This week I was looking at some photos of the Brooklyn waterfront that I took in 2011 along Furman Street. At that time, Brooklyn Bridge Park had been built out only along the end of Old Fulton Street at Pier 1 (the waterfront from Atlantic Avenue to Old Fulton is made up of Piers 1 through 6). Work was just beginning on Piers 2 through 6. These days, the park has more or less been opened all the way down, and while Piers 1, 2 and 6 are finished, the others are still under construction, and a couple of high rise residential projects have gotten started but have been tied up in court. In addition, the city opened sections east of the Brooklyn Bridge all the way to John Street. A pedestrian bridge has been opened and closed because its swaying was making people seasick.

All this has been met with a great deal of hoopla and press (gallons of ink are no longer being spilled, but trillions of cyberpixels are) and while the nearly complete Brooklyn Bridge Park is a marvel of urban engineering, I’m reminded of a large piece of recreational Brooklyn waterfront that has chugged along with only rare fanfare since 1940, when it was created along with the Belt Parkway in southern Brooklyn and Queens. This waterfront park has no real name, but is simply called the “Bay Ridge bike path” or “Shore Road bike path” by residents.

I was in Bay Ridge for lunch with a cousin when I decided to walk down the “bike path” where I had traveled so many times in my 35 years in the neighborhood. The section I’m most familiar with runs from the 69th Street Pier, where ferries to Staten Island ran until 1964, to Ceasar’s [sic] Bay Bazaar, the former E.J. Korvettes site that has become a conventional shopping mall. Since I was on 4th Avenue, I just walked the section as far as Ceasar’s Bay, then through Bensonhurst to the train.

The southeast corner of 4th Avenue and 101st Street is marked by the Bridge Hamilton condo development and the Lai Yuen Chinese restaurant. For decades, though, this spot was where Hamilton House, a restaurant I had been past hundreds of times alone or with my parents, but had never eaten (The also-vanished Tiffany Diner on 99th and 4th was where we went). My cousin and I ate at the Narrows Coffee Shop at 100th Street, which shows up in this photo from 1963.

Hamilton House was torn down for the condos in the late 1980s, but this lone lamppost at 101st Street may be its only legacy.

John Paul Jones Park, sometimes called Fort Hamilton Park and Cannonball Park, is named for American Patriot and Naval hero, John Paul Jones (1747-1792), who, through victorious leadership in the American Revolution, became known as “the father of the Navy.”

Enlisting in the newly established Continental Navy in 1775, Jones distinguished himself as captain of the sloop Providence, as First Lieutenant of the flagship Alfred and Captain of both the warships Ranger and Bonhomme Richard. On September 23, 1779 Jones’s ship slipped into the midst of a British mercantile convoy. In attacking the convoy’s escorts, the H.M.S. Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough, Jones’s smaller vessel suffered severe damage. His vessel afire and sinking, Jones refused the enemy’s demand for surrender, replying “I have not yet begun to fight.” Three hours later, the Serapis surrendered.

After this and other Revolutionary War victories, Jones received honors from all over the world, including a gold medal from the newly formed Continental Congress, and a gold-hilted sword from King Louis XVI who made him a chevalier of France. NYC Parks

The park is named “Cannonball Park” for the longtime presence of a 20″ Rodman gun and several cannonballs on the 4th Avenue side, one of two tested at Fort Hamilton but found unsuitable for combat. Streets surrounding Fort Hamilton, such as Dahlgren, Parrott and Gatling Places, are named for inventors of military ordinance.

A Revolutionary War Memorial in John Paul Jones Park consists of a bronze tablet on a granite boulder that New York City received from the Long Island Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1916. The first resistance to British troops by the Continental Army took place in this vicinity during the American Revolutionary Battle of Brooklyn.

In a park full of war memorials and tributes, the tallest is the Dover Patrol Monument, dedicated in 1931 and designed by Sir Aston Webb. The Dover Patrol was a unit of the British Royal Navy that served during World War I, and the obelisk reads, “this monument to the Dover Patrol erected as a tribute to the comradeship and service of the American Naval Forces in Europe during the World War.” Identical Dover Patrol monuments stand in Dover, England and Blanc Nez, France.

John Paul Jones Park is the site of one of the three 20-inch Rodman guns ever produced. Fort Hamilton, in 1864, tested this new cannon, designed by Capt. Thomas Jefferson Rodman, which weighed 58 tons and fired shot weighing 1080 pounds up to 4 1/2 miles. A derrick had to be used to load the cannon. The cannon’s effectiveness was judged minimal after it failed two trials.

Shortly after being mounted the piece was fired four times with 50-, 75-, 100- and 125-pound charges. In March of 1867 it was again fired with charges of 125, 150, 175 and 200 pounds of powder. At an elevation of 25 degrees a range of 4-1/2 miles, was obtained.

These were the guns that established the International “Three Mile Limit” for Territorial Waters. In the 19th and early 20th century a nation “owned” those waters that it could defend with cannon fire.

One of the three Rodman guns produced wound up here, along with a goodly number of cannonballs in what is commonly known as Cannonball Park. The second was located at Fort Hancock in New Jersey, and is now on display at the Sandy Hook National Park Site, and the third was sold to Peru. Records of this cannon were lost during Peru’s war with Chile from 1879-1883.

While heading onto the pedestrian/bike path at the water edge I spotted this sign directing drivers to Flushing Meadows-Corona Park at the Belt Parkway entrance ramp. It’s somewhat perplexing to find one of these specialty signs, most of which appear in FMCP itself, this far away. I imagine Belt Parkway traffic would connect with the Gowanus Expressway, then the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and then the Horace Harding (Long Island) Expressway to get to Flushing Meadows.

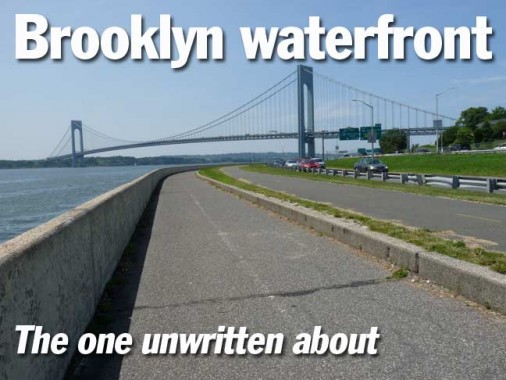

The massive Verrazan0-Narrows Bridge is seen while walking down the pedestrian ramp to the waterfront.

The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge was built in five years between 1959 and 1964. Prior to that, there was no way to reach Staten Island from any other part of NYC except by boat. Ironically, you could reach Staten Island from the mainland via 3 bridges, the Goethals, Bayonne and the Outerbridge. Staten retained very much a small town feel despite these two bridges, though, since a bridge connection from NYC and one from Union County, New Jersey are two separate stories. Staten Island would reap immediate benefits from the new bridge, but Brooklyn would incur immediate losses.

There were long and voluble protests from Bay Ridgers when plans for the bridge were announced. NYC’s master builder, Robert Moses, planned to scythe the long, wide bridge ramp through the heart of the neighborhood in a strip along 7th Avenue. Moses usually got what he wanted, though his plans to build a Battery Bridge and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway through Brooklyn Heights had been derailed and a concurrent plan to build the Lower Manhattan Expressway along Broome Street would eventually be. There was no such reprieve for Bay Ridgers, and fully 7000 residents were displaced.

The bridge is named for Giovanni da Verrazzano, the first European to sail into New York Harbor. Presumably the “z” was dropped from his last name to save a little money on printed materials and signage.

The bridge’s other casualty was the 69th Street Ferry to Staten Island, which closed the day after the bridge opened in November 1964.

This is the view of the Narrows available from the 4th Avenue path down to the bike path. The Narrows is part of an estuary (a body of water found where freshwater and seawater come together) separating Brooklyn from Staten Island and Upper and Lower New York Bays. It is narrower than those two bodies of water, hence the name.

I turned south along the path. In this view, the “ghost” of Denyse Wharf can be seen, along with the traffic ramp connecting the Verrazano approach with the Belt Parkway. At the center horizon, the west end of Coney Island can be seen.

There’s a small outcropping of concrete and riprap jutting into the Narrows, just southeast of the Verrazano Bridge. It used to be a more important pier and actually had direct access from the Belt Parkway, which roars past a few feet away. I had always thought that it was somehow busier in the past, and after researching it I discovered that it’s actually a remnant of the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776.

In the colonial era, before there was a Fort Hamilton or a Belt Parkway, Bay Ridge was a part of the town of New Utrecht. Three of the town’s foremost citizens, Adrian Bennett, Simon Cortelyou, and Denyse Denyse, had homesteads right about here, and Denyse ran a ferry to Staten Island close to his home.

The British and their Hessian and Scottish compatriots under General William Howe chose the Denyse Ferry as the place to land in New Utrecht for a major offensive on August 22, 1776, after massing 437 ships off Sandy Hook by July 12th. The Narrows was relatively undefended since the Americans were expecting a landing at Gravesend. According to legend, a Tory (loyalist) woman waved a red petticoat from Cortelyou’s house to signal the invaders: many New Utrecht residents were loyalists. The patriots had only three cannons on the promontory above the Narrows, and fought vigorously, but the British warship Asia responded by firing a volley that damaged Bennett’s and Denyse’s houses, but curiously, not Cortelyou’s. 15,000 British troops entered New Utrecht virtually unscathed; they were quickly able to overrun Kings County, bivouacking in the various homesteads throughout the locale. Howe commandeered Cortelyou’s house. Denyse himself was a patriot. In 1783, when the British evacuated New York City, they left from the Denyse Ferry landing.

Sometime before the bridge was built the Army maintained a pier here, presumably for collecting supplies from ships in the Narrows. I imagien it was more important when Fort Lafayette, Fort Hamilton’s sister fort along with another sibling, Fort Wadsworth, stood on an island in the Narrows. After the eastern tower of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge was built, supplanting Fort Lafayette, the pier lessened in importance and has been left alone for over 50 years. The protective fence has rusted pretty badly.

The concrete on the traffic ramp has deteriorated badly. I’m sure this location is inspected fairly frequently and if danger was imminent it would be rapidly shored up. Still, it doesn’t make a good impression.

Hoffman Island looms in the Narrows off the eastern coast of Staten Island. Along with Swinburne Island, it is a man-made island in the harbor used in the early part of the 20th Century for military training and quarantining. The islands were converted from existing shoals in 1872 and Hoffman was named for the NYS Governor at the time, John Thompson Hoffman, who has previously served as NYC Mayor. (There’s a Queens connection: before Queens Boulevard was greatly expanded between 1910-1925 in association with the opening of the Queensboro Bridge, it was known as Hoffman Boulevard, and an odd bend at Woodhaven Boulevard is still called Hoffman Drive.)

The buildings on both islands were razed in 1961 and the islands have been maintained by the National Parks Service since then as bird sanctuaries.

In the 1990s, when my father’s girlfriend had a hospital stay at Victory Memorial on 7th Avenue and 92nd Street, I noticed that some of the rooms had a great view of both islands. The hospital, however, closed during the first decade of the 21st Century and is now a clinic associated with the State University of NY.

Traditionally this has been considered a gateway to Brooklyn, as traffic is entering the Belt Parkway via the Verrazano Bridge from Staten Island or New Jersey. Hence, there have been signs here with messages from the current borough president. In the opening credits of Welcome Back, Kotter in the 1970s, Beep Sebastian Leone had a sign here proclaiming Brooklyn the USA’s 4th largest city, which it would have been had it not been absorbed into greater New York in 1898. I’m not sure if Brooklyn would be in 4th place today.

The current sign is a catchphrase from Jackie Gleason, who was born in Brooklyn and played bus driver Ralph Kramden in the 50s and 60s on The Honeymooners and on The Jackie Gleason Show.

This section of the Belt Parkway is featured in the 1978 film Annie Hall, as the title heroine terrorizes Alvy Singer with her reckless driving.

The Parachute Jump, originally constructed as a training device for paratroopers and originally featured as a passenger ride at the 1939-40 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows and later moved to the Coney Island boardwalk, comes into view here, especially if you use a zoom lens.

Looking across the Belt Parkway toward officers’ quarters in Fort Hamilton. It is the only remaining active fort in New York City. During relative peacetime in the 1980s and very early 1990s, I was able to bicycle in without checking in at the gates. These days, I likely couldn’t roam the grounds with a camera except in the Harbor Defense Museum, but I’m safely on the other side of the parkway here.

Looking toward Veterans Memorial Hospital on Poly Place and 7th Avenue, now called Brooklyn Veteran Affairs Hospital. It has not been immune to budget cuts as of late.

When I was a kid we would bundle up old magazines and take them down to the hospital for the infirm veterans to read. Later on, when I worked nights, when I was coming home at Christmas time I would look for the red lights strung on VMH in the outline of a Christmas tree.

When the “bike path” was constructed in the 1930s, large boulders were placed at the water edge to prevent flooding (this arrangement is called “riprap”) but that doesn’t stop especially violent storms such as Hurricane Sandy from severely damaging some sections every winter and some years, a lot of the roadway has to be patched up and the fencing restored in place.

The fencing along the bike path is unique in New York City and runs about the entire length of the walkway. It appears to be made of stainless steel and seems impervious to rust.

When I lived in Bay Ridge this section of the bike path opens up a wide section of green just south of the Bay 8th Street overpass. Formerly, it was used by a large number of kite fliers and toy plane operators. I believe some aviators were complaining about the kites, so the NYPD put the kibosh on the kites.

At Bay 8th Street the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge begins to recede into the distance.

There are a quartet of arched steel pedestrian bridges crossing the Belt Parkway. The two westernmost, at about 82nd and 92nd Streets, have their own unique design, as do the two east of the Verrazano Bridge, at about Bay 16th Street and again at 27th Avenue (which we will see later).

The fencing on the bridge, likely built around 1939, has gently curved handrails with Deco elements.

Best of all this bridge has an intact Type F lamppost, complete with finial. NYC Parks has painted these a grayish blue of late. For several years, the incandescent luminaire on this post was replaced with an inversed park lamp (usually used on Type A and B in parks) that made for a very strange look. In the 1980s, a standard sodium “bucket light” — I don’t know the model number or manufacturer — was placed here.

The NYC Parks department teamed up with various other agencies as well as the New York Aquarium to have a little fun with the barrier fence, installing a couple of informative exhibits. This one, just east of the pedestrian bridge, shows the various waterbirds and predatory birds that can be seen in the area.

Well into the late 1970s, even the 1980s, the Belt Parkway was still well-stocked with the same “Woodie” lampposts it was originally tricked out with when it opened in 1940. However, they weren’t being produced by the 1970s, and when one fell or failed, it was replaced by a Deskey lamp, single or double. Originally the incandescent Westinghouse lamp on the old Woodie was placed on the Deskey, making for an unusual look.

Gradually the Deskeys had had their day and were replaced in the center median by shiny, cylindrical aluminum twin posts manufactured by Flagpoles, Inc. This is the last twin Deskey I spotted on the Belt Parkway in this stretch.

A second informative installation on the railing nearing the bike path’s end at Ceasar’s Bay describes the Narrows estuary as well as the sea life that can be found there.

As stated, the bike path ends at Bay Parkway, at the site of a shopping mall. In the 1960s this was dominated by EJ Korvettes, where we would shop when we weren’t in the mood for a trip downtown to the A&S. After Korvettes went out of business this became a mix of shops called Ceasar’s [sic] Bay Bazaar, which is what I still call the area. These days, Kohl’s, Best Buy, Toys “R” Us, and eateries like Wendys and 5 Guys hold down the strip.

Bensonhurst Park is the largest park in its title neighborhood and straddles both sides of the Belt Parkway. This side has much of the park’s athletic fields.

The southern end of Bay Parkway has a distant view of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

There is still disagreement on how to spell Ceasar’s Bay Bazaar. Brooklynites insist on Ceasar’s, but Latin aficionados go for the original spelling.

In Part 2: a forgotten submarine and the houses built by Stooges.

8/16/15