Glad to be with you this week — for most of the day I began to compose the page it looked like I wouldn’t be able to do it, as a malware virus had taken over some WordPress processes and blocked my ability to upload photos. There are people slaving away in basements and rec rooms whose sole purpose, for some unknown end, is to disrupt people who are trying to make a meager income from web posts. I’ll end my rant there, because I sound all of my 58 years when I rant. As it is, I have little time before my self-imposed Sunday night deadline, so this page will be a bit shorter on average than the rest.

For this trip, I transferred from the J train to the 7 train. The two lines do not have a transfer point at any station — so I had to walk seven or eight miles to make the transfer. After a few weeks trampling about southern and western Staten Island, visiting Prince’s Bay, Travis and Charleston, I was in the mood to travel through more urban scenes and starting in Williamsburg, which has been built up for over a century and a half, fit the bill pretty well.

It’s easy to get to Williamsburg from my home in Little Neck, Queens. I take the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station; the A train to West 4th Street; change for the F and then the J at Essex-Delancey. You can also change for the L at 14th Street, but that’s not going to be a possibility for 1.5 to 3 years as the MTA will be rehabilitating the L train tunnel since it was corroded by Hurricane Sandy in 2012; the storm wrecked the new #1 South Ferry station and severely damaged several tunnels that go underwater between boroughs.

The J is, hands down, the most interesting subway line in the city for old subway car buffs. It still runs some R-42s, shown here, many of whose cars were introduced in 1969; several R-32 cars introduced in 1964; and relatively brand new R-143 cars. Gradually over the next few years, the warhorses will be retired and new blood will take their place. I’ll especially miss the Helvetica roll signs and large bullets in designated line colors; for example, the J and its rush-hour pal, the Z, are the only remaining lines with brown “bullets.”

GOOGLE MAP: WILLIAMSBURG TO SUNNYSIDE

Through the streaked windows of the R42 the domes of Williamsburg can be seen. I’ll discuss this domed, columned bank turned church a little further down.

The Marcy Avenue station on the J, and the large former trolley turnaround beneath it that is now a bus depot are about to become, I predict, one of the major transit hubs in Brooklyn, even though just one subway line serving J, M and Z trains serves the station. The west end of the platform also serves as one of the more popular spots for “railfans” to stand and snap various trains coming off the Williamsburg Bridge. Here, a new-model R-143 (or R-160-A, R-160-B or R-179; I can’t tell them apart) on the M line is about to embark on a bridge crossing.

This domed building was the original branch building of the Williamsburg(h) Savings Bank, constructed between 1870 and 1875 (George Post, arch.) This was the Savings Bank’s headquarters until 1929, when Brooklyn’s only skyscraper was constructed at Hanson and Ashland Places in Fort Greene…so the Williamsburg Savings Bank, now HSBC, has built two of Brooklyn’s signature buildings. Both of these buildings have since been converted to residential use; for many years, the Hanson Place skyscraper contained oral surgical offices I frequented, so I named it the House of Pain.

The train obscures an ad for the Peter Luger steak house on Brooklyn’s Broadway just west of where the el turns onto the bridge. I first visited Peter Luger’s, across the street from the bank, on Christmas Eve in 1993. I had a beer at the bar just inside the door, and saw guys rushing about carrying around plates stacked with raw steaks. This was the place for me, I immediately thought, though it was until 2000 that three companions and I finally got in. What you have to remember is that they have their own unique way of doing things there, and you have to let the waiters do things their way, but when the steak came we set on it like four jackals on a wildebeest carcass. The huge porterhouse steak, always cooked rare at Luger’s, was gone in about fifteen minutes. I’ve only been in twice and would like to go again sometime.

It’s interesting that the phrase “TO LET”, as in “for rent”, seems to have passed out of English completely. “Let,” in this sense, and “lease” have the same roots in French and before that, Latin and the Indo-European root languages that preceded it. This one is on Havemeyer Street between Broadway and South 5th, and is considerably set back from the street; clearly, it’s meant to be seen mainly from the Marcy Avenue elevated platform serving the J and M trains.

It’s set to fade completely in the next decade; I can’t make out the top line, and the bottom simply says SUPT. [superintendent] ON PREMISES.

In 1965 the phrase was still popular enough for Roger Miller to include it in “King of the Road”:

“Trailers for sale or rent.

Rooms to let, fifty-cents.”

I have mentioned that the J/Z lines are the last repository of several ancient subway car designs. This is the R-32, used infrequently on the J, but still makes up a large part of the C train fleet serving 8th Avenue in Manhattan and Fulton Street/Pitkin Avenue in Brooklyn. This model, noted for its stainless steel, corrugated exterior (and meat locker air conditioning in the summer) was first introduced in 1964, the same year the Beatles and the Stones and the NYC World’s Fair were introduced in the USA. To me, the only drawback is the longitudinal seating, but window-faced seats are only on the R-46 and R-68 cars these days, which will likely be phased out by the end of the 2010s.

I alighted on Broadway from the Marcy Ave. platform. Descending on the stairs, I was met by some unique sidewalk signage right off the bat, from what I imagine is terra cotta on the El Emperador Elias restaurant sign. From a Yelp review we learn that the name “is likely a reference to an early Franciscan who eventually defected to the Holy Roman Emperor and was excommunicated by Pope Gregory.” From the reviews, it’s a comfort food place I should try out. The shoe repair sign bears the signs of having been here for decades, perhaps the 60s or 70s.

Somewhere along the way I had discovered that Laska’s, for which these brilliant mosaics at the entrances at 270 Broadway were made and are still preserved after 60 or 70 years perhaps, was a florist, but no such documentation exists on the world wide web these days. Broadway in this stretch used to feature even more ancient signage, which I showed off on this FNY page that documented the first Forgotten New York tour on June 1st, 1999.

Storefront at Broadway near Roebling Street, named for the father-son team, John and Washington Roebling, who engineered the Brooklyn Bridge. I can make out the word “Wright” and there is also a large word in the brown-colored field beneath it.

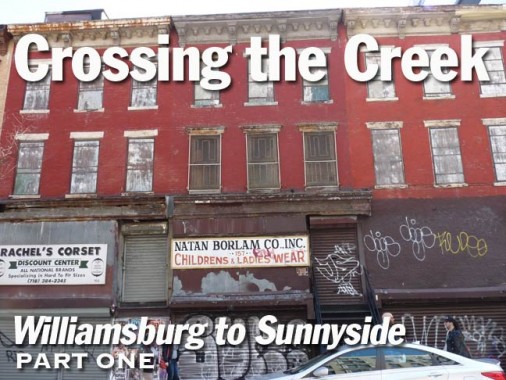

Broadway bisects Williamsburg’s south side which is an interesting mix, demographically, of Eastern European Jews and Hispanics and the “look” changes from block to block. Along Broadway several businesses were shuttered on Saturday, such as this hat shop.

As we’ll see, the immediate area is a Forgotten NY favorite as there are plenty of ancient signs, as well as abandoned lamppost designs, to be taken in.

This painted sign greets J/M/Z train riders coming southeast.

The large space under the el ramp onto the Williamsburg Bridge (which still has some very old railings which may be originals from the early 1900s) once served ten Brooklyn streetcar lines. Today, the B24, B32, B39, B62, B60, Q54, and Q59 buses all stop or originate here.

New davit and double-davit style lampposts are being installed in the bus terminal and even a few “dwarf” davits have appeared on Broadway. The lamps employ Leotek Green Cobra LED lamps. These are still relatively rare in Brooklyn, which has mostly been switched to VRDN LEDs from Eaton.

One relic from streetlighting of the past is still found on one of the el pillars, an incandescent design that once lit NYC’s side streets by the thousands. There are three or four extant remains of this style; others can be found on an “exit ramp to nowhere” at the Henry Hudson Parkway and West 72nd street, where a few West Side Highway lamps have been left in place.

It should also be noted that Roebling Street, Division Avenue and other selected Williamsburg streets south of the bridge received their own peculiar streetlamp designs in the early 1970s, many of which survive like this number on Roebling near Broadway. I discuss these lamps in a little more detail on this FNY page.

This ancient edifice, which never seems to have had any exterior renovation done at all, is home to storefronts on the ground floor and offices on the top floors. I’d like to know what’s behind the large windowpanes on the second floor. Note the slight curve, as this is where Broadway meets South 8th Street.

At this point, a small section of the old Broadway Ferry spur can still be seen west of the Marcy Avenue station. The entire spur was demolished in 1940, opening a four-block section of Broadway to the sun, the only part of Brooklyn’s Broadway that can claim sunshine. It had stops at Driggs Avenue and Broadway Ferry at Kent Avenue; the ferry is long-vanished. There’s a section of trestle coming off the bridge on its way to Broadway that appears as if it were unchanged, except for various paint jobs, from when it was originally built.

Heading north up Havemeyer Street, named for one member or the other of the 19th Century German immigrant Havemeyer family. You can take your pick which one — brothers Frederick C. and William, who opened a sugar refinery in Manhattan; Frederick C. Jr., who opened another sugar factory in Williamsburg; William F., who became a 3-term NYC mayor; F.C. Jr.’s son Henry, who renamed the sugar factory Domino and came to dominate the market. There is also a Havemeyer Avenue in Castle Hill in the Bronx; many northern Bronx avenues are named for NYC mayors.

According to local legend, when the Domino sugar refinery at Kent Avenue and Grand Street was working, the smell of caramelized sugar could be sniffed in the immediate vicinity. The plant, instantly recognizable from the J train on the Williamsburg Bridge or from boat traffic in the East River by its huge illuminated sign, shut down in early 2004 after about 150 years in business, putting 200 employees out of work. American Sugar Refining Company officials said the Brooklyn plant was not equipped to compete with its plants in Baltimore, Yonkers, N.Y., and outside New Orleans. The red neon Domino sign will be retained, but the plant itself will now be the centerpiece of a luxury housing development. It’s on the waterfront, meaning any housing built there will be out of the price range of any former Domino plant workers.

Here’s an ancient plastic-lettered sign on Havemeyer between Broadway and South 5th. A trousseau is a wedding dress.

The Dime Savings Bank of Brooklyn was founded in 1864 and, a pair of its distinctive Brooklyn bank buildings still stand. The first is the domed Dime Savings Bank, an Ionic-columned neo-Classical palace built at Albee Square, DeKalb Avenue and Fulton Street downtown between 1906 and 1908 by architects Mowbray and Uffinger. The interior is one of Brooklyn’s most magnificent indoor spaces: the central dome is defined indoors by a ring of twelve marble Corinthian columns crowned, at the top, by gilded representations of the obverse and reverse of the “Mercury” Dime. However, that bank is no longer owned by Dime and has passed through several banks, presently Chase.

What we see here is the Dime’s other great Brooklyn bank building at Havemeyer and South 5th, facing toward the Williamsburg Bridge. It moved into this Corinthian-columned building with a huge pediment and clock in 1908. There are 25 extant branches of Dime remaining. Note Williamsburgh spelled with the h, which was loped off sometime in the early 20th Century. Other locales, such as Pittsburgh and Plattsburgh, have kept their h’s. I think the longer -burg names tend to lose their h’s.

Next door on Havemeyer is the Ortiz Funeral Home, which boasts a pair of classic neon signs, one on the top floor and this one, overhanging the sidewalk. This is actually one of a chain of R.G. Ortiz funeral homes, as there are also a number of branches in Manhattan and the Bronx; this is the only one in Brooklyn.

At Roebling Street between South 4th and 5th is Continental Army Plaza, first designed in 1903, the year the Williamsburg Bridge opened. The centerpiece of the plaza is Henry Shrady’s 1906 equestrian statue of George Washington that depicts him at Valley Forge: cold and weary, yet determined. Shrady later created other major public monuments including the Grant Memorial at the foot of the Capital Grounds in Washington, D.C., and the Robert E. Lee equestrian statue in Charlottesville, Virginia. The Works Progress Administration renovated the plaza in 1936 to roughly the form it is seen in today.

The Continental Army was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in their revolt against the rule of Great Britain. The Continental Army was supplemented by local militias and troops that remained under control of the individual states or were otherwise independent. General George Washington was the commander-in-chief of the army throughout the war.

Most of the Continental Army was disbanded in 1783 after the Treaty of Paris ended the war. The 1st and 2nd Regiments went on to form the nucleus of the Legion of the United States in 1792 under General Anthony Wayne. This became the foundation of the United States Army in 1796. wikipedia

Backgammon table in Continental Army Plaza

The plaza also has a clutch of unique lampposts. I am unsure if these are renovated originals or new posts from a later park refurbishing.

The piece de resistance of the plaza is the current Ukrainian Autocephalic Orthodox Church in Exile (now called the Holy Trinity Cathedral), originally the Williamsburg Trust Company, built in 1905 by Helmle & Huberty; its whiteness dazzles as if it’s cleaned daily with Pepsodent. The firm also designed the Prospect Park Boathouse and the McGolrick Park Shelter Pavilion in Greenpoint.

Exterior signs on the church are in Ukrainian and English.

Emblematic sculptures in marble depict a spade and a staff entwined by two serpents. I’m stumped as to what the spade represents, but the staff/snake symbol is associated with Hermes, the Greek messenger god (the Romans called him Mercurius) and it was generally found on commercial buildings from the 18th and early 19th Centuries. It was also used as a symbol for speed — a caduceus can be found on remaining stations or overpasses of the NY, Westchester and Boston Railroad in the Bronx, much of which is now the Dyre Avenue line (#5 train).

It’s a commonly made mistake equating the caduceus with the medical profession. In medicine the symbol is the Rod of Asclepius, which has one entwined snake, not two.

Another sculpture shows a pair of swords bundled with fasces, a symbol first used by the Etruscans, people from the Italy conquered by the Roman Empire; the Romans adopted fasces, wooden staves bound most frequently around an ax but here, a sword, as a symbol of governmental power. They were used as motifs in Classical architecture well into the 20th Century and even wound up on the back of the “Mercury” dime between 1916 and 1945. In the center is depicted a woman holding scales associated with fair dealings with the Latin phrase Nos progredi mur, “We move forward.” Note again, Williamsburgh with the h.

The pedestrian/bike path on the north side of the Williamsburg Bridge begins here. If you have to choose between bicycling and walking I’d advise the bike. It’s a very long distance for walking, especially on the Manhattan side which has a very lengthy ramp between Delancey and Clinton Streets and the actual bridge.

Or, you can simply walk back to Marcy Avenue and take the J or M train…

Because of the late start, I’ll keep it short and sweet this week. In Part 2…up Havemeyer Street

5/15/16