Well-plumbed NYC territory for Forgotten NY, I realize, but it was time for my annual winter or early spring pilgrimage to Nathan’s in Coney Island. I have joined the Polar Bears on January 1st; I have had my two dogs, fries and Coke on a 65-degree Christmas Day; and I have enjoyed the first rays of spring on the Boardwalk Nathan’s on mild March days. This time I visited in mid-March and while latter February was quite mild, March had been quite leonine with the thermometer in the 20s, the wind howling, a recent light snowfall on the ground and a blizzard predicted (we got a good snow and sleet storm, but the blizzard missed). Nathan’s was busy, though not packed and jammed as it is during the summer peak, which is why I go in the cold months, though I have concluded tours here in the summer.

After I had my fill, I braved the cold wind, walking around Coney for a spell before going north to check out some Gravesend sites where I hadn’t been for awhile…

GOOGLE MAP: CONEY ISLAND and GRAVESEND

One of the most striking subway transformations of my lifetime was the conversion of the Coney Island Terminal from a rundown, shabby embarrassment (that nonetheless had plenty of leftover historic material left in it) to a state of the art modern hub that nonetheless has a design that harks back to those European train sheds you see in the movies (none of which comes to mind at the moment; help me out here in Comments). The entire terminal was broken down and rebuilt during the early 2000s.

For a look at the old Stillwell Avenue terminal, see this FNY page.

Nathan’s, founded by Polish immigrant Nathan Handwerker, a former employee of Charles Feltman (the original hot dog purveyor of Coney Island) in 1916 at the encouragement of singing waiters Eddie Cantor and Jimmy Durante, has held down the corner of Surf and Stillwell for 101 years (as of 2017), as well as a more recent boardwalk establishment, and has opened hundreds of chain locations in the USA, Europe and Asia; however, the Handwerker family sold their holdings in 1987.

Coney is a perennial draw year round. The Coney Island Polar Bear Club was founded in 1903, but only in the last twenty years or so has it reached true public consciousness. Members take an annual New Year’s Day plunge into the Atlantic Ocean at Coney Island. By 2005, there were 300 participants and 6000 onlookers. Members have special dispensation to swim in the Atlantic while the beach is otherwise closed each Sunday from November through April; the beach is open to all while lifeguards are present between Memorial and Labor Days.

Riegelmann Boardwalk, looking west from Schweickerts Walk, Sunday, March 12. Prominent is the Parachute Jump Tower, which is no longer an active ride, but has been landmarked and is a universal symbol of Coney Island — even though it was originally installed at the 1939-40 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows as a Life Savers-sponsored attraction. On the right is the entrance to the New Thunderbolt roller coaster, a 2014 replacement for the original 1925 ride that was built atop the Kensington Hotel — which remained in place as a private residence for many years and inspired scenes in Woody Allen’s 1977 classic film, Annie Hall.

No one except the Department of Transportation calls the Coney Island boardwalk the (Edward) Riegelmann Boardwalk, but since its opening in the 1920s it has indeed been named for the Brooklyn Borough President (1869-1941) who championed its construction. During his tenure from 1918 to 1924, Riegelmann also presided over the expansions of Kings Highway and Linden Boulevard as a response to the rise of automobile traffic.

Coney Island’s Bowery (until recently called Bowery Street on DOT street signs) is a quiet pedestrian walkway at least in the off season, but in the early to mid 20th Century it was quite raucous indeed:

The most famous section of West Brighton was an area known as the Bowery. The Bowery was south of Surf Avenue and extended from Jones Walk, on the west side of Feltman’s, to West 16th Street, on the east side of Steeplechase Park. Its main drag, known as Ocean Avenue until around 1905 and as Bowery Lane thereafter, ran parallel to Surf Ocean and about 65 yards south of it. The Tilyou and Stratton families had leases to much of the land, and they are believed to have originally constructed a boardwalk along this lane, which was later replaced by a paved walk. The original name of Ocean Avenue must have led to some confusion in the Postal Service as there was another Ocean Avenue in nearby Sheepshead Bay.

The Bowery was a raucous area where police frequently looked the other way as drinking, gambling, music and shows took place well into the night. Coney Island’s appeal was that anyone could find the type of experience they desired. For those looking for more variety and fun, and less refinement, the Bowery stood head and shoulders above Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. [Heart of Coney Island]

On Bowery Street between Stillwell and West 15th, I was amazed to find several large-scale art pieces arranged on walls. They are part of a project called Coney Art Walls, co-curated by developer Joseph Sitt, who bought up several Coney Island properties in 2001; for a time, it was feared that Coney Island would be home to multi-story condo towers, but those fears were alleviated when Sitt sold most of his Coney properties in 2009.

The wall above, by the Thrill Collective and Chris “Daze” Ellis, depicts a mermaid-tailed version of the old Spookerama Cyclops, the symbol of a former 1950s Coney thrill ride.

Marie Roberts is the dean of Coney Island muralists; her work adorns the Coney Island Museum and Freak Show, both housed in a former Childs restaurant at Surf Avenue and West 12th Street. The poster depicts Granville T. Woods, an African American inventor known as the Black Edison; he invented the ‘third rail’ used to conduct electricity in transit systems and made improvements to the telegraph, among other inventions. Woods demonstrated two of his inventions in Coney Island, an electric railway and an electric roller coaster called the Figure Eight. Also shown is one of Coney Island’s bizarrest, yet useful, sideshow attractions, Dr. Martin Couney’s Baby Incubator exhibit, which nursed premature infants to health. Today, such an exhibit wouldn’t pass propriety muster, but decades ago, the sideshow begat techniques used in hospitals for decades after.

Art by D*Face a.k.a Dean Stockton

Mermaid tales by Thrive Collective for Schools

How many comic book icons can you recognize in this mural by Crash? Captain America’s fist, Betty of the Archie books, Superman’s S, and the thunderbolt logo of The Flash.

Spot the mermaids in this mural by Nina Chanel Abney.

A sailor has rescued yet another mermaid in this mural by Aiko. It portrays a Japanese folk tale:

“Taro Urashima and Dragon Palace” is a very popular Japanese tale from the 7th century. One day a fisherman named Taro rescues a turtle on the beach. He is rewarded for this with a visit to the dragon god’s palace under the deep sea to meet the princess. He stays there for three days and has the most amazing time partying with beautiful ladies. Upon his return to his village, he finds himself 300 years in the future …

I translated this story into two versions on the double-sided wall for Coney Art Walls 2016. On one side “Handsome Brother and Mermaid” is a story about the sailor man in modern times rescuing the mermaid princess and taking her back to Dragon Palace. One the other side, “The Other World” portrays sexy princesses and the dragon god living in the palace, seducing Brooklyn’s audience to very exotic and mysterious world.

Mechanical mermaids are featured in this mural by the British London Police.

I’ve recognized street art by How and Nosm (Raoul and Davide Perre) on Fillmore Place in Williamsburg. Their pieces are among the more recognizable ones in the street art demimonde.

Yet one more gorgeous mermaid and the classic Pepsi-Cola logo are featured on the Stillwell Avenue side of Tom’s Coney Island, which replaced the old Cha-Cha’s music venue (see here on a Coney Island page I wrote some years back) a few years ago.

Retro versions of Type 24 Twinlamps came to the Coney Island Riegelmann Boardwalk about 15 years ago. They replaced octagonal posts with cobra neck masts that had, in turn, replaced earlier versions of Twins that could be found only on the boardwalk.

Just across Schweickerts Walk from Nathan’s on the south side of Surf Avenue is another Coney Island veteran, Williams Candy and, like Nathan’s, it stays open all winter to slake the needs of candy apple and cotton candy addicts. (During a Christmas visit to Uncle Bacala’s restaurant in New Hyde Park, I was clued in on their cotton candy tradition, but didn’t partake.) The candy store has been a Coney tradition for nearly 80 years; it was completely rebuilt after damage by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Across Surf Avenue, I checked on the remains of the long-gone Seven Seas restaurant on the SW corner of West 16th Street. Only three letters from its West 16th Street sidewalk inlay sign remain; the inlay sign on Surf Avenue was paved over a few years ago. The space has been a parking lot for decades now. Both signs can be seen on my Surf Avenue page written in 2012.

Neptune Avenue, named for the Roman god of the sea (the equivalent of the Greeks’ Poseidon) runs from Shore Boulevard and Emmons Avenue at the west end of Sheepshead Bay west into Sea Gate, where it ends a block away from Norton’s Point at a curving Surf Avenue in the top secret gated community. I must admit, I’ve never biked or walked its western stretch west of Cropsey Avenue, since it’s fairly mundane architecturally except for the Coney Island Creek pumping station on West 23rd Street, which is up for Landmarking, so far unsuccessfully.

I checked on Totonno’s Pizza, which, as the sign says, has been in business here on Neptune Avenue off West 16th Street since 1924, when it was founded by Antonio “Totonno” Pero, a former employee at Lombardi’s, one of New York City’s very first pizzerias. It’s among the best known purveyors of coal-fired brick oven pizza in the city. I was happy to see it had received a new building front. Only the day’s 25-degree weather probably prevented the lines outside the building from forming, as most of the tables are filled on an average weekend day.

Totonno’s is in a stretch of Neptune Avenue populated mostly by auto repair, auto glass and flat fix shops, but there is the occasional diner like Pop’s as well as the odd deli with an interesting name.

A pair of interesting Neptune Avenue murals for a clothing store and one of the many auto repair palaces.

Riviera Caterers, Stillwell and Neptune Avenues, isn’t anything to write home to Mother about on the exterior, but it gets nearly uniformly good Yelp ratings as a wedding reception venue.

Just past the elevated trestle carrying Sea Beach (N) and West End (D) trains over Neptune Avenue, the Luna Park Houses are in view, as is a mini-mall serving their residents. The original Luna Park for which they are named was a truly wondrous amusement park opened by Frederick Thompson and Elmer Dundy in 1903; thousands of electric lamps lit up the park in an era when lightbulbs were still brand new. The park lasted until 1944 when it was destroyed by a series of fires. Notoriously, Topsy the Elephant was electrocuted at the park to prove that alternating current was superior to the competing direct current; Thomas Edison’s involvement in the incident has been mostly disproved. A new Luna Park was opened in 2010.

Coney Island Creek nudges near Neptune Avenue (nice alliteration) in the West 20 streets and again here, east of Stillwell Avenue. The north side of the avenue has long been a no-man’s interregnum, but I noticed a new deli serving the flat fix, car upholstery and wheel alignment palaces found there.

One of Coney Island Cree’s weirder features is a rusted yellow submarine built in 1970 to explore the remnants of the sunken ocean liner, the Andrea Doria. Tide and Current Taxi‘s Marie Lorenz, artist/explorer Duke Riley, and ForgottenFan “Movie” Mike Olshan explored the Creek for this FNY segment.

As the trestle carrying the Culver Line elevated train (F), over Neptune Avenue, the Amalgamated Dr. James Peter Warbasse Houses loom up in the background. The co-op apartments were built by United Housing Foundation and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union between 1960 and 1964.

The Fate of Neptune Avenue

Take a look at this except I made from the 1929 Belcher-Hyde desk atlas of the area. In those days thre were only a handful of paved roads in the area, and they were home to transit and streetcar lines: Neptune Avenue, West 6th Street, the partially-vanished Sheepshead Bay Road, and the vanished Triton Avenue and Cortland Street, which faced a trolley barn. Neptune Avenue ended its eastern progress at West 6th, and took over the course of Triton Avenue at Cortland.

Shell Road, now a major thoroughfare, had existed in some form since Coney Island’s early days. From FNY’s Shell Road page:

Shell Road first appears in 1829, when the Coney Island Road and Bridge Company built a toll road spanning the strait separating mainland Gravesend from Coney Island, which was actually an island in that era. The road led to the first Kings County seaside resort, Coney Island House; it may have been paved with oyster shells. Luminaries like Washington Irving and Walt Whitman stayed at the resort.

In 1929 its course seemed likely for elimination and several unbuilt houses are shown where its future course would ultimately run.

Sheepshead Bay Road

As mentioned in FNY’s 2017 Sheepshead Bay-Dead Horse Bay page, there are two separate Sheepshead Bay Roads, a short one running between Neptune Avenue and West 6th and another one, several blocks east running from East 12th and Gravesend Neck Road southeast to Emmons Avenue. In the dim past the two roads were continuous, with the missing section running along the northern end of the vanished Brighton Beach Race Course, one of three lost racetracks in Sheepshead Bay and Brighton Beach. After the Brighton Beach Race Course vanished, streets were laid out and dwellings built in the Roaring Twenties in what is now the heart of Brighton Beach east of Ocean Parkway.

Just before running under the Culver el, an unmarked road angles southeast from Neptune and runs as far as West 6th, where its only identifying street sign appears. This is the orphaned western segment of Sheepshead Bay Road, which is apparent from a look at the 1929 map shown above. Chances are few cabbies or Uber drivers are confused by this, as no addresses or buildings front on it.

I’ve always been a little fascinated by the simple brick St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, which is only 50+ years old as it was built at Neptune Avenue and West 8th Street in 1966. It was pretty new when I first encountered the area by bike at age 11 in 1968! The roof shows some damage, probably committed by Hurricane Sandy. As it turns out it’s one of the oldest Protestant congregations in Coney Island, instituted in 1875 and its original location nearby on Neptune Avenue was popular with bicyclists who would attend Sunday services! (I’ll touch on bicycles a bit later.) The congregation had a Gothic-style edifice on West 5th Street from 1926 into the Sixties, but it was condemned when the co-ops and housing projects were built, and the simple brick structure known today was erected.

McDonalds, Neptune Avenue and West 6th. In January 2017 I saw The Founder, about McDonalds chief executive Ray Kroc, and was impressed and horrified to see how he popularized the fast-food chain and then wrested the company away from its actual founders, the McDonald brothers.

This particular branch features a unique construction, as it diverges from the usual McDonalds NYC template, incorporating the Golden Arches into the superstructure. Most notably, the signage features original McDonalds spokeschef Speedee, who had been replaced by Ronald McDonald in the 1962. Only a handful of McDonalds restaurants nationwide still feature him.

When I saw this sign at Neptune Avenue and West 6th, I thought I recognized the name. Lasher (1944-2007) was a prominent figure in Brooklyn politics from 1973 to 2001, serving in the NY State Assembly and NYC City Council. He helped fund Coney Island area recreational facilities such as the Brighton Playground and Calvert Vaux Park.

The Culver El trestle over West 6th Street. The southern stretch of the Culver El opened in May 1919, replacing an at-grade steam railroad that had been instituted by entrepreneur Andrew Culver in 1875.

I had a keen interest in the Culver El in this stretch, as well as the elevated on the east side of Stillwell Avenue between Neptune and Surf Avenues when I was bicycling Brooklyn in the 1970s and 1980s. Why? The reason was simple. Well into the 1980s, both stretches still used incandescent Westinghouse AK-10 lamps, as well as the occasional Bell and Gumball, appended to the overhead trestles. In fact the northern stretch of West 6th Street between the Belt Parkway and the Neptune Avenue el station still had incandescent Gumballs in scrolled masts on telephone poles (some of which can be seen here) when I first encountered this stretch on my bike in 1968! It was a lamppost historian’s treasure trove. Of course I wasn’t carrying a camera in those years, so no record exists. The pendant lamps were changed to yellow sodium “buckets” in the early 1980s and later to tube box lights in the 2000s.

The “Neptune Avenue” station is located about midway between the Belt Parkway and Neptune Avenue, so the name sort of doesn’t make much sense. However, in one of the MTA’s longest-running anachronisms, the station used to be named “Van Sicklen” (it could have been Van Siclen without the K). Brooklyn has a number of streets named Van Sic(k)len, but none of them around here. The reason for the station name was the long-disappeared Van Sicklen Hotel, where the Culver steam line had a stop. The station was renamed in the 1990s.

It was also renamed to avoid confusion with the Van Siclen Avenue station on the #3 train above Livonia Avenue, the Van Siclen Avenue station on the Fulton Street el (J) and another Van Siclen Avenue station on the IND C train on Pitkin Avenue. That’s a lot of Van Sic(k)len stations!

The remnants of Triton Avenue, a curb cut and a walkway through the Warbasse Houses, can be seen beneath the Neptune Avenue station. Several years ago I found some porcelain Triton avenue street signs on a Shell Road lamppost, but they’ve long disappeared.

In a way my Triton Avenue discovery in 1968 sowed seeds for Forgotten NY. I explain why on this FNY page.

The Circumferential (soon changed to Belt) Parkway was constructed from 1939-1940 and forms a ring or “belt” in the city limits ringing Brooklyn and Queens, consisting of Shore Parkway, Laurelton Parkway, and the Cross Island Parkway.

Here the Belt Parkway runs beneath the older Culver El structure. I’m not sure how it was done: was there always enough room to run Shell Road, a truck route, beneath the Belt, or did the el have to be jacked up to permit the Belt to be constructed beneath it? If you know, answer in Comments below.

There’s a small warren of one-block streets between Shell Road and West 3rd Street between the Belt Parkway and Avenue X, all of which begin with A, B, C or D; indeed, three of them seem to all use the letters B, C, D and K: Bouck, Dank, Bokee and Cobeck; there’s also Atwater and Colby.

Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss explain two of them in Brooklyn By Name: William C. Bouck (1786-1859) was Brooklyn’s canal commissioner and the street is laid out near the former Gravesend Ship Canal, which connected Coney Island Creek and Sheepshead Bay. Bainbridge Colby (1869-1950) was secretary of state under President Woodrow Wilson and was later a fervid opponent of the Soviet Union.

(I think both these explanations are somewhat of a stretch, and the authors are silent on the other somewhat soundalike street names.) All appear on street maps by the mid-1930s.

Bouck Court has a little secret. It’s home to Shell Lanes, one of a diminishing number of standalone bowling alleys in the five boroughs. I estimate there’s about two dozen left in NYC; there may have been more than a hundred at one time. It’s unusually constructed because when you walk in the check in desk is to your left and the lanes are on both sides.

I bowled off and on between 1967 and the early 1980s, belonging to a number of leagues. I bowled mostly at Leemark (Bay Ridge), Rainbow (Gerritsen Beach) and Diplomat (Flatbush) and in 1975 belonged to a college league that rolled at Bowlmor on University Place in the Village, long before it became a nightclub/bowling alley. My first two games at age 9 were a 6 and a 7 — at first I couldn’t bowl my age! My average never got much above 150 because I never mastered a hook; I’d just heave it down the middle and pray. You know how weekend duffers throw their clubs when they hit a sand trap? You can’t do that with a bowling ball.

One of my favorite subway spots in NYC isn’t part of a subway station at all; it’s the chalet-like entrance to the Coney Island Yards on Shell Road. Periodically, the yard facility opens up for Transit Museum tours. Is the office open for public viewing on those tours? I say that because looking through the door, I glimpsed some colorful stained glass lit up by sunrays. I would have loved to open the door and check it out, but no doubt I would have gotten the bum’s rush.

At the parking lot entrance we have what look like two IND-design lamp stanchions. In fact the entire station entrance may date to the IND era, 1930-1950, and if the IND had ever built at-grade or elevated stations we might have gotten more architecture that looked like this.

Turning left around the corner on Avenue X, we find a one-block street ending at West 7th Street called Boynton Place. It’s fairly nondescript with par for the course housing, but the street is named for Eben Moody Boynton, who in the 1890s tried and failed to institute a different kind of mass transit: the bicycle railroad. I explain the whole thing on my Shell Road page.

Lake Place runs in two sections in Gravesend, one between West 8th and West 11th Street and another between Van Sicklen Street (that name again) and West 7th. Currently reduced to a semiprivate driveway, it was once one of Gravesend’s major highways. See this FNY page for details.

Some original stained glass transom work on this house at #2127 West 7th Street.

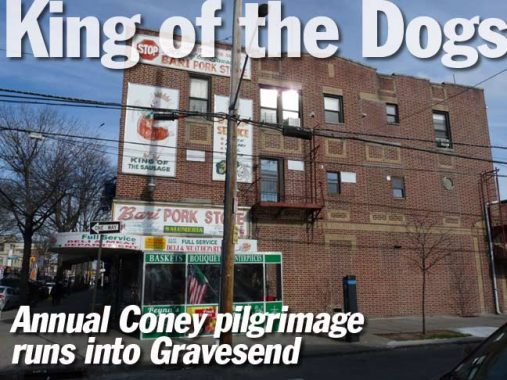

On Ave. U and West 7th is the magnificent Bari delicatessen (“pork store”) which contains spectacular animal cannibal painted signage of a slavering, crown-wearing swine, the personification of the “king of the sausage” tag, holding a string of intestine-encased prepared pork. Bari, also the name of a kitchen supplies wholesaler on the Bowery, is named for a southeastern Italian city on the Adriatic Sea.

More from Avenue U on this FNY page.

Heading east on Avenue T, here’s a spectacular Catholic church complex at Van Sicklen Street (that name again), Sts, Simon and Jude Church, named for two of the more obscurer apostles. Indeed, one of British author Thomas Hardy’s novels is called Jude the Obscure.

Jude is so named by Luke and Acts. Matthew and Mark call him Thaddeus. He is not mentioned elsewhere in the Gospels, except, of course, where all the apostles are mentioned. Scholars hold that he is not the author of the Letter of Jude. Actually, Jude had the same name as Judas Iscariot. Evidently because of the disgrace of that name, it was shortened to “Jude” in English.

Simon is mentioned on all four lists of the apostles. On two of them he is called “the Zealot.” The Zealots were a Jewish sect that represented an extreme of Jewish nationalism. For them, the messianic promise of the Old Testament meant that the Jews were to be a free and independent nation. God alone was their king, and any payment of taxes to the Romans—the very domination of the Romans—was a blasphemy against God. No doubt some of the Zealots were the spiritual heirs of the Maccabees, carrying on their ideals of religion and independence. But many were the counterparts of modern terrorists. They raided and killed, attacking both foreigners and “collaborating” Jews. They were chiefly responsible for the rebellion against Rome which ended in the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. [Franciscan Media]

The parish has been in existence since 1897, while the current building is a modern design I estimate to have been built in the 1960s; correct me if I’m wrong in Comments. The elementary school building on the south side of Avenue T closed several years ago, with the building now occupied by Coney Island Prep High School.

Many Catholic parishes build mini-towns, with churches, schools, rectories and parish houses; Sts. Simon & Jude was no exception.

Just north of Avenue T on McDonald Avenue is the Samuel Hubbard House, built about 1750, most likely by the Johnson family (an extinct roadway in Gravesend was called Johnson’s Lane). The two-story wing, at the left side of the picture, was added in 1925.

When I first went past the Hubbard house in 1999, it was pretty much in ruin. Fortunately it was purchased by John Antonides, who rebuilt and restored the building. Its previous resident, who was a member of the Hubbard family, had spent most of her life in the house for a total of over 90 years.

Time to kick it in the head once again. Only the northbound stations on the Culver are operating in early 2017, as most southbound stations are undergoing complete rebuilds. When that work is finished, work on the northbound stations will commence. Similar mishigoss is happening on the Sea Beach (N train).

Heaters are provided in the foyers of many elevated stations. In the Manhattan els’ glory days before the Fab Forties, elevated stations frequently featured pot belly stoves!

“Comment…as you see fit” in Comments below.

3/19/17