By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

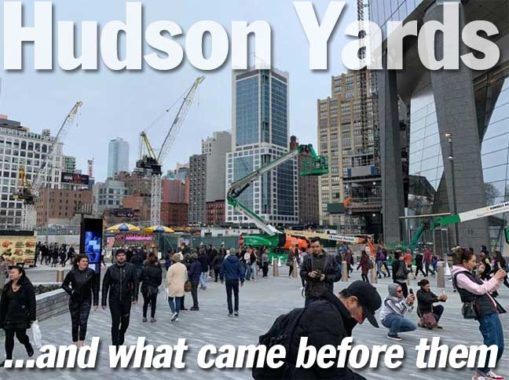

The newest neighborhood in Manhattan is promoted as something new where nothing stood before, a blank slate atop a railyard that awaited development. The $55 billion Hudson Yards neighborhood opened in March 2019 with a six block park and boulevard, a privately-operated public square with a sculpture, million-square-foot retail center, performance space, offices, and residences, connected to the rest of the city by the 7 subway line extension.

Emerging from the very deep underground Hudson Yards terminus of the 7 train, I was surrounded by a cityscape of glass box towers. The city that produced iconic spires such as Empire State and Chrysler now has the same generic look as any other city. But it’s the inside that counts- offices with jobs, jobs, jobs! I can defend that, but not the astronomically-priced luxury residences. The weird sculpture in the distance? At the cost of $200 million, Thomas Heatherwick’s The Vessel has stairs and elevators rising to 16 stories.

But with glass towers surrounding it, comparisons to the Eiffel Tower are as nonsensical as vertically sliced bagels. On my visit to Hudson Yards, it appeared deceptively empty from afar but when you get close, that’s where one finds long lines. And one must reserve in advance to experience The Vessel. On each stair landing, there are no artworks, sculptures, or poetic signs. The landings are all empty by design!

I walked back to 34th Street for a look north, which has only the second post-millennial road in Manhattan that has Boulevard in its name. The first is in Riverside South, also built on the site of a railyard. Behind the cranes and between the boxy glass towers, I spied a couple of red brick walkups. If buildings could talk, they would tell us about the neighborhood before it was handed over to luxury developers with nearly $6 billion in tax breaks and incentives. After learning this, Amazon HQ2 for Queens doesn’t sound so bad.

I continued north along Hudson Boulevard. Really it doesn’t fit the description, as we usually expect boulevards to have extra width for traffic and considerable length. As with its fellow post-millennial Riverside Boulevard on the Upper West Side, the toponym seems designed for top dollar land values. I would’ve called it Hudson Parkway as the road runs for only six blocks alongside a linear park.

This new boulevard is paralleled by a park between 33rd and 36th Streets. Its designer is a familiar one to post-millennial New Yorkers: Michael van Valkenburgh whose other works include the open space at Federal Plaza, Brooklyn Bridge Park, and Teardrop Park. The park’s first three blocks opened in 2015 with the goal of extending it to 39th Street. Initially designated as Hudson Yards Park, it was renamed in March 2019 after Bella Abzug, the tough-talking big-hatted Congresswoman who spoke up for feminist, anti-war, and LGBT causes. Her former district covered the west side of Manhattan.

At the northern tip of the park (as of April 2019), the gray arch cornice of 527 W. 36th Street, an auto repair shop will soon bite the dust as Hudson Boulevard marches north. The purchase of the garage and its transformation into a park is thanks to developer Tishman Speyer, which in return received the right to build a taller tower next to the park. The appearance of the garage hearkens to the time when everything around here was industrial.

This brings us back to how Hudson Yards appeared before the glass-and-steel towers rose up from the ground. Unless otherwise noted, credit here goes to Percy Loomis Sperr, whose works are kept at the NYPL Digital Collections. Besides the massive rail yard, the neighborhood has a forgotten train terminal at 30th Street and a wholesale market. At 34th Street and 11th Avenue, meat, fish, and produce was sold from 1871 to 1938 at Manhattan Market, an impressive Victorian structure that is an ancestor of today’s Hunts Point Market. Daytonian in Manhattan tells its story in detail. The 2.1 million-square-foot Javits Center stands on this site today, a Crystal Palace of the late 20th century.

During Sperr’s visit to the 30th Street Yard, the changing skyline was evident with Empire State Building overlooking the tracks. On a return visit to the yard in 1940, Sperr documented Eleventh Avenue being built atop the tracks, connecting the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood to Chelsea south of the yard. The recently-completed High Line and Starrett-Lehigh Building can also be seen here.

Reaching back to 1905 in the NYPL collection, we see Eleventh Avenue crossing dozens of tracks at grade, befitting of its nickname at the time as Death Avenue for the dangers posed by trains crossing the avenue.

Predating Penn Station by a half century, trains traveling down the west side of Manhattan began terminating at W. 30th Street and 9th Avenue beginning in early 1861 with President-elect Abraham Lincoln as the first passenger. After his assassination in April 1865, his funeral train also stopped here. The construction of Grand Central Terminal took away most of the passengers from 30th Street Depot. It soldiered on as a freight terminal through 1933, when the Morgan General Mail Facility replaced the depot. Sperr photographed its ancient tracks and platforms in 1927.

The Morgan facility was built at the same time as the high Line, when freight tracks along the west side were elevated to the south of the rail yard, and depressed in a trench to its north. A spur of the High Line used to run inside the 1.4 million square foot facility that also had its own tunnel connecting to the nearby general post office.

That spur was still undergoing its rail-to-park transformation in early 2019. At is tip, the space titled as Plinth will host a giant sculpture evoking African American history.

A few yards from this spur the High Line curves to the south. Here, one track retains its pre-park appearance while visitors are squeezed onto a narrow walkway.

Returning to Hudson Yards, the High Line has a new neighbor: the city’s largest structure on rails. The Shed has a retractable shell that turns its performance space into a an outdoor venue, weather permitting. Unlike the glass boxes around it, here’s a truly sculptural building that is movable. It is creative in its appearance and purpose, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro and the Rockwell Group, the firms that worked on the High Line.

Looking west towards Eleventh Avenue and the Hudson River, one recognizes that soon these tracks will also be covered by towers and a public space. This section of the yard has been the subject of development proposals since the 1950s, the most memorable of which were a new Yankee Stadium in the 1990s and an Olympic stadium in the 2000s that would also host the Jets football team.

The massive convention center is best known for its auto, boat, and comic shows. Its best secret is its 6.75-acre green rooftop, the largest of its kind in the country. It serves as a habitat for birds and bees. Be sure to take a public tour.

Before Javits Center appeared as the post-industrial pioneer on the West Side, Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. proposed an $87.3 million convention center and observation tower on reclaimed land along Twelfth Avenue. The proposal was presented to the press in tandem with Battery Park City. While the latter became reality, the former did not. By the early 1980s, further land reclamation proposals such as Westway were cancelled for environmental reasons.

In 1967 the city proposed a miniature airport titled Stolport on the Hudson shoreline facing the rail yard. This was the first serious proposal for an airport in the borough of Manhattan since Mayor LaGuardia’s plan to build runways on Governors Island. Although Stolport did not get very far, its location on a sliver of shoreline between road and water is a heliport today.

The heliport at 30th Street is part of a much more ambitious plan from 1956 that included a sizable Cunard dock between piers 33 and 37. Its design resembles that of Pier 40, which was completed in 1962.

Not having found images online of a West Side Yankee Stadium, we fast forward to the first decade of this millennium, when the city applied to host the 2012 Olympics. The stadium was designed for 80,000 seats, dozens of rooftop wind turbines, and a park atop the West Side Highway. Madison Square Garden owner James Dolan opposed the stadium, as did then-Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, and civic groups in the surrounding neighborhoods. The Games instead went to London.

The firm Kohn Pedersen Fox had a second version of the stadium that was also designed to stand atop the railyard and fit into the Manhattan street grid. A year after the defeat of the stadium in 2005 the city issued a request for proposals for Hudson Yards. The developer Related Companies secured the winning bid.

At the time, the massive size of the John. D. Caemmerer West Side Yard contrasted with the rest of Manhattan where glass towers were rapidly popping up. At the portal to the yard is 450 West 33rd Street, a brutalist box with sloping walls that used to host the Daily News, WNET, and Associated Press offices. It has since been given a glassy postmodern facelift.

The upscale mall of Hudson Yards resembles The Shops at Columbus Circle. Same developer, architect, appearance, and clientele. At one entrance, a wall with the Hudson Yards logo was used as a backdrop for selfie-happy visitors and #HelloHudsonYards. Although it was free of charge, I did not stand in that line.

All this glass architecture brought to mind the site’s name two and a half centuries earlier when it had the Glass House Farm. The map here was published in 1873, long after the glass works and farm were consumed by industry. Matthew Earnest established a glass-making business in a section of Manhattan called Newfoundland in 1758. It survived to the outbreak of the American Revolution. Subsequent property owners used the property as a farm but kept its name.

In 1800, a portion of the site was given its own grid in an attempt at development, but it did not work out. This mini-grid contained three east-west streets: Rapelje, Jersey and Schroepel; and three north-south streets: Moses, Maple and Tulip. Rapelje is an old Dutch colonial name that also appears on a Brooklyn street. Also noteworthy: the ancient Fitzroy Road that followed the route of today’s Eighth Avenue. There’s a condo building in Chelsea named Fitzroy, in honor of the historic road. A 2BR apartment here begins at $4.9 million. Glass House Farm was subdivided in 1830. The railroad arrived in the neighborhood sixteen years later.

By 1867 as shown on the M. Dripps map, the Glass House Farm was a blurry memory for New Yorkers as the site was undergoing an industrial transformation. Railroad tracks can be seen running up Eleventh Avenue, with their terminal on 30th Street. Globe Iron Works is the biggest business in the neighborhood, located on W. 33rd Street near Eleventh Avenue. It operated until around 1920. As a reference, I circled the future site of The Vessel and highlighted 34th Street.

Looking at the master plan of Hudson Yards by the firm Kohn Pedersen Fox, one should expect more towers and parkland, connecting to the northern terminus of High Line, but surprisingly no bridge across the West Side Highway to Hudson River Park.

At this point, I was ready to go home and descended into the city’s newest IRT line station: 34th Street-Hudson Yards, where the Funktional Vibration mosaic by Xenobia Bailey offered something colorful inspired by folk art and pop culture.

The long escalator reminded me of Moscow’s legendary subway while the curved walls and tiles resembled nearby Lincoln Tunnel. It is the only subway station in America with an incline elevator. While in many older subway terminal stations the tracks end abruptly, here they extend south to 28th Street, used for train storage and a possible extension maybe a century from now.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/7/19