Every once in awhile I walk one of Manhattan’s cross streets because I find a number of things along them interesting. I don’t usually walk the entire street river to river, but sometimes that happens. I have done it for 53rd Street, 14th Street, 125th Street in Manhattanville and Harlem, 155th Street, and most recently, 46th Street.

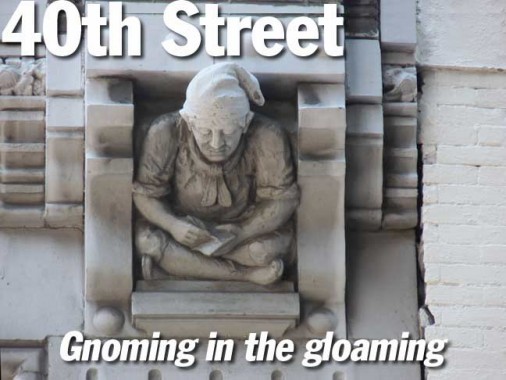

Why 40th Street? Gnomes. I have noticed that the buildings on 40th have an inordinate amount of sculpted figures, some human, some monstrous, all a part of architectural stylings that have become completely abandoned over the years, and the identity of which remain mostly a mystery to me. They’re symbolic, but of what? During my research on this page, I hoped to discover some of that.

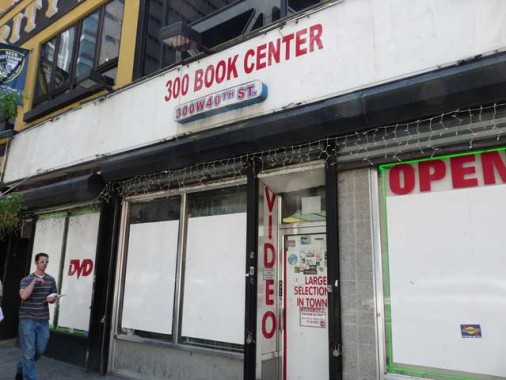

I began at West 40th near 8th Avenue — I didn’t have time today to walk all the way west to 12th, and then double back. This is the south side of West 40th, and on the block, as well as some of 8th Avenue — though a little more of it disappears with every passing year — you can find remnants of the sleez of years past, though the dirty book/video palaces announce their wares not with boobs in your face, as in the good old days, but with blank white paper covering the windows. And, not all of the block is like this, as there are a couple of new hotels and a parking garage further west near 9th Avenue.

The reason for the continued cleanup of this stretch of 8th Avenue is the 2007 high-rise New York Times Building, which was designed by Renzo Piano and came with convenient ladder-like structures on the exterior that daredevils took advantage of when the building first appeared. This took the place of several longstanding businesses, among them some more dirty video stores and the last branch of Knox Hats remaining in NYC. Oddly, all 4 buildings that have been New York Times HQ in NYC still stand: on Park Row and Spruce Street, the Times Tower on Broadway and West 42nd, the NYTimes offices on West 43rd between 7th and 8th, and this place.

Upscale tenants like the Dean and DeLuca gourmet deli and Muji, which is sort of a Japanese Woolworth’s. The atrium is open to the public, of which I was unaware so I didn’t go in. I likely would have been gang tackled if I started pointing my camera at anything.

The construction of the Times Building did cost West 40th a landmark of sorts — at the old 275 West 40th there was a glorious faded ad for shoulder-pad company Seely Shoulder Shapes. On average, every 4o years, women like to go about looking as if they can play left tackle for the Green Bay Packers, and we’re due for another round in the 2020s.

8th Avenue between West 39th and 40th is still a glorious mishmosh of honking cars and stink in the summer as the avenue almost literally sweats. A long-dead travel agency still advertises its destinations on a high-rise wall.

I used to spend a lot more time in the Port Authority Bus Terminal than I do now. The old barn was constructed in 1950, while the large superstructure with the X-shaped girders appeared in 1980. I think I have taken a bus from here 2-3 times in the last 30 years, but when Palisades Park, NJ was open, my parents and I would take a line that left from here. I can’t remember the name of the line but the buses were colored orange and black. I’m sure someone will remember them, especially if they are of A Certain Age.

For me, though I did enjoy amusement park forays (I have always been too much of a yellow-livered, knock-kneed coward to ride the roller coasters) getting there was just as fun as the destination — I would always be looking out the windows for old lampposts or unusual signs. So I always enjoyed riding buses. One or the other parent would always be trundling me onto the the Brooklyn buses, the B-16, B-37, B-63, B-64, B-16 or even the B-35, which ran on Church Avenue as far as Brownsville — just to ride. Then we’d pay the driver for the return trip and go back.

236 West 40th is home to another peep show palace. But this building, with its corbelling and arched windows, has a timeless quality and undoubtedly is one of the oldest on the block. The sign in a second floor window says “Time Out Massage.”

Midtown Comics, on 7th Avenue, has members of the Merry Marvel Marching Society on its side window. Aside from Forbidden Plant and Jim Hanley’s Universe, Midtown is the best-known funnybook store in Manhattan.

“561 7th Avenue [NE corner of 7th and West 40th] is a highrise office building with 22 floors (height 79 m) in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The building was designed by Charles B. Meyers and built in 1926.” It’s also the first gnomed building on this walk, with 8 gnomes arranged on the stringcourse above the second floor. These gnomes are identical and are sitting ‘Indian-style’ — a favored position for gnomes on buildings — and jotting something onto a pad.

The Parsons School of Design is housed in a nondescript bland box designed by architect William Lescaze on the NW corner of 7th and West 40th. Lescaze has a much more innovative building — his own house — on 211 East 48th, a Moderne building from 1934. The school was founded by painter William Merritt Chase in 1896 as the Chase School; it was renamed in 1936 for longtime president Frank Alvah Parsons, whose Victorian-era St. Mark’s Place home in Staten Island has been highlighted on various ForgottenTours.

1440 Broadway, at the NE corner of West 40th, was constructed in 1925 and was once the broadcast home of WOR Radio. Currently it is the home of the Gannett Co., owner of USA Today (where your webmaster picked up a few $$$ writing an article about Forgotten locations around town that appeared in their Winter 2013 preview issue).

A Standoff

Midblock between 6th and 7th Avenues on West 40th we have a standoff of gnomes, as two gnome-featuring buildings are directly opposite each other. On the south side…

… is 110 West 40th, the World’s Tower Building is a 30-story Gargantua built in 1915. The white terra cotta quatrefoiled peak is a sight to see from 7th Avenue, but we’re here for the four identical gnomes above the 3rd floor, which appear to be sweating and straining to hold up the building. According to the Times’ Christopher Gray (who else!) the developer, Edward W. Browning, originally wanted to drop demonstration bombs (which wouldn’t explode, but you’d have to clear out the block) from airplanes situated on the roof. Because of the final design, though, there wasn’t any room for the planes.

Directly across the street is 119 West 40th, the 22-story 1913 Lewisohn Building, which features 8 completely different gnomes arranged between the windows above the 4th floor. These are formidable gnomes!

The sculptures, dressed in medieval garb, all sit with their ankles crossed under Gothic terra cotta canopies. Each is a detailed allegory – Exploration holds a globe and compass, Industry has a large gear and Learning reads an open book, [Thrift holds a beehive, which must have stung] for instance…

Despite the impressive sculptures, the June 1913 issue of The American Architect was tepid in its assessment of the architecture at best. Comparing it to the 23-story 110-112 West 40th Street Building completed the same year across the street, the journal said the “exterior masonry work…here is buff and, consequently, less striking and quiet in its decorative handling although not unattractive.” Daytonian in Manhattan

The building has been home to Wurlitzer, manufacturer of pianos and organs; United Cigars, a swell as Lorillard Tobacco; and machine manufacturer Manning, Maxwell & Moore. It was once the largest office building by square foot north of 23rd Street.

On the SE corner of 6th Avenue and West 40the is the equally formidable Bryant Park Studios.

Jim Naureckas, in NY Songlines:

This 1901 landmark was designed (as the Beaux Arts Studios) by Charles Alonzo Rich for Colonel Abraham A. Anderson, a gentleman portraitist who had returned from a stay in Paris with that city’s enthusiasm for north light. A great many artists have lived and/or worked here, including photographer Edward Steichen; painters Winslow Homer, William Merritt Chase and Fernand Leger; and print-maker Kurt Seligmann.

On the ground floor is the Park Side Cafe & Market; this used to be the Cafe des Beaux Arts, an opulent ”lobster palace” frequented by musical comedy stars. Owned by the Bustanoby brothers, it featured a ladies’ bar where men could drink only if accompanied by a woman.

Saint Nick

From FNY’s Bryant Park page:

Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) was a Serbian-born inventor, physicist, and mechanical engineer and is widely recognized as the greatest electrical engineer in history. He arrived in NYC in 1884, becoming a citizen in 1891. Tesla developed the basis of modern alternating current (AC) electric systems, pitting him in opposition with Thomas Edison, who championed direct current. Tesla experimented with X-rays and was an early radio pioneer. He founded the Nikola Tesla Company at 8 West 40th Street, on the south side of Bryant Park.

Tesla gained great fame but his last years were not happy ones. He had never married, not paid much attention to his finances and died destitute at the New Yorker Hotel at 8th Avenue and 34th Street, where a memorial plaque was dedicated to him a few years ago. He loved feeding the pigeons in Bryant Park.

This concrete structure on the NE corner has some purpose — it may huse a storeroom or electrical works — and it likely appeared in the 1920s or 1930s, given its Moderne streamlined appearance. Other elements in Bryant Park are Beaux-Arts — the park has many layers of history. The most recent park revamps have added photos of the manicured lawn and tables and chairs.

54-56 West 40th, with massive Doric columns at the entrance, was built as a Republican club in 1901, same year as the Bryant Park Studios. Till recently home to Daytop Village drug rehab center, perhaps a relic of Bryant Park’s bad old days. Daytop went bankrupt in 2012 and sold the building, which was its home since 1973, and will have to find a new home. Unfortunately the new owner would like to tear down the building.

When I had visited Bryant Park previously (see above link) I had noticed the ping pong table on the 42nd Street side, but these tables with popular board games seem to be a new addition. Checkers and Candy Land were set up and a pair were already playing Connect Four. The games seem to be under the honor system, though I’m sure there are hawkeyed obsevers here just in case a miscreant wants to indulge in pilferage.

Games in NYC’s public parks isn’t a novel concept — Central Park has had a Chess and Checkers House since 1952.

Without a doubt, my favorite building on West 40th bordering the park is the chocolate and gold American Radiator Building, a neo-Gothic 23-story skyscraper was designed by Raymond Hood and André Fouilhoux for the American Radiator Company, later renamed the American Standard Building. It features dark brown brickwork and gold leaf on its terra cotta friezes.

My eyes always gravitate to the gold-leafed seminude ladies, among other allegorical figures apparently depicting the transformation of matter into energy, with the brown bricks symbolizing coal. The figures were created by sculptor Rene Paul Chambellan.

In 2001, the building became the Bryant Park Hotel.

At 32 West 40th is the Engineers’ Club Building, constructed in 1907, via a donation from steelman/philanthropist Andrew Carnegie for a social organization for American engineers. This was once the site of the Comstock School for Young Ladies, an organization known as a finishing school.

A nice touch on West 40th between 5th and 6th are the sign stanchions, in black or very dark brown, trimmed with gold leaf, echoic of the American Radiator Building. Even the rails at the subway entrances are tricked out similarly.

A Republican in Manhattan. Paul Fjelde’s 1957 bas relief celebrating FDR’s Republican opponent in the 1940 Presidential race appears on the Bryant Park wall, commemorating the former location at 20 West 40th of the Wendell Willkie Building, demolished for a Republic Bank Building annex.

Wendell Willkie was nominated for president on the Republican ticket in 1940, with backing from the New York Herald Tribune, and earned 45% of the popular vote against FDR. Willkie later went to work for FDR during World War II, serving as a roving ambassador. He remained active in politics — entering the 1944 race despite his collaboration with FDR — and was known for his philanthropy and civil rights activities in his remaining years. He died of a heart attack at 52 in New York in 1944.

The inscription on the plaque reads, “I believe in America because in it we are free – free to choose our government, to speak our minds, to observe our different religions.”

South side of New York Public Library, opened in 1912, and 461 5th Avenue, a snapshot of what was happening with architecture in 1988.

I have a soft spot for the Mid-Manhattan Library, the dumpier cousin of the flagship NYPL across the street, and the more heavily used — it’s the circulating library arm. For a number of years plans have called for the closure of this branch and moving the circulating library into the basement of the lion-guarded library, which would mean moving that building’s stacks elsewhere. Look as if, in 2013, they’re finally going to go ahead with it.

Soft spot? I have given two FNY shows here, each of which has attracted 100 people each.

The Sheppard Knapp carpet dealer ad at #9 East 40th gets more faded every day. The business was at this address from 1923-1926, but had originated on Hudson Street in Greenwich Village in 1863.

#13 East 40th, the Cyprus UN Mission, is a David among Goliaths on this stretch; it probably once had similar buildings adjoining it.

43-story 275 Madison Avenue, at the SE corner of East 40th, is a streamlined building under the influence of Art Deco built in 1930 (Kenneth Franzheim, arch.) It was designated a NYC Landmark in 2009. Here’s a look at the lobby.

Here’s the Landmarks report, but fix yourself some coffee first.

Kodak isn’t dead yet — it has retail presence on the ground floor.

A Building Full of Gnomes

It’s a matter of perspective, I suppose, but the City Review describes 285 Madison, at the NE corner of East 40th, as

an impressively stout though uninteresting 25-story masonry office building erected in 1926 for Isaac Harby and designed by William L. Rouse and Lafayette A. Goldstone.

The building met with tragedy in December 2011 when a woman was killed due to an elevator malfunction. But the building’s happier claim to fame was that for over 75 years, ad giant Young & Rubicam had offices here. For several years I worked at Photo-Lettering on East 45th, the biggest type shop in the city, which provided type for all the ad giants –Y&R, Doyle Dane Bernbach, Ogilvy & Mather, and all the names Mad Men fans heard on the show as rivals of “Sterling Cooper.”

However, we’re here for the gnomes, and there are dozens here, perhaps over a hundred, on the concrete frames surrounding the ground floor windows. They were added as a whimsical touch to brighten things up on what was a fairly tame building otherwise, and as we’ve seen, gnomes were big in the Roaring Twenties. Just about every profession or condition a gnome or gnome-ess could aspire to is represented here — butcher, baker, scientist, philosopher, soldier, mermaid, Indian, priest and many more. Not sure whether this is concrete or limestone, but the elements haven’t been kind to some of them.

While 40th Street west of 5th Avenue is marked by masonry monoliths built in the 1910s and 1920s, when budgets still allowed fillips like carven gnomes on buildings, after the Great War, the world got down to business — after two conflicts that drenched the world in blood, there was no more time for goldfish swallowing contests, raccoon coats, dancing the Charleston and carven gnomes. Politics and architecture got lean and hard, and buildings became angular, forbidding, and intimidating. In the Age of Terror, entering buildings is not even to be thought of unless you actually work there, and even then, admission is given grudgingly. Things relaxed slightly in pop culture during the Swinging Sixties, but even then, our corporate and political masters were tightening the reins almost imperceptibly. But after 2001, the world became an armed camp. The streamlined International Style, seen here in the 1954 National Distillers Building at #91 Park Avenue on the SE corner of East 40th, embodies the paranoid national mood that began after 1945. And I’m not even saying paranoia isn’t the proper reaction.

The Park Avenue motor viaduct carries traffic from the disconnected parts of the avenue separated by Grand Central Terminal and the old Pan Am, now Metropolitan Life Building. It was constructed in 1919, 6 years after the terminal, and the city is now restoring or replacing its light posts with exact copies.

The gleaming black glass 101 Park Avenue on the NE corner was built in 1985 and contains the offices of real estate magnate Peter Kalikow, who at various points in his career has been the head of the Metropolitan Transit Authority and owner of the New York Post. Along with the Grand Central Partnership, which looks out for the great rail terminal 2 blocks away, Kalikow has placed a series of bronze reliefs by sculptor Gregg LeFevre on the sidewalk outside the building honoring other nearby architectural triumphs.

Of course, since New Yorkers are too busy rushing somewhere after the next dollar, no one notices them, except tourists… and Forgotten New York.

The Bedford Hotel, East 40th near Lexington, reminds me a great deal of an apartment building downtown at East 19th Street and Irving Place constructed by George Pelham in 1929-1930. The downtown building is encrusted with pale yellow terra cotta gnomes, and while the Bedford is pretty much gnome-free, the two buildings looks like brothers and it wouldn’t surprise me if Pelham was the architect here as well. If you’re in the suite at the top, you have two fairly substantial gargoyles to gawk at.

Back to masonry buildings on Lexington Avenue, which has maintained an Olde New York vibe between 23rd and 40th Streets. There’s not much information out there about 350 Lexington, on the SW corner of East 40th, except that the building seems to have an ovine, ar at least an ungulate, theme and there are sheep all over it, including a bizarre image of a sheep or deer with a rope around its neck. Somebody tell me the symbolism behind that.

Speaking of ungulates, The Jonathan Allen Stable at 148 East 40th, between Lex and 3rd, was constructed by Charles Hadden in 1871; the horses were stabled downatairs while the ostler or groom stayed upstairs. The building is today used as a veterinary facility and ‘day care’ for dogs and cats. It became a NYC Landmark in 1997. It’s now dwarfed by the Seton Hotel next door.

622 3rd Avenue, a metal and glass box on the NW corner of East 40th, has a 2nd floor atrium deck open to the public, and you can look west on 40th or up and down 3rd Avenue. Undoubtedly it’s busier during the week but I was by on a Saturday.

605 3rd Avenue, between East 39th and 40th, is the corporate home of John Wiley and Sons Publishers, founded in 1807 and specializing in textbooks and technical tomes, as well as the popular “For Dummies” line.

In the East 30s and 40s, high rise apartments overlooking the East River become the rule, such as the Marlborough House at 2nd Avenue and East 40th.

The east side of 1st Avenue between East 38th and 41st Streets has been barren for a few years, waiting for the next big luxury housing project to be approved and built. The towers of Queens West, on the Queens side of the East River, are temporarily visible.

The thicket of high rise apartments in this part of town can look anonymous and interchangeable depending on where you are.

For a few years, the neon Pepsi sign made by Artkraft and installed in Hunters Point in 1936 at a former bottling plant stood alone against the sky without a backdrop, but good things don’t last forever and it will be backdropped by an apartment building soon (as of 2013).

Windsor Tower, at the south end of Tudor City, developed by Fred F. French in the 1920s, replacing the abattoirs and slaughterhouses that formerly were found here. (I plan a Tudor City page somewhere down the line).

Olde English blacklettering is rarely very readable on signage. This one says:

Windsor Tower

Designed, constructed, financed

and managed by the

Fred F. French Companies

For all of Robert Moses’ works, the parkways, expressways, parks and bridges in New York and suburbs that were constructed from the 1920s into the 1960s, there are no roads or buildings named for him within NYC….except for this park and playground hidden away between 1st Avenue, the FDR Drive and East 41st and 42nd Streets.

This small pedestrian walk on the west side of 1st Avenue and 42nd Street is called Trygve Lie (pronounced TRIG-vee LEE) Plaza, after a Norwegian-born Secretary General of the United Nations (from 1946-1952). As a kid I was proud of being able to spell his name correctly on quizzes.

6/17/13