By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

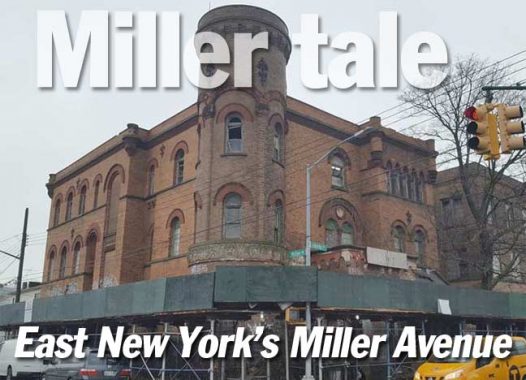

While driving through Cypress Hills and East New York I passed by what looked like an abandoned castle. In this section of the city, I resumed it was either an abandoned church or a former police station. Turns out it was both. But before going into the history of 486 Liberty Avenue, I decided to travel the length of its cross street, Miller Avenue, which runs for 1.6 miles from the top of the terminal moraine at Highland Park down to Linden Boulevard.

From its summit at Crosby Avenue, the view south is dizzying, perhaps the steepest in Brooklyn for a street. On the horizon the bald hilltop is the Fountain Avenue Landfill, proposed site of a future state park, and behind it the apartment towers on Rockaway Beach. If not for the landfill, then the open ocean could easily be been from this vantage point.

In contrast to most streets running below elevated subway lines, the stretch of Fulton Street that crosses Miller Avenue is uncharacteristically quiet and narrow, with one lane of eastbound traffic running in the shadow of the J and Z trains. This structure should not be confused with the old Fulton Street El . That transit line covered Fulton Street from the East River to Broadway Junction, where it turned south on Snediker Avenue then east on Liberty Avenue. After a block of sunshine, the J and Z lines plunge Fulton into darkness again. The old Fulton El was removed in 1940 and replaced with a subway line. Kevin Walsh visited this stretch of Fulton Street in 2015.

It is at Liberty Avenue that we return to this abandoned castle that so richly deserves recognition. Its architect George Ingram was a prolific designer of police stations in the pre-annexation City of Brooklyn. “Palatial Homes for the Wielders of the Club,” is how Brooklyn Daily Eagle described his stations. The 17th (originally 153rd) Precinct opened in 1892, with John Pocahontas Smith as its first detainee, arrested for public drunkenness. With a name like that, he either had Native ancestry or parents with a sense of historical humor. It functioned as a police station until the 1970s, when it was sold to People’s First Baptist Church; currently it is abandoned.

A 19-oughts postcard view of the 153rd.

The dedication plague installed by the church reads “To our Chief Christ Jesus.” Was this supposed to be a police reference, describing the founder of Christianity as a chief? Sadly this castle in not a city landmark and could easily be demolished in favor of a boring brick box.

At the shuttered entrance a fish carving serves as the alternative symbol of the Christian religion, for those who find the crucifix to be too morbid. When Brooklyn was annexed by New York City, its precincts were assigned new numbers as part of the citywide NYPD. The neighborhood is serviced today by the 75th Precinct.

The vine stonework around the precinct’s turret is reminiscent of the fancy flora enveloping the New York State Capitol in Albany, but alas, a far cry from it when it comes to preservation. The church left the castle by 2006, and even the intrepid urban explorers at LTV Squad could not penetrate its fences and walls. In 2008, Rev. R. Simone Lord, fictionalized this building in her book The Last Castle in Brooklyn. Her goal of transforming the castle into a domestic violence victims shelter has yet to be realized.

Interested in more former police stationhouses? Forgotten-NY contributor Gary Fonville documented 14 of them back in 2006.

A block to the south of the old precinct is a church filled with Judaic imagery, Second Calvary Baptist Church at the corner of Glenmore Avenue. Prior to the 1950s, Brownsville and East New York were majority Jewish with a synagogue on nearly every block, many of them carrying the names of Eastern European hometowns. The classical-inspired Agudas Achim Bnei Jacob features a cornerstone with its Hebrew year, which corresponds to 1896. With upward mobility and white flight, the Jewish population in the neighborhood declined to a tiny remnant by the end of the 1960s. The last synagogue in Brownsville closed its doors in 1972.

Most of the former synagogues were purchased by churches and retained their Jewish architectural elements. Details on this history can be read in Ellen Levitt’s book The Lost Synagogues of Brooklyn and Oscar Israelowitz’s Synagogues of New York City.

At Sutter Avenue, the local Jehovah’s Witnesses outpost is a standout by that religion’s standards. Founded in the 1870s, this pacifist sect eschews voting, military service, and political allegiances. Under the leadership of Joseph Franklin Rutherford, their places of worship were dubbed Kingdom Halls. Do not call it a church. On purpose they have a nondescript appearance that avoids architectural decoration, crucifixes, facades and statues. If not for the name on the building, one wouldn’t know that this is a Kingdom Hall.

The final spiritually-related stop no the Miller Avenue tour is Martin Luther King Jr. Park Since his assassination in 1968 countless parks, streets, schools, and highways have been named after the civil rights leader, leading to his birthday becoming a national holiday in 1983. This park’s MLK honor predates the federal holiday, having been renamed for him on May 29, 1970.

Prior to that date this 2.29-acre block of parkland was known as Linton Park after neighborhood developer Edward F. Linton. (1843-1921) Brownstoner gives this forgotten civic leader his due with a six-part online biography. Prior to Linton there was a smaller scale developer in this area named Charles Miller. Could he be the namesake of Miller Avenue? The East New York Project, an encyclopedic neighborhood website, attributes the avenue’s name to Horace A. Miller , another 19th century resident and builder. Nobody in East New York today remembers either of the Millers, Edward Linton, George Ingram, or John Pocahontas Smith. Forgotten-NY is here for them.

A block to the south of Martin Luther King Jr. Park is Livonia Avenue, which has its own detailed Forgotten-NY page. This is where one can take the subway home.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press)

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

2/8/18