Continuing my recent spate of stories about what the streets underneath elevated lines look like (Livonia Avenue, New Utrecht Avenue) I decided to head to an area I have appreciated for some time, downtown Richmond Hill at Jamaica Avenue and Lefferts Boulevard. There’s a healthy concentration of Forgotten New York – type artifacts concentrated in a 5-block radius, making it fair game for tours (I have led two here in 2014 and 2016).

There is also a stretch of the Long Island Rail Road placed on an elevated trestle. These tracks last saw passenger service approximately 10 years ago and the elevated Richmond Hill Station accepted its final passenger in March 1998. However, freights still use these tracks. It’s unusual for the LIRR to run on elevated tracks in NYC; the longest two stretches are on Atlantic Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

Railroad builders would much rather trains not tackle high hills if it can be avoided, and so railroads are placed in tunnels, open-cut trenches, at grade, on embankments, or on elevated trestles depending on topography. On Atlantic Avenue, the grade surface rises and falls, but the railroad is kept on a straight line alternately in tunnels or on els. The same happened in Richmond Hill, as the tracks emerge from hilly Forest Park into the valley of Richmond Hill. To keep the trains on a relatively straight grade, they were placed on an elevated structure.

Alighting from the Jamaica el at 121st Street I headed west toward the LIRR trestle. I’d have to guess that it predates the Jamaica el, since the latter was built very high, to rise high above it. This is one of three occasions in Queens in which elevated subway trains and Long Island Rail Road trains cross each other; the other one is at Woodside, which is a major interchange for the LIRR Main Line and Port Washington Branch, as well as the #7 Flushing IRT el. (Another is where the defunct Rockaway Branch crosses the A train el on Liberty Avenue.)

Not long ago I floated the idea that this crossing in Richmond Hill could also be made into a major transit interchange if passenger service on the LIRR here could be reactivated. This idea was shot down by a number of rail experts and fans, the main complaint being that it is too close to the Jamaica Avenue LIRR station, which is a major interchange for all lines that branch from the Main Line. It is also served by subways serving the IND/BMT E and J lines.

This is the now-shuttered entrance to the Richmond Hill elevated LIRR station. It would’ve been hard to connect it to the J train 121st Street station a block away, but it my “idea” had been pursued, the J station could have been moved a block west to Lefferts.

I’ll deal with the Richmond Hill station a bit more later on, but here it is during a Long Island Rail Road fantrip in September 1999, about 18 months after it was closed to the public and passenger service ended on the line in March 1998. The steps have since been removed, preventing anyone scuttling about with a camera from possibly attaining the platform.

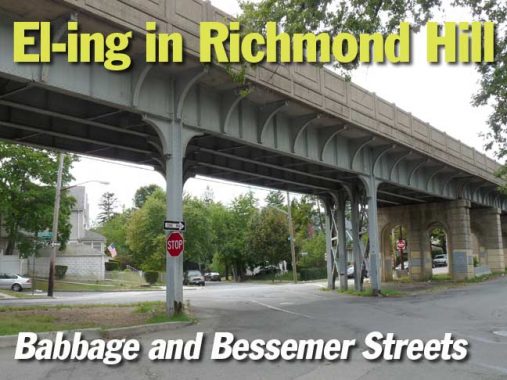

There are two streets that run alongside the elevated LIRR trestle between 84th Avenue and Lefferts Boulevard. They appear on maps in 1909 and seem to have attained their names by the 1920s. The street on the east side of the railroad is named Babbage Street and the street on the west side is named Bessemer. The reasons for these names is uncertain, but perhaps I’ve found an answer. (The Brendan Byrne on the sign is not the New Jersey governor, but rather honors a local luminary.)

New York City, at one time or another, has had three settlements named Richmond Hill. The one in Manhattan, in what is now the west Village, and the one in Staten Island, in what is now Richmondtown, have pretty much been absorbed into new neighborhoods. Queens’ Richmond Hill has been more enduring. In 1869, developers Albon Platt Man and Edward Richmond laid out a new community just west of Jamaica with a post office and railroad station, and Richmond named the area for himself (or, perhaps, a London suburb, Richmond-On-Thames, a favorite royal stomping ground). It became a self-contained community of Queen Anne architecture west of Van Wyck Boulevard (now Expressway) that remains fairly intact to the present day. Journalist/activist Jacob Riis as well as the Marx Brothers were Richmond Hill residents in the early 20th Century.

Thus, Richmond Hill may well have been considered to have very much of a British flavor by the developers. When two streets laid out by the el trestle needed names, they were given two names of Britishers who were very much involved in science and industry.

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (1791-1871) was a mechanical engineer and mathematician. Along with Ada Lovelace, Babbage is considered by some to be a parent of the modern computer.

Babbage began in 1822 with what he called the difference engine, made to compute values of polynomial functions. It was created to calculate a series of values automatically. By using the method of finite differences, it was possible to avoid the need for multiplication and division.

For a prototype difference engine, Babbage brought in Joseph Clement to implement the design, in 1823. Clement worked to high standards, but his machine tools were particularly elaborate. Under the standard terms of business of the time, he could charge for their construction, and would also own them. He and Babbage fell out over costs around 1831.

Some parts of the prototype survive in the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. This prototype evolved into the “first difference engine.” It remained unfinished and the finished portion is located at the Science Museum in London. This first difference engine would have been composed of around 25,000 parts, weigh fifteen tons (13,600 kg), and would have been 8 ft (2.4 m) tall. Although Babbage received ample funding for the project, it was never completed. He later (1847–1849) produced detailed drawings for an improved version,”Difference Engine No. 2″, but did not receive funding from the British government. His design was finally constructed in 1989–1991, using his plans and 19th century manufacturing tolerances. It performed its first calculation at the Science Museum, London, returning results to 31 digits.

Nine years later, the Science Museum completed the printer Babbage had designed for the difference engine. wikipedia

Henry Bessemer

Henry Bessemer (1813-1898) developed the Bessemer process for mass-producing steel.

Bessemer worked on the problem of manufacturing cheap steel for ordnance production from 1850 to 1855 when he patented his method. On 24 August 1856 Bessemer first described the process to a meeting of the British Association in Cheltenham which he titled “The Manufacture of Iron Without Fuel.” It was published in full in The Times. The Bessemer process involved using oxygen in air blown through molten pig iron to burn off the impurities and thus create steel. wikipedia

At Hillside Avenue, a major route to the middle of Nassau County, the trestle was given a grand concrete bridge, and inscribed on each side is a keystone symbol.

The LIRR was run under the auspices of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1900 to 1949, and in those years, the LIRR signage adopted the “Pennsy” keystone symbol, since Pennsylvania is called the Keystone State. Until 1955, the LIRR’s chuffing steam engines all carried a keystone plate on their noses, when the last steam engine was retired from active service. One of their complement, Steam Engine #39, is exhibited, Pennsy plate included, at the Railroad Museum of Long Island in Riverhead.

Surprisingly, few Pennsylvania Railroad relics, aside from the name of the main terminal in New York City, remain from the LIRR’s Pennsy days; this is one of the few.

The Richmond Hill public library was built in 1905 by the architectural firm Tuthill and Higgins with a grant from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie on land donated by Albon Man, the founder of Richmond Hill. Inside is a large mural painted in 1936 by artist Philip Evergood showing Richmond Hill as a suburban alternative to the hustle and bustle of the big city.

Across Lefferts Boulevard from the library is the landmarked Republican Club building that, thanks to a recent rehabilitation, pretty much looks the same on the exterior as it was when it was built in a Colonial Revival style by architect Henry Haugaard in 1908. Now a catering hall, the building hosted Republican Party meetings and has been visited by Calvin Coolidge, Warren Harding, Theodore Roosevelt, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan and even Democrat Harry S Truman. The club remained an important gathering place for the Republican Party throughout the 20th Century well into the 1980s.

The rain shelter for the Richmond Hill elevated station remains readily visible from the street…

The last time a large group of people were milling about on the elevated station was during the LIRR fantrip in September 1999. The MP-72 unit was typical of the train cars that would stop at this station in its final days.

I last took the train that ran along the “Montauk branch” that had stops in Richmond Hill, Glendale, Fresh Pond Road, Haberman (named for a local business in Laurel Hill), Penny Bridge (named for the Kosciuszko Bridge’s predecessor), and Long Island City when it was still using all these stops in 1998. I was fascinated: the stops, for the most part, were nothing more than clearings along the tracks; Richmond Hill was the only one with a sign. There were only about 4 daily runs, two in the morning and two in the evening. People waved at the train as it went by, as they would in rural regions in the south and west. The ride cost over $4 at a time when local runs elsewhere in Queens cost $2.50.

Finally the MTA ceased intermediate stops along the line because new cars with steps made for high level platforms were coming in. The Montauk soldiered on with express runs from LIC to Jamaica for awhile, but they ceased too.

I always mourn the end of local train service; I feel it’s a lot of potential wasted and if the MTA wanted to upgrade the tracks and build real stations, not only here but on the Rockaway and Bay Ridge branches, those routes could make money. But I am a railfan.

There are some relics along this stretch of Babbage Street; at 118th Street there are a pair of battered pay phones. These are largely used as garbage receptacles these days along with decommissioned fire alarms.

A handsome weeping willow tree stands at Babbage and 117th Street.

What has fascinated me about the LIRR trestle here since I started riding my bicycle into the neighborhood after moving to Queens in 1993 is the near perfect perspective provided by the concrete arches. It’s not lengthy enough for a vanishing point but it would have one if it were.

The LIRR elevated crosses three avenues in this stretch and all three of the trestles are different. This one is at 85th Avenue and is pretty much a continuation of the trestle between blocks; compare to the concrete canopies it was given at Hillside Avenue.

Jacob Riis Triangle, 85th Avenue at Babbage and 116th Streets.

Jacob August Riis (May 3, 1849 – May 26, 1914) was a Danish American social reformer, “muckraking” journalist and social documentary photographer. He is known for using his photographic and journalistic talents to help the impoverished in New York City; those New Yorkers were the subject of most of his prolific writings and photography. He endorsed the implementation of “model tenements” in New York with the help of humanitarian Lawrence Veiller. Additionally, as one of the most famous proponents of the newly practicable casual photography, he is considered one of the fathers of photography due to his very early adoption of flash photography. While living in New York, Riis experienced poverty and became a police reporter writing about the quality of life in the slums. He attempted to alleviate the bad living conditions of poor people by exposing their living conditions to the middle and upper classes. wikipedia

Riis, a Richmond Hill resident for a time, was a congregant at the historic Church of the Resurrection on 118th Street. His house in the neighborhood has since been demolished.

I have had to reference a number of sources for this little page. Among them was the Handbook of New York City Street and Park Lighting Equipment, issued by the Welsbach Corporation in 1963. Of course, I recognized this fixture, but had hardly expected to find it illuminating a backyard path.

It is, of course, the 3438-1. This unit appeared frequently in outlying parts of the city beginning in the 1940s and was the predecessor of the somewhat lookalike Westinghouse AK-10 “cuplight” units. The “cuplights” were a little smaller and had glass diffuser covers.

This is not the last time on this walk I would encounter the 3428-1! I will explain later.

The triangular plots caused by the RR’s diagonal path make for some spacious backyards.

The tastes of some local homeowners eludes me. Here, a house is completely enveloped in stucco and every vestige of green has been expunged from the front lawn.

The trestle looks shorter than 13’5″, but that’s enough to fit most trucks under.

A collection of nicer homes, and considerably more green, along Babbage Street between 84th and 85th Avenues.

Clearance is reduced to 10″2″ above 84th Avenue. One avenue remains north of here and below Forest Park, Park Lane South, but there, the Montauk Branch runs in an open cut and Park Lane South is bridged over it.

A pair of eclectic homes, one of them stucco-ized, along the hillside on 84th Avenue at Bessemer Street.

Looking south along Bessemer from 84th Avenue, which is sidewalk-free in spots, making it seem a bit more suburban.

On my last few visits to Richmond Hill I’ve seen this Cadillac ambulance parked on 85th Avenue and 114th, a block away from the LIRR. It appears to be from 1974. The Ghostbusters ambulance was from a few years earlier.

A porched house with a wide driveway on Bessemer Street.

Before leaving the LIRR elevated, I can’t resist a couple shots I got, risking getting splattered with pigeon poop (the architects of the concrete arch didn’t take that into consideration) of a couple more 3438-1 units hanging under the trestle (you never know what you’ll find under elevateds). These are corroded through in some spots, but both still have their incandescent bulbs and could presumably be turned back on again.

This building at Bessemer Street and Hillside Avenue looks much as it did in the 1920s on the 2nd and 3rd floors…

Here is the same building in the 1920s, when there was a tire store on the corner and a Bohack’s next door with Thanksgiving turkeys hanging in the window.

German immigrant Henry C. Bohack opened his first grocery in 1887 and over the years Bohack’s developed into one of the first powerhouse grocery store chains. Grand Union, Key Food and all the rest were to follow. When the Depression arrived in late 1929, Bohack responded by actually opening more stores to provide employment. The founder passed away in 1930. Bohack’s prospered until 1974 when the chain went bankrupt. After an attempted merger with Shoprite failed, Bohacks disappeared into the history books in 1977. Occasionally, though, an old awning or sign is taken down and the Big B is in evidence briefly once more.

This image, by the way, and many more like it, are available in Forgotten Queens by me and the Greater Astoria Historical Society.

Next door to the old Bohack’s, Richmond Hill preserves its very own classic movie palace of yore… and this one has a marquee that has been returned to its look in its halcyon days, with red neon-lit nameplates and a gold border. The theatre opened as the Keith’s Richmond Hill about 1928 at 117-09 Hillside Avenue just east of Myrtle Avenue. The old marquee, which had been hidden under aluminum siding for some years, was restored in 2001 during production for a feature film, “The Guru.” Until the 1960s, it also hosted stage shows; England’s Dave Clark Five appeared there at the height of their popularity in 1965. Unfortunately the years have not been kind to its ornately constructed interior, though it’s structurally sound.

On this occasion I was able to get a couple of shots of the entranceway before being shooed away by one of the employees, complaining that it’s “private property.”

He’s just doing his job so I duly obeyed, but what is the problem with taking photos of private property? Nearly every photo in Forgotten New York depicts something that is private property. If you’re a property owner who thinks this way and doesn’t mind your remarks being shown here, email me at kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com.

A couple of doors from the RKO, the Karnival nightclub was the location of one of the last Jahn’s ice cream shoppes left standing.

Jahn’s once covered the NYC metropolitan area with a heady combination of lactose and sucrose. The first Jahn’s was opened way back in 1897 in Mott Haven, Bronx by John Jahn, which (disappointingly) is pronounced “John JAN.” His three children, Elsie, Frank and Howard, opened Jahn’s in Jamaica, Richmond Hill, and Flushing respectively.

Jahn’s is most celebrated for its Kitchen Sink sundae, which was large enough to serve six. There were also the Boilermaker, the Awful Awful, the Suicide Frappe, Screwball’s Delight, the Joe Sent Me, and the Flaming Desire, five scoops of ice cream topped by a flaming sugar cube.

The Jahn’s at Richmond Hill, on Hillside Avenue just north of Myrtle, opened a short time after the RKO Keith’s theatre opened in 1929. It closed Thanksgiving weekend 2007. The only remaining Jahn’s is on 37th Avenue in Jackson Heights.

Forgotten Fan John Cullinan squeezed off some pictures before the closure.

A look west on Myrtle Avenue, which extends west several miles to downtown Brooklyn, as well as a couple miles east to Jamaica Avenue. It was built as a plank road in the 1850s.

FNY has walked its entire length.

Bangert’s Flowers, on 117th Street south of Myrtle, has lost some of its iconic exterior signage which likely dates back to the store’s opening in the 1920s, but the old FTD logo can be found on the inside. Some ancient checkerboard tilework remains too.

The flower shop is positively ancient: it started out as Fluhr’s in 1894 and was sold to the Bangert family in 1927.

Here’s a Beaux Arts apartment building on the corner of Jamaica Avenue and 117th that has it all architecturally, down to the reclining cherub above the entranceway. The architect’s name is lost to time, or at least to immediate access. It was likely built before 1910.

I’ll be in Richmond Hill again before too long but before kicking it in the head for this post, how about a couple more abandoned signs and an outmoded lamppost design under another el.

Founded in 1907 by the National Lead Company, Dutch Boy is currently a subsidiary of, and is owned and operated by the Diversified Brands Division of the Sherwin-Williams Company, who acquired it in 1980.

The Dutch Boy symbol was painted by Lawrence Carmichael Earle and modeled after an Irish-American boy who lived near the artist. wikipedia

This was a lamppost design that was featured under elevated trains in the 1970s and 1980s, but has since been replaced by other designs, mostly New Gumballs on L-shaped posts. There are still a couple remaining like this one on Jamaica Avenue. I’ve spotted others on Roosevelt Avenue and Northern Boulevard.

10/2/16