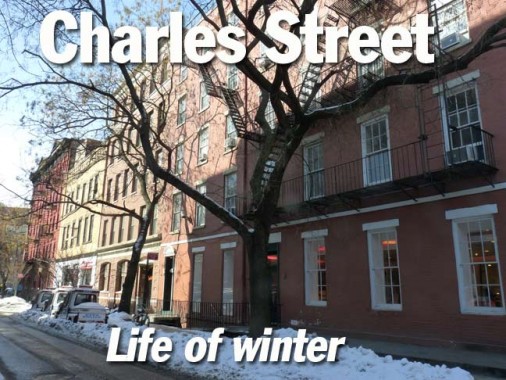

Charles Street runs from Greenwich Avenue to West Street just north of West 10th. The principal heir of Sir Peter Warren, who owned the land where Charles Street is found in the colonial era, was a fellow named Charles Christopher Amos, and those names were applied to streets when they were built through the area by 1800. Amos Street became a western extension of West 1oth Street in 1857. In early February I entered the Village, which had become Kadath in the Cold waste after a succession of days in the teens and several snowstorms, because the cabin fever was becoming too much. After my tearducts reacted to the cold inopportunely and my eyes were repeatedly annoyingly blurred, I scurried back indoors, but not before squeezing off some photos of the West Village in winter.

Most of the buildings on Charles Street went up between the 1850s and 1890s, with a couple of older and younger exceptions. #11 Charles Street for two years (1925-1927) was home to journalist/crime novelist James Cain, three of whose books became major motion pictures: The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), Double Indemnity (1936) and Mildred Pierce (1941). Cain was born in Maryland and in his youth reported for the Baltimore American and Baltimore Sun, where he befriended his mentor, H.L. Mencken. During his two year in NYC he was an editorialist for the New York World and later The New Yorker; he moved to southern California in 1932, but other writers adapted his novels for film.

“I make no conscious effort to be tough, or hard-boiled, or grim, or any of the things I am usually called. I merely try to write as the character would write, and I never forget that the average man, from the fields, the streets, the bars, the offices and even the gutters of his country, has acquired a vividness of speech that goes beyond anything I could invent, and that if I stick to this heritage, this logos of the American countryside, I shall attain a maximum of effectiveness with very little effort.” Preface of Double Indemnity

#39 Charles Street, the building in the center behind the tree, was home to the “Little Flower,” Fiorello LaGuardia, from 1914 to 1921. He is rightly famed for his tenure as NYC Mayor from 1934-1945, but while living here, he became Deputy Attorney General of New York in 1915, and in 1916 was elected to the US House of Representatives and served there until December 31, 1919. During World War I LaGuardia joined the US Army and rose to the rank of major in command of a unit of bombers on the Italian-Austrian front. In 1919, LaGuardia ran as a Republican for the President of the NYC Board of Aldermen (the equivalent of today’s City Council President) and won. He returned to Congress in 1922 and served eleven years before his election as NYC mayor.

Though there are new versions of Bishop Crook lamps by the thousands in NYC these days, at the corner of Charles and West 4th is a bishop crook remnant — just the base is remaining from a former Type 6 BC (for Bishops Crook). Type 6’s are recognizable by their thinner bases, as they were generally deployed on narrower streets and sidewalks. This remnant used to list noticeably until restored to an upright position several years ago. There’s only one Type BC in working condition remaining — and that’s a restored lamp on Warren Street in Tribeca.

Until 1936, an unusual condition existed on Charles Street between West 4th and Bleecker Streets — the north side of the street, and only the north side of the street, was called Van Nest Place (after a former estate) and had its own separate house numbers. In 1936 the entire street, on both sides, became Charles Street. This kind of arrangement was once common but can’t be found in NYC anymore, although there is an unusual arrangement for Leroy Street in the Village, which turns in to Saint Lukes Place between 7th Avenue South and Hudson Street at a bend in the road between the two streets. Leroy Street resumes west of Hudson Street.

#53 Charles Street (formerly #2 Van Nest Place) is the Congregation Darech Amuno synagogue. As with many of the buildings in Manhattan that catch my eye, the Daytonian in Manhattan has been here before me:

… Established in 1838, the Dutch congregation had moved throughout the 19th Century from Greene Street, to 99 Sixth Avenue, to 7 Seventh Avenue, to 278 Bleecker Street, to a synagogue on West 4th Street, before purchasing the 1868 house on quiet Van Nest Place in 1912.

Rather than starting from scratch, architects Sommerfeld & Steckler altered the existing structure. The five-year renovation gutted the townhouse. What resulted was a three-story classically-inspired structure that hugged the property line. The nearly-flat fronted Roman design included a classical pediment and brick pilasters supporting stone cornices between each floor. The colorful stained glass of the dominating rose window, hefty fanlight over the entrance and six flanking windows highlighted the cream-colored brick trimmed in limestone.

The small synagogue is an unlikely concert venue, offering bluegrass and roots music.

Minnesotan author and playwright Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951) lived at #10 Van Nest Place, now #69 Charles Street, from 1910-1913, well in advance of his literary success with Main Street (1920), Babbitt (1922), Arrowsmith (1925), Elmer Gantry (1927), and Dodsworth (1929).Lewis turned down the Pulitzer Prize for Arrowsmith but accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1930. In 1935 he published It Can’t Happen Here, a speculation about the election of a fascist to the US Presidency. Arrowsmith, Elmer Gantry and Dodsworth were made into acclaimed motion pictures.

Folksinger Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) is perhaps famed more for living on Mermaid Avenue in Coney Island in the 1940s and 1950s in a building that has since been knocked down, but before arriving there, he briefly lived in this building (12/42 to 5/43) at #74 Charles Street, where a plaque has been installed by the Historic Landmarks Preservation Center. Guthrie, along with Pete Seeger, was a member of the Almanac Singers, who lived communally nearby at #130 West 10th Street, which they called The Almanac House; “Almanac” was inspired by the Old Farmer’s Almanac. The singers’ leftwing views earned them investigations by the FBI and they disbanded during World War II, but they re-formed, minus Guthrie but with other additions, as The Weavers in 1950, and enjoyed several top ten classics including their version of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene.”

Hart Crane (1899-1932) is perhaps more associated with Brooklyn Heights, where he spent more time and inspired his most famous poetry works, “The Bridge,” but he lived here at #79 in 1920. Crane’s father was a candy manufacturer and held the patent for Life Savers before selling it for a song, only to see it go through the roof later on. Crane, troubled by alcoholism, committed suicide during a trip to Mexico in 1932.

Two doors down, poet and educator Delmore Schwartz (1913-1966), lived at #75 Charles from 1948-1951 while teaching at the New School. Schwartz was a major influence on the career of Lou Reed.

Dodging around the corner to #393 Bleecker Street, which doesn’t look like much to write home to Mother about on the exterior, but opens up to a wide courtyard on the interior. In the late 1920s, literary professor/author/poet Mark Van Doren agreed with like-minded neighbors to take down the back fences separating their properties that faced Perry and West 11th Streets and created a mutual yard shared by all. Van Doren was associated with Columbia University for over 50 years, between 1920 and 1972, mentoring Allan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and other poets who later became part of the Beat generation. At least one of the houses surrounding the so-called Bleecker Gardens was built before 1820.

Mark Van Doren’s son, Charles, competed successfully in 1959 on the Twenty One quiz show — before it was revealed that the show’s producers were slipping him the answers in response to his popularity. After the scandal broke, Van Doren moved with his family to Chicago, where he worked as an editor with the Encyclopedia Britannica.

I’m showing this oddly-shaped (and probably very old) brick town house at Hudson and Charles Streets because a detailed map of Greenwich produced in 1961 by Lawrence Fahey that I acquired in the summer of 2013 has this as the location of the Lion’s Head Café Espresso. My understanding was that the Lion’s Head Inn was opened around the corner on Christopher Street from 1966 to 1996, so why would it be referenced in 1961? And why here?

120 Charles, between Hudson and Greenwich, was the home of journalist/poet/playwright Holly Beye (1922-2011) in 1949-1950, some of whose essays were collected in 120 Charles Street, The Village. The work had been lost for over fifty years, after Beye and her husband David Ruff moved to San Francisco, until it was rediscovered and published in 2006.

It appears as if 121 Charles , at the corner of Greenwich, has been here forever but it is actually a 1967 interloper. It is an 1809 farmhouse moved here by Sven and Ingrid Bernhart after it was discovered after a demolition on York Avenue and East 71st Street, and trucked downtown to this spot on March 6th of that year, along with some of the cobblestones adjacent to it: hence the building’s nickname “Cobble Court.” While uptown it had been the home of author Margaret Wise Brown (1910-1952; Goodnight Moon).

The building hasn’t been landmarked, as the Landmarks Preservation Commission sometimes doesn’t designate buildings that have been altered considerably from their original condition.

Unfortunately, in February 2014 both #131 (left) and #129 Charles Street were covered by netting and acaffolding as they underwent renovation. Hopefully the horse’s head and “H. THALMAN” on the outside of #129 will be retained — the building is a former stables. Though Herman Thalma(n)n’s stables only lasted a single year (1898-1899) the sign has been there since that time.

#131 is the older of the two, a Federal-style townhouse built in 1834.

There is a back house, #131-1/2, completely invisible from the street, accessible from the doorway in shadow at lower left. Famed photographer Diane Arbus lived in a converted stable here: her photographic portraits, mostly done in the 1950s and 1960s, captured an America that was decidedly different from the pleasant postwar period that major publications put forth for public consumption. Her husband in the 1950s, fashion photographer Allan Arbus (1918-2013), later turned to acting and played the kindly psychiatrist Dr. Freedman on the M*A*S*H TV version in the 1970s.

At 135 Charles Street near Washington is one of the more monumental police stations you’ll ever see. The grandeur was probably lost on the cops and crooks who went in and out of here every day. It was originally the 9th Precinct, designed by John DuFais and built in 1897, an era when most of NYC’s grandiose works went up. The precinct moved to a blander building on West 10th in 1972, becoming the 6th Precinct; as long ago as 1978 the Number 9 was converted to apartments, beating the old NYPD Headquarters on Centre Street in that regard. It is now known as Le Gendarme. It boasts what is probably one of the larger sculptures of the NYC Seal you will see on a building, though this one is a variant of the usual one (the Dutch sailor is holding an oar instead of a plummet).

Because of the snow, ice and construction across the street, I couldn’t get a good full-on view of #159 Charles, between Washington and West, so two side views will have to suffice. It was constructed in 1838 for merchant Henry Wyckoff. Overshadowed by the Richard Meier glassy apartment towers at Charles and West Streets, #159 and #161 are the only two 19th Century townhouses remaining on the block. Of the nine lots owned by Wyckoff on the block, only this one is here now. Ivy covers the outside wall in spring and summer.

Crazy from the cold but not yet willing to call it a day I stumbled up Washington Street and then at West 11th I encountered It:

Bear in mind I had yet to witness in person this monstrosity named Palazzo Chupi, executed atop a former stable building by artist/filmmaker Julian Schnabel. I had heard about it. It’s a pink Italianate tower rising about 100 feet above street level, dwarfing the other buildings on the block. Completed in 2008, original selling prices for some of its residential units (interiors here) rose as high as $32 million, which was later knocked down to “just” $12 million. (Honestly, where is all this scratch coming from?)

In the Palazzo’s shadow is a Greek Revival townhouse, #354 West 11th Street, built in 1842 for architectural ornament manufacturer William B. Fash on the site of a former soap factory. Everything else on this block has changed, even the building address and name of the street. This was originally 144 Hammond Street, but in the mid-1800s several Village street names were dropped and made western extensions of the numbered streets West 4th, 10th, 11th and 12th.

Shingle signs are the latest trend in advertising and scaffold signage. This one, for the 11th Street Cafe, is even handsomely embossed.

321 West 11th, hoisting a Chinese laundry on street level, looks like a slice of the old Village before it was all riched up. #321 was the home of author Carson McCullers (1917-1967) in 1940, when she wrote her best-seller, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, at just 22 years of age.

Thomas Wolfe lived at #263 West 11th between Bleecker and West 4th, from 1927-1828, finishing Look Homeward, Angel there; and Jack Kerouac worked on On the Road at his girlfriend’s apartment at #307, a building set back from the street, later owned by celebrity photographer Annie Liebowitz.

This building at Greenwich Street and West 11th is better seen in spring and summer, when it is covered in ivy.

Shifting over to Perry Street, the Spanish-style townhouse at #93, just off Bleecker, has a special place in the heart of H.P. Lovecraft fans. A courtyard leads to a back house, which is the supposed setting for one of the Ghostly Gentleman’s short stories written in 1925 during the Providence native’s “New York Exile.” In “He,” the narrator, roaming around the Village at night, meets a strange man professing to be a historian and antiquarian who has the ability to reveal Village scenes from centuries ago and also from the future. The two run into trouble when they disturb Native American spirits.

Perry Street: “Dog of the Ilk”

The Greenwich Village LPC Report is curiously silent on 48 Perry Street’s pair of iron dragons that guard the front entrance.

At #33… This distinguished brick building resembling a library has been, since 1926, a house with four high-ceilinged apax orients, but it was built as a stable in 1897. It is a very handsome transitional building, basically Romanesque Revival in style. It shows elements of design which herald the new classicism then coming into vogue, as may be seen in the brick quoins and in the deep roof cornice with horizontally placed console brackets. LPC Report linked above

#28 Perry Street, built as a 5-story brick apartment building in 1899, has a distinctive arched front entrance door with Corinthian-style pilasters that is likely the original.

Perry Street and Greenwich Avenue, where construction cranes signify more of the old Village going away.

Information in this page from Alfred Pommer and Eleanor Winter’s Exploring the Original West Village (though beware, they claim Arbus lived at 121-1/2 Charles, not 131-1/2 Charles.)

3/16/14