By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten New York correspondent

Among the city streets that follow elevated subway lines today, none are completely in the shade. McDonald Avenue, New Utrecht Avenue, and Roosevelt Avenue all enjoy a few blocks in the open while having most of their routes hidden beneath the elevated tracks. Only Livonia Avenue in Brooklyn’s Brownsville and East New York neighborhoods is completely in the shade from beginning to end. Among the city’s elevated lines, the Livonia El is perhaps the least storied and least known on the account of its distance from Manhattan, and the historical stigma of the low-income areas along its route. Its stations are currently in the process of being renovated as neighborhoods along the way experience a boom in residential construction after decades of decline.

The line originally opened out to Pennsylvania Avenue on Christmas Eve 1920, and out to New Lots Avenue in October 1922.

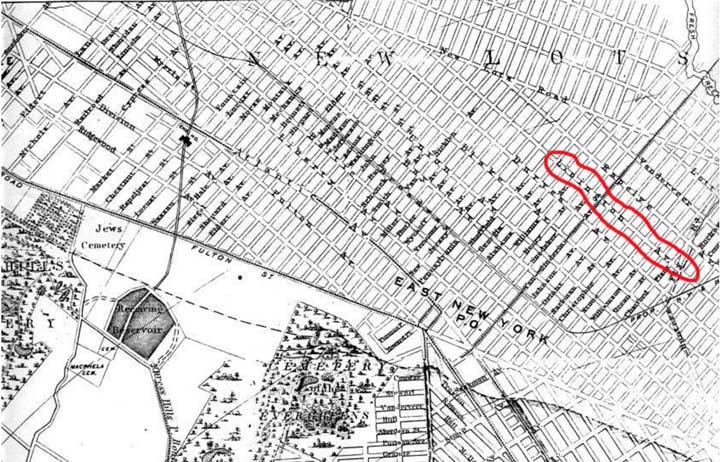

1874 map showing Linnington Avenue

During the Livonian Crusade (1193–1290) the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, known as the Livonian Order from 1237, colonized ancient Livonia. The name Livonia came to designate a much broader territory: Terra Mariana on the eastern coasts of the Baltic Sea, in the present-day northern part of Latvia and the southern part of Estonia. It bordered on the Gulf of Riga and the Gulf of Finland in the north-west, Lake Peipus and Russia to the east, and Lithuania to the south.

Livonia was inhabited by various Baltic and Finnic peoples, ruled from the 12th century by an upper class of Baltic Germans. Over the course of time, some nobles were Polonized into the Polish–Lithuanian nobility (szlachta) or became part of the Swedish nobility during the period of Swedish Livonia (1629–1721) or Russified into the Russian nobility (дворянство, dvoryanstvo). wikipedia

Brooklyn has its examples of functionally named streets. Force Tube Avenue in Cypress Hills comes to mind. On the border of Crown Heights and Brownsville, the IRT subway diverges from Eastern Parkway, emerging alongside the functionally named Portal Street. The portal is within the sizable Lincoln Terrace Park, which lies on the slope of the glacial terminal moraine. The park was co-named in 1932 for Arthur S. Somers (1866-1932), a local philanthropist and civic activist. To the south of this park, the terrain is a gently sloping coastal plain descending to the seashore.

Under East 98th Street

Crossing East New York Avenue, the tracks follow East 98th Street in a southeast direction for a half mile. This road and nine others to its west are an extension of the Canarsie street grid that pierces into the larger Brooklyn grid. As a borderline between the two grids, East 98th Street is where many of Brooklyn’s east-west streets end, such as Church Avenue, Sutter Avenue, and Livonia Avenue. The great Kings highway also has its eastern end at East 98th Street. Sutter Avenue-Rutland Road is the only station on the Livonia El that is not on Livonia Avenue, serving commuters living in this nine-block grid.

Jewish Streets

In the first half of the 20th century, Brownsville and East New York were overwhelmingly Jewish, populated by refugees fleeing persecution and poverty in Eastern Europe. A pattern emerged where Jewish immigrants first lived on the Lower East Side and then moved either uptown to Harlem and the Grand Concourse, or east to what was then the edge of the city in Brownsville. Very quickly the neighborhood became as dense as the Lower East Side, with pushcart vendors, mobsters (Midnight Rose, an all-night candy store on Livonia, became headquarters for Murder, Inc.), Hebrew schools, and synagogues in the mix. In 1913, residents of Brownsville petitioned to have Ames Street renamed after Theodor Herzl a decade after his death. The Austrian-born journalist founded the Zionist Congress in 1897, which led the effort towards the creation of modern Israel.

A block away, Douglass Street became Strauss Street, in honor of the philanthropic brothers Nathan and Isidor Strauss, who owned the Macy’s department store. A former Congressman, Isidor went down in history aboard the Titanic, where his wife Ida gave up her lifeboat seat to a younger passenger. Not far from them is Zion Square on Pitkin Avenue and Legion Street (2nd photo), where the monument features a Star of David.

No Jews reside on Herzl Street today but many local churches still retain architectural elements that remind us of their past use as synagogues.

I thought that this was the only Herzl Street outside of Israel. Actually, there’s another one in Memphis and a recently built Herzl Street in in the Toronto suburb of Kleinburg.

Up above in the Saratoga Avenue el station, we find an original 1920 exit sign. Look at the craftsmanship, the serif lettering, the rendering of the arrow on this beautiful navy blue and white sign. (Not sure it’s still there, as this comes from a 2009 photo on nycsubway.org.)

We can only hope that when the Metropolitan Transit Authority, which has now been alerted to the presence of this nonstandard sign, removes it, it could be donated to the Transit Museum instead of it taking its place in a landfill or on a private collector’s wall.

Betsy Head Park

This two block park, on the north side of Livonia between Strauss and Thomas S. Boyland Streets, has been a curiosity on the account of its name. According to the Parks website, Betsy Head was a British-born philanthropist who bequeathed funds of the establishment of this park in 1914. The pool was originally built in 1915 and expanded as a public works project in 1936, incorporating elements of the Art Moderne style in its design. This includes the parasol roof that today is closed to the public.

A block to the north of the pool is a smaller portion of Betsy Head Park where the playground received an ambitious redesign in early 2016. Billed as the Imagination Playground, it features an elevated walkway ringing the play area. It is reminiscent of the nearby elevated subway but actually inspired by treehouses.

Hopkinson to Boyland, Stone to Gaston

The street running past the pool is Thomas S. Boyland Street, or Hopkinson Avenue as it was known to older Brownsville residents. Born in Memphis, he was elected as the State Assemblyman for the neighborhood in 1977. A former math teacher whose previous career included time spent teaching in Zambia, Boyland lived in a time of civil rights activism and increased identity awareness among African-Americans. His three sons were named Djanja, Shaka, and Jumaane. Boyland died at the young age of 39 in 1983 and was succeeded by his brother William F. Boyland, who in turn was succeeded by William Boyland Jr. The third office-holding Boyland tarnished the family name in 2014, convicted of bribery and removed from office. The neighborhood dynasty was described in a 2005 New York Times article as the “Kennedys of Brownsville.”

Prior to carrying Boyland’s name, this road was called Hopkinson Avenue, which honored Francis Hopkinson (1737-1791), a signer of the Declaration of Independence from New Jersey. Scholars say he played a substantial role designing the American flag and national seal. He also wrote essays, played the harpsichord and the organ. He was among the 41 slaveholding signers out the 58 in total.

As Strauss and Herzl memorialize Brownsville’s past as a Jewish neighborhood, local black history is on the map with Boyland and nearby Mother Gaston Boulevard. The reason for Stone Avenue’s renaming can be found at the Gothic revival library on the corner of Mother Gaston Boulevard and Dumont Avenue (shown above). It was here that local resident Rosetta Gaston (1895-1981) founded the Brownsville Heritage House, promoting history and culture. Shortly after her death, the avenue passing by the library was assigned her name.

Related: Still Stone-d in Bedford-Stuyvesant

Housing Projects

To the east of Rockaway Avenue, the elevated line runs past a series of public housing projects: Brownsville, Van Dyke and Tilden. When the Brownsville houses were built, they stood in a racially and economically mixed neighborhood. Within a decade, redlining, public disinvestment, white flight and crime had completely changed the neighborhood. In those years, more projects were built, completing the transformation of Brownsville into the lowest-income section of Brooklyn. One can imagine taking a graffiti-covered 3 train in the 1980s past these projects. Rivaling the South Bronx, this is the New York that tourists feared.

My first encounter with these projects was in November 2008, when I reported on the murder of Imonil Aminov, a Bukharian Jew who was delivering meals to homebound seniors living in these projects. “No snitching” was the rule on these streets and to this day Aminov’s murder is unsolved. I attended his funeral and mourned with his family.

I presume that these projects are safer today than in 2008, but nevertheless the place sends chills when I pass them by. A murderer lives here.

Livonia Park

At Powell Street is a sitting area, Livonia Park, where I sat to take a break on this photo essay. All along I wondered why there is an avenue in Brooklyn named after a historical Baltic province. For those unfamiliar with its history, Livonia was located in what are now Latvia and Estonia, named after its indigenous residents, the Liv people. It was never an independent state, ruled by the Teutonic Knights, Sweden, and the Russian Empire. For eight brief years Livonia was a nominally impendent puppet state of Ivan the Terrible’s Russia. But when its Danish-born King Magnus lost the tsar’s favor in 1578, so did the kingdom’s brief moment as a sovereign state.

Over the centuries the Liv were subject to persecution and gradually assimilated into the larger Latvian people. Like the Celts of the British Isles, unassimilated Livs were pushed to the edge of the sea. Today, the last redoubt of Livonian culture and language is at Cape Kolka, a spit of land where the Gulf of Riga and Baltic Sea meet.

Livonia Park was developed together with Tilden Houses in the 1960s. To give the park’s name meaning, it is decorated with red and white paving bricks evoking the Latvian flag.

While it is accurate as most of Livonia is within today’s Latvia, the Liv people have their own flag, a green-white-blue tricolor. If it were up to me, I would have the flags of Latvia, and Livonia displayed together at this park, alongside the standard Parks flagpole.

My connection to Livonia is that I was born in Riga, Latvia. I’ve always wondered why is there an avenue relating to my birthplace in this largely African-American neighborhood.

Junius Connection

Above Livonia Park is the Junius Street station, where the elevated structure rises higher to cross over the LIRR Bay Ridge branch and the Canarsie (L subway) line. Being only a block away from the L train’s Livonia Avenue station, it is odd that the two were never given a transfer connection. Certainly these stations don’t see as much foot traffic as other stations that cross each other, and the estimated number of transfers wouldn’t be that high, but in a neighborhood that has been historically underserved by public services, wouldn’t a free transfer improve commutes by adding an extra option? There is talk of enabling a walking free transfer similar to 63rd Street-Lexington Avenue, with the eventual construction of a transfer passageway.

Alongside the Canarsie Line, the LIRR Bay Ridge branch hasn’t seen passenger service since 1924. There is talk of transforming it into an outer-borough Triboro RX line, but here the MTA has not committed to it. Another plan proposes expanding its use as a freight line with a Cross Harbor Tunnel from Brooklyn to Bayonne. For now, this line is quiet for most of the time.

[ed.: the connection is now likely to be made due to the upcoming L line shutdown for Sandy-related track repair beginning in 2019]

Livonia Commons

Seeking to balance the demand for residential construction while keeping it affordable, the city approved in 2012 a set of buildings along Livonia Avenue between Van Sinderen Avenue and Pennsylvania Avenue that includes a senior center, community center, school and garden. The architecture of Livonia Commons is postmodern, incorporating bright colors into the design as opposed to the uninspiring brick boxes of the nearby housing projects.

Fortunoff’s in East New York

On Pennsylvania Avenue just north of Livonia is a fading painted ad mural promoting Fortunoff’s department store in East New York. It sounds absurd, perhaps, to see such an upscale brand in this ‘hood. Its story began in 1922 when Max and Clara Fortunoff opened a household goods store on Livonia Avenue under the tracks. As the company grew, it expanded to selling jewelry and other fine items.

In 1964, the Fortunoffs followed their customers to the suburbs, closing their East New York store and reopening it in Westbury. Its grand department store survived until 2009. The company reorganized to sell many of its items online and later opening separate outdoor furniture and jewelry stores under the family name.

Wyckoff Triangle

Digressing a bit away from Livonia Avenue, there is a small triangular park at New Lots Avenue, Riverdale Avenue and Van Siclen Avenue. Titled Wyckoff Triangle, it honors the memory of Hendrick Wyckoff, a descendant of Dutch settlers whose property covered this triangle and the lbock to its immediate north. During the American Revolution, Wyckoff sneaked into British-occupied Brooklyn to collect information and funds for the patriots. His descendants maintained the property into the 1920s, when it was sold and subdivided by the street grid. This triangle is a remnant of Wyckoff’s estate, too small to be developed and designated as a public park.

East New York Farms

One benefit of the urban decay that took place between the 1960s and 1980s is the opening up of vacant land throughout the inner city, with some of it transformed into parks and community gardens. East New York Farms is among the larger gardens, maintaining its own farmers market in view of the elevated tracks.

More in FNY: East New York Community Gardens

New Lots Reformed Church

In the colonial period, each of the borough’s original towns had its own parish of the Dutch Reformed Church. The one in Flatbush relates to Church Avenue, which runs past it. In 1821, the farmers of New Lots felt that the ride to Flatbush was too far and established their own local Reformed Church next to the town’s cemetery. The craftsmanship and federal style of this church earned it a city landmarks designation in 1966.

Its cemetery includes the graves of American revolutionaries and slaves, as well as namesakes of local streets such as Van Siclen, Schenck, Van Sinderen and Remsen, and the Rapaljes (who re remembered by Rapelye Street in Carroll Gardens).

African Burial Ground

Across the street from the historic church is the New Lots branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, a simple modernist facility completed in 1957. Before entering the library, I noticed street signs designating the block as African Burial Ground Square. I thought of the African Burial Ground in Manhattan and then remembered that prior to the revolution, New York had the largest population of slaves outside of the South and many worked on the farms in Kings County. In October 2013, the former cemetery site was designated as African Burial Ground Square with plans in the works to give Schenck Playground behind the library an African-themed redesign and a new name.

New Lots Avenue Station

In 1922, the IRT Lexington Avenue / Seventh Avenue lines reached their easternmost point in Brooklyn at this station. The terminal is unique in the IRT system as the only one without bumper blocks, with tracks continuing beyond into the yard with possibilities of extending train service further east.

At this point, Livonia Avenue reaches its eastern tip, making a triangular intersection with the grid-defying New Lots Avenue. The city DOT extended this triangle into a pedestrian plaza, beautifying an otherwise mediocre conclusion to the 3 train.

Livonia Yard

A couple of blocks to the south of New Lots Avenue, the el widens into Livonia Yard, a storage complex for the 3 train. The yard straddles the pedal-to-the-metal Linden Boulevard, with its bumper blocks at Sutter Avenue. The blocks around this yard are industrial, mostly warehouses and small workshops. Occasionally, there is talk of extending revenue subway service into the yard with a new station at Linden Boulevard. There is precedent for this at the northern end of the 3 train. In 1968, the 148th Street-Lenox Terminal station was carved out of the Lenox Yard in Harlem, offering residents of that neighborhood an extra subway station and making the walk to the train shorter for many commuters.

Beyond New Lots

Why terminate the line at Livonia Yard when the recently built Gateway Center mall and Gateway Estates development are only three blocks to the south? Back in 1968, nearly four decades before Gateway Center Mall was built, the city had plans to extend the line to Flatlands Avenue ahead of the area’s development. The city’s financial crisis in the following decade put a halt to the plan.

Those three blocks are mainly industrial so there would be no opposition here towards extending an elevated line here. An extension to Gateway will connect its residents to the subway, transit-riding public to its mall, and the soon to open park atop the former Fountain Avenue landfill that faces Jamaica Bay.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (Countryman Press, 2016)

9/4/16