Con Dead

Time has proven the enemy for our magnificent brick power plants in recent years. The Long Island City Penn Station powerhouse, with its four iconic smokestacks, has been converted to residential use, minus the smokestacks, and the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit (BMT) powerhouse on 500 Kent and Division Avenues, shown above in February 2007 and at left in August 2008, has had its date with the wreckers’ ball and has been pulverized to oblivion. The grand building was built in stages between 1906 and 1936, at first powering Brooklyn’s street cars and el trains and later, in 1950, it was sold to Con Edison, which used it as a powerhouse for nearly 50 years.

It will be luxury towers, so I hear.

The Navy Yard entrance at Kent Avenue and Clymer Street was once a northern extension of Washington Avenue. RIGHT: fire alarm stub, rendered pink by constant sunlight exposure.

A large warehouse containing salt used on NYC’s roads during ice storms or snowfalls is directly across the street from Jacob’s Ladder playground. The park’s name has a convoluted and interesting history. Let Parks explain it all for you:

Jacob’s Ladder is a plant that can be found in temperate zones throughout the world. It refers to any of the 25 species that are classified in the Polemonium genus. Many of these species are cultivated in gardens, and can be recognized by their clusters of drooping blue, violet, or white flowers that bloom in late spring. The flowers are shaped like a funnel and typically have five petals. The leaves of the plants are normally oriented in a pattern that resembles a ladder, and thus the popular name. When crunched, certain species’ leaves emit a pungent smell, which has given rise to the alternative popular name skunkweed. Several species are also known for their ability to thrive in wild habitats ranging from shady forests to sunny meadows. Jacob’s Ladder can even be found growing in the rocky soil on mountaintops and along roadsides.

Native Americans used a preparation of Jacob’s Ladder to clean their hair and treat certain skin conditions. Europeans also cultivated various species because of their supposed medicinal purposes. The herbalist Culpepper (1616-1654) claimed that one species could effectively treat harmful fevers and “pestilential distempers.” It was also useful in the treatment of trembling, heart palpitations, headaches, and nervous conditions. In fact, the genus Polemonium takes its name from a medicinal plant associated with the Greek philosopher Polemos of Cappadocia.

The plant’s popular name is derived from a biblical story in the Old Testament Book of Genesis (Chapter 28: 12-22). Isaac instructed his son Jacob to leave Bersheva and go to Charan to find a wife. On his way, he stopped to rest for the night and had a vivid dream. In it, he saw a ladder in the sky upon which hosts of angels were witnessed ascending and descending between earth and heaven. Standing above Jacob, God promised to bless Jacob and his children, and to give them the land on which Jacob had been sleeping. When Jacob awoke, he took the stone he had used as a pillow and set it upright as a pillar, which he then anointed with oil. He named the place Bethel, and resolved that if God were to protect him, then he would honor God and make the pillar the House of God. According to many, the spot where Jacob slept and received his revelation was the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. The ladder symbolizes the connection at that place between this world and the higher world — and the promise made between God and Jacob.

The park, and adjoining Roberto Clemente Park, were created in 1999 after old and decrepit buildings were razed on the east side of Kent Avenue in 1996. The two parks were likely given names associated with the Latino and Jewish communities to reflect the main population demographics in the area.

A modern residential building has been built along a short stub of Morton Street.

In NYC, to keep out criminals, we must jail ourselves. Some prison bars –er, window guards — have begun to rust already here.

Pole dancer; Clemente Park; now-demolished section of 500 Kent Avenue

Schaefer Landing, 440 Kent Avenue and South 9th Street, is a 2-building, 350-unit residential development designed by architect Karl Fischer and completed in 2006. (It was among the first vanguards to take advantage of a 2005 zoning change allowing new residential builings in the waterfront area.) The short riverwalk is a nice touch, as is the Coke bottle green color scheme and Water Taxi stop (the latest I’ve heard, though, is that monetary considerations have eliminated winter service, and the nearest public transit is the B61 bus on Bedford (northbound) or Driggs (southbound); the hike to the nearest subway/el, Marcy Avenue, is a seven-block walk on Broadway). I have not seen the interiors, but I’d have to think the builders didn’t think through the public transportation access here.

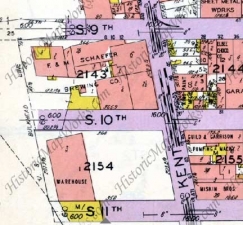

Schaefer Landing is so named because it occupies the lot where Schaefer beer was brewed for many years. Prussian immigrants Frederick and Maximilian Schaefer founded the brewery in 1842, producing one of the first lagers in America. After occupying several locations in Manhattan, Rudolph Schaefer, the son of Maximilian who had ascended to CEO in 1912, sold the plot that became home to St. Bartholomew’s Church on Park Avenue and looked across the river to Williamsburg to build and expanded plant. Schaefer operated in Brooklyn exactly 60 years, from 1916 to 1976.

Are there any traces of the Schaefer brewery left today? A building now used as a synagogue on Kent and North 9th features a chiseled figure in concrete on the facade: a hand holding up a brimming glass, surrounded by hops leaves.

At South 8th, the sun made a guest appearance (it had been behind clouds for much of the walk so far) and illuminated the Williamsburg Bridge, at the time celebrating its 105th anniversary. Work began on the bridge in 1896 with Leffert Lefferts Buck as chief engineer, ?Henry Hornbostel as architect and Holton D. Robinson as assistant engineer, and the bridge opened in 1903.

No poetry has been written about it, as Hart Crane did with the Brooklyn Bridge. No songs have been written about it, as Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel did with the 59th Street (Queensboro) Bridge. No one ever attempted to sell this bridge. Indeed, before it was ever completed, the span was described by John DeWitt Warner as a “surrender of the City Beautiful to the City Vulgar.” While not renowned for its beauty, the Williamsburg Bridge has fulfilled its original mission to relieve traffic congestion on the Brooklyn Bridge, and to serve as an important link between Manhattan and the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn…. nycroads.com

LEFT: Buildings on Kent Avenue just south of Broadway. I was intrigued by the ivy-covered light post in the parking lot for the Kabbalah Energy Drink distributor.

Whoa, Domino

According to local legend, when this recently-shuttered sugar refinery at Kent Avenue and South 4th-5th Streets was still humming, the smell of caramelized sugar could be sniffed in the immediate vicinity. The plant, instantly recognizable from the J train on the Williamsburgh Bridge or from boat traffic in the East River by its huge illuminated sign, shut down in early 2004 after about 125 years in business. The exterior of the factory and the red neon Domino sign on an adjoining building have been landmarked, but the site has been slated to be refurbished and rehabilitated as luxury housing. Plans have called for 2200 apartments to be constructed in buildings of 30-40 stories, which would dwarf the brick plant.

Domino Sugar was founded by English immigrant William Havemeyer, who had worked as a supervisor in a cane sugar ?refinery and arrived in New York in 1799. With brother Frederick, he established a sugar refinery on Vandam Street in Manhattan in 1807; by 1816, the Havemeyer Company was producing 9 million lbs. of sugar annually. The founders’ sons, Frederick Jr., and William F., built a modern refinery on the Williamsburg waterfront in the 1870s; after it burned, the present 10-story building was constructed in 1882. The Havemeyers, meanwhile, had a Williamsburg street named for them by 1886, just a few years after they had begun their operations in Brooklyn.

The site’s owner, Katan Group and Community Preservation Corporation Resources, plans to break ground for their new residential development in 2009, but some area residents have questioned the need for new luxury housing in a soft market [2009] and would rather see it developed as galleries, housing for artists, and “affordable” units. Bob Guskind of the Gowanus Lounge put the “New Domino” on deathwatch at the end of 2008: Although we hear rumors that there is financing for this multi-billion project on Kent Avenue in Williamsburg and the plan is to phase it in over a decade, we’re not looking for a groundbreaking. We think this one is sunk for some time to come.

The employee parking lot has been empty for several years.

Passing 289 Kent, I was struck by the shape of the brackets that mark the ends of steel rods that in lage part support the building. I knew I had seen that shape before.

The brackets are, unquestionably, pattered after the snout of the common Star-Nosed Mole, which uses its 22 fleshy appendages to make its living finding grubs and worms. The two holes are the animal’s nostrils; the mole is mostly blind, since it spends most of its time in the unlit underground.

What could have once been waterside hotels or brothels, 245 and 229 Kent Avenue

Kent Avenue takes a further turn northeast at Grand Street. The intersection isn’t busy enough to warrant a stoplight, though it does have a Cyclops.

Grand Ferry Park

It’s hardly grand and here’s no ferry here, but the city has taken steps to upgrade what was once a patch of grass, a smokestack and some rocks along the East River shoreline, and come up with a tidy park at Grand Street’s western end…

…The Grand Street Ferry ceased operations in 1918, and the abandoned landing became one of the few stretches of Williamsburg’s shoreline accessible to the public. In 1974, the Parks Council, an advocacy group, created an unofficial park in the space using recycled materials; later the land was acquired by Parks in order to ensure its permanence as a park, and sufficient funding for its repair and maintenance. The 1.55 acres of land was transferred to Parks on October 1997.

The new park, located between Grand Street, West River Street, and the East River, officially opened on July 9, 1998. The design incorporates elements from the site’s history. A red brick smokestack rising above a circular pattern of cobblestones was part of a molasses plant that Pfizer Pharmaceuticals used in the early 20th century for work that led, eventually, to the large-scale production of penicillin. The cobblestones were salvaged from the section of Grand Street where the park was constructed.

In 2008, the park landscape was reconstructed with new plantings, paths and drainage. NYC Parks

Grand Street extends several miles east to the junction of Broadway and Queens Boulevard in Elmhurst, Queens. In the mid-1920s the stretch in Queens became known as Grand Avenue.

At 184-198 Kent Avenue between North 3rd and 4th we find the Austin Nichols warehouse, the object of a tug -of-war between developers and preservationists. The building, which was fairly nondescript even before it was placed into its presently scarred condition, is at present being stripped of its longtime white paint job. It has a pedigree, though: it was designed by renowned architect Cass Gilbert and constructed in 1915.

LEFT: Northside Piers towers over the Austin N Ichols building as seen from River Street, August 2008.

The Austin, Nichols & Co. Warehouse is one of the largest and most significant structures on the Brooklyn waterfront. Financed by Havemeyer & Elder, it was designed and built to serve Austin, Nichols & Co., the world’s largest wholesale grocery business. Established by James E. Nichols and five former associates of Fitts & Austin in 1879, the company grew to occupy nine buildings in Manhattan before moving to the Eastern District Terminal. To realize his first architectural venture, Horace Havemeyer (1886-1957) assembled a team of seasoned professionals, including Cass Gilbert (1859-1934), architect of the U. S. Custom House and Woolworth Building. Construction of the warehouse began in January 1914 and the plantwas fully operational by March 1915. Measuring 179 by 440 feet, the plant was described by a contemporary writer as a “Model of Modern Construction and Efficiency,” integrating piers, railway tracks, freight elevators, conveyor belts, and pneumatic tubes. Under the Sunbeam Foods label, all types of products were prepared, processed and packaged in the building, from dried fruit and coffee, to cheese, olives, and peanut butter. In 1934 Austin Nichols entered the liquor business and the building remained its headquarters until the late 1950s. nyc.gov, where much more is available.

More on the railroad tracks a little later on. The NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission actually designated the building for landmark status in 2005 but then rescinded the designation. A compromise of sorts was reached in 2008: the interior can be hollowed out and extra stories placed on top but the exterior can’t, apparently, be messed with, unless a new coat of paint is called for.

Duff’s

Duff’s, one of Brooklyn’s premier biker/metal bars, packed up and moved to a new location at Broadway and Marcy Avenues in December 2008 — the management sensed things were getting a touch chichi in western Williamsburg. Duff’s was still here on Kent Avenue and North 3rd in the shadow of the Austin Nichols warehouse when I sauntered past in August. I haven’t been in Duff’s — let owner Jimmy Duff himself tell you what it’s all about, from their official website:

Duff’s is the metal mecca in NYC – It’s about a lifestyle, not a marketing strategy. What you’ll get – cool people/music, cheap drinks, and great service in an original, truly one of a kind environment. DUFF’S also features a large outside deck that’s open year round’, where you can enjoy a smoke with your drink, safe from Smoking Police, and use our large public grill for cookouts. What you won’t get – Corny/corporate promotions, overpriced “umbrella” drinks of any kind, asshole “buzz kill” patrons, and no yuppies around for miles.

Duff’s wasn’t built for mass appeal – it’s not for everyone – either ya get it , or ya don’t. Take a look around the site , it’s a decent representation of what we’re about – If you’re feelin’ it, come on down and check it out. I’ll buy ya a fuckin’ drink & we’ll rock out & have a good time. That’s what Duff’s is about.

Man of 1,000 Bars at Duff’s

LEFT: Miss Williamsburg Diner, latterly “718” was converted into an Italian restaurant awhile back. Is it still open? It is one of three ‘classic’ diners in the area once serving dockworkers and now have ‘hauted’ their menus up a notch to cater to a new clientele. The other two are the simply-named Diner on Broadway and Berry Street, and Relish at Wythe Avenue and North 3rd. This NYTimes article from a few years ago discusses all three. RIGHT: yellow, arch-windowed warehouse, Kent Avenue and North 1st.