By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

On a bend of the East River on Manhattan’s Lower East Side is a park named after this waterway and recently co-named after a former mayor. In contrast to Riverside Park with its Olmstedian layout, complex topography, and access, the 57.5-acre East River Park has only seven entrances along its 1.3-miles of waterfront, with the FDR Drive separating it from the Lower East Side neighborhood. It is a product of Robert Moses, who sought to balance the highway with a park and give this crowded corner of Manhattan much-needed green space.

Historical Overview

Since colonial times this been has been known as Corlears Hook, after the Van Corlear family that owned land here in the Dutch days. As New York’s seaport grew, the entire East River shoreline below Turtle Bay was lined with piers and ferry docks protruding into the water. The area was rough and tumble, known through the 19th century not as the Lower East Side, but as Corlears Hook, a standalone term for the southeast tip of Manhattan. Change came in 1883, when Assemblyman Timothy J. Campbell proposed a waterfront park for Corlears Hook. The park opened on June 22, 1896 on a superblock bound by Cherry, Jackson, South, and Corlears Streets. In the following year a similar slum-to-park project was completed, Columbus Park on the site of the former Five Points.

The design of the park’s initial comfort station resembled the one in Union Square while its circular pathways were reminiscent of Tompkins Square. Corlears Hook Park was redesigned in the late 1930s, with FDR Drive slicing through the park. With the highway project a new comfort station was built, straight paths, and a pedestrian bridge to the new East River Park. By then this old park was much further from the shore while still preserving in its name the original southwest tip of the borough.

Prior to the construction of Williamsburg Bridge in 1903, the ferries at Grand Street and Houston Street took travelers to Brooklyn and points east. The Grand Streets of Brooklyn and Manhattan were connected by boat, as were their two Fulton Streets. The above 1921 Bromley map of Corlears Hook shows Williamsburg Bridge between the two ferry docks. Because the bridge landing was deep inland, the ferries remained a viable transportation option for travelers living and working close to the shore. These two ferries ran until December 31, 1918. The ferry’s Brooklyn landing is today a small park.

By 1930 the Houston Street Ferry was gone. I outlined the present streets on this map. When the city built public housing projects it often preserved existing public schools within the new superblocks. In the process this meant saving small segments of older streets that would not have survived. Thanks to Public School 97, pieces of Mangin, Goerck, and Stanton Streets were preserved within Baruch Houses. Goerck was later renamed Baruch Place, not to be confused with nearby Baruch Drive. Today this building is the Bard College High School, but the lettering above the school’s entrance still has its old name. Its collegiate gothic design is the work of prolific public school architect C.B.J. Snyder, famous for Erasmus Hall and John Jay College, among other places. Back in 2000, Kevin Walsh published a detailed necrology of the local streets that are no longer with us as a result of urban renewal and superblocks.

Near Houston Street’s end at East River was the Third Street Recreation Pier, one of many such parks that projected into the water. Enclosed by a roof, it hosted concerts. The rest of the shoreline in 1930 was still a warren of coal and lumber yards that received their deliveries by boat from their sources in New England.

The dramatic changes began on August 28, 1935 when Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia took the seat in a steam shovel and mowed down the derelict Grand Street Ferry dock. Hundreds of residents and a marching bang cheered him on as construction commenced on East River Park. Like many Robert Moses projects, this was to be a highway with a park. While much of the parkland along FDR Drive comprises of the extremely thin East River Esplanade and a few playgrounds on the road’s inland side, at East River Park, land was extended into the war to create a wide lip of park space.

The shoreline transformation at East River Park was the first of its kind in the city, with 1.5 miles of piers, warehouses, and docks demolished in favor of a waterfront park. This industry-to-parkland on the waterfront includes contemporary examples such as Hudson River Park, Brooklyn Bridge Park, and Gantry Plaza. East River Park was the first such park in the city.

Representative of its decade, the comfort stations in East River Park feature Art Deco patterns around its doors, but certainly not as flashy as its privately-built genre representatives Chrysler Building, and the apartments of Grand Concourse. Behind this comfort station is the Brian Watkins Tennis Center, named after the Utah tourist killedby subway muggers in 1990 while defending his parents. The murder made national headlines and spurred a sustained crackdown on crime in the city. Watkins was in town for the U.S. Open, and it made sense for fellow tennis lover Mayor David Dinkins to name a set of public courts for him.

Pier 42

The southern entrance to East River Park is at Montgomery Street by Pier 42. The last of Manhattan’s cargo piers, it received its last shipment of Ecuador bananas in November 1987. With that final order, the centuries-long role of the East River as an international port had ended. Whatever piers remain on Manhattan’s east side today are either recreational or ferry docks. After nearly three decades of uninspiring use as a parking lot, the pier is being redesigned into an 8-acre park that will preserve elements of the pier shed’s structure.

What is old is new again. 83 years after Mayor LaGuardia demolished the Grand Street ferry dock, a new dock is being built at Corlears Hook for NYC Ferry. The service will connect Lower East Side residents to Wall Street, Midtown, Williamsburg, Long Island City, and Astoria, among other places.

Fireboat Station

Corresponding to Grand Street is a brick tower in the park that is the former FDNY Marine Company 6. This structure dates to 1941 but the first fireboats were moored at this location as far back as 1877. As the industrial use of East River declined, so did the need for fireboats.

In 1994, the FDNY transferred this facility to Parks. It was then leased to the Lower East Side Ecology Center, which installed a green roof atop this former fireboat station.

Brockovich Steps In

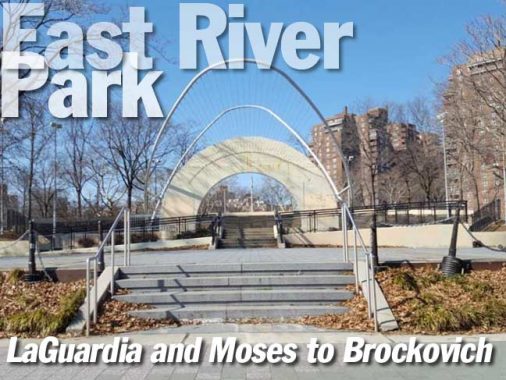

At the bend in the shoreline that is Corlears Hook, an amphitheater fits right in. The present stage was funded in 2001 by consumer rights activist Erin Brockovich as part of an ABC episode titled Challenge America With Erin Brockovich: The Miracle in Manhattan. The project’s budget was $4 million with a 6 day timeframe and pro bono labor provided by Tishman Construction.

The Brockovich bandshell is a humble replacement for the original 1941 theater, which has been in a state of ruin since at least 1973. The above photo is from Parks Archives. Its brief moment of glory was in 1956 when Joseph Papp ran a free production of Julius Caesar here. The following summer his show relocated to Central Park, where it runs to this day.

Water’s Edge

Another long-awaited project for East River Park was its seawall. Nature hates seawalls, sending waves crashing against them until they show signs of crumbling. In the 2001 restoration, the shoreline appears the same as in 1940 but the promenade runs atop piers with a softer riprap shoreline beneath joggers’ feet that absorbs waves and enables for marine life to flourish. At East 5th Street, a cove was carved from the seawall where the public can hear and watch the waves crash. I wish that East River Park had more of such coves.

Across the East River the once-industrial Williamsburg shoreline is having its own transformation with the former Domino Sugar Refinery being redeveloped into a residential complex. A couple of cargo cranes on the property were repainted and preserved as art pieces in a new park. To their left, the smokestack of Grand Ferry Park is visible.

Baruch Bath House

From the park looking inland one notices an abandoned square building amid the public housing towers. This curiosity led me back across the FDR Drive to what was the city’s first public bathhouse and a reminder of when Rivington Street ran up to the East River. The facility opened in 1901 as the Rivington Street Public Bath, vital at a time when many nearby apartments did not have showers and bathtubs. In 19117, it was renamed after Dr. Simon Baruch. The namesake is a pioneering medical researcher who promoted residential restrooms and public bathhouses.

Today the abandoned Dr. Simon Baruch Public Bath is enveloped by the campus of Baruch Houses with Baruch Playground on its side. A 2007 CityArts mural Heat Dances to the Sun’s Beat decorates its eastern side, designed by James Evans and Adam Peachy. Urban explorers tried over the years to get into this ruin over the years but all of its doors and windows have been bricked shut since 1975.

A 1930 property survey shows the Baruch bathhouse surrounded by tenements. I drew a purple line to show everything that will be razed here in the 1950s in favor of public housing and the Baruch Playground (in green) The bathhouse would the lone holdout within this perimeter. Land for the playground was acquired for the city by Simon’s son Bernard Baruch, a noted financier and namesake of Baruch College.

Fortunately the photo collection at Museum of the City of New York has an exterior of the bathhouse from its early years and a shot of its indoor pool. The closest contemporaries of this structure that are open to the public today are the East 54th StreetRecreation Center and the Asser Levy Recreation Center, which have gyms, showers and pools inside Beaux-Arts design buildings.

In the second half of the 20th century as apartments became more sanitary and bathhouses took on a seedy reputation, the Rivington Street Municipal Bath fell into disrepair. It closed in 1973 and has been abandoned since then. Considering the cost of restoring the structure and the existing public pools nearby at Hamilton Fish Park and Dry Dock Playground, it is highly unlikely that this bathhouse will ever have its taps turned on again.

North and South Ends

At the southern entrance to the park is a sign announcing its full name, John V. Lindsay East River Park. In a region where nearly everything was once named after its location the recent trend is now to honor politicians. Ed Koch for Queensboro Bridge, Herman “Denny” Farrell for Riverbank State Park, etc. For all the merits of honoring Mayor Lindsay, give the man his own plaza or monument, but why rename an entire park? Besides, there’s also a drive inside Central Park carrying his name.

At the northern tip of East River Park the path narrows between the highway and the water’s edge. The massive 14th Street power plant dominates the skyline, the last industrial giant in a corner of Manhattan once known as the Gashouse District. Much of this former neighborhood is today’s Stuyvesant Town.

Looking north from Avenue D, the smokestacks have the look of a precisionist painting. Think of Charles Demuth or Charles Sheeler. Their works can be found at the Whitney Museum. Having gone far from East River Park, time to end this tour and return on another day to see what else is left of this old district.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press)

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

3/6/18