Downtown Flushing is noisy, overcrowded, and smells horrible.

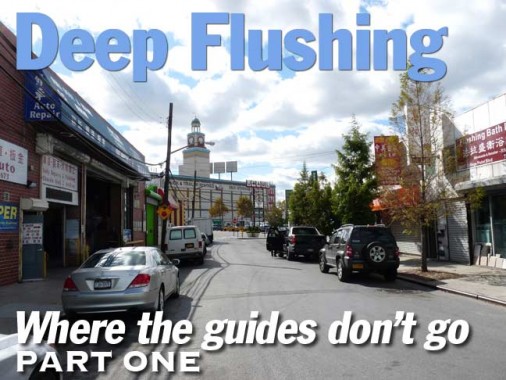

That’s why, naturally, I decided to take my latest voyage of discovery in Flushing in October, when the oderifousness is tamped down just a little. My idea started when I did an item on an obscure lane, Birds Alley, that ceased to be a mapped street decades ago, but its path is preserved by a driveway and by Google Street View, which still duly names it. Thus, I decided to revisit some of Flushing’s labyrinthine jumble of streets — the neighborhood was first settled in the 1630s and many of the roads were built for horses and wagons, not automobiles — and see if there were any surprises there.

There are a few, but one of the things you discover when you revisit a neighborhood with a keener eye, you notice patterns and “designs” you may have missed first, and details that has escaped you years ago stand out of the pack, plain as day, and you have no idea why you didn’t see them in the first place.

I began at a Q12 bus stop (the route connects Flushing and Little Neck) at Roosevelt Avenue and Bowne Street, then followed the route shown toward Flushing’s industrial corridor that nonetheless has some residential and historic buildings sprinkled here and there.

I was introduced to Flushing in 1969; I became a baseball fan that spring, when I was eleven, and my team of choice was the New York Mets, since Ron Swoboda had made an appearance at St. Anselm’s parish in Bay Ridge that preceding winter and I had snagged his signature. It was quite a year to become a baseball fan, since in 1969 the Mets shocked the Cubs, the Braves, the Orioles and the world and became world’s champions. I thought they’d do that every year, but they’ve done it only once since then. I made frequent appearances at Shea Stadium that year, taking a very long ride from Bay Ridge on the RR train (trains had two letters then) and the 7. Now and then I’d look out over the center field fence at the Serval Zipper clock tower and Flushing beyond. The zipper tower, originally a furniture showroom building (see below) has outdated the zipper company and become a Flushing fixture.

The Dutch, led by New Netherland Governor William Kieft, took the region by force from the Indians and warred with them until the English arrived in 1645, on invitation from Kieft, who granted the English a vast 16,000-acre tract that included what is now Flushing. The name is an English transliteration of the Dutch town of Vlissingen. Flushing, though, for most of its history was Dutch-dominated only because Peter Stuyvesant , Kieft’s successor, was its governor during its early history. The Brits named the town in honor of Vlissingen because the town harbored English refugees before they sailed for America.

The Bowne House is here at Bowne Street and 37th Avenue as it has been since 1661 when it was built by British settler John Bowne. Peter Stuyvesant, imposing a reign of terror against religious dissenters, had Bowne, a Quaker, arrested in 1662. Before the construction of the Friends Meetinghouse (see above), Bowne’s house was the primary site for Quaker services. Sentenced to pay a hefty fine, Bowne refused and was jailed; he was subsequently exiled to Holland.

While he was there, Stuyvesant’s bosses at the Dutch West India Company reversed Stuyvesant’s non-tolerant policy, claiming that the colony needed many immigrants to ensure economic expansion, no matter what faith they were. Bowne returned home to Flushing in 1664; the British sailed into New Netherland five months later, and Stuyvesant surrendered without a shot being fired.

The Bowne House has been “closed for renovations” from the public for the better part of twenty years, though it does open its doors for special holiday occasions now and then. A sign out front proclaims that the time is nigh that the Bowne House will again be accepting regular visitors again but, that tune has been played before and until the house does open again, I’ll tune it out.

A few years ago the New York City Economic Development Corporation placed a series of helpful signs at Flushing’s sixteen historic spots along two different trains, green and orange, and the signs are colored according to the trail they are on. A description of the building the sign describes is on one side, and a map of Flushing showing the different hotspots is on the other.

Though Flushing has added hundreds of apartment buildings since the 1970s, and many more are under construction today, Cambridge Court, which has some medieval detailing including gargoyles, is one of a number found along Bowne Street that go back to the 1930s or earlier.

The first Flushing Freedom Trail, which was marked by a red line in the sidewalk and occasional small, red signs, was first proposed by Flushing High teacher and President of the Bowne House Historical Society Margaret Carman (1890-1976), a relative of Revolutionary War Captain “Lighthorse Harry” Lee and his son, Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Captain Lee described George Washington thusly in an address to the Continental Congress in 1793: “First in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Carman Green stands on triply historic territory. It borders both the Bowne House (the north side can be seen from the park) and also Kingsland Homestead, home to the Queens Historical Society but also a historic building in its own right, having been completed in Flushing in 1785. The green also stands on the site of Samuel Parsons’ plant nursery — Flushing’s history with the commercial plant industry began when William Prince established a commercial plant farm, or nursery, in western Flushing in 1737 along Flushing Bay. He first limited his business to apple, plum, pear and other fruit and flowering trees, and later expanded to shade and ornamental trees.

Other plant nurseries appeared in Flushing during the 1800s; one of the more successful was Samuel Parsons’, whose family gave Parsons Boulevard its name. Parsons brought the popular pink-flowered dogwood from Europe, as well as planted a weeping beech tree in 1847 on what is now 37th Avenue that survived 150 years. Its descendants, grown from cuttings, are still there.

A roughly triangular monument, commemorating what were the Fox Oaks, stands at the curb in front of Cambridge Court. As we’ve seen, Flushing’s history has always been closely intertwined with plants. The Quakers were no exception: a stone marker across Bowne street from John’s house, worn into a rough pyramid by time, reads: “Here stood the Fox Oaks, beneath whose branches George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends, preached June 7, 1672.” Bowne Street is still crowned by oaks.

A meeting for Quakers and their supporters at John Bowne’s place attracted so many people that Fox decided to hold the meeting outdoors at a pair of oaks at what was going to be Bowne Street in a couple of centuries. The oaks remained in place until 1863 when they were knocked down by lightning. The Flushing Historical Society placed the marker in 1907; a much larger Quaker Meetinghouse, still standing on Northern Boulevard, was opened in 1699.

Walking west along 37th Avenue, known as Washington Street when Flushing had more street names, another high-rise apartment house is going up. Flushing has already overtaxed its schools, water mains, transportation, and has precious little space left; but the developers, and the city goverment in league with them, keep building higher and higher, more and more.

The glut of signage and establishments crammed along Union Street is not to my taste, but I am from another time, another place. Union Street is one of those Flushing streets that changes character enormously from start to finish, so I devoted a whole FNY page to it.

Photo: Police NY

The practice of cramming names onto street signs makes them illegible from a distance. The Congressman Rosenthal on the 37th Avenue sign was Benjamin Stanley Rosenthal (June 8, 1923 – January 4, 1983), a Representative from New York, […] born in New York City. He attended public schools (including Stuyvesant High School), Long Island University, and City College. He served in the United States Army, 1943–1946, and received his LL.B. from Brooklyn Law School as well as an LL.M. from New York University, 1952. He was admitted to the New York bar in 1949 and commenced practice in New York City. He was elected as a Democrat to the Eighty-seventh United States Congress, by special election, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of United States Representative Lester Holtzman, and reelected to the eleven succeeding Congresses (February 20, 1962 – January 4, 1983). He died in Washington, D.C. wikipedia

He was succeeded by US Rep. Gary Ackerman, who served fifteen terms in the House from 1983-2013 and was succeeded by US Rep. Gregory Meeks.

Thomas Langone and Paul Tilty were NYPD Officers killed in the 9/11/01 terrorist massacre.

Continuing west on 37th avenue, the steeple of St. George Episcopal Church on Main Street comes into view across a massive parking lot. The parish has been in existence since 1702 and the current church building opened in 1854. Yet, the church doesn’t make the Top Five of the oldest buildings in Flushing! Its iconic steeple — a staple in postcard views of Flushing beginning in the 1800s — blew down in a tornado on September 16, 2010, but it was replaced with a new one three years later.

There was a building boom along Main Street between Northern Boulevard and the LIRR in the late 1920s and early 1930s. This Chase bank at 37th Avenue, with Deco elements, was built in 1929 (I don’t know what bank occupied it originally). Its clock no longer tells time accurately.

Pressing west on 37th Avenue, Citifield, the New York Mets’ third home field (after the Polo Grounds in Sugar Hill, Manhattan and Shea Stadium) comes into view. The park opened in April 2009 and currently (October 2015) is hosting its first postseason games.

The Mets, who first played in 1962, winning just 40 games, have always been referred to as playing in Flushing, but Citifield (and Shea Stadium) were west of the Flushing River, hence technically in Corona. Both parks were and are at the northern end of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, but originally the Flushing Meadows spread out on either side of Flushing Creek, until it was industrialized and turned into a “river” — technically it’s a creek.

Generations of Mets fans going to games at Shea could see this clock tower over the left center field fence, when it was the Serval Zipper factory. The building was actually built in the 1920s as the offices and factory for the W. & J. Sloane Furniture Company before it was a zipper factory. A couple of decades ago the zippers moved out and the building became a U-Haul service depot. Today, the hands on the clock seem to have disappeared. I hope they are replaced soon and the clock reactivated.

I have the full story at Brownstoner Queens.

A glimpse of the distant Shining City can be briefly vouchsafed from College Point Boulevard and 36th Road.

Turning right on 36th Road leads you into a confusing little maze of streets on which are located electrical supplies and lumber wholesalers, auto repair shops and chemical testing laboratories.

Meanwhile, the apartment towers necessary to house Flushing’s increasing population or visitors rise ever higher on nearby Prince Street.

The immediate area I’m walking in is shown on this 1909 map. All the small yellow boxes represent wood frame buildings, very few of which remain today. Note how close we are to the center of Flushing at the T-shaped intersection of Main Street and Northern Boulevard.

As I have mentioned, Washington Street is now 37th Avenue, while Sylvester Street is now 36th Road, Warren Street is 36th Avenue, while Hamilton Street is…

The unusually-named Bud Place, strangely named because there isn’t a plant in sight except for a few struggling street trees. Bud Place, though, is brimming with activity: importers; seafood wholesalers; heating, ventilating, and air conditioning dealers; construction firms; and indoor golf can be found along its short length.

As a look at a 1928 map, also in my collection confirms, the streets in the area had obtained their present names by then.

This is the last remaining wood frame dwelling remaining in the area, at Bud Place and 36th Avenue. You wonder what changes it has seen in its almost century-long tenure.

King Road is an unusually angled 2-block route running between College Point and Northern Boulevards. A look south provides a good look at the Zipper Tower, and if you’re lucky, you can also get a photo of a plane coming in for a landing at LaGuardia. Planes fly low over Flushing as they take off and land.

Why is King Road angled, though? The answer is simple. Take another look at the 1909 map and you will see railroad tracks in the place where King Road would eventually be. The street was created after the Whitestone Branch of the Long Island Rail Road closed in 1932 for a perceived lack of business. The LIRR actually offered to sell the line to the city, which would have made it a part of the Flushing Line subway, the present #7. The city did not want to shell out for the line, which traveled north into College Point and then swing east to Whitestone. In the 1950s, though, the Transit Authority did purchase the LIRR section bridged over Jamaica Bay to the Rockaways, and that is now part of the A train.

The Whitestone’s Flushing Bridge Street station was on Northern Boulevard just north of this location; Northern Boulevard was called Bridge Street as it went over the Flushing River, and Broadway east of that. As a legacy of this, though, we still have the Flushing Main Street station, so called to differentiate it from Flushing Bridge Street — and the name has never been changed…

Now, here’s a building I know nothing at all about and I’ve always been curious about. It’s a lengthy, rectangular-shaped building that takes up about the entire block between Northern Blvd., King Road, Prince street and 36th Avenue, it’s made of brick and has Dutch-style stepped gables and a central bell tower (the bell is still in place). This shot from the bridge gives you good idea of what the entire building looks like.

Most mysteriously, the building, which is home to a bait and tackle shop and a church among other things, says “Peter Haff Huis” on the central entrance, “huis” being Dutch for home. I’d have to say this was a restaurant or roadhouse along Northern Boulevard that would greet travelers after they had crossed the Flushing River Bridge, which has gone through much smaller iterations before the monster bridge of today.

The reliable Jason Antos, writing on the Queens Gazette, has the following:

“…One such building, which stands today, is the Peter Haff Huis (House) on the south side of Northern Boulevard. The building in a Dutch Colonial motif with a 235-foot frontage was designed by Edward Shepherd Hewitt and is home to a row of mom and pop businesses. Peter Haff was an early Dutch settler who built his home in Flushing around 1643 to 1645.”

Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church (now Queens Baptist Church), Prince Street between 36th Avenue and 36th Road, is one of the oldest African -American churches in New York City. It was founded in 1870, with the present building erected in 1919. The longtime pastor was Dr. Timothy P. Mitchell, who worked closely with Dr. Martin Luther King. He is remembered on the cornerstone of an adjoining newer church building and on a newly installed street sign.

10/18/15