To amuse myself before the football games came on, I decided to walk from my home in Little Neck all the way to 71st/Continental Avenue in Forest Hills. It was a rare 67-degree day in January. The route I chose was one of only two available to walkers, because there is a barrier of parks and expressways separating Douglaston and Little Neck from the rest of Queens. I could have used Northern Boulevard, which runs through Udalls Cove, over Alley Pond Park and over the Cross Island Parkway, but I had done that countless times on foot, in a bus and on my bicycle. Instead I swung south, along West Alley Road, the only survivor of a group of “alley” roads in eastern Queens. The “alley” in question runs through a valley carved out by a trickling waterway running south of Little Neck Bay. Few roads traverse it.

I then traveled generally along 73rd Avenue and Jewel Avenue west through Flushing Meadows to Forest Hills. The low January sun was in my eyes much of the time, but the temperature was pleasant. I mostly walked through Oakland Gardens and Fresh Meadows. Before mid-20th Century, these realms were dominated by golf courses, country clubs, and farms before that. Today, they feature clusters of garden apartments — but the development of the last century couldn’t erase all of these areas’ history, and I’ll concentrate on some of it here.

GOOGLE MAP: LITTLE NECK TO FOREST HILLS

Unlike most of my walks I didn’t have to take a train or bus to my starting point. I began at my home in Westmoreland Gardens, a co-op development on Little Neck Parkway and 40th Avenue, built in 1941. I have lived here since 2007, hard to believe it’s almost 13 years now. It’s convenient to get to Manhattan, Port Washington, or points between, as it’s 2 blocks from the Long Island Rail Road.

Westmoreland Gardens is named for a subdivision of Little Neck called Westmoreland, whose boundaries are Little Neck Parkway, 39th Road along the LIRR, Northern Boulevard, and the Queens-Nassau line just short of Nassau Road. It was laid out and built by the Rickert-Finlay real estate company in 1905. Even today, the original Westmoreland covenants, which mandate lawns without fences, slanted roofs, and other features, still apply. Details can be found at the Westmoreland Association website.

Try as I might, I cannot find the name of the architect of the distinctive PS 94, at Little Neck Parkway and 42nd Avenue, constructed in 1914. This building replaced a one-room schoolhouse located at Little Neck Parkway and Bates Road, now the site of a Mormon church.

Here’s a 1909 map excerpt showing Westmoreland and its neighbor development, Marathon Park. As you can see few houses had yet been built in Marathon Park and the area is still sparsely settled. The street layout is still essentially the same as today, though most of the roads have been renamed since 1909.

Two property owners’ names stick out: John Waters and B.H. Cutter. Bloodgood H. Cutter was a potato farmer, poet and acquaintance of Mark Twain, who immortalized him as the “Poet Lariat” in his travelogue, Innocents Abroad. Twain poked fun at Cutter as a master of doggerel who annoyed fellow passengers on an excursion to the Holy Land in the book. The John Waters on the map was a Matinecock Indian who owned the parcel between Broadway (Northern Boulevard), Marathon and Little Neck Parkways. Waters lived for over a century.

As Yogi would say, when you come to a fork in the road, take it. This is the Y-shaped junction of Little Neck and Marathon Parkways; I chose the tine on the right, Marathon Parkway. The developers of Marathon Park originally envisioned a Greek-themed development, but only one other street in the area, Thebes Avenue, carries the theme.

This first address on Marathon Parkway is something of a mystery regarding its age. Some reports have it being as old as the mid-to-late 1800s, while others date it to the 1930s. Its basic salt box design certainly harks back to an earlier age.

This house, along with a smaller one at Little Neck Parkway and 43rd Avenue, are each occupied by members of the Waters family, Matinecock Indians with histories going back to the pre-colonial era before the Dutch arrived.

Two separate architectural philosophies at Northern Blvd. and Marathon Parkway, the former Bryce Rea real estate office on the corner and the newer office building in the background. The borough’s smallest Stop & Shop is out of the picture on the right. While other Stop & Shops, Fairways (see below) and Wegmans’ are palaces of produce, Little Neck’s is quite modest.

Pickings are a bit slim as far as pizza goes in Little Neck; I can count only three pizzerias and one is Aunt Bella’s, a sitdown Italian joint at Marathon Parkway and Beechknoll Avenue. I’m a frequent customer for their pizza and chicken parm. The other pizzeria is Toskana at Northern Boulevard and 249th. Both pies are equally good, while distinct.

South of Northern Boulevard, Marathon Parkway widens, on average. But it does so in fit and starts, widening and then narrowing as it does here. To make the street width consistent, there would have to be negotiations with homeowners along the route.

Turning right (west) on Van Zandt Avenue, which is a Tudor wonderland of sorts. I have always desired one of those A-frame cottages. Van Zandt Avenue is not named for Bruce Springsteen guitarist/Sopranos actor Little Stevie Van Zandt, but rather an early Douglaston patentee. Major Thomas Wickes, a patriot originally from Huntington, owned the entire Douglaston peninsula jutting into Little Neck Bay after the Revolutionary War, and subsequently sold it to Wynant Van Zandt in the 1810s. Scotsman George Douglas purchased the peninsula from Van Zandt in 1835.

Douglaston Parkway has varying widths, as well. When these roads were dirt paths, their widths varied and after they were built up, the varying widths remained.

The anchor tenant at the Fairway shopping mall at Douglaston Parkway and the Long Island Expressway is pretty much all that’s left here, and it looks like Fairway as an entity is cooked as well, as the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in early 2020. The stores will have to be sold off, and they will either disappear or change to other supermarkets. Except for the supermarket, the mall is largely deserted.

Grimaldi’s Pizza, Movie World, and other tenants are still on the signboard, but they’re no longer here. Back in 1996, when Tickle Me Elmo was the hot Christmas toy, John Gotti Junior, son of the famed mobster and still a mobster himself, desired an Elmo or three for the kids in his family, and most of the toy and department stores were sold out. Needless to say, when he visited the Toys “R” Us here in Douglaston, some Elmos turned up, according to legend.

There is a tidy area of attached houses south of the mall, between Douglaston Parkway, 242nd Street, and 65th and 70th Avenues. There’s a dead-end, semiprivate street in the layout though, that isn’t given a street number, with the house numbers behaving as if they’re on Douglaston Parkway even though they’re on a cul de sac off of the parkway. It still has a collection of rather low davit lampposts, some of which still have 1960s mercury Westinghouse Silverliner fixtures.

In 1790, and even well into the 20th century, there were few good roads in eastern Queens. What is now West Alley Road runs through a valley between two hilly areas left by a retreating glacier 150 centuries ago, and the lone road through was called “the alley” on early maps. A number of roads through the area took its name. In the early 19th Century, Alley Road became Douglaston Parkway and East Alley Road became 61st Avenue; only West Alley Road retains its old name.

The area now constituting the 635-acre Alley Pond Park was occupied by the Matinecock Indians in the precolonial era. After their violent ouster by Thomas Hicks in the 1700s the region remained mostly rural with exception of mills harnessing water flowing into Alley Creek. A general store, Buhrman’s, in the Alley surprisingly survived between 1839 and 1929. The store went out of business and was razed when the City acquired the acreage to turn it into Alley Pond Park in the latter year. The new park’s ribbon was cut by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in 1935. Kettle ponds left over from a passage of a glacier 10,000 years ago still dot the area.

A postcard view of Buhrman’s General Store, which doubled as the area’s first post office, shows how rural the area still was in 1925 when the card was mailed. [Eugene Armbruster, photographer]

The Cross Island Parkway, part of the NYC Belt Parkway system along with Shore Parkway and Laurelton Parkway, connects Bay Ridge with the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge and accesses several other bridges and routes. It was built between 1934 and 1940. It briefly enters Nassau County between Jericho and Hempstead Turnpikes as it skirts Belmont Park. Its interchange with the Long Island Expressway was rebuilt in 2005. No trucks or buses are permitted on the CIP, as its overpasses are too low to allow them.

Where West Alley Road meets East Hampton Boulevard and 233rd Street, an unobtrusive small plaque is set in stone on the sidewalk. You’d miss it if you weren’t looking for it.

“George Washington traveled this road on his tour of Long Island, April 24, 1790. Commemorating this event, the Matinecock Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution, Flushing, New York have set this mark.

May 25, l934.”

President Washington visited the plant nurseries of Flushing in 1789 and made a return visit to Queens and the rest of Long Island on a five-day swing the following year. Beginning April 20, he made a 165-mile round-robin journey from Brooklyn to Jamaica, Long Island’s South Shore, Patchogue, north to Setauket, Smithtown, Huntington, Oyster Bay, Roslyn, and Flushing, returning home to his Manhattan mansion on April 24. Washington was on his final leg of the tour when passing Alley Road.

Washington’s principal concern on the trip was the condition of the soil; the USA in the pre-Industrial Revolution era was mostly farmland. The use of fertilizers and techniques like crop rotation were yet untried in Long Island at the time. The President also wanted to personally thank patriots in Long Island who had risked their lives as spies during the Revolutionary War.

Cloverdale Boulevard has all the earmarks of a failed major north-south route. I’ll explain. Before World War II, the area in eastern Queens in which it runs, mainly southern Bayside, was the province of first open fields, then farms, and then country clubs and golf courses such as the Oakland Gardens Golf Club. As Sergey Kadinsky explains in the linked article, the golf club was sold off in parcels, with part of it going to the State, which redeveloped it as Queensboro Community College and Benjamin Cardozo High School. The rest of the golf club and land surrounding it were developed as tract housing and garden apartment complexes.

Cloverdale Boulevard was constructed to run on the east end of QCC and runs in fits and starts from 46th Avenue and 223rd Street generally southeast to Union Turnpike, though it’s interrupted frequently by the Long Island Expressway (it’s not bridged), an arm of Alley Pond Park, and even by the Long Island Motor Parkway, constructed by William K. Vanderbilt as the first express auto route between the Queens-Nassau line and Ronkonkoma, extended west to about Francis Lewis Boulevard in 1926.

It’s a wide, two-lane road for most of its route, suggesting that it was originally planned as a major north-south route. It never shook out that way, though. Its name has always reminded me of the Cloverfield monster-movie series.

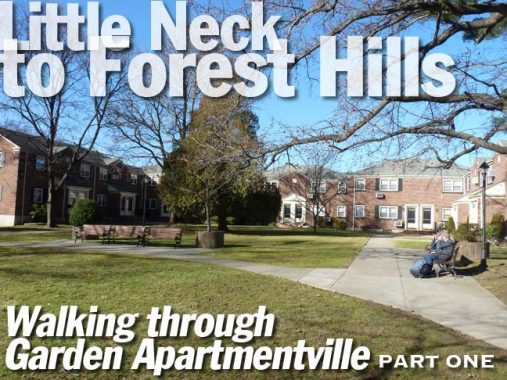

Pressing west along 64th Avenue, I plunged into the Land of Garden Apartment Complex, in which two-story apartment buildings sit in spacious, grassy lots, separated by walking paths. One after the other they come: Cloverdale Gardens of Bayside east of Springfield Boulevard, and west of it, The Estates of Bayside.

More vast complexes can be found between Flushing Meadows and Alley Pond Parks and south of the Long Island Expressway. The Fresh Meadows complex is the largest of these and comprises what can be called a small city within New York City. Prior to World War II, these lands were occupied by empty fields, farms and as we’ve seen, golf and country clubs. In Little Neck, I live in one myself, Westmoreland Gardens, though it’s of smaller scale and preceded World War II. After the war, garden apartment complexes spread like wildfire.

I turned west on 73rd Avenue to make the long trip to Fresh Meadows in earnest, passing through more garden complexes. There’s a strip of eateries at 73rd and Bell Boulevard that includes the Bell Diner and Buddy’ss Kosher Delicatessen.

Bell Park Gardens and Hollis Court Gardens, on the north side of 73rd Avenue either side of Bell Boulevard. The entire south side is taken up by the rather vast Windsor Park Apartments.

We’re on the northern edge of Hollis Hills. The name “Hollis” pops up frequently in eastern Queens. In 2015, I wrote about the reasons for this, as well as some vintage Hollis Hills photos from 1940:

According to the New York Times, the name “Hollis” comes via Frederick W. Dunton, the first developer of the area, which was once known as East Jamaica. He was a native of Hollis, New Hampshire. Originally, Hollis, a parallelogram defined by 180th Street, Francis Lewis Boulevard, Hillside Avenue and 104th Avenue and bisected by Jamaica Avenue, was settled by the Dutch and centered around the present intersection of Jamaica Avenue and Hollis Avenue, which was once called Old Country Road.

During the Revolutionary War, General Nathan Woodhull was captured by the British at the Increase Carpenter tavern in 1776; according to legend, when the Brits ordered him to proclaim “God Save the King” he instead said, “God save us all” and earned a sword bludgeoning, for which his arm was later amputated. He was sent to a prison ship in Gravesend Bay, but a more sympathetic British official had him transferred to onshore house arrest, but he died later in the year.

Dunton developed several neighborhoods surrounding Hollis, many of which carry “Hollis” in their names, including hilly, exclusive Holliswood, now south of the Grand Central Parkway, and more middle-class Hollis Hills, to the GCP’s north. General Colin Powell, activist Al Sharpton, humorist Art Buchwald and Atlanta mayor, later UN ambassador Andrew Young lived in Hollis, as did hip hop entrepreneur Russell Simmons and old-school rappers Run-DMC.

73rd Avenue runs through Cunningham Park between 199th and 210th Streets. Cunningham Park consists of 358 acres, some of it being maintained wilderness. The park also boasts several mountain bike trails (unaware of how winding they are, I was temporarily lost on the trails in June of 2015!) Most of the park’s playgrounds and athletic fields are located on the stretch along Union Turnpike east of 193rd Street, and along 73rd Avenue between Francis Lewis Boulevard and the Clearview.

Cunningham Park was developed in separate parcels acquired by the City between 1927 and 1945 and, after a short stint as Hillside Park, was named for NYC Comptroller W. Arthur Cunningham (1894-1934). After a distinguished military career, Cunningham was a rising star in NYC politics until his premature death from a heart attack. A bronze bust of Cunningham was installed in his namesake park, but it is currently on display at the Forest Park Overlook while its base awaits rehabilitation.

73rd Avenue itself has an interesting story. It’s one of Queens’ oldest routes and turns up on maps as early as the 1850s as Blackstump Road. The story I’ve heard about Blackstump Road is that farmers would burn and blacken tree stumps and use them to mark their property lines, and a small village called Blackstump was located a bit west of Hollis Hills.

This overpass over 73rd Avenue just west of Francis Lewis Boulevard carried the Long Island Motor Parkway. The Parkway was the first major automobile route in Nassau and Suffolk Counties after William K. Vanderbilt opened it in 1905. However, the road did not run west into Queens until 1926 and a series of overpasses like this one were built to carry it over other major roads at the time. I give the full story of the Motor Parkway, the “Long Island 45,” on this FNY page. Since 1938, when it was decommissioned, it’s been used as a pedestrian and bike path as most of its Queens route run in Cunningham and Alley Pond Parks.

Next time: west into Fresh Meadows, Electchester and Forest Hills

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

2/16/20