The forecast was frightful one day in late January 2015, when forecasters were mentioning as many as 30 inches, or two and a half feet, of snow. I was skeptical of this, as it hardly ever snows more than a foot and a half at one time in New York — the city is tucked into a harbor and its seaside status, position rather south of where the worst storms hit, and other factors, mitigate against extreme storms. Still, I sensed this might be my last bit of Forgottening for awhile if enough flakes piled up. Thus I grabbed the Lumix and headed off for a fairly short foray onto Bank Street in Greenwich Village.

My instincts were correct and the storm wasn’t nearly as bad as forecast, but it did usher in several weeks of stone cold weather that only let up around mid-March and prevented me from getting out much, as well as an array of pains that 50+ people know about. Fortunately ForgottenNY has a considerable, though not bottomless, backup, and I’m almost never starved for material. I also acquired a cameraphone, so when I see something, I can shoot something. The cameraphone won’t be replacing the Lumix and its 18x zoom for now, though.

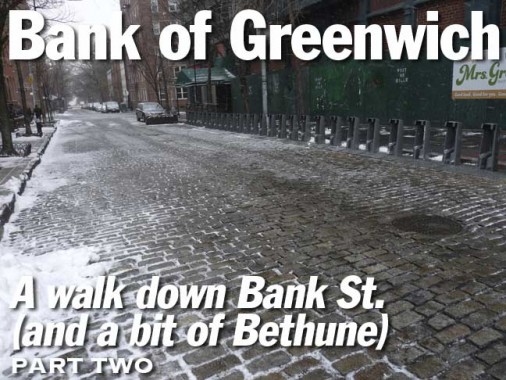

When I left off I had just gotten past the Bleecker Playground, at the X formed by Bleecker Street, Hudson Street and 8th Avenue, which separates Bank Street neatly into two almost identical stretches. As seen in the title card, the pavements of this block of Bank Street between Hudson and Greenwich, as well as the next one between Greenwich and Washington, are Belgian-blocked. Greenwich Village has its share of brick-surfaced streets, which please photographers looking for ambience but cause the teeth of motorists and bicyclists to rattle, especially if they are uneven. Someday, I’ll do a survey of the Village’s brick streets — it’s easier with the Magic of Google Street View. Used to be, major avenues were Belgian-blocked — photos of 2nd Avenue in the 1970s show this.

#92-96 Bank Street (#96, on the corner of Greenwich, is out of the picture) are handsome brickfaced Greek Revival townhouses finished in 1839. In NYC, someone occasionally has the urge to paint their building pink, and #94 is Bank Street’s entry in the genre. #94, though, has retained its original doorway and entrance pediment.

Proceeding across Greenwich Street, #105 and #107 Bank Street are two of a quartet of Greek Revival brick townhouses built in 1846. All but #105 still have their smaller attic windows, and #105’s stoop and a 1st floor window has been removed to provide a basement entrance.

#105 Bank was where John Lennon and Yoko Ono lived for about two years between 1971 and 1973, after a stint at the St. Regis Hotel after Lennon moved to the USA. Lennon was beginning to flex some political muscle during this period, headlining rallies for the jailed Detroit musician/activist John Sinclair, as well as producing an LP for East Village activist David Peel (of “The Pope Smokes Dope” fame). During this time, Lennon and Ono hosted gatherings for Black Panther leaders Bobby Seale, Huey Newton and Rennie Davis. At the time Lennon was coming off the best-selling Imagine LP and single, and while he had no significant radio hits during this time, he did release the LP “Sometime In New York City.” The couple moved to the Dakota apartment building at Central Park West and West 72nd Street in 1973.

The combined #113-115 Bank Street was built in 1857 for carpenter Albert Bogart. Note the stars on the exterior — they are far from mere decorations, as they represent the visible portion of tension road that help keep the walls standing. Decades ago a garage was built on much of the first floor.

Training actors in a specialized school or theater was a new concept when a refugee from Nazi Germany, Herbert Berghof (1909-1990), arrived in NYC in 1939; his HB Studios moved to Bank Street twenty years later and among the studio’s students have been well-known names like Al Pacino, Robert de Niro, Bette Midler, and Christopher Reeve.

Another handsome row of Greek Revival brick residences, #126-130, named by the Greenwich Village Landmarks Commission Report as “perhaps one of the best preserved” of such rows in the city, constructed by a member of the venerable Dyckman family, whose most tangible remnants are the uptown Dyckman Farm building as well as Dyckman Street itself. Most retain original detail, including the eyelet attic windows.

#123 Bank is a four-story warehouse constructed in 1907. In recent decades it was made over into a residential building; I like the projecting bay windows, which allow occupants to look up and down Bank Street.

This relatively small brick residence was constructed in 1855 for a miller, Charles C. Crane. “Designed with handsome simplicity,” according to the LPC.

#132-136 Bank Street are among the oldest in the neighborhood, constructed in 1833. #132 is the best-preserved of the bunch, desoite the addition of a small penthouse.

Looking east on the snowy Bank Street in late January 2015 from near Washington Street. The snow had yet to get heavy (it did later that day) but a predicted 28-32 inches didn’t materialize. NYC settled for ten, but Boston got the full effect.

This is the back end of what was originally a furious manufacturing and entrepreneurial enterprise.

463 West Street, between Bethune and Bank Streets, was built between 1880 and 1900 and was originally the home of Western Electric and later, Bell Laboratories. The vacuum tube, radar, sound movies, and the digital computer were all developed here between 1912 and 1937, and the first TV transmission (a speech by Herbert Hoover) occurred here in October 1927. In July 1922, radio station WEAF (named for Earth, Air and Fire) began broadcasting here; it later became WNBC and, at AM frequency 660, broadcast until October 1988. WFAN has been on 660 since then.

The complex, renamed Westbeth for the streets it borders, was converted to housing in 1969 to provide needed living and studio space for artists who could not afford spiraling rents.

Renowned photographer Diane Arbus, who chose unusual subjects, committed suicide here, July 28, 1971.

There are occasional concerts –in 1997 your webmaster saw Ray Davies here on the Kink kaptain’s autobiographical Storyteller tour.

If the structure in the foreground looks like it could have been an elevated train… it was. I’ll have more on that a bit later.

Inexplicably there’s a small open space on the SE corner of Washington and Bank Street that has room to fit a few parking cars, but apparently only local residents are supposed to access it. Horrible things will happen to unauthorized parkers, except for Parker Lewis, who can’t lose. There had been a gas station here decades before.

The 5-story apartment building on the NE corner contains the bar Automatic Slim’s, which I’ve never been in, but on the ground floor wall is a couple of photos of that elevated railroad I’m not talking about yet, when it was in operation.

The old Western Electric building has a number of lantern-style lamps, outfitted with white mercury bulbs, that help illuminate Bank Street as well as West Street around the corner.

West Street at Bank Street. West has had many guises over the years; at first, it was lined with shipping and ancillary services for most of the 19th and into the 20th Centuries; from 1934 until the mid-1980s it was shrouded by the West Side Elevated Expressway (properly called the Miller Highway after a Manhattan boro president, Julius Miller; and since the 2000s, it has been lined with trees and pedestrian paths, part of the new Hudson River Park.

The NE corner of Bank and West Streets is occupied by one of the shorter buildings in the Westbeth complex, with arched windows on the top floor. This part of the building was, until recently, home to the Brecht Forum, a school distributing Marxist ideas and thought (this is Greenwich Village, after all). The school is now located in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn.

Bethune Street

Bethune Street is the shortest east-west street in the Village, running only three blocks between Hudson and West Streets. It was actually named for a woman, Joanna Graham Bethune, a 19th Century philanthropist/educator on whose land the street was laid out in the very early 19th Century.With the wife of the recently assassinated Alexander Hamilton, she founded the NY Orphan Asylum in 1806.

Heading east again on Bethune you encounter again the ghost tracks at Washington Street, which actually run on the second floor of the Westbeth Building. You may have actually guessed by now that these tracks once belonged to the West Side Freight Elevated, known as the High Line. The tracks once extended south to St. John’s Terminal at Houston Street, but that freight railroad terminal, as well as St. John’s church and Park, were wiped out prior to the construction of the Holland Tunnel.

A few years ago I put together a comprehensive page on this final stretch of the High Line that will likely never be turned into a park.

I was definitely taken by #25 and #27 on the south side of the street, which are some more brick townhouses built in 1836, especially by the unaltered doorways:

| The handsome Greek Revival front door, with ornaments in the panels, has been retained at No. 25 with three-paned sidelights set between paired pilasters. The capitals of the pilasters and of the half-pilasters, set against the reveals of the doorway, are richly decorated with egg and dart moldings, repeated in the molding around the three-paned transom above. The entranceways are surmounted by bracketed lintels which are all distinctly different in design. — Landmarks Protection Commission |

Another significant townhouse grouping on the north side of the street, part of the row between #24 and #34, built in 1846. The building on the right has been recently restored and its brickface repointed. Note again the distinctive doorways on the center and left.

#8 Bethune, in the short block between Greenwich and Hudson. (Some blocks between Greenwich and Hudson and longer than others — Greenwich Street wavers a little and was not built in a straight line; it was originally laid out along the Hudson River shoreline, and the blocks west of it sit on landfill.) This is a former hotel built in the early 1890s, as were the other two buildings on the north side of the block.

Looking thru the complicated intersection of Bethune, Bleecker, Hudson and 8th Avenue toward #75 Bank Street, a Moderne masterpiece discussed in Part One.

The former roadbed of Hudson Street in the intersection is now occupied by the Arthur W. Strickler Triangle, named for a local community advocate in 2009.

The triangle formed by Hudson and West 12th Streets and 8th Avenue is named Abingdon Square. The square is named for the Earl of Abingdon, the son-in- law of Sir Peter Warren, a Royal Navy officer who owned much of the territory in the Village before the Revolutionary War, including the triangle of property now occupied by the square. The square’s statue, dedicated in 1921 for its centennial, was sculpted by Philip Martiny. A former major east-west road in lower Manhattan, predating the grid, was called Abingdon Road.

The statue depicts a World War I “doughboy,” as do many WWI memorial statues around town do, and was a gift from the Jefferson Democratic Club. Martiny sculpted a second such memorial nearby at 9th Avenue and West 28th Street that used the same model!

3/22/15