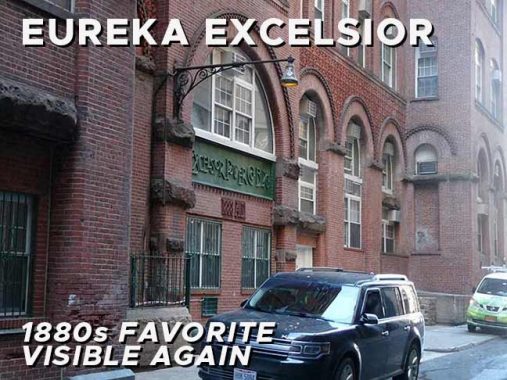

I’VE written about the Excelsior Power Company building before since I have known about it for years before Forgotten New York was a twinkle in my eye. But now, in 2022, there’s something special about it, because for the first time in years, it’s actually visible. Much of Gold Street in lower Manhattan has been completely shrouded by construction sheds but in February, the portion obscuring the Excelsior has been removed, at least temporarily, and so we are vouchsafed a view of this notable building once again.

Gold Street weaves through Lower Manhattan on a not-quite-straight narrow line, reminding us that this part of the city was not built for automobile traffic. Although immigrants may have been regaled with stories about how the New York streets were paved with gold, Gold Street has nothing to do with the precious metal. Instead, it was named for a flower, the celandine, called gouwe by the Dutch. The British, who had a unique talent for boiling down Dutch names for easier pronunciation, eventually Anglicized the name to Golden Hill; it was the site of a confrontation between the Sons of Liberty and British troops in 1770, presaging the war to come.

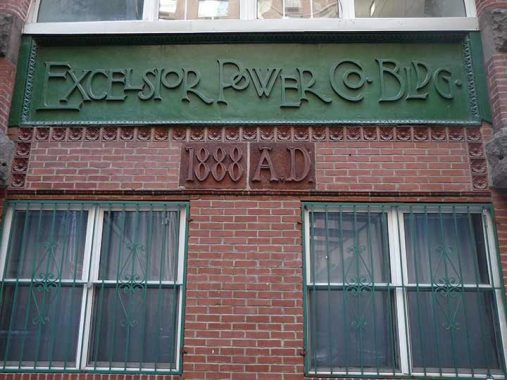

At 33 Gold, just north of Fulton Street, you’ll find three reminders of old New York. Architect William Grinnell constructed the Excelsior Power Company building here in 1888, and its huge, gorgeous blue-green cast iron sign, with its intricate lettering, has been pretty much undisturbed since. The building originally housed coal-fired electric generators.

The Excelsior Power Company Building was designed by William Covington Grinnell, the architect’s only known design in the city. the Excelsior Power Company Building’s above-ground stories were rented to tenants, particularly those in industrial sectors, while the steam plant was in the basement. For the full history of the building, see the Tom Miller “Daytonian in Manhattan” page.

Look at that intricate 1880s-era lettering! This is likely the largest extant example of it you will find in New York City. Just wonderful. And that carven “1888 A.D” below it is almost as good, look at that horizontal serif at the apex of the “A” and those roundels that frame the sign.

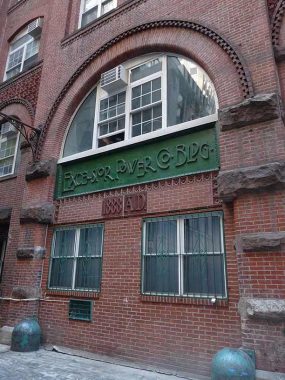

Next to the cast-iron sign, a 1910s-vintage wall-bracket lamp, with original metal scrollwork and incandescent luminaire, can still be found. In the 1940s, it was outfitted with a cone-shaped “junior bell” incandescent light, which had not lit up for quite a few years. Lo and behold, it now has a new bulb, which I found out about because it was “dayburning.” I do wish a glass reflector bowl could have been found to complete the renovation, and the lamp could use a paint job but at least it’s working again. It’s likely the only working “junior bell” remaining in NYC.

Another feature of note: this was once the freight entrance; Belgian-blocked sidewalks are often tell tale signs of this. The large bricked arch gives that away as well. In 1888, horse drawn wagons would have entered here, and had rather more maneuvering room as Gold Street was not lined with skyscrapers as it is today.

Because of that it is rather difficult to get a picture of the entire building for the last few decades; this is about the best you can do.

Hopefully, this exterior will not regain its sidewalk shed and be available for architecture aficionados to delight in for decades to come!

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

2/24/22