When I last did a general walkabout in Woodhaven, it was all the way back in 2007, so there’s a little catching up to do. One of the more successful Forgotten NY tours was in this very neighborhood in June 2015, so I’ll use some of the notes from that day for this survey. I’ll repeat some material from my previous page as well as some new material I have discovered since then, and use all new photos for this page.

A little background:

Woodhaven and Ozone Park were settled in the 1600s by Dutch and English settlers, who gradually eased out Native Americans; Woodhaven became a racing hotbed in the 1820s when Union Course, at what is now Jamaica Avenue and Woodhaven Blvd. was built in 1820s. Centerville and Aqueduct Race Tracks would follow.

From the 1830s to the 1850s, what is now East New York and Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, and Woodville, Queens, were developed by Connecticut businessman John Pitkin. To avoid confusion by the Post Office with an upstate New York State town in the days before zip codes, Woodville residents voted to change Woodville’s name to Woodhaven in 1853.

Famous former residents of Woodhaven include: actor Adrien Brody (“The Pianist”), composer George Gershwin (“Porgy and Bess,” “Rhapsody in Blue”), pop star Brian Hyland (“Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini”), showman Danny Kaye (“Secret Life of Walter Mitty” and many others), and actor Barry Sullivan (“The Bad and the Beautiful”).

Two French immigrants, Charles Lalance and Florian Grosjean launched the village as a manufacturing community in 1863, by opening a tin factory and improving the process of tin stamping. As late as 1900, the surrounding area, however, was still primarily farmland, and from Atlantic Avenue one could see as far south as Jamaica Bay, site of present-day John F. Kennedy International Airport. Since 1894, Woodhaven’s local newspaper has been the Leader-Observer.

The former Cross Bay Theatre, 94-11 Rockaway Boulevard, at the junction of two of Queens’ busiest, pedal to the metal thoroughfares: Rockaway Boulevard, which connects Brooklyn with the Five Towns of Nassau County, and Woodhaven Boulevard, which roars from Queens Center on Queens Boulevard across Jamaica Bay to the peninsula. Here at Liberty Avenue at the border of Ozone Park, it changes monikers from Woodhaven to Cross Bay Boulevard.

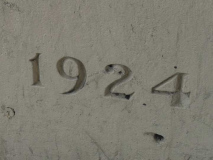

The theatre itself opened in December 1924 and remained open as a 3-screener until June 23, 2005. Like the Dyker on 86th Street in Bay Ridge, it became a Modells Sporting Goods store. One of the only relics of its time as a theater is the cornerstone reading 1924.

Attached houses on Woodhaven Boulevard north of Liberty Avenue. Note the intricate, two-toned brickwork. The porch is likely a later addition replacing an original.

You come to a fork in the road walking north on the east side of Woodhaven Boulevard. This is 95th Street, which takes an odd, crescent-shaped course from here at 103rd Avenue north to 95th Avenue.

It’s also the original course of the road that became Woodhaven Boulevard. This 1909 map (north is at left; I’ve added modern road names) shows what was called Woodhaven and earlier, one of the many roads in Queens named Flushing Avenue, snaking through the area. When the 8-lane Woodhaven Boulevard was laid out in the 1920s, it followed what was originally Walker Avenue, but the older road was left in place, and was renamed 95th Street when the streets were numbered during that decade.

Oddly enough, an area’s churches, liquor stores, beauty parlors, and drugstores preserve a neighborhood’s old character as well as any other institutions. Retail establishments emphasize the trendy and the new, making them less likely to retain any artifacts, or look the same as they did decades ago. Lacking a cornerstone, I don’t know the United Presbyterian Church of Ozone Park at 101st Avenue and 94th Street’s age, and like many churches and schools, it’s hard to find architectural information online.

Single and double houses dominate the side streets of Woodhaven, like this one at 95-20 93rd Street. That is likely the original porch, while the striped aluminum window shades give it an old-fashioned look.

One of the most impressive structures in Woodhaven is the Wyckoff Apartments. There are plenty of other buildings with ornate cupolas and towers in New York City, but this one seems all the more impressive because it is unique in Woodhaven…there’s no other building like it in the area. Its former Moorish-style conical dome, now sadly removed, made it a veritable skyscraper. The dome may have been removed, but there’s still enough detail on this 110-year old building to make it one of Woodhaven’s treasures; its cornices and eaves have not been lost to development. It was originally the home office for the Woodhaven Bank.

About a block away at Atlantic Avenue and 92nd street is another impressive relic, the clock tower of the offices of the old Lalance & Grosjean (pronounced Gro-zhan) manufacturing facility.

Just as piano manufacturer William Steinway built a small community to house his factory workers in northern Astoria, so did Lalance & Grosjean, the nationally renowned manufacturer that was among the first to make porcelain enamelware, a cheaper, lighter alternative to heavy cast-iron cookware under their brand name, “Agate Ware.” L&G set up business in 1863, and by 1876 had built a large kitchenware factory on Atlantic Avenue between today’s 89th to 92nd Streets, and workers’ housing on 95th and 97th Avenues between 85th and 86th Streets that remains there today.

The firm gradually expanded into a variety of products, including housewares, champagne, tinware, sheet metal and hardware. L&G became a nationally renowned manufacturer that was among the first to make porcelain enamelware, a cheaper, lighter alternative to heavy cast-iron cookware, under their brand name, “Agate Ware.” In addition to cookware L&G was one of the biggest names in tin stamping and license plate manufacturing. After sales declined in the 1950s, however, L&G went out of business.

In the 1980s, most of the Lalance & Grosjean red-brick factory buildings were razed in favor of a large Pathmark supermarket. In a similar situation to the Tower Square trolley barn at Northern Boulevard and Woodside Avenue, the clock tower, at the corner of Atlantic Avenue and 92nd Street, has somehow made it through the years, and is one of Queens’ best representatives of the form.

Several miles west on Atlantic Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, two cul-de-sacs, Alice and Agate Courts, were part of a real estate development by Florian Grosjean; he named them after his daughter, Alice Marie, and the agate ware on which he made his fortune.

The Woodhaven Cultural and Historical Society has erected a series of handsome blue and gold signs marking buildings of note in the area. They were modeled to resemble the metal signs placed by New York State in the 1930s marking such buildings. I have a series of the surviving and nonsurviving NYS signs on this FNY page.

Photographed just after Memorial Day 2015, the crosses and Stars of David symbolizing war casualties were an impressive sight in the Garden of Remembrance at American Legion Post #118 on 92nd Street and 89th Avenue. The post has been here since 1941.

I have a number of photos of St. Thomas The Apostle Church at 88th Avenue and 87th Street, as I was quite impressed with the architecture. St. Thomas’ handsome brick structure was erected in 1921 and features gorgeous colorful terra cotta banding and medallions. It was built to resemble a Bavarian country church, as in the early 20th Century most of its parishioners were German. Its onion spire can be recognized from several blocks away. The parish was founded in 1909 by Father Andrew Klarmann, whose name was appended to the adjoining parish center.

Some Catholic churches were wealthy enough to build the equivalent of small towns in addition to the churches proper. St. Thomas Church is accompanied by the priests’ and nuns’ residences as well as the Klarmann Memorial and the peaked and gabled Msgr. Chichester Center. One of the church’s former pastors, Fr. Joseph Martusciello, is remembered on a street sign at 88th Avenue and 88th Street. He was also a principal of my old high school, Cathedral Prep.

Angels’ faces peer out from the tops of columns at the Chichester Center entrance.

Jimmy Young Place remembers a local firefighter who died fighting a blaze in Manhattan in March 1994.

The corner of 87th and 88th doesn’t rate an actual stoplight, but an amber-flashing Cyclops has been installed on a telephone pole. A fire alarm and a now-nonfunctioning orange indicator lamp also are mounted on the pole.

In early 2015, an announcement was made about the closure of St. Luke’s Lutheran Church at 85th Street and 87th Road, and its congregation transferred, along with an other church, to a Brooklyn congregation. I do not know what will happen with this handsome blond-bricked church building, opened in 1910.

At the corner of 78th Street and 88th Avenue (formerly Snedeker, Snediker, or Sneideicker Avenue, depending on what map you consult, and 3rd Avenue), stands one of New York City’s oldest taverns, Neir’s, opened in 1855 (or 1829, depending on what account you read; the tavern itself says 1829) as The Pump Room, or Old Blue Pump House, to serve Union Course patrons.

The tavern stands just west of the grounds of the grounds of a former race track.

“The Union Course was the site of the first skinned — or dirt — racing surface, a curious novelty at the time. These courses were originally without grandstands. The custom of conducting a single, four-mile (race consisting of as many heats as were necessary to determine a winner, gave way to programs consisting of several races. Match races between horses from the South against those from the North drew crowds as high as 70,000. Several hotels (including the Snedeker Hotel and the Forschback Inn) were built in the area to accommodate the racing crowds.” wikipedia

Though Neir’s is one of the oldest drinking establishments in the city — even if it was founded in 1855, that puts it only a year or two younger than the purported age of McSorley’s in the East Village — it gets little notice or press outside of Queens. The founder was Cadwallader Colden, and that name might raise a scintilla of recognition for New York State history scholars: his great-grandfather, who had the same name, was acting governor of NY State and mayor of NYC in the colonial era. The Neir’s name comes from Louis Neir, who purchased the place in 1898, adding a bowling alley, ballroom, and rooms for rent upstairs.

Entertainer Mae West’s (1893-1980) name is attached to a number of institutions in Brooklyn, notably the Astral Apartments and Teddy’s in Greenpoint and North Williamsburg, and she is said to have begun her showbiz career singing here; a plaque marks her former home on 88th Street. At times, patrons say the ghost of Mae can sometimes still be seen here. Her association with Neir’s has been disputed, however. What is indisputable is that several scenes of Martin Scorsese’s mob epic Goodfellas, with Robert DeNiro and Ray Liotta, were filmed here, and scenes from other recent features as well.

Owner Loy Gordon and the staff welcomed FNY and friends warmly during a February 2015 presentation here, and also after the Woodhaven tour in June 2015. Personally, I’ve judged the burger as Queens’ best and perhaps NYC’s.

One day, I’ll get around to doing a feature about the neighborhood business district signs that have been installed all over town. This one appears on Jamaica Avenue in the 70s and 80s streets.

Vertical neon sign for a long-gone flower shop on Jamaica Avenue east of 80th Street. The florist is now one of two fingernail salons that are side by side.

An interesting small church, All Nations Baptist Church, at 80th Street and 87th Avenue. Services are in Spanish; the church was likely founded under a different name. The cornerstone notes the founding date of the original church (1897) and the construction of the present building (1910).

A historic sign placed by the Woodhaven Historical Society in a Compare Foods parking lot commemorates an earlier supermarket founded on this site by Fred Christ (pronounced “krist”) Trump, who developed affordable middle class housing in NYC, much of it in Coney Island, where Trump Village still carries his name. His son Donald, of course, needs no introduction.

Another supermarket parking lot (C-Town), another historic sign. Dexter Park began as a small sandlot-type field surrounded by playgrounds, bowling alleys, a carousel and a dance hall. Rosner founded the Bushwicks in 1913 and moved to Dexter Park in 1918, and it soon expanded to a 15,000-seat park with a steel and concrete grandstand. Rosner installed lights in 1930– a full five years before they arrived at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, and 8 years before Ebbets. Players from the AL, NL and the old Negro Leagues, some of which are named on the historic marker, played exhibition games against the Bushwicks after their regular seasons had ended, and Rosner signed Dazzy Vance and Waite Hoyt after their MLB careers ended.

After the 1940s, though, the arrival of television and the slow integration of the major leagues (decimating the Negro Leagues) took a toll on the Bushwicks’ attendance, and Rosner disbanded the team. After a few desultory years as a stock car venue, Dexter Park was razed in 1955, with two-family homes now occupying the site. The name “Dexter Court,” the sign, and the memories of players who are fewer in number as the years go by are all that’s left. Brooklyn regained pro baseball in 2000 with the arrival of the Brooklyn Cyclones, the Mets’ A affiliate, in Coney Island.

The parking lot has retained a single vintage lamppost with a fixture resembling the old Westinghouse OV20, but not quite the same; it could also be a Line Material Ovalite.

Rusty lamppost on Dexter Court. After a shaft reaches a certain level of rust, the NYC Department of Transportation no longer considers it effective to repaint it.

Briefly crossing the undefended border of Brooklyn and Queens, the former Franklin K. Lane High School’s tower looms over the former Brooklyn City Line. When built in 1923 and named for the Secretary of the Interior under President Woodrow Wilson, it was one of the largest high schools in the world. Over the decades it gained notoriety as one of the city’s toughest. After the graduating class of 2012 it was split into five separate schools: The Academy of Innovative Technology, The Brooklyn Lab School, Cypress Hill Prep Academy, The Urban Assembly School for Collaborative Healthcare, and Multicultural High School.

Among its alumni are Red Holzman, the only coach to pilot the New York Knicks to titles (1970, 1973) and actress Anne Jackson.

Heading east again at Jamaica Avenue the former offices of the Leader-Observer can be seen at #80-30. The newspaper was founded in 1909.

Forest Parkway

Forest Parkway, one of Queens’ best-kept architectural secrets, was developed as a showpiece of sorts as Woodhaven was being developed in the early 20th Century:

This, the only 80-foot wide residential street in Woodhaven, marked the center of the Forest Parkway development of 1900. Though only six blocks long, Forest Parkway was macadamized from the start, and big homes on 40-foot minimum lots were built to line itgs length. Many of these survive today as doctors’ and dentists’ offices. A few are still private residences. –Vincent Seyfried

The exterior of Woodhaven’s post office, built in 1940 on Forest Parkway just north of Jamaica Avenue, may look somewhat utilitarian and mundane, but it is a prime example of the streamlined Art Moderne style, with its enameled panels. A look inside will reward you with a view of a Works Progress Administration mural by Ben Shahn.

This building, 86-20 Forest Parkway, was the first building to be designated under the Queensmark program.

According to the NY Times, the program was begun by the Queens Historical Society in 1996. Designated members of the selection committee survey historic or architecturally interesting neighborhoods, seeking buildings worthy of recognition, and this building was the first chosen under its aegis. unfortunately, a Queensmark does not carry the official weight that a NYC Landmarks Commission designation does, so this building could be easily torn down if sold to a developer.

Another of Forest Parkway’s finest at 86-08.

Forest Parkway is also home to a couple of magnificent apartment complexes such as Forest Chateau at 85-50 across the street from the Woodhaven Library.

In 1901, the Scottish philanthopist/industrialist Andrew Carnegie Foundation gave $5.2 million to New York City for its libraries across the five boroughs. This started a remarkable project that would go on to build 1,680 Carnegie libraries across the United States and another 800 plus in Canada, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere in the world. In NYC, Carnegie gave to the boroughs according to population. Since Queens was the least populated borough at the time, they got the least amount of money. The Queens Library trustees were able to go to Carnegie himself and present a plan that gave them more money, enabling the library to build seven of the eight libraries planned for the borough.

Carnegie paid for the buildings, but the city would have to buy or acquire the land, buy the books, and provide for maintenance and upkeep, in perpetuity. Carnegie helped set up the library commissions and boards.

The Woodhaven branch of the QPL was the last building to be constructed under the Carnegie aegis, opening January 5, 1924. The architect was Robert F. Schirmer, who with J.W. Schmidt also designed the Library’s central building in 1927, which is now the Queens Family Courthouse (seen on this FNY page).

While her tree grew in Brooklyn, Betty Smith, neé Elisabeth Wehner (1896-1972), largely wrote the novel, which takes place in nearby Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, in this beautiful Colonial Revival house with a very unsual fence treatment at 85-34 on Forest Parkway near Jamaica Avenue. She herself lived in Williamsburg and attended Girls’ High School, where her childhood experiences influenced her book.

Before leaving Forest Parkway here’s a couple other of the street’s notable residences.

An actual New York State Education Department sign from 1936 was installed in front of this Queen Anne building at Park Lane South and 85th Street, not a new Woodhaven Historical Society sign. It doesn’t designate this building, however; it designates the first building in Queens to be numbered under the street and house numbering plan instituted by the Queens Topographical Bureau in the 1910s. The building stood on the opposite corner across 85th Street but has since been demolished.

Many years ago, when Queens was a collection of small towns divided by acres of farms and fields, every town and city had its own street naming and numbering system. This was all right when Queens (then also comprising what is now Nassau County) was a separate and self-governing county. Once Queens consolidated with New York City and subsequently became slowly urbanized, this was a situation that could not be allowed to stand as a plethora of Washington Streets, Main Streets, and 1st and 2nd Streets found themselves in the same street directory in the city ledgers.

And so, the Queens Topographical Bureau, under the guidance of C. U. Powell, was set the task of unifying Queens’ street system in the 1910s. To do this just about every street in Queens was assigned a number, except those in historic areas such as Flushing; some existing major roads kept their names, but were assigned the honorific Boulevard or Parkway to replace what was a mere Avenue or Road; the Jackson Avenue – Broadway combination was renamed Northern Boulevard, for example, while Little Neck Road became Little Neck Parkway. Numbered Avenues, Roads, Drives and Courts run east-west, while Streets, Places, Lanes and Terraces run north-south. Streets run from 1 to 271, and Avenues from 2 to 165: why Queens does not have a 1st Avenue is a mystery.

Queens also has a unique way of designating house numbers: the first one, two or three digits are the street number while the last two, separated with a hyphen, are numbered between that numbered street and the next. For example 95-01 would be at the corner of 95th Street while 95-35 would be at the corner of the next street, 96th, while the house numbers would begin anew with 96-01.

Forest Park

Though Queens has hundreds of acres of parkland, Forest, Kissena and Cunningham Parks usually take a backseat to Flushing Meadows Park, with its collection of corroding, deteriorating remnants of two World’s Fairs. Forest Park is up there among NYC’s biggest parks, with over 500 acres stretching between the cemetery belt, Kew Gardens, Union Turnpike and Glendale and Park Lane South in Woodhaven and Richmond Hill. It forms a natural boundary between communities in northern Queens (Glendale and Forest Hills) and their southern cousins. I confess to not having extensively explored Forest Park as much as I have, say, Central and Prospect Parks, and Forest Park makes no pretense of matching the cultural aspects of those two Olmsted and Vaux creations, though it has its moments.

Forest Park was actually created by the city of Brooklyn in 1895, with the city’s Parks Department buying up acres of forested, pretty much unused property, hence the name. It’s among the more ‘natural’ of our big parks, with about 165 acres left as woodland, interspersed with marked trails.

The park was surveyed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the co-developer of Central and Prospect Parks and much like the parks and natural reserves of Staten Island, Forest Park contains several nature trails ‘blazed’ or marked for the ease of hikers, and also boasts a bridle path.

I followed a park path from Park Lane South and 86th Street into the park, which quickly joins the vehicular Forest Park Drive, Coming into view almost immediately is…

The Seuffert Bandshell, named for George Seuffert, Sr., a popular musician and band leader, stands near the spot where he and his band first began offering Sunday afternoon concerts to the public in 1898. In 1928, Seuffert’s son, Dr. George Seuffert, took over and led hundreds of concerts featuring music by Wagner, John Philip Sousa, Cole Porter and many others. When he died in 1995 the Queens Symphony Orchestra took over the tradition of offering summer concerts there. Other nights have been added in recent years: kids events’ on Monday nights, rock on Thursdays and Fridays, and classical on Sundays. The bandshell was built in 1920 and renovated 80 years later.

Strack Pond, accessible from a short path to the right of the bandshell, was named for Pfc Laurence Strack, the first Woodhaven soldier killed in Vietnam. The Lindsay administration attempted to build some ballfields here in the 1960s, but the swampy ground would not cooperate, so at length, the Parks Department constructed a pond on the same site. While not a natural pond, it nevertheless provides a small area of peace and serenity in a busy part of the park.

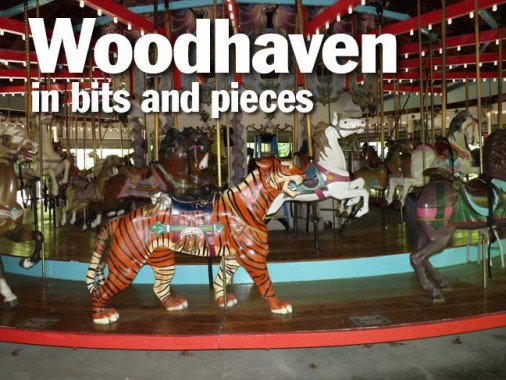

Every year, it seems, sees the closing of more of New York’s classic carousels, but Forest Park’s, just off Woodhaven Boulevard south of Myrtle, is still delighting kids big and small as it has since it was moved here from Dracut, Massachusetts, in 1971. This Daniel Muller carousel, built in 1903 and containing 54 wood horses and other animals, is one of just two remaining in the country. It replaced an earlier carousel that burnt down in 1966. The carousel contains 49 horses, a lion, a tiger, a deer, and two chariots arranged in three concentric circles. The carousel also contains an original carousel band organ. It’s a buck a ride for all ages.

Six other New York City parks operate carousels: Prospect Park in Brooklyn, Central Park and Bryant Park in Manhattan, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens, East River Park in DUMBO, and Willowbrook Park in Staten Island. The B&B Carousell in Coney Island, shuttered since 2003, reopened for business in 2014 on the boardwalk.

From here it’s a short walk to Woodhaven Boulevard for the Q53 or Q11 buses, or you can do what our Woodhaven tour did and walk back to Neir’s for a few beers and lunch.

11/8/15