It was a gorgeous day when I did a reconnaissance walk for a since-completed Forgotten NY tour of Uptown Trinity Cemetery. So much so that when I was finished, I kept right on going and crossed over into the Bronx, where I walked past the New Yankee Stadium (where I still have not seen a game, though I did tour it on a n off-day when it first opened) and on to the Grand Concourse, where I got a D train back to Manhattan.

As it turns out, the day of the tour was overcast with drizzle and light rain, so the cemetery looked a lot better the day of my scouting mission than it looked the day of the tour, and thus, I’ll show a bit of that today as well as some of my other discoveries…

GOOGLE MAP: UPTOWN TRINITY CEMETERY TO YANKEE STADIUM

To get to Uptown Trinity Cemetery I took the #1 train to 157th Street and walked two blocks south on Broadway. Opened on November 12, 1904, it was the first new station opened by Interborough Rapid Transit after the Original 28 Stations opened on October 27th of that year. 157th Street closely resembles its preceding station, 145th Street, with large mosaic identifying tablets and terra-cotta “157” cartouches at the roofline. When the IRT began using longer trainsets, it was necessary to extend the platforms, and these extensions are plainly visible as mosaic “157s” are used instead of the cartouches, and serifed “157th St.” lettering was done instead of new mosaic tablets.

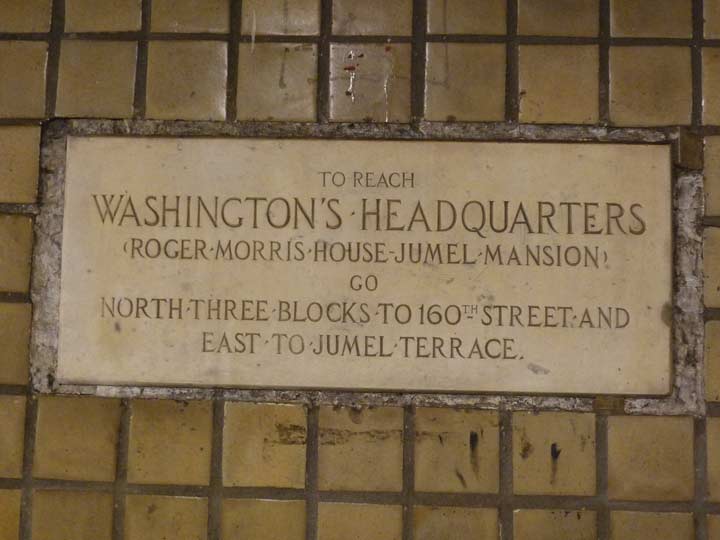

This tablet was placed at the 157th Street station relatively early on. It refers to the Morris-Jumel Mansion at Roger Morris Park, Edgecombe Avenue and West 162nd Street, about 5 blocks away from the station. The 163rd Street-Amsterdam Avenue station serving the C train is much closer to the Mansion, but it didn’t open until 1932.

Plenty of postcard scenes, and historic plaques like this, refer to “Washington’s Headquarters” and make that claim if the Father of Our Country made even a brief stop at the depicted building or scene. But, the Morris-Jumel Mansion is the real deal in that regard.

The Morris-Jumel Mansion was built around 1760 by a British colonel, Roger Morris, who was married to Mary Philipse: some say Mary had previously turned down a proposal from George Washington. Morris’ estate, Mount Morris, covered a vast amount of Harlem acreage, some of which would become Mount Morris Park, now Marcus Garvey Park. During the war, Morris, a loyalist, was forced to vacate the mansion and return to England; it then became a headquarters for Washington in the autumn of 1776. While President in 1790, Washington had a formal dinner in the mansion with John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. [from FNY’s Sugar Hill page]

Some gilded pilasters and cartouches at 550 West 157th Street, just off Broadway. The gilding was just added because Street View from December 2016 does not show it.

FDNY alarm, Broadway and West 158th. This one happens to be an original alarm of this type from 1912. How do you tell? That was the only year the interlocking FDNY logotype was used on the alarm base. In subsequent years, FDNY was spelled out in four separate letters. The shaft at the top used to have a lamp that was diffused by red glass.

One of the oddities in this part of Washington Heights is Edward M. Morgan Place, which runs between Broadway and Riverside Drive at West 157th. It’s examined on this FNY page.

Worth a visit here on Broadway between West 155th and 156th Streets is Audubon Terrace, whose gate is unfortunately locked on Sundays, but can be found open during certain hours during the week and on Saturdays.

The Terrace is an underpublicized mixture of Beaux Arts and American Renaissance architecture. It is home to Boricua College, the Hispanic Society of America, the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Formerly, Audubon Terrace was home to the Museum of the American Indian, which has relocated to the Custom House in Bowling Green (and larger digs on the Mall in Washington, DC), the American Geographical Society (now relocated to Milwaukee), and the American Numismatic Society, now on Fulton and William Streets downtown. Audubon Terrace was commissioned at the behest of railroad heir Archer Huntington in 1907; his wife Anna sculpted the Terrace’s statue of El Cid, the legendary eleventh-century Spanish knight. You will find the names of Native American tribes inscribed on the roofline of the southern wing.

The Latin inscription “ubique” on the bas relief of the globe means “everywhere.”

A new addition to the Washington Heights scene is the Audubon Mural Project, sponsored by the National Audubon Society and Gitler+_____ Gallery. Of course, it honors the artist and ornithologist John James Audubon (see below) whose former property encompassed pretty much everything seen on this page. I did not see all the murals in the project, but did see what could be its most spectacular (see below).

West 155th Street leads downhill to a dead end that is gated off from the Henry Hudson Parkway on its western end. It still boasts a Belgian block pavement, as well as the remnants of fencing that protects a high curb from the sidewalk.

The motto “Hold High the Flaming Torch from Age to Age” is emblazoned on the frieze of the American Academy of Arts and Letters building on Audubon Terrace facing West 155th. The building opened in 1923.

West 155th Street ends under a stone arch carrying the Riverside Drive viaduct, constructed in 1901. This part of Manhattan is hilly, and when the Drive was constructed on landfill, it was placed on an embankment to keep it relatively level. When it traverses Manhattan Valley 30 blocks south of here, it runs on a spectacular iron arch well above street level.

This wall divides the West 155th Street ramp from a higher section of West 155th that conects with the Riverside Drive viaduct.

One of a number of surprises on West 155th — I’ll get to more later — is this rickety walkway that runs under the viaduct and then over the Amtrak railroad tracks and then down to the street level Riverside Drive bike path on a southern extension of West 158th Street that connects traffic to the north and southbound Henry Hudson Parkway.

Uptown Trinity Cemetery

When the Trinity Church cemetery at Broadway and Wall Street had reached capacity by the early 1800s (interments had taken place there since the mid-1600s) the church sought out additional land and, in 1842, purchased a 23-acre stretch between today’s Amsterdam Avenue, Riverside Drive and West 153rd-155th Streets (originally, the purchase touched the Hudson River) from landowner Richard F. Carman, who was building a village of his own along the Kingsbridge Road, which we now know as Broadway. At the time, as far as most Manhattan residents were concerned, this far north was Ultima Thule, although Trinity had also considered parcels in Morrisania in the Bronx and even a section of Green-Wood Cemetery, which had been established in 1838 in far-off Brooklyn.

From the start, despite its remoteness as well as the relative difficulty in traversing its western section, which is built on high, ungraded hills, Trinity Cemetery was a popular tourist destination, as many cemeteries such as Green-Wood, Woodlawn in the Bronx and Mt. Auburn in Cambridge, MA were designed to be before the days of large public parks.

The western end of Uptown Trinity (it is bisected by Broadway, one of NYC’s only cemeteries with a street running through it) can be entered by a wide gate on West 155th Street at the bottom of the hill. There is a smaller entrance gate at Broadway and West 155th, but it’s generally locked. Tucked near the Riverside Drive viaduct wall is the gravesite of Clement Clarke Moore.

Moore (1779-1863) is popularly credited with writing the Christmas perennial A Visit From St. Nicholas. The poem is credited, along with Thomas Nast’s accompanying artwork, with “systematizing” The Jolly One’s appearance of an amiable elf with a white beard, eight reindeer (Johnny Marks added Rudolph to the team a century later) pipe and red robes. The poem ascribed to him was first published in the upstate Troy Sentinel on 12/23/1823. Whatever doubt of its origin comes from the fact that it was published anonymously, and others have claimed authorship in the ensuing decades. He later acknowledged he was the author in letters to his own children, and included it a published book of verse in 1844. Upon his death he was interred in St. Luke in the Fields in Greenwich Village–he had helped organize St. Luke’s in 1820–but in 1899 he was reinterred here in Uptown Trinity.

Uptown Trinity’s mausoleums are Manhattan Island’s only remaining space still accepting “new residents.” Recent interments include Jerry Orbach, Broadway and TV star who played detective Lenny Briscoe on Law & Order, and Main Ingredient singer Cuba Gooding Senior (“Everybody Plays the Fool”)

Most of the mausolea and tombs in Uptown Trinity are much older, some from the 1850s. In the late 19th Century Egyptian iconography was in vogue, like the Watkins tomb here.

A row of graves from the early 1800s. The sun in October angles on them just right to create interesting shadow interplays with the intricate lettering. The stone on the right depicts a sinking ship. This is the gravestone of Arthur Donnelly (1789-1836) recalls the destruction of the Bristol in 1836. After a five-week voyage from Liverpool, the Bristol ran aground on a sand bar north of Sandy Hook, NJ and south of the Rockaway peninsula, and passenger Donnelly assisted in rescuing crew and passengers, dying of injuries sustained during the shipwreck.

Soon after, another sailing ship, the Mexico, also foundered in the same area, leading to reforms in the pilot process.

Since Uptown Trinity opened in 1842, this must be a reinterment, though I do not know the whereabouts of Donnelly’s remains in the three-year span between 1839 and 1842.

Henry Brevoort (1782-1848) and his wife, Laura Carson Brevoort. When 11th Street was being laid out downtown in the 1810s, Henry Brevoort was one of the few landowners in the area with enough pull to prevent a street from being built, as his apple orchard stood in the way. Hence, there is no 11th Street between Broadway and 4th Avenue; instead, the magnificent Grace Church, completed in 1846 by James Renwick Jr., a cousin of the Brevoorts, stands there today. It’s a shame that Henry, whose stone was toppled several years ago, can’t have his gravesite restored.

Brevoort was a great friend of Washington Irving’s, and their voluminous correspondence survives today.

Clear days in Uptown Trinty allow views of New Jersey and the George Washington Bridge. The Cemetery is known for its plethora of Celtic crosses, with cruciform apices surrounded by circles. It usually indicates some irish ancestry for the interred.

At least four NYC mayors are buried in Uptown Trinity. Cadwallader David Colden (1769-1834), born in Queens, was mayor from 1818-1821 and then became a US Representative from New York from 1821-1823. He immediately followed his close friend, DeWitt Clinton, as mayor. In City Hall, he spearheaded the House of Refuge, basically a homeless shelter for teenagers and young adults; it opened in an armory at what would be the future Madison Square in 1825. He also championed a national canal system in Congress.

The family was prominent in the colonial era in Flushing, and one of the north-south streets there is Colden Street. There is also a Colden Avenue in Morris Park, Bronx, where the north-south streets bear 19th Century mayors’ names.

While John Jacob Astor’s (1763-1848) exact gravesite is unmarked, he is interred below the simple shaft marked “Astor Vault.”

In 1779, the German-born Astor emigrated to London, England, where he worked for an older brother, George Astor, who manufactured musical instruments. While there, he learned there was good money to be made buying and selling furs in the United States and in March 1783, he came to New York City where another of his older brothers, Henry Astor, had previously settled and worked for him in his butcher shop. Within three years he established a business buying furs from Native American trappers at the mouth of the Columbia River, and opened his own fur shop in New York City.

By 1795, he had purchased a fleet of 12 ships which he employed to transport his furs to the Far East and Europe, bringing back manufactured goods and tea that he sold in the United States. He established the American Fur Company on April 6, 1808. In 1810, he established Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River.

At the time of his death, he was estimated to be worth around $20 million dollars, over a billion in today’s money.

I have already referenced the Morris-Jumel Mansion on Edgecombe Avenue. Interred here is the Jumel in its name, Eliza Brown Bowen Jumel. Allegedly a former prostitute, she was shunned by New York society, but met with a warmer reception when the Jumels traveled to France. There she charmed Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, who bestowed various gifts upon her, including several pieces of furniture which may still be seen in the Morris-Jumel Mansion. The Jumels’ marital affections ended long before their marriage, however, and her reputation became even more notorious when her husband died in 1832 and rumors persisted that she had deliberately let him bleed to death.

In 1833 Eliza married Aaron Burr, but quickly divorced him. She died at age 90 in 1865.

The leftmost stone in this trio belongs to Samuel Seabury (1873-1958), a renowned jurist who headed the Seabury Commission in the 1930s, investigating corruption in Tammany Hall, leading to the resignation of Mayor Jimmy Walker. He was an unsuccessful candidate for NYS Governor in 1916.

This view is indicative of the steepness of the west side of Uptown Trinity’s hills. In the left background is a ramp that goes to the Cemetery’s West 153rd Street vehicular entrance. The Cemetery offices are located at the bottom of the hill on the left.

Embedded in the stone wall at Broadway and West 153rd Street is one of the two Cemetery monuments commemorating the Battle of Harlem Heights, Washington’s only victory over the British in NYC. This is the older one, from 1901. High ground within what became the Cemetery was the patriots’ first line of defense.

The great author Charles Dickens was one of the first to popularize the book tour and his works, which appeared mostly in serial form, were greatly anticipated. Classics like Oliver Twist and David Copperfield, which champion the lower and middle classes and expose the hard life they were forced to lead in 19th Century Britain, sell just as steadily today as they did when they originally appeared.

Charles’ son, Alfred Tennyson Dickens (1845-1912) lies in Uptown Trinity, marked by a small stone close to the Broadway cemetery entrance. He toured the world as a lecturer on his father’s life and work. While visiting the USA in 1912 (staying at the Astor Hotel) he was stricken by a sudden illness and passed. Trinity Cemetery donated the plot and A. T. Dickens was interred here rather than in his native England. Thus, the author of A Visit From Saint Nicholas and the son of the man who wrote A Christmas Carol are both in Uptown Trinity.

The magnificent Episcopal/Anglican Church of the Intercession, Broadway and the SE corner of West 155th, was designed by famed ecclesiastical architect Bertram Goodhue (and determined to be an “quintessential” Goodhue work) and built 1910-1914 originally as a chapel for Trinity Church, if such a massive building can be called a chapel. The church complex consists of a tower, vicarage, vestry and parish house. It was Goodhue’s favorite among all his works, and he’s here — buried in the transept

His many commissions include the Nebraska State Capitol; the Master Plan for the California Institute of Technology; the campuses for Rice and Princeton Universities, and St. Thomas Episcopal Church, New York City.

In addition to his architectural work, he worked independently as an illustrator and typeface designer, creating the popular Cheltenham style.

Heading into the eastern half of Uptown Trinity, which is accessed by a gate on West 155th at the Church of the Intercession (the other gates on Amsterdam Avenue are generally locked), the first monument you see is the tall Celtic cross for John James Audubon (1785-1851), a naturalist, ornithologist, and a painter who depicted birds so accurately that his works resemble photographs. Audubon lived and worked here beginning in 1841 when northern Manhattan was fields, forests, and streams.

Jean-Jacques Audubon was born in what is now Haiti on his sea captain father’s sugar plantation, and grew up near Nantes, France, emigrating to the USA in 1803 to avoid serving in the Napoleanic Wars, becoming a citizen in 1812. He had always expressed an interest in nature and the outdoors and especially in birds; in 1820 he traveled to the American South to begin his massive project of painting every native bird species in America. At first he could not find a publisher in the States, but his drawings became a sensation in Britain and Birds of America, today an unparalleled classic of its genre, gradually found release between 1827 and 1839.

Just behind the Audubon grave shaft is the North Presbyterian Church.

The Church of the Intercession has competition across the street, at least in the tower department, from the North Presbyterian Church across West 155th. When it was organized in 1847 it was a Congregationalist church, only becoming associated with the Presbyterians (as the Washington Heights Presbyterian Church) in 1858. The construction of this building between 1900-1905 ended the City’s plans to extend Audubon Avenue south to West 155th, where it would have begun opposite the Audubon monument in Uptown Trinity.

In the shadow of the Audubon monument is the gravesite of Elise Mayer Abels, who died in 1858. The stone is remarkable because it is inscribed entirely in German.

Another NYC mayor, Fernando Wood (1812-1881), is buried in Uptown Trinity on the eastern division. He served two separate terms from 1855-1858 and again from 1860-1862, and was a US Representative from NY from 1841-1843, 1863-1865 and 1867-1881. He was born in Philadelphia and was a Copperhead during the Civil War (a Southern ally living in the North) and suggested NYC secede from the USA in order to protect the city’s trade with the Confederacy.

His terms were marred by gang riots and battles between competing police forces; the NYPD had not yet been established.

“He was the handsomest man I ever saw, and the most corrupt man that ever sat in the Mayor’s chair.” –historian George Milton Fort [in Mr. Lincoln and New York]

The second of Uptown Trinity’s Revolutionary War Battle of Harlem Heights markers, near Amsterdam Avenue and West 153rd. It was installed in 1929 by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Ed Koch (1924-2013), NYC mayor from January 1, 1978 to January 1, 1990, late in life knew he would die without heirs and so, purchased this plot before his death and had a tombstone near Amsterdam Avenue and West 153rd Street prepared while he was still living. It was inscribed with the words spoken by Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl before he was beheaded by Islamic terrorists in Pakistan — “My father is Jewish, my mother is Jewish, I am Jewish;” as well as the prayer “Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is one,” found in Deuteronomy 6:4, which is spoken at morning and evening Jewish prayer services; and “He was fiercely proud of his Jewish faith. He fiercely defended the City of New York and he fiercely defended its people. Above all, he loved his country, the United States of America, in whose armed forces he served in World War II.”

Without a doubt this is the most spectacular of the Audubon bird murals I’ve seen in the area, at Amsterdam and 153rd, and JJA himself has a cameo in the upper right corner.

St. Luke African Methodist Episcopal Church (originally Washington Heights Methodist Episcopal), Amsterdam Avenue and West 153rd, across from the cemetery. The cornerstone provides AME info, but the church building has been here since at least 1896, so this is a little confusing.

Heading east on 153rd I was surprised to find a group of extraordinary attached townhouses dating back to the late 1880s. Similar buildings can be found on West 152nd and West 154th and are part of the overall Hamilton Heights-Sugar Hill Northwest Landmarked District, and a detailed history of Sugar Hill, and architectural descriptions of these buildings, can be found on this NYC Landmarks page.

Ragged Glory, at St. Nicholas Place and West 155th Street. I wonder what the story is behind this two-story building, with its trio of arched windows and wind-ripped American flag (which Street View shows has been here since 2014). Each and every building in NYC has multitudes of stories behind it, of the people who have lived there or done business in these places. The apartment I live in, in Little Neck, has had dozens of families, perhaps over 100 people, living in it since it was built in 1941. I’m just the Latest, and whoever replaces me will then take the title of the Latest. You could probably pore over property records and see who was here and at what time, but their stories have been forever silenced.

“Edgecombe” Avenue’s name was aptly chosen because “comb,” in Welsh, “cwm,” is a very old word for hill, and Egdecombe Avenue runs on top of the hill called Coogan’s Bluff, which looks down on the Harlem River and used to look down on the home of the New York (baseball) Giants, the Polo Grounds. Hills in this part of Manhattan are especially steep –we’ve already seen one in Uptown Trinity.

The Coogan in Coogan’s Bluff was James Coogan, Manhattan Borough President, who sold the land to New York Giants owner John T. Brush, who moved the Giants to the second Polo Grounds in 1891. (The first Polo Grounds was on East 111th between 5th and 6th (Lenox) Avenues and yes, it was originally a polo field. The third Polo Grounds was built in 1911 after the second one burned down. The Giants shared the Polo Grounds with the New York Yankees for a few years until Yankee Stadium was built in 1923.

In an unusual situation, the city has already subnamed West 155th Street for Charles Hamilton Houston (1895-1950) an African American attorney who mentored Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and played a big part in dismantling southern states’ segregationist “Jim Crow” laws. However the Department of Transportation had not yet unveiled another honorific sign in October 2017.

I’ve been enamored of the John Hooper Fountain, at Edgecombe and West 155th where they meet St. Nicholas Place, ever since I “found” it over a decade ago. Ostensibly it’s a horse trough for now-vanished Dobbins, but it’s also a founatin for humans, a fountain for dogs, and a streetlamp that was lit up when I previously encountered it (but not this time). To me it’s a miracle that a truck hasn’t taken it out yet.

The fountain was gift from civil engineer/newspaperman/entrepreneur John Hooper. In his will, made public upon his death in 1889, he appropriated funds for the construction of two public fountains that had to include horse troughs as well as drinking fountains. There had been another in Brooklyn at Flatbush and 6th Avenues in Park Slope that disappeared long ago.

In another bit of infrastructural singularity, this fire alarm is mounted on a very short version of the octagonal posts that are usually over 20 feet in height and support streetlamps, painted red in its entirety.

West 155th Street is carried on a pair of bridges, one that carries the roadway over the extremely high ridge on Manhattan’s east side and another over the Harlem River.

The 155th Street Viaduct, originally built for carriage traffic, was completed in 1895, the same year as Macombs Dam Bridge; engineer Alfred P. Boller handled both projects. The staircase and sidewalk railings were originally designed by Hecla Iron Works, which would also design the exit and entrance kiosks for the IRT Subway in 1904. They were restored when the viaduct was repaired in the early 2000s.

Though the railings have been replaced on much of the viaduct, here is a short intact section of the originals. Look at the intricate scrollwork, as well as the square, diamond and circle motifs on the ironwork at the base. Just exquisite.

The Polo Grounds Houses replaced the baseball stadium shortly after the Mets departed it and moved into Shea Stadium in 1964. The old Polo Grounds was the home of the NY Baseball Giants, where Mel Ott, Johnny Mize and Willie Mays played, and the place where Staten Islander Bobby Thomson hit “the shot heard ’round the world” that completed the Giants’ furious comeback after being way behind the Brooklyn Dodgers at the end of the 1951 season.

Next: across the Harlem River and past Yankee Stadium

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

11/19/17