At the very beginnings of Forgotten NY in 1998, I went around Manhattan, as well as the other boroughs, taking pictures of obscure alleyways, which have been a favorite subject of mine for decades. You never know what kind of obscurities might be lurking in alleys, from ancient signage or illumination to an out-of-the -way business. Nowhere else have the changes that have taken place all over the city been epitomized more than in Extra Place, a dead-end on East 1st Street near the Bowery that has gone from a rubble and garbage-strewn alley to a chi-chi enclave of upscale boutiques in just a quarter-century.

I have been going around photographing them again in 2012, in great part because the photos I took back in 1998 were limited by the technology at hand then and the fact that I was an inexperienced photographer and a lot of them came out bad. I don’t pretend to be a pro with the camera even now, but I’m experienced enough to know a few tricks and I have a better camera with plenty of gadgetry I’ll never fathom.

Most of Manhattan’s obscurer alleys, from Extra Place to Cortlandt Alley to Staple Street are aligned north-south against the grid. Jersey Street unusually runs east to west, from Mulberry across Lafayette, ending at Crosby. It was apparently laid out as early as the 1820s and for a short time was called Columbian Alley (a poetic name for the USA is Columbia, for the sailor of the ocean blue in 1492). In 1829, the name was changed to Jersey Street — perhaps one of the neighbors was from the English Channel island of the same name.

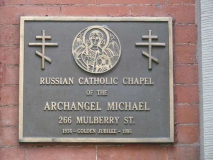

Working west from Mulberry Street, opposite Jersey Street on Mulberry is St. Michael’s Russian Catholic Byzantine Church and its churchyard. The church has occupied this building since 1936–it was built as Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral Chancery Office, which kept parish records and archdiocesan records, and completed in 1859, designed partially by James Renwick Jr. who later designed the much grander uptown St. Patrick’s Cathedral on 5th Avenue.

“Great Vespers” is the sunset evening prayer service of the Byzantine Church, as well as other denominations. The word is from a Latin term meaning “evening star.”

Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral, at Mulberry and Prince Streets, dates back to 1809-1815. From my Old St. Pat’s page:

St. Patrick’s “old” Cathedral, 260-264 Mulberry Street between Price and East Houston, is called “old” to differentiate it from its “newer” cousin uptown, St. Patrick’s Cathedral at 5th Avenue and East 50th, designed by James Renwick Jr., opened 1878 and finished in 1888. Old St. Pat’s, NYC’s original Catholic cathedral, is quite a bit older, having started construction in 1809 and completed in 1815, making it one of the oldest buildings in Chinatown/Little Italy. In March 2010 Pope Benedict XVI announced that it would become Manhattan’s first basilica, a church that has been accorded certain specific and cereminial rites only the Pope can bestow…

St. Patrick Youth Center, Mulberry a little north of Jersey Street, also is associated with Old St. Pat’s, and appears to have come along in the 1930s, as its no-nonsense streamlined design and Machine Age lettering seems to attest.

Between Lafayette and Mulberry, Jersey Street is the southern end of the handsome Puck Building. The famed edifice takes up the entire block between Lafayette, Mulberry, the alley Jersey Street and East Houston. It was built as a printing plant between 1886 and 1893 by the publishers of the satirical magazine published between 1877 and 1918. In the 1980s it was home to both the New York Press weekly and Spy Monthly, though both have long since vanished in their print versions, anyway. Some of the Puck Building was shaved off when Lafayette Street was extended south in the early 1900s, and even now, the back edge facing Jersey Street isn’t as well appointed as the Mulberry, Houston and Lafayette Street facings.

The ground floor of the Puck Building has been home to a succession of the hotter boutiques of the moment.

Buildings that face back alleys, like the Puck Building, that were built between 1880-1920 often feature metal shutters on the windows — it was thought to be a fire retardant.

The New York Public Library Mulberry Street Branch is housed on the ground floor of this building on the south side of Jersey between Lafayette and Mulberry. Its address is given as #10 Jersey, one of two addresses on the alley. The branch’s website indicates the building is a former chocolate factory.

Not sure what’s going on up on the roof, but it looks pretty incongruous.

Lafayette Street effectively cuts Jersey Street in two sections. Lafayette Street is only about a century old, making it an interloper in these parts. It began as Lafayette Place, a block-long enclave between what is now Astor Place and East 4th on which millionaire fur trader John Jacob Astor’s son William B. Astor built mansions for himself and his sisters (the now-deteriorated Colonnade Row is a reminder of the Place’s former grandeur). In the early 20th Century (I can’t pin down the year but it may have had to do with the construction of the IRT Lexington Avenue Line, the 4/5/6 train) Lafayette Place, now Street, was extended south, enveloping the former Marion and Elm Streets, joining with Centre Street at Foley Square.

For more on Colonnade Row, see FNY’s Car-Free Saturday Part 2 page.

Above: looking west toward Crosby Street.

Several ancient manhole covers can be seen on this stretch of Jersey Street, including this one bearing the abbreviation MANHATTANBOR, indicating it was placed after 1898, when Manhattan became one of the 5 boroughs. An even more ancient cover, placed in the 1860s in the years after the Croton Aqueduct was constructed, has since been removed, but I got a photo of it in late 1999 and placed it here.

The only other address on Jersey Street beside the library is #1, outside of which is this painted admonition. Weehawken Street in the West Village has similar signs, as back alleys often substitute as pissoirs due to NYC’s paucity of public bathrooms.

To me, Crosby and Jersey is a quintessential NYC intersections, one back alley meeting another. Opposite Jersey Street a couple of buildings house the expanding Housing Works, encompassing both a thrift shop and a used bookstore/cafe. Proceeds from sales go toward housing and related supportive services to low-income and homeless New Yorkers living with HIV/AIDS.

While some NYC intersections could do with more or clearer traffic signs, the obscure Crosby/Jersey intersection boasts two STOP signs and two pairs of One-Way arrows. It’s possible there were a few accidents here as traffic in these narrow streets has gotten busier over the years.

In these parts, no available surface on the ‘street furniture’ is wasted. This battered fire alarm features stickers with messages and services, plain old graffiti, and topped with a street art portrait.

I haven’t been able to find out about the history of this handsome brick building on the corner, but it was likely used as a loft or for manufacturing. When such a building is constructed today, there’s no flair whatever, unlike how they handled it between 1880-1920.

More and more signs employing the new Clearview font have shown up in NYC the past few years. The font has been replacing the old Highway Gothic family on highway signage, because of its purported easier readability. There had also been a federal mandate, since delayed or rescinded, that specified that Cap-Lowercase lettering be used on street signs. However, the Department of Transportation increasingly flouted the regulation, and so you have all-cap Clearview signs replacing perfectly readable all-cap Highway Gothic signs. A waste of money.

Looking east on Jersey Street all the way to St. Michael’s.

Crosby Street has been able to keep its old brick paving along the majority of its length. The street is named for early 19th Century philanthropist William Crosby.

Between Jersey Street and East Houston is a colorful Benetton fashion store (the chain for many years has billed itself as “United Colors of Benetton” and it has always had a slightly edgy appeal in its advertising). Two dummies are positioned in the act of love on the roof.

Before kicking it in the head for today’s survey I couldn’t resist snapping the Cable Building on Broadway and west Houston. The building contained works that powered Manhattan’s cable cars in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Yes, Manhattan once had an extensive system of cable cars rivalling San Francisco’s. The building housed the enormous machinery that was necessary to run the cars in Manhattan as far north as 36th Street. The cable rails were converted to electricity in the early 1900s, and largely eliminated by buses by the 1940s.

12/9/12