By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

I’ve never climbed Everest, or Denali, but locally I can brag about scaling Mount Marcy, the state’s highest point; Todt Hill on Staten Island as the city’s tallest hill; and in my hometown borough, that distinction goes to the grounds of North Shore Towers at 258.2 feet above sea level.

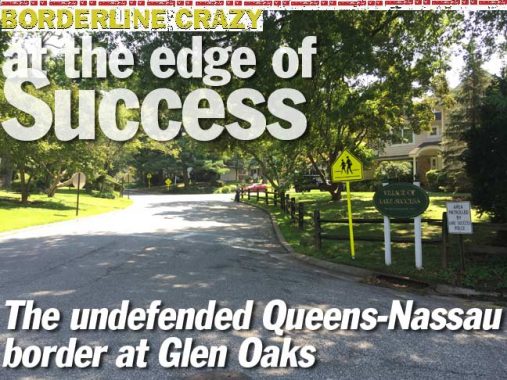

I did not have time to trespass onto the grounds of the borough’s last privately-owned golf course, so I looked in from the Grand Central Parkway service road. In contrast to many European cities, which have civic monuments and symbolic gates at their borders, the line separating the borough of Queens from Nassau County is unmarked. But a trained urban explorer knows where the city ends and suburbia begins.

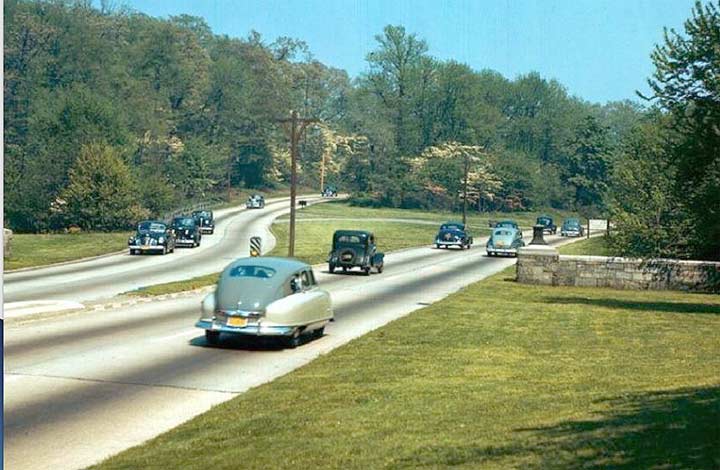

When Grand Central Parkway was constructed in the 1920s, it was a four-lane drive through a park-like route with generous green shoulders, medians, wooden lampposts, and stone arch bridges. The popularity of automobiles resulted in the road’s widening to six lanes and installation of metal lampposts. Visually there’s little to distinguish today’s urban parkways from expressways other than the low bridges and truck restriction. Looking back at a postcard from the parkway’s early years, we see the city line clearly marked with a stone wall. The widening of the road eliminated this geographic curiosity.

Today the border’s presence is subtle. At the exact line, the gray metal city lampposts end their march. Beyond are the curved black color lampposts of Long Island’s parkways. The city’s “Speed Limit 50” signs increase to “State Speed Limit 55.” Another sign bears the logo of Northern State Parkway, the suburban continuation of Grand Central Parkway. Finally, the concrete median is grassy on the Nassau side of the border. For travelers entering Queens, signs are posted on the border reminding them not to turn right on red lights, a rule specific to New York City.

Another sign of the border is that in Queens the parkway is lined by service roads. The north side road ends abruptly at the border, beyond which lies the Village of Lake Success.

The south side service road continues into Nassau County as Marcus Avenue and it predates the parkway that took away most of its traffic. At the border, the suburban speed limit of 40 is reduced to 25. Its first traffic light connects to a driveway for North Shore Towers.

Hewlett Avenue parallels the borderline between Grand Central Parkway and Long Island Expressway in a section of Little Neck known as Deepdale. Once the estate of William K. Vanderbilt Jr., it was developed as a golf course and later as tract housing. Beyond the borderline, golf continues its game around the shores of Lake Success. The name has nothing to do with affluence. It is an English corruption of a Native word. Old maps also label the glacial kettle water trap as Lake Surprise.

The streets of Lake Success are distinct from those in Deepdale. There are no sidewalks or metal green street signs. No plastic picket fences or brick walls here. Restrictive covenants ensure that lawns are plentiful and visible, with just a few wooden plank fences permitted here.

Lake Success does not have the oversize Mediterranean-style McMansions of Queens, but its single-family homes have their own individual designs, including a ranch residence inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Unlike the highways, streets that cross the city line do not tell travelers where the county changes. Kevin Walsh looks down and notices changes in the paving and house numbers. Here one can straddle the borderline.

On the 1956 Skyviews aerial survey, we see the Long Island Expressway running through the forested terrain on its way east. Lake Success is still bucolic with its golf courses and palatial properties while the Queens side of the border has its grid entirely complete. On Marcus Avenue the large parking lot belongs to the Sperry Corporation, a defense contractor whose facility was temporarily used as the UN headquarters from 1947 through 1952. The plant closed in 1998 and today serves as a campus of offices.

Are things still being made in Queens? A couple of blocks inside the border is the E. Gluck Corporation headquarters. Its namesake Eugen Gluck is a Holocaust survivor and longtime resident of Forest Hills. He has been making watches since the 1950s, with Armitron as his best-known brand.

In the heart of Deepdale is Challenge Playground, a 2.04-acre park that is a standard 1950s design. The real curiosity here are the three antennas (antennae) towering over the neighborhood.

These sentinels belong to the Federal Aviation Administration, a reminder that the borough is home to two airports and Deepdale is near its highest natural point.

Surrounding the playground and the antennas is the Deepdale Gardens co-op, a set of attached residences with generous lawns sprawling across 60 acres. Built in 1951, the 1,396-unit campus was designed by Benjamin Braunstein was the largest federally sponsored housing cooperative built to serve the veterans. The same architect also designed Electchester and Glen Oaks Village.

The style here is colonial-inspired, with red bricks, porches, and generous lawn space. The brochures for Deepdale come from the Columbia University Libraries collection.

Returning to the Glen Oaks side of Grand Central Parkway, the high point of queens is topped by North Shore Towers. Formerly the Glen Oaks Country Club, these 33-story towers can be seen from at least ten miles away. For drivers heading towards Queens on the parkway, they serve as a highly visible border marker. The towers share certain characteristics with Co-op City and Starrett City in their height, surrounding open space and locations on the periphery of the city. When the golf club sold its property to builders in 1971, there were concerns about overdevelopment. In a compromise, the towers were built on a small portion of the site, and most of the golf course was preserved.

On the southern border of the golf club 267th Street has the appearance of a countryside lane that predates the arrival of tract houses.

To the south of the North Shore hilltop is the Glen Oaks co-op, built around an oval-shaped park with streets laid out in concentric circles.

From the New York State Archives, a 1951 aerial survey shows the recently completed Glen Oaks Village alongside the Creedmoor farm that is today’s Queens County Farm Museum. A few centuries from now historians or maybe space aliens will look at maps of the circular streets and presume at their center was a temple or civic center. In reality, it is a humble park with a playground and little league field. The center of Rego Park’s crescents is even less distinguished. Not even a park at its center.

Glen Oaks Oval is one of five city parks that have this shape. There’s also Smokey Oval (Phil Rizzutto Park) in Richmond Hill, Queensboro Oval underneath its namesake bridge, O’Brien Oval in the Bronx, and Williamsbridge Oval, the most beautiful of all the oval-shaped parks. Glen Oaks Oval is co-named after local civic leader Jerry Tenney.

The oval lies on the former route of Long Island Motor Parkway, a privately-owned road that operated from 1908 through 1938. Along the southern edge of the Farm Museum, a dirt trail road runs on the former parkway.

The campus of the LIJ Hospital stretches from 263rd Street beyond 271st, the last numbered street towards the city line. It is a collection of modernist brick buildings, and postmodernist glass and steel facades that evoke a self-contained city. The campus includes a small park for patients and visitors. Behind this park lies Nassau County.

As with my previous photo essays, a couple of historical maps tell the story of this borderland. A 1922 map from the Library of Congress shows the prescribed street grid covering the borough. Alley Pond Park makes its appearance, but it is smaller in size in comparison to its present shape. The planners of that time did not expect Douglaston Park Golf Course, North Shore Golf Club, and Oakland Country Club to survive. The first two did, while the third was redeveloped as the campus of Queensborough Community College.

The 1946 Hagstrom atlas of Queens and Nassau Counties shows Grand Central Parkway in green. Under Robert Moses’ administration, parkways were designated as park access roads, earning them park and transportation funding. Initially maintained by the Parks Department, they have since been transferred to the state DOT. Horace Harding Boulevard would be upgraded to an expressway by 1958. LIJ Hospital was still a couple of years from its groundbreaking and the Motor Parkway is seen running across its site as a bicycle path. In reality, the path runs only from Cunningham Park to Winchester Boulevard. There is a movement to extend the path east through Creedmoor towards the city line. Underhill Avenue was mapped to follow Motor Parkway. In reality, only the portion following Kissena Corridor Park East was completed. Its namesake was a local family that spied for the patriots in the American Revolution. Their descendants owned land in eastern Queens into the late 19th century.

For further exploration of this borderland, be sure to follow Kevin’s 2006 border walk in Floral Park, or my 2015 essay on the time when Union Turnpike was a state-designated route.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

9/7/18