I recently took a walk from Penn Station, exploring the newest and final section of the High Line that will open to the public, into Chelsea, south along 4th Avenue and the Bowery, and across the Manhattan Bridge. In times past I would put together a 150-photo epic page describing and illustrating the walk, but these days I’m content to chop it up into sections, like record labels did in the old days with popular albums, periodically promoting “singles” consisting of the songs they thought would sell best for radio play.

I don’t have a marketing research department (years ago I was trying to put one into place but it didn’t work out) so I don’t know what stories or photos will get people to click on the ads or sign up for tours — if I had the magic knowledge I’d take advantage of it — but I do save time and, I’m sure, Forgotten Fans’ patience by composing shorter pages, and so shorter it is. Today, I’ll concentrate on West 21st Street, which I had never really walked down before except for short stretches here and there, on its western section through Chelsea.

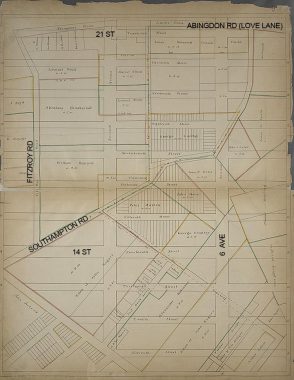

It turns out that West 21st Street largely parallels the roadbed of a colonial-era roadway that existed long before the current street grid was surveyed and laid out in the early 1800s. This, a plate courtesy the New York Public Library, is a section of John Randel’s grid survey map compiled through painstaking research and survey work between 1805 and 1811. Future numbered streets in the grid are listed — I have named a few here — but notice that teh grid is placed atop several pre-existing roadways.

As the grid was gradually built as property owners sold off their parcels to the city, these roads — many based on the routes of Native American trails — gradually were used less and less and faded from existence as houses and businesses were constructed in their roadbeds. On this map, no trace exists of Fitzroy Road, which ran east of 8th Avenue, or Southampton Road, which cut a northeast path across the newly planned grid. Only Broadway remains as an aboriginal road that was allowed to survive.

As it happens, West 21st Street largely parallels one of these original roads, Abingdon Road, also known popularly in the colonial era as “Love Lane.” The road’s proper name comes from the Earl of Abingdon, the son-in-law of Sir Peter Warren, a Royal Navy officer who owned much of the territory in Greenwich Village and some of Chelsea before the Revolutionary War, including the triangle of property now occupied by Abingdon Square at Hudson and Bethune Streets.

The High Line has frequent exits onto Chelsea streets. A storefront on West 20th Street displays the name “Under Line Coffee,” taking advantage of its location beneath the trestle.

At 10th Avenue and West 20th-21st Streets the west end of the General Theological Seminary, an Episcopal institution, comes into view.

Thomas Clarke, a retired British seaman, bought acreage in this area (roughly between West 14th and 23rd Streets and 7th Avenue west to the river), naming it for Chelsea Hospital in London, a facility corresponding to NYC’s Sailors Snug Harbor, a retirement place for retired seamen. His son was Clement Clarke Moore, of ‘”Twas the Night Before Christmas” fame.

Architect George Coolidge Haight designed and built the various Gothic Revival buildings of the Seminary, including the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, between 1827 and 1902. The Seminary grounds had been an apple orchard owned by Clement Clarke Moore, an academician who was Professor of Oriental and Greek literature, as well as divinity and biblical Learning at the General Theological Seminary, which had been founded in 1817; Moore donated part of his property for the new Seminary buildings. Moore anonymously published the holiday poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” in a Troy, NY newspaper in 1823; he did not publish it with a byline until 1844. Moore’s depiction of Santa Claus in the poem, combined with Thomas Nast’s depictions, helped to solidify The Jolly One’s present image. The Seminary has a magnificent library and the campus, accessible from 9th avenue, is an urban oasis of quiet.

From one worship-based institution to another, the Roman Catholic Church of the Guardian Angel, 193 10th Avenue at West 21st Street, sits catercorner from from the General Theological Seminary. The parish originated on West 23rd Street in 1888. The original church had to be torn down in the early 1930s to make way for the West Side Elevated Freight Railroad — today known as High Line Park, which faces the back end of the church. The New York Central Railroad, therefore, funded this new Sicilian Romanesque church that was completed in 1930 with John Van Pelt as its architect. Lavish bas reliefs on the 10th Avenue side depict Biblical scenes in order from Genesis to the Apocalypse.

The parish parochial school on 10th Avenue was built at the same time as the church and shares its Sicilian Romanesque design.

A Queen Anne-style apartment building at 192 10th Avenue, across from Guardian Angel church and school, is home to the independent bookstore 192 Books; bookstores, independent or chained, are increasingly rare in the Amazon Era.

A well-preserved trio of houses on the landmarked block of West 21st at the corner of 10th Avenue, #469-473. They are Italianate walkups constructed in 1853.

Here’s #439-443 West 21st, on the north side of the street. Most residences on the north side of the block face the Greater Theological Seminary on the south side. Once again, all three date to 1853, a good year for architecture in Chelsea. In the 1910s, the center house, #441, was the home of poet Wallace Stevens, whose “Sunday Morning” was deemed by critics to be among the finest of the genre in the 20th Century.

It’s unusual to see small brick and frame buildings facing major north-south avenues in Manhattan but there’s a group of them here in Chelsea on the west side of 9th Avenue north of West 21st. Nos. 185-189 are small wooden structures built from 1856-1868 for James N. Wells’ real estate interests. The brick building on the corner is actually the oldest, constructed in 1831-1832. Wells himself lived in the building for a few years beginning in 1833. Later, he would occupy a handsome Greek Revival house at #162 9th Avenue at West 20th Street, and then several more homes in fashionable neighborhoods.

It was Wells who along with Clement Clarke Moore, the author of “A Visit From St. Nicholas,” who began the development of modern Chelsea in the 1830s. Even though Moore opposed the grid plan that would ultimately divide his landholdings in western Manhattan, he knew where his bread was buttered and sold subdivisions to wealthy New Yorkers, complete with covenants that specified what could and could not be built on the properties. Stables, factories and slaughterhouses were out. Even today, Chelsea, with its attached suburban-ish homes on side streets between about West 17th-West 22nd Streets, has a pleasant, small-town uniformity about it.

The faded sign on the brick building a few doors down from his old house carried Wells’ name for over a century until the sun finally bleached it out of existence.

One of the “supertall” Hudson Yards towers, with an observation deck that will be NYC’s highest when it opens in 2020, looms over the old buildings.

PS 11/Middle School 260, #320 West 21st between 8th and 9th Avenue sports an immense piece by OsGemeos, Brazilian brothers Gustavo and Otávio Pandolfo, in collaboration with NYC’s Futura. Hard to see here but the boy’s pants contain small versions of flags from many nations. Futura 2000 (Leonard McGurr, 1955- ) has painted for many years and began along with late legends Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat in the late 1970s. Futura’s voice can be heard on The Clash’s “Overpowered by Funk” on their 1982 Combat Rock album.

#323 West 21st, between 8th and 9th, has the red-painted doors of a firehouse, and when it was built in 1865 at the end of the Civil War that’s what it was. It’s still labeled as The Old Chelsea Firehouse. However, it only served in that capacity for a few years before it was subdivided into separate residences around 1875. Dancer Franziska Marie Boas established a studio in the building in 1933 that lasted about two decades. In 1949 she leased part of it to an artist who had arrived in recent years from Pennsylvania named Andy Warhol.

On a West 21st Street gate at #305 can be found a recreation of the most famous scene from George Mélies’ groundbreaking 1902 film A Trip To the Moon. Decades later, the Smashing Pumpkins based the award-winning Tonight, Tonight video on Mélies’ film. According to John Tauranac in his 2018 book Manhattan’s Little Secrets, the gate was commissioned in 1997 by a group of documentary filmmakers whose offices were in the building. It was designed and produced by Philadelphia ironworker Warren Holzman.

Probably the most famed image of Albert Einstein, the great German physicist who discovered that mass equals energy times the speed of light squared and proved the theory of relativity — basically the building blocks describing how the universe works — is Einstein playfully sticking his tongue out, photographed by Arthur Sasse in 1951.

The image appears on the side of 212 8th Avenue at West 21st, home to the Vibe lingerie store on the ground floor, formerly the Rawhide club.

#256-262 West 21st Street east of 8th Avenue, a group of Anglo-Italianate attached houses constructed in the mid-1850s. Tom Miller describes its colorful and occasionally tragic characters in this Daytonian in Manhattan entry.

The Beaux Arts (ca. 1900) #272 and 274 West 21st.

A pair of brownstone guardians, whose faces have worn down over time, at #211 West 21st.

The School of Visual Arts was founded in 1947 by Silas Rhodes and Burne Hogarth in 1947 as the Cartoonists and Illustrators School, becoming SVA in 1956. It’s an accredited college with a faculty of 1000 and a student body of 3000 scattered among its campuses: the main one at East 23rd and 2nd Avenue in Gramercy Park, the Lower East Side, and several buildings on East 21st between 6th and 7th Avenues.

Though I attended a competitor school, the long-defunct Center for Media Arts on West 26th Street (where I learned Photoshop and QuarkXPress skills that carried me through nearly 15 years of employment) I did attend a class in this SVA branch to brush up on my Adobe Illustrator skills, though no one will claim I have any artistic skill.

The five boroughs are chock full of odd little cemeteries, left over from long-gone family homesteads, or from churches or congregations that have since moved away. The greatest concentration of these is in Queens and Staten Island, but Manhattan has a few as well — the New York and New York City Marble Cemeteries off East 2nd Street in the East Village, for example, and the three Shearith Israel Cemeteries in St. James Place in Chinatown, here on West 11th off 6th Avenue, and 10 blocks north on West 21st off 6th.

Shearith Israel was the only Jewish congregation in New York City from 1654 until 1825. During this entire span of history, all of the Jews of New York belonged to the congregation. Shearith Israel was founded by 23 Jews, mostly of Spanish and Portuguese origin. The earliest Jewish cemetery in the U.S. was recorded in 1656 in New Amsterdam where authorities granted the Shearith Israel Congregation “a little hook of land situated outside of this city for a burial place.”

This is one of three remaining Shearith Israel cemeteries in NYC, and the “newest,” in use from 1829-1851. The oldest of the three is on St. James Place near Chatham Square in Chinatown, and the other, much of it obliterated when West 11th Street was built, is on that street east of 6th Avenue. The one here on West 21st is the largest.

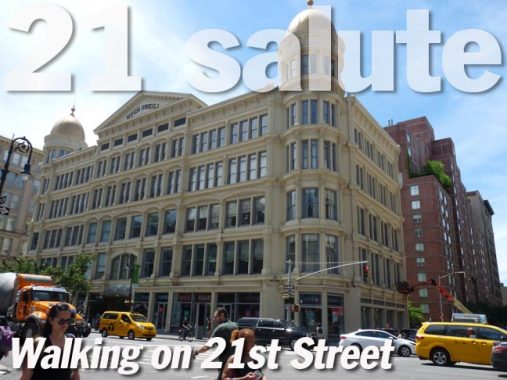

Who is Hugh O’Neill, and why is his name on this building high above Sixth Avenue and 22nd Street? Back in the good old days, circa 1900, Hugh O’Neill owned the building, and the store on the ground floor. Just about everything here has been changed in some way, except the building. Formerly it was part of the so-called Ladies Mile strip along Sixth Avenue in the 20s, featuring department and dry-goods stores.

In the 1990s, Ladies Mile rebounded after this stretch of 6th Avenue had sunk into decrepitude in the 1970s, as new stores like Bed, Bath and Beyond occupied the older emporium buildings. The Hugh O’Neill building even regained its former gilded pair of domes.

The northwest corner of 6th Avenue and East 21st, while in the landmarked Ladies’ Mile district chock full of large emporia, presents a stretch of Italianate buildings of varying heights built in the 1870s. On one is a painted ad for a former tenant, the Wolf Paper & Twine Company. Founded in 1916, the company was located here until 2003.

The massive Adams Dry Goods Building, #675 6th Avenue, was built for the company founded by Canadian Stanley Adams in 1900-1902, designed by architects DeLemos and Cordes at the height of the Beaux-Arts era. In 1907 Adams sold out to competitor Hugh O’Neill and went out of business completely by World War I. The building has had a number of uses, among them a Hershey chocolate factory and for storage by the US Army. You may remember the massive Barnes and Noble bookstore on the ground floor in the 1990s and 2000s.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

6/30/19