with feathered headdresses and other fanciful, exotic features. These carvings were called “Black Boys” or “Virginians” in the trade. Eventually, the European cigar-store figure began to take on a more “authentic” yet highly stylized native visage, and by the time the smoke-shop figure arrived in the Americas in the late eighteenth century, it had become thoroughly “Indian.” wikipedia

Approaching the north end of Nassau Street, the Municipal Building at Centre and Chambers Streets comes into view.

I can never resist photographing the last wall-bracket Bishops Crook post left in Manhattan, especially today when the sun was shining directly on it. It is affixed to the rear end of a Pace University building that originally was the home of the NY Times newspaper, constructed in 1889 [George Post, arch.] After the Times moved uptown in 1905, the building gained a couple of floors. Pace purchased it in 1952.

Looking south from Spruce Street, the old NY Times building is on the right and the American Tract Society Building (1894) is on the left.

The American Tract Society Building, at the southeast comer of Nassau and Spruce Streets, was constructed in 1894-95 to the design of architect R. H. Robertson, who was known for his churches and institutional and office buildings in New York. It is one of the earliest, as well as one of the earliest extant, steel skeletal-frame skyscrapers in New York, partially of curtain-wall construction. This was also one of the city’s tallest and largest skyscrapers upon its completion. NYC Landmarks Designation quoted on NYC Architecture.

The Society was founded in 1825 and published religious articles and pamphlets, or tracts.

Pace University fronts on a closed section of Nassau Street just before it reaches Park Row. The school was founded in 1906 by brothers Homer St. Clair Pace and Charles Ashford Pace. The school, which early on was known as Pace Institute, originally rented rooms in the now-demolished NY Tribune Building on Park Row. Ground was broken for the current campus, One Pace Plaza, in 1966. It was approved for university status by the NYS Board of regents in 1973. The University has bought up other space in lower Manhattan and also has a campus in upstate Pleasantville. Pace has about 950,000 square feet of space in Lower Manhattan.

From my Who Are Those Guys? page on the statuary of Lower Manhattan:

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (1706-1790)

Location: Pace University, Park Row and Spruce Street

Sculptor: Ernst Plassman

Year installed: 1872

Ben Franklin’s presence on Park Row is one of the last vestiges of Park Row’s former claim to fame as ”Newspaper Row.” At one time, the New York World, Sun, Journal and Tribune all were located on this section of Park Row, as well as the German language Staats Beitung. Most of them moved uptown after 1900. Some of their buildings, as well as this statue, are still here.

Why Franklin? Before becoming a scientist/ educator/ diplomat/ inventor, Franklin was a printer by trade. He spent a brief time in NYC as a printer’s helper at age 17, but his greatest success as a printer and publisher, and later an editor, came in Philadelphia.

It was in the spirit of Frankiln’s overwhelming success with the printed word (he was able to retire from the business at age 42) that this statue was placed in what was known as Printing House Square in 1872, as a gift from Benjamin DeGroot.

I’ll wrap up FNY’s Nassau Street page with a view of a 1940s-era sign stanchion on Park row and the Brooklyn Bridge approach.

11/11/12