By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

On a recent stint in jury duty I had the opportunity to appreciate the detailed lobby mosaic in the otherwise understated Queens County Courthouse. I previously wrote that Jamaica appears as the logical county seat for Queens, but with the Criminal Court and Borough Hall a mile to the west, Kew Gardens is the de facto seat of borough-related governmental activity. Exiting the Kew Gardens-Union Turnpike subway station, one is greeted by an ornate empty pedestal where Triumph of Civic Virtue stood from May 29, 1941 to December 15, 2012. Designed by Frederick William MacMonnies, its depiction of a heroic nude man standing atop two female demons representing corruption and vice, ensnared in their own nets. Angelina Crane gave funds for its completion but from the start women’s groups have been protesting its existence.

Initially located in City Hall Park, it was exiled to Queens by Mayor LaGuardia, where it was left to crumble. At its present location in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery the dead can’t protest its presence. MacMonnies and Crane are buried nearby. There was talk of building a women’s themed monument here but nothing further has been publicized on this proposal. Kevin Walsh wrote about this monument in 2008 and shortly before its removal in 2012.

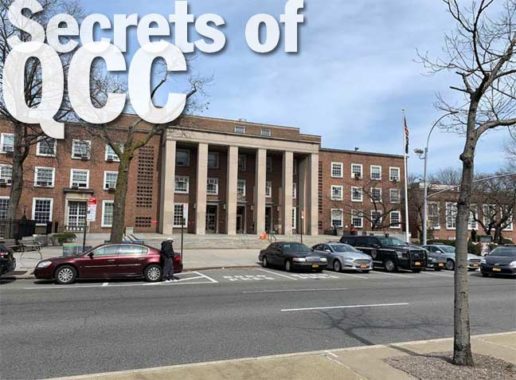

Queens Borough Hall is austere in comparison to its counterparts in the Bronx (old and new), Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Staten Island. Completed on Dec. 4, 1940 by architects William Gehron and Andrew J. Thomas, its design was the result of cost-saving during the Great Depression. Stretching for 850 feet facing Queens Boulevard, the building hosts the offices of the Queens Borough President, and various city agencies.

Prior to Kew Gardens, the Borough President’s office was in Long Island City. The name of the borough does not appear above the main entrance columns, and the two wings on either side do not have symmetric ends. The Queens Museum building is its contemporary, completed two years earlier. As it received a post-modern facelift in 2014, perhaps the same could be done with Queens Borough Hall. On the other hand, if it isn’t broke, why fix it? The legacy of its architects is functional simplicity. It does have a postmodern-style atrium in the back.

Retired Redbird subway car 9075 was adopted by Borough Hall in 2005 and used as a visitor’s center promoting Queens tourism. Lack of visitors resulted in its closing a decade later. True, there were hardly any tourists here but with newlyweds, jurors, and public workers, coming to Borough Hall, perhaps a Shake Shack or halal food establishment may have better luck inside this Redbird. I proposed the idea to Borough President Melinda Katz and have yet to hear from her. As its signature coat of red paint rusts away, I fear for the future of this Redbird.

Prior to the construction of Borough Hall and the County Courthouse, the land bound by Queens Boulevard, Union Turnpike, and Van Wyck Expressway was undeveloped, as seen in in this 1936 photo from the NYPL collection.

The location of Borough Hall in the center of Queens makes sense when looking at a map predating the county’s absorption into New York City. On this 1891 map by Joseph Rudolf Bien, we see the tripoint where the borders of the towns of Newtown, Flushing, and Jamaica meet. That spot has been known since colonial times as Head of the Vleigh, where Flushing Creek springs from the ground. Local historian Carl Ballenas and water researcher Eymud Diegel however found another source for Flushing Creek father uphill, Cow Kill Pond, on the site of today’s Hoover Playground.

B on the map represents Borough Hall, and C is the courthouse, near the tripoint of the three former town borders. From left to right, the blue arrows represent Crystal Lake, Goose Pond, and Redder’s Pond. (Hidden ponds are my specialty)

The second defining facility of the Queens civic center is the Criminal Courthouse, built in 1960 by William Gehron and Alfred Easton Poor in a modernist style that avoids ornamentation.

Unlike Borough Hall, this facility had a postmodern facelift in 1991 by architects Ehrenkrantz, Ekstut, and Kohn that have it the glass facade entrance on Queens Boulevard and the full length glass wall facing Hoover Avenue. It also received a Percent for Art piece by Japanese sculptor Sisumu Shingu titled Dialogue With the Sun, designed to intereact with the wind by spinning in all directions.

But the final piece of art that I can share before taking the elevator to the jury room is perhaps the mosaic titled Jurisprudence, an apparent blend of Art Deco with surrealism by Eugene Francis Savage (1883-1978). The elaborate mural depicts the course of justice beginning with the crime committed and the process of restitution that results in a verdict. On the left side Savage illustrates allegorical scenes for the terms Error and Transgression, along with the seven deadly sins of Vanity, Envy, Hate, Lust, Sloth, Perdition, and Avarice. To the right of the sins above the entrance to the elevator banks are Plea, Inquiry, and Evidence- the pillars of the legal process.

On the right side of the mosaic are: Correction, Exoneration, Rehabilitation, Faith, and Security. The amount of detail in this mosaic contrasts sharply with the rest of the architecture here, which is nearly as banal as the detention complex behind the courthouse. Savage’s works can be found as far afield as Washington, D.C., Indianapolis, Honolulu, Covington (Indiana), Purdue University, Yale University, and the American military cemetery in Epinal, France. He also documented the Seminole natives of south Florida.

His better-known works in NYC are the Bailey Fountain at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn, and at the Butler Library at Columbia University. But the greatest collection of courthouse art in the city must be the New York County Courthouse. Its crown jewel, Attilio Pusterla’s Law Through the Ages, known to many as the Sistine Chapel of NYC.

Savage’s Jurisprudence mosaic does not appear on the DCAS website, nor anywhere else online, to my surprise. That’s why we have Forgotten-NY.

If you wish to see more examples of public art in a Queens courthouse, Kevin Walsh has a 2015 essay on the Queens Supreme Court in Jamaica. On a related note, when I’m not writing about hidden urban waterways and city history, I teach American Art history at Touro College.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/1/19